In November 1938 Picture Post devoted 11 pages to pictures of a Loyalist attack on Insurgent troops outside Barcelona. They described one, showing men sheltering from falling shells, as ‘the most amazing war picture ever taken’. The caption to the full-page portrait of the photographer read ‘The Greatest War-Photographer in the World: Robert Capa’. Life also ran the story and described how Capa had crossed the river Segre with the troops the night before the action.

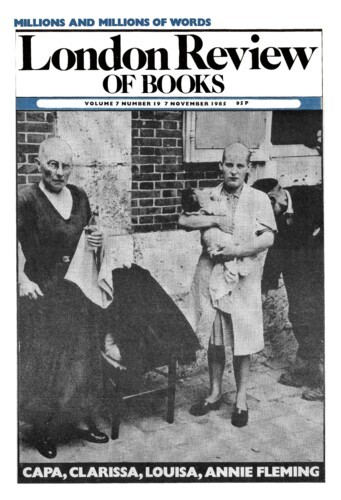

During the next few years Capa filed pictures of war and its aftermath from China, Normandy, Sicily and Africa. His pictures of a falling Loyalist, of the D-Day landing at Omaha Beach, of a collaborator, her head shaved and a baby in her arms, being mocked by a French crowd, of a tired bomber pilot, a dead machine-gunner, and the crowds lining the streets of liberated Paris, put him in the small class of photographers whose images of war, reproduced again and again, are known to almost everyone. The D-Day landings and the Liberation of Paris bring Capa’s pictures to mind as surely as the massacre at Scios suggests Delacroix, or Guernica Picasso.

Photographing war, death and human misery is a messy, dangerous business. Capa had an innate sense of what made a striking image, but had he not also been tough, opportunistic and charming he would not have got the pictures which made his reputation. If a little embroidery made the meaning of a story clearer, or more amusing, Capa would sometimes embroider. Richard Whelan, reasonably enough, is not interested in giving Capa good and bad marks for his conduct, but begs almost all the questions about the morality of photographing sadness, sickness and death when he writes of Capa’s most famous photograph – ostensibly of a Spanish Loyalist at the moment he is hit by a bullet – that ‘to insist upon knowing whether the photograph shows a man at the moment he has been hit by a bullet is both morbid and trivialising, for the picture’s greatness ultimately lies in its symbolic implications, not in its literal accuracy as a report on the death of a particular man.’

Even Whelan would doubtless draw the line somewhere – at faked pictures, rich in ‘symbolic implications’, of Hiroshima or Belsen, perhaps. But underlying his attitude is the realisation that ‘great’ war photographs are valued for their symbolic content, and that to identify the accidents or manipulations which made them more telling is not necessarily to discredit them. Inspecting contact sheets and checking out dates and places proves inconsistencies between what some of Capa’s pictures show and what the captions they carried when they were first published said they showed. The most famous case is that of the dying Spanish soldier, but there are others: what happened one day is credited to a different day, interned Loyalists are not crossing a border but moving from one camp to another, Capa had not, as the Life report claimed, crossed the Segre with the troops at night (he was at a party with Hemingway and Malraux in Barcelona) but arrived at the front the next day.

All this does not seriously undermine Capa’s reputation as a war correspondent: many of his pictures could only have been taken by someone in at least as much danger as the people he photographed, and he certainly tried to follow his own precept – ‘if the picture is no good you are not close enough.’ But Whelan’s book does make you re-run the great World War Two pictures in your head, and wonder what they tell you about that war.

Capa had something of the amoral charm of Thomas Mann’s Felix Krull: ‘It is a favourite theory of mine,’ Krull says, ‘that every deception which fails to have a higher truth at its roots and is simply a barefaced lie is by that very fact so grossly palpable that nobody can fail to see through it. Only one kind of lie has a chance of being effective: that which in no way deserves to be called a deceit, but is the product of a lively imagination which has not yet entered wholly into the realm of the actual.’ Things ‘which had not yet entered wholly into the realm of the actual’ were, in art and life, part of Capa’s style.

Whelan demythologises Capa without being sour. John Hersey wrote that ‘despite all his inventions and postures Capa has somewhere at his centre a reality. This is his talent’ – and described that talent as you might an actor’s or a gambler’s. Perhaps the wars he covered encouraged that kind of reporting. The sentimentally tough style of Capa’s pictures matches that of the prose of star reporters like Hemingway. In his autobiography Slightly out of Focus, Capa was frank about his romancing. Highlighting reality with touches of fiction is a universal game: Capa enjoyed catching others playing it, and was reckoned to have cost Taft an election with photographs showing publicity pictures being taken of the Senator hooked up to a dead sail-fish. He played it himself: ‘Robert Capa’ turns out to have been an invention. Wishing to make more money from his pictures he and his girlfriend/agent credited them to a mythical but hugely successful American photographer, Robert Capa, who insisted on three times the going rate (the resemblance to ‘Capra’ was probably no accident, and more than once Capa profited by failing to disabuse people who confused the names). André Friedmann, who took the pictures, in the end took on the persona, and when he became an American citizen he made the name official. But nature was taking the form of art well before that. ‘Capa is Hungarian, but more French than the French; stocky and swarthy, with drooping comedian’s eyes ... the life and soul of the Second Class,’ was how Isherwood saw him, China-bound, in 1938. He was only 25, but already a veteran war-photographer on his way to his second campaign.

He was born in Budapest, grew up the spoilt favourite child of a hard-working mother and charming feckless father who ran a tailoring business. The young André became involved in left-wing politics, was arrested, beaten up by the secret police, and advised to leave Hungary. He went to Berlin, and then to Paris. The description of these early years, when he was very poor (the family business was ruined in the depression) and learning to take pictures while working for a photographic agency, suggest that resourcefulness and charm were already important skills. The lessons of poverty (that you can live for a bit on sugar dissolved in water, that if you pay all your back rent in one go it will only encourage the landlord to throw you out) were added to the street wisdom of the Budapest schoolboy. In London today, the young Friedmann would be making trouble at a football match. In Budapest in the Thirties, it was political demonstrations: but even there he was more a manipulating observer than a participant. He once began chanting ‘scrap iron, scrap iron’ to see if any nonsense would be picked up as a slogan. It was.

He liked people and made them like him; his most famous pictures are of battles, but many of his best are of civilians, of the prelude or aftermath of battle rather than the action. He made people accept him – the London family, for example, who were the subject of a story he did on Britain at war, or the troops whom he followed in the European and North African campaigns. He loved pretty women, who regularly returned the compliment. The one he said he wanted to marry, Gerda Tarot, was killed in an accident while photographing the war in Spain in 1938. By the time she died their love-affair had become, on her side at least, a friendship. After her death, Capa, bending fact to the shape that suited him, said to the friends to whom he gave pictures of her that she’d been his wife. After the war, he had an affair with Ingrid Bergman – but he did not like Hollywood and neither was willing to shape their life to fit that of the other.

When the Second World War arrived he was prepared: with skills, an instinct for where the last bed, bottle, or plane out would be found and – thanks to Life, Look and the rest – a public. The pictures from the Second World War are the climax of Robert Capa: Photographs. The book begins with one of his first published pictures – of Trotsky lecturing in Copenhagen. Trotsky’s raised fist is echoed again and again – in Popular Front salutes, Fascist salutes, the salutes of soldiers leaving for the Spanish War, at the farewell ceremony for the volunteers of the International Brigade in Barcelona in 1938. In Spain he shot his first air-raids, and his first columns of refugees. There is an amazing picture from China of a platoon of deep-breathing military, hands on hips and noses in the air like a squadron of plump principal boys, and one of an improbably balletic Gary Cooper crossing a stream on a log, fishing-rod in hand. In Mexico, in 1940, he photographed a man shot in an election-day skirmish – heads peer in round the frame as though it was an open door. Then, in 1942, the war pictures begin: North Africa, Sicily, the D-Day landings, the Liberation of France, the invasion of Germany and the Occupation of Berlin. Peace comes – Picasso, Ingrid Bergman, and a magical picture of diners at the Tour d‘Argent watching Bastille Day fireworks. And there is the last black-framed, boring picture which happens to include the Indochinese embankment on which the land-mine which would kill him was waiting.

His war pictures suited the needs and matched the perceptions of the agencies, military and commercial, who were his sponsors. Not many bodies, rather a lot of drama, many welcoming crowds, a few defeated enemy. The tragedies were not those of meaningless waste but of heroism. The final effect, when you contrast it with that produced by the pictures of the Korean and Indochinese wars, is optimistic. When the war was won in Europe Capa talked of having a card printed reading ‘Robert Capa, War Photographer, Unemployed’. Certainly no other employment ever suited him so well. He tried movies, did a number of travel pieces for Holiday magazine, and in the end (and fatally) a little more war work. He was filling in for a Life photographer when he was killed in 1954.

His two monuments were his own pictures and Magnum, the photographic agency which he helped found after the war. Picture magazines can no longer be the first out with images of disasters, wars or even weddings. When Life was revived, its market was amateur photographers. Pictures with a message or purpose are corraled in specialist magazines, on sport or travel or fashion or food or wild life. The news magazines use small pictures in colour. The picture story, where the medium is not the message, where the content is more important than the style, is pretty well dead. But the style and standards of the photographers who worked (and work) for Magnum affected at least three decades of photo-journalists. At their best, they produced pictures which still seem important, visually and socially. The style has also carried with it a slightly sanctimonious, ill-focused belief in the ability of photographs to tell the truth in a uniquely unbiased way, and even to change the world. This belief has not stood up well, and writers about photography now insist that pictures tell as much about the photographer as the subject. This useful biography of Capa contributes to the demythologising process and shows once again that simple truths embodied in memorable photographs have as much to do with art and rhetoric as with evidence and history.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.