Salman Rushdie

Salman Rushdie wrote half a dozen pieces for the LRB in the paper’s early years, including reviews of Calvino and García Márquez, a short story (‘The Prophet’s Hair’) and a piece reflecting on ‘Imaginary Homelands’, the Bombay of his childhood and the writing of Midnight’s Children.

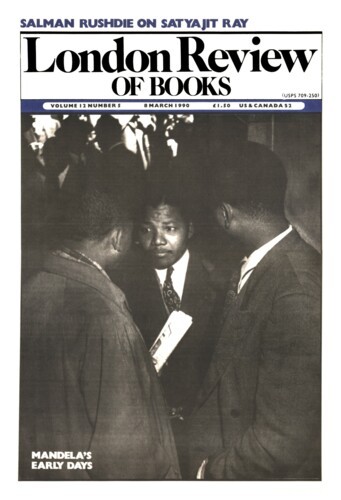

Homage to Satyajit Ray

Salman Rushdie, 8 March 1990

‘I can never forget the excitement in my mind after seeing it,’ Akira Kurosawa said about Satyajit Ray’s first film, Pather Panchali (The Song of the Little Road), and it’s true: this movie, made for next to nothing, mostly with untrained actors, by a director who was learning (and making up) the rules as he went along, is a work of such lyrical and emotional force that it becomes, for its audiences, as potent as their own most deeply personal memories. To this day, the briefest snatch of Ravi Shankar’s wonderful theme music brings back a flood of feeling, and a crowd of images: the single eye of the little Apu, seen at the moment of waking, full of mischief and life; the insects dancing on the surface of the pond, prefiguring the coming monsoon rains; and above all the immortal scene, one of the most tragic in all cinema, in which Harihar the peasant comes home to the village from the city, bringing presents for his children, not knowing that his daughter has died in his absence. When he shows his wife, Sarbajaya, the sari he has brought for the dead girl, she begins to weep; and now he understands, and cries out too; but – and this is the stroke of genius – their voices are replaced by the high, high music of a single tarshehnai, a sound like a scream of the soul.’

Kundera and Kitsch

7 June 1984

Imaginary Homelands

Salman Rushdie, 7 October 1982

An old photograph in a cheap frame hangs on a wall of the room where I work. It’s a picture, dating from 1946, of a house into which, at the time of its taking, I had not yet been born. The house is rather peculiar – a three-storied gabled affair with tiled roofs and round towers in two corners, each wearing a pointy tile hat. ‘The past is a foreign country,’ goes the famous opening sentence of L.P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between, ‘they do things differently there.’ But the photograph tells me to invert this idea: it reminds me that it’s my present that is foreign, and that the past is home, albeit a lost home in a lost city in the mists of lost time.

Angel Gabriel

Salman Rushdie, 16 September 1982

We had suspected for a long time that the man Gabriel was capable of miracles, because for many years he had talked too much about angels for someone who had no wings, so that when the miracle of the printing presses occurred we nodded our heads knowingly, but of course the foreknowledge of his sorcery did not release us from its power, and under the spell of that nostalgic witchcraft we arose from our wooden benches and garden swings and ran without once drawing breath to the place where the demented printing presses were breeding books faster than fruit-flies, and the books leapt into our hands without our even having to stretch out our arms, the flood of books spilled out of the print room and knocked down the first arrivals at the presses, who succumbed deliriously to that terrible deluge of narrative as it covered the streets and the sidewalks and rose lap-high in the ground-floor rooms of all the houses for miles around, so that there was no one who could escape from that story, if you were blind or shut your eyes it did you no good because there were always voices reading aloud within earshot, we had all been ravished like willing virgins by that tale, which had the quality of convincing each reader that it was his personal autobiography; and then the book filled up our country and headed out to sea, and we understood in the insanity of our possession that the phenomenon would not cease until the entire surface of the globe had been covered, until seas, mountains, underground railways and deserts had been completely clogged up by the endless copies emerging from the bewitched printing press, with the exception, as Melquiades the Gypsy told us, of a single northern country called Britain whose inhabitants had long ago become immune to the book disease, no matter how virulent the strain …

Pieces about Salman Rushdie in the LRB

The Profusion Effect: Salman Rushdie’s ‘Quichotte’

Michael Wood, 12 September 2019

‘One can feel that there is always a camera left out of the picture,’ Stanley Cavell writes in The World Viewed. He is writing of a literal movie camera, but he suggests a...

Closely Observed Trains on a Sea Coast in Bohemia: Rushdie’s Latest

Christopher Tayler, 16 November 2017

Some people don’t like the idea that they may be living in a metropolitan bubble, but René Unterlinden, the narrator of Salman Rushdie’s latest book, has been raised to call...

Imagine his dismay: Salman Rushdie

Carlos Fraenkel, 18 February 2016

Salman Rushdie’s latest novel is a version of The Arabian Nights – two years, eight months and 28 nights adds up to 1001 of them. But it’s updated in every way. The climax,...

The Audience Throws Vegetables: Salman Rushdie

Colin Burrow, 8 May 2008

Even serious and persistent readers often say they can’t finish Salman Rushdie’s novels. His unfinishability has some obvious causes. Wearyingly encrusted description is the natural...

Flame-Broiled Whopper: Salman Rushdie

Theo Tait, 6 October 2005

With time and overuse, artistic style degenerates into mannerism. This is especially true of magic realism. Following the success of Gabriel García Márquez, a flood of...

The First Bacchante: ‘The Ground Beneath Her Feet’

Lorna Sage, 29 April 1999

‘Where the plates of different realities met, there were shudders and rifts. Chasms opened. A man could lose his life.’ This seismic imagery is, in Salman Rushdie’s The Ground beneath Her Feet, the...

Shenanigans

Michael Wood, 7 September 1995

The Moor’s last sigh is several things, both inside and outside Salman Rushdie’s sprawling new novel. It is the defeated farewell of the last Moorish ruler in Spain, the Sultan...

Deadly Fetishes

Terry Eagleton, 6 October 1994

Magic realism is usually thought of as a Third World genre, appropriate to a place where the supernatural is still taken seriously, where fable and folk tale still flourish and where fantasy can...

Toto the Villain

Robert Tashman, 9 July 1992

A good piece of writing on film, produced by a major literary figure, is as rare as a successful film adaptation of a major literary work. The fear and condescension felt towards the medium by...

Embracing Islam

Patrick Parrinder, 4 April 1991

‘Our lives teach us who we are,’ Salman Rushdie observed in one of three widely-read and somewhat contradictory statements of faith that he published last year. These are now...

Saving the Streams of Story

Frank Kermode, 27 September 1990

No doubt it would be possible to apply to this exercise in magic irrealism the terminology of V. Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale, by way of demonstrating that Salman Rushdie’s...

Let’s get the hell out of here

Patrick Parrinder, 29 September 1988

Here, in these three novels, are three representations of the state of the art. In The Satanic Verses the narrator, who may or may not be the Devil, confides that ‘what follows is tragedy....

Irangate

Edward Said, 7 May 1987

The ostensible reason for the enormous concern in America over the Irangate affair has been the question of whether the President and his National Security Council, together with the CIA and...

Tristram Rushdie

Pat Rogers, 15 September 1983

Four titles, and an abstract noun apiece – well, Melvyn Bragg has two, but it’s the well-known coupling as in (exactly as in, that’s rather the trouble) a fight for...

Experiments with Truth

Robert Taubman, 7 May 1981

Bent to the ground in the gesture of prayer, one morning in Kashmir in 1915, Aadam Aziz accidentally bumps his nose – and gives up prayer for ever. This event ‘made a hole in him, a...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.