Red on Red: The inauguration of the People’s Republic of China

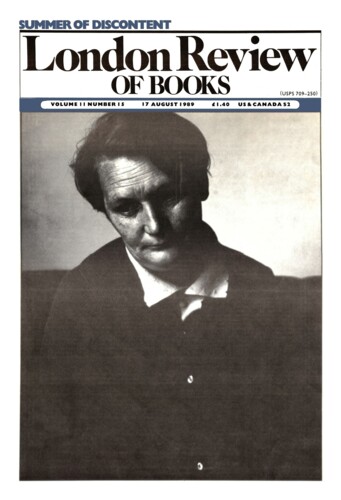

William Empson, 30 September 1999

2 October 1949. Yesterday we were busy with Jacob’s birthday till about five (or rather Hetta and Walter were and I was hanging about): then Kidd and his wife turned up and we all set out to look at the celebration of the new Government and capital. There was supposed to be a difficulty about getting sanluerhs, but we did and Hetta and I at once got separated from the others because our drivers went left by Coal Hill instead of right. Columns of soldiers were marching east and we didn’t see how to turn south through them towards Tien An Men. So we walked westwards to the pailou beside Pai Hai, getting rid of sanluerhs. The north gate was finely got up. I did not expect to be more than bored, but found myself extremely moved almost at once. You may believe that what is being celebrated will turn out a delusion, but history is full of gloomy afterthoughts. Here you have celebrated a victory of revolt against tyrants, supported by the countryside alone, practically with their bare hands, against a government drawing on the full terrors of modern equipment with medieval or fascist police methods into the bargain. If anything in history is impressive you are bound to feel that is. The troops looked very brown and sturdy, and had probably done some fighting (conceivably on the other side no doubt); some looked dolts, perhaps the majority, but none had an air of successful brutality, and the young with an air of simple goodness could regularly be picked up – the face that first struck me as so unlike Peiping when I crossed the lines to go to Tsing-Hua. They were singing, off and on, those extremely impressive marching songs. They were fully and elaborately equipped, some platoons with fixed bayonets, some carrying e.g. machine guns spread-eagled between four, who would be relieved occasionally by neighbours. I could not see if it had American lettering on, but the reflection that the equipment must all have been captured did seem to me enormously impressive. Only a few idlers were looking at them.