2 October 1949. Yesterday we were busy with Jacob’s birthday till about five (or rather Hetta and Walter were and I was hanging about): then Kidd and his wife turned up and we all set out to look at the celebration of the new Government and capital. There was supposed to be a difficulty about getting sanluerhs, but we did and Hetta and I at once got separated from the others because our drivers went left by Coal Hill instead of right. Columns of soldiers were marching east and we didn’t see how to turn south through them towards Tien An Men. So we walked westwards to the pailou beside Pai Hai, getting rid of sanluerhs. The north gate was finely got up. I did not expect to be more than bored, but found myself extremely moved almost at once. You may believe that what is being celebrated will turn out a delusion, but history is full of gloomy afterthoughts. Here you have celebrated a victory of revolt against tyrants, supported by the countryside alone, practically with their bare hands, against a government drawing on the full terrors of modern equipment with medieval or fascist police methods into the bargain. If anything in history is impressive you are bound to feel that is. The troops looked very brown and sturdy, and had probably done some fighting (conceivably on the other side no doubt); some looked dolts, perhaps the majority, but none had an air of successful brutality, and the young with an air of simple goodness could regularly be picked up – the face that first struck me as so unlike Peiping when I crossed the lines to go to Tsing-Hua. They were singing, off and on, those extremely impressive marching songs. They were fully and elaborately equipped, some platoons with fixed bayonets, some carrying e.g. machine guns spread-eagled between four, who would be relieved occasionally by neighbours. I could not see if it had American lettering on, but the reflection that the equipment must all have been captured did seem to me enormously impressive. Only a few idlers were looking at them.

The red flags, stars etc on the red of the palace walls (a poppy scarlet on a faintly mauve rust-red) makes a gorgeous basis always for the colour schemes of the capital, and perhaps a symbolical one; the present blank insistence that Thibet is part of China, merely because the emperors conquered it in the past, does not give the impression that one red is to be obliterated by the other. Indeed, the whole idea of a tremendous procession and display which practically no one looks at – at least with many streets closed to spectators and no arrangements for them – is very like imperial sentiment. Two lao-pai-hsing passed a remark to this effect, the sanluerh man on the way home passing the Forbidden City north gate, who said there are the King’s lanterns being used, and our cook who said it was all a waste of public money just like the emperors. However, I don’t think that is a bad thing in itself; anyway, it is a reasonable result of Communist doctrine that the people themselves are the procession – it is the ones who turn out for it that the Government is trying to impress; it does no harm to the Government (however much harm it may eventually do to the rest of the world) if the people think they are reviving the imperial glories.

After waiting a bit at the corner east of the Peihai pailou, where a lot of horses drawing light guns had started to pass, we found it was correct to cross over in the gaps (a few spectators were there, mostly children) and then took sanluerhs due south to the arch giving on the road past Tien an Men. A small crowd was peering through the three arches, and behind them handsome tanks with gun turrets were coming past in formation, two abreast I think. On the other side of the street there were more spectators, who had been allowed to spread outwards a bit from the corner, but they, too, were not allowed far along the street. This is a splendid avenue with trees and about fifty foot of clearance on both sides of the motor road, just where the procession leaves the great square. It was an ideal place to admit spectators, especially because it is separated from the main square by a massive wall with five arches, only two smaller ones not on the main road; thus two policemen could have kept the crowd out of the square (as soon as the procession occupied the road anyhow). It seemed very remarkable that this was all forbidden ground, even if so few people wanted to come on it. Of course, it is fair to say that once a big crowd had got there it would take a lot of police to clear the motor road area for tanks and cavalry; but the effect became something extremely different from the victory parade earlier in the year. There it was a matter of pushing lorries through densely crowded cheering streets, lorries full of heavily armed soldiers ready for trouble to be sure, but also a crowd that kept leaping up and pressing the hands of the soldiers.

However, the few police at our archway, soon after we arrived, began letting the crowd leak onto the great empty space and then eastward under the trees. It remained a thin crowd, or rather thick only at the point of advance, but it had made about fifty yards before the military parade was over, just before dusk; then the civilian parade followed straight on, and we were allowed to advance to the arch giving on the great square. Slowly, we leaked again through that, till when Hetta and I left we were about fifty yards into the square: this was 8.15. By that time a few soldiers and people carrying red-star lanterns had joined the spectators – presumably bits of the procession no longer on duty. No old spectators that I remember. The police were not at all rattled and handled the crowd well, on the assumption that they were an entirely trivial part of the affair, of course, needing only a few men who could apparently use their own judgment. A few people stared at us, and we avoided thrusting in the front line, but there was no anti-foreign feeling shown at all.

Going back to the tank demonstration when we first arrived, the only thing to say is that it looked very fine, kept in line tidily, and went past at a spanking pace for a long time; I don’t know how long it had been going on before we came. These were presumably all taken over in the surrenders. It did not occur to me at the time that they might well have been needed in the civil war which is still in progress; I suppose really they are a nuisance to move all that way south, eat up a lot of petrol, and are continually being supplied by surrenders on the spot. We next had about a quarter of an hour of cavalry, a long bunch of white ponies trotting in columns of fours, then browns, then piebalds, then whites, all briskly but less fast than tanks. The procession was of course starting just behind us; I do not understand how its trip round the town was arranged. Apparently the square was planned to hold 160,000 people, and a lot of trees had previously been cut down to clear the view; they had been listening to speeches relayed by microphone all day and the military parade was to go through before dusk. After the horses we had columns of marching men again (none that I saw carrying machineguns etc, so I don’t know when the ones we saw in the north of the town got through – probably there was an intermittent military parade for most of the day between speeches). The later stages of troops came through as dusk was beginning, and they came through at the double still in columns of fours, reminding one of the trotting horses. At this stage, as I remember, the fireworks began. Their impressiveness perhaps depended rather on knowing what was along the road behind the trees, the enormous calm proportions of the entry to the Forbidden City, but impressive anyway I thought they were. They were all of one type, small coloured or generally white fireballs shot up in a cluster about 300 feet high from several main centres, four at the four corners of the square, arranged so that one was going up when another was coming down. The movement up was cool and smooth, an effect of effortless power suggesting a fountain but even more the growth of a tree, and one of these ballet movements over the vast planned proportions of the Forbidden City would begin just as another was sinking onto the point of the toe. This went on steadily for an hour and a bit. We were in doubt all the time whether to stick to our positions, but felt that the drifting of the crowd argued that we were sure to get into the square eventually, as we did.

A few thousand more soldiers having been got rid of at the double, the civilians lit their lanterns and began coming after more calmly. I take it the small objects used candles and the large ones bicycle lamps. Nearly all used red paper, for stars, cubes representing the new flag, and various odd objects such as an apparent red cross on a stand which might have meant a box kite. There were also whole companies of torches, made out of sticks with some kind of rag steeped in tar at the top, we thought. There were miles of these illuminations for hours – the square, we heard later, was to be cleared at ten, and it was emptying steadily by both the north-east and the north-west gates. An interesting little economic question arises about the price of red paper; Hetta was buying some the previous day for the child’s birthday, and the price and supply were unaffected. That had been arranged with success, evidently. A new rule had come into force the previous week (long overdue) that bicycles must have lamps, and we bought them at very inflated prices on that last allowed day. However, plenty of people would have bought bicycle lamps and they could easily be borrowed for the one night. (By the way, on Friday I noticed that only about half the bicycles or sanluerhs were using lights.) I don’t know about the price of candles.

In any case, the point is that all schools and universities, and apparently all factories and trades (at any rate many were carrying illuminated symbols of their functions), had sent large delegations to this procession; few older people no doubt were represented, but a fair proportion of the younger people in the town must have been actually taking part. Of course it is they and not any spectators who are intended to be pleased. The first lot marching out did not seem particularly cheerful, indeed it seemed rather hard on the children to make them march away from the fireworks, but this kind of difficulty is inherent in a procession. At about this stage we were allowed to go forward to the arch before the square, and not long after to leak through it.

The great gate itself was a shock, as three oblong pictures which remained invisible to us had been illuminated round the border with neon electric-blue bands; the clashing light and dark reds above and below were made even more gloomy, and the beastly thing looked like a mad centre of life in an extremely Chinese or rather Taoist mode of sentiment, so no doubt most of the audience admired it very much, but nobody could call it good taste. (The daytime ornament on it has always been in good taste, I think; for that matter, the old titanic picture of Chiang Kai-shek, which disappeared two months or so before the liberation, seemed to me in excellent taste.) The area of the square in front of us was bare to the centre, covered with bits of paper so that it had been packed till the procession began. Many of the fireballs were landing still alight – one hit a man in front of us and another burning much more fiercely landed in the middle of the procession, which consisted of schoolchildren just then. They ran back from it and went gaily on. Making the fireworks dangerous to the crowd seemed an extra touch of Oriental Magnificence and will not get the Government badly thought of at all I imagine. Earlier there had been a Red Cross van moving through our arch towards the square; however, this argues that reasonable arrangements were made, and we saw no one seriously hurt.

On the great gate the marble balcony was floodlit and a line of notables there could be dimly discerned. Two rostrums with a yellow band below (the further one to be deduced from its line of electric lights only) were on either side of the marble bridges leading to the gate; floodlighting on the bridges was intermittent. The main scene was a line of red lights moving up from far away to the south towards the gate, half of it turning towards us, half the other way. An occasional band came by, and a loudspeaker sometimes played rather irrelevant tunes, but there was not much singing. However, the thing was still warming up. I have not yet praised the banners of the new Chinese flag, red with a star and a variable extra on it, which would lead a new detachment of the military procession; they seemed of extremely soft material glowing by its own light and were a good thirty feet high, so that they bobbed away with a kind of independent jellyfish motion. We now saw six or eight of these clumped together advancing southward slowly, a bit like ships, over the floodlight marble bridge. The shade of red has rather the same effect as the Catholic Sacred Heart; it looks like entrails; it has some weird ‘intimate’, emotive effect, and in this tremendous setting it gave at once the feeling that is described as unforgettable – I still think I am very unlikely to forget it. Of course we were seeing the white decorated floodlit bridge end on, and could look at it along the water that it crosses; only a few rather insistent loafers were in this position, much the finest for the dramatic effect, and the odd thing about the whole affair, as it struck me, was that the best bits were planned to exist in themselves, not for anyone to look at.

We kept thinking that the square must empty at last, and that we would like to be in at the death. At its most crowded, with all three arches on the motor road in use, thirty or forty people carrying red lanterns could go by abreast. Sometimes there would be pauses, sometimes long groups (usually schoolchildren) would be sent by at the double. Gradually, the loudspeaker took to shouting slogans, echoed loudly by the patch of procession which would pause at the gate to receive them: the invisible notables behind the glow apparently uttered brief sentiments rapturously received; cries for Mao Tse-tung were very frequent, and all we could make sense of, but anyway spontaneous singing began again in the procession, so that at last the good music of the revolutionary songs began to replace the odd gaieties of the microphone; the thing was warming up; the great glaring central octopus itself was becoming vocal, as the square itself seemed more and more bound to be empty. At last the trip across the marble bridge to the central throne became increasingly frequent; not only a few thirty-foot standards but a solid flood of red-star small lanterns (with ears seen from the side, indeed when carried in mass by nearly [sic] girl children very like tulips, but on the distant bridge a glowing lava) lifted and lowered in rhythm to an increasing noise of singing, and moving away from us on the north side of the bridge as if to form a solid block waiting to adulate the throne. Our gate was no longer in use, but there was no sign of the end of the thing; the red flow from the far south increased and was apparently now all going over the now permanently floodlit bridge. There was no prospect of getting to the centre of the square to see the decorations front face within reasonable time, and we set off home about 8.15. On the way, as we went to the arch giving northwards, a red procession appeared backward on its way back to the square. The side running north was more or less deserted, except for an ex-platoon of the procession returning with its lamps to the door of its institution. The few sanluerhs about did not much want to travel, but we got a couple which did not make unreasonable demands. The northern road had a group of schoolboys dancing the yangka and a long line of smaller ones who seemed to have got detached, perhaps on their way home. I was glad to have seen it without Brown and Kidd, whose easy enthusiasm always chills me a good deal. Brown today reports highly elaborate yangka dancing in progress and scattered singing; the yangka badly needs a more elaborate technique, but no doubt that will be learned more generally in time. It really seems a very successful affair.

Later, 2 October. I have been to the Tien An Men again to reconsider the great problem of whether it is in bad taste. From the side the great gold ornaments of the gable or pediment pull it round a great deal in daylight: it looks gorgeous and bulging in a massive central manner, and it is appropriate enough. From the front, one realises that the central portrait of Mao is nearly all blue, dark blue uniform and light blue sky, a striking contrast to the reds except for the mauve red of the two side panels with writing. There were the areas surrounded with neon tubes, and if we had seen the thing front face at night I daresay it would have given the hue an unearthly glory, thus at least looking a legitimate effect. I was wrong in saying before that the palace walls are a mauve red: it is a chocolate rust-red; it only matches mauve, and the mauve panels are laid on it. Above we have the deep, hot, constipated Victorian crimson of the row of four-foot pompons in the balcony and the band over them. On top, between layers of the yellow-gold roof, is a firm, rather deep scarlet band. Outside, in six great flags on the wall, is the thrilling spiritual, transparent blood-red of the religion. Also, the stands in front which hold the floodlights are a bright brisk, rather salmonish gay pink. In its tremendously overwrought way I think it must be called successful.

Then I went and looked at it through the arch in the far south, with a slight puzzle from the police because a bicycle must not come through, and it turned out that the thing looks almost unaltered except for one or two bits of decoration. The sheer size of wall and roof is all that stands out, so that this apparent overdecoration is necessary if the whole square is to be affected by the thing. From the side far off, as at the north of the British Legation street, it looks a gay little teacake and apparently has some mauve sheeting along the balcony at the side. The coolness of the richly ornamented object when left alone is I suppose when [undecipherable] tends to shock one when it is adapted to the modern world.

I failed to say before how very Alice in Wonderland these huge swaying red figures are, in their crowd, drifting about in various directions with an air of carrying out unknown but pedantic rules.

William Empson, with his wife and two young sons, lived from 1947 to 1952 in Peking, where his teaching post at the Peking National University was subsidised by the British Council. The Empsons remained there throughout the civil war between the Nationalists and Communists, enduring the six-week siege of the city from December 1948 to January 1949.

After years of occupation and neglect, the fabric of the city was a mixture of downtrodden imperial splendour and indigent modern bustle. More than two million people lived within the 25-mile oblong perimeter of its crenellated walls, which were 40 feet high and ‘broader than Fifth Avenue’ (as an American correspondent remarked). Large, regular thoroughfares drove from one to another of the two-storeyed gate-towers, east and west, north and south, boxing the compass of the three constituent sectors of the city: the Imperial City, the Tartar City and the Chinese City. The intersections were marked by glossy triumphal arches, called p’ailou, of painted wood surmounted by high banks of coloured tiles. Within the symmetrical pattern outlined by its walls and highways, alleys of trodden mud created an insoluble jigsaw puzzle between high and windowless walls that screened off courtyard homes, small businesses and workshops. At the heart of the whole stood the Forbidden City, the Imperial Palace of the Ming and Ching dynasties (since 1925, the Palace Museum), with its walls of faded purplish pink topped by glazed imperial yellow tiles. On Saturday, 1 October 1949, Mao Zedong and his Party leaders filled the nine bays of the terrace beneath the red and gold gate-tower in order to inaugurate the People’s Republic of China.

Empson did not keep a journal, but he felt this grand historical event needed to be marked by jotting down his impressions of the ceremonial. His account was discovered among the personal effects of Hetta Empson after her death in December 1996, and is published here for the first time. Walter Brown and David Kidd were two young American teachers. Sanluerhs were pedicabs; Pai Hai is a lake to the west of the Forbidden City; lao-pai-hsing – literally, ‘Old One Hundred Names’ – means ‘ordinary people’

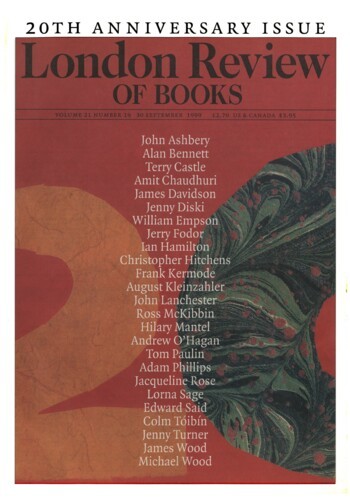

John Haffenden

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.