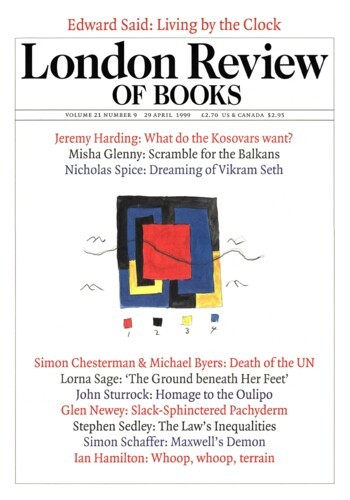

The philosopher Plotinus was such a good Idealist that he refused to have a portrait done – why peddle an image of an image? – and argued that the true meaning of the myth of Narcissus was that the poor boy didn’t love himself enough. If Narcissus had recognised whose the reflection in the water was, he’d have lived and grown and changed himself, instead of being the helpless subject of a pretty tale of metamorphosis. Salman Rushdie’s new novel is full of such Neoplatonic jokes (though this isn’t one of them). The Ground beneath Her Feet is vertiginous, perilous, on the edge, because it’s all about pushing beyond the author’s Other-love, and the techniques he has so far perfected for dissolving ‘I’ into ‘we’. Here he is embracing what his enemies have always called his arrogance. He is taking things further, to that excess whose road leads to the palace of wisdom.

It’s a winding road, though, with lots of digressions on the way. This is a novel crammed to bursting with allusions to mythology, particularly the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, she gone before into the underworld, he trying to win her back with music. They are the hero and heroine of a plot about the history of imaginative life:

In the beginning was the tribe ... then for a little while we broke away, we got names and individuality and privacy and big ideas, and that started a wider fracturing ... and it looks like it’s scared us so profoundly ... that at top speed we’re rushing back into our skins and war-paint, Post-Modern into pre-modern, back to the future.

Mythology is the idiom of the times, the language of pre and post-fracture. The novel’s immortals, its Orpheus and Eurydice, are idols of the music business: Ormus Cama, whose Parsi father Sir Darius is obsessed by comparative mythology that draws together East and West, and Vina Aspara, half-Greek-American and half-Indian. They are both vessels for the spirit of our age because they are rendered rootless early on by childhood tragedy. That’s why people loved Vina, we’re told, ‘for making herself the exaggerated avatar of their own jumbled selves ... The girl can’t help it, that’s what her position came down to.’ She’s a chimerical mixture of Madonna and (in death) Princess Diana, with other bits added on (a sting in the tail from Germaine Greer); Ormus has a dead twin brother who sings Western hits into his ear long before they burst on the rest of the world – but Ormus can never quite make out the words. When he first hears ‘Heartbreak Hotel’, which he’s been humming for more than two years, he’s furious with the American ‘thief’ of his inspiration, and as time goes on his private music of the spheres (78 rpm) teases him more and more cruelly: ‘The ganga, my friend, is growing in the tin’ has been haunting him, and ‘sure enough ... one thousand and one nights later, “Blowin’ in the Wind” hit the airwaves.’

Ormus and Vina live in a world that’s part India, part America, where the processes of mythification are far enough advanced to canonise ‘science fiction by Kilgore Trout ... The poetry of John Shade ... The one and only Don Quixote by the immortal Pierre Menard.’ It’s a bit reminiscent of the hybrid Russian-American world Nabokov invented for Ada. Here, John Kennedy wasn’t shot in Dallas but years later, along with his President-brother Bobby, by a magically bouncing Palestinian bullet, and the British Labour Government sent troops to Vietnam (which is called Indochina). Gradually the game of getting it just wrong reveals itself as a way of satirising the contradiction and double-vision we (ordinarily) take for granted. When Ormus finally makes it to America (you’re an American, says Vina, you always were), ‘It is evident from the daily newspapers that the world beyond the frontiers of the United States (except for Indochina) has practically ceased to exist. The rest of the planet is perceived as essentially fictional.’ And for that matter, ‘a kind of India happens everywhere, that’s the truth too ... There are beggars now on London streets.’ Ormus and Vina’s double act – a rock opera on stage, a soap opera off – suits this brave new world.

By comparison with the state of chronic, euphoric uncertainty (‘The uncertainty of the modern. The ground shivers, and we shake’) the India Ormus grew up in was marvellously real and solid. Bombay seemed the capital city of hybridity: ‘Good communal relations and good solid ground we boasted. No fault lines under our town.’ But that diversity, too, has proved an illusion, has been earthquaked and developed and divided. Rushdie’s tone about all this is a strange mixture of regret and revelation. Can it be that one’s very image of rootlessness was a secret refuge from change? An imaginary homeland? Apparently so. Having left Bombay behind, you have to leave the displaced person who measured himself against it too. Time to change. In earlier Rushdie novels Ormus would have been the book’s ‘medium’, the very type of the writer: ‘There are too many people inside Ormus, a whole band is gathered within his frontiers, playing different instruments, creating different music, and he hasn’t yet discovered how to bring them under control.’ But here Ormus, although certainly a genius, is at the same time doomed to mythic finality. We’re moving on, taking leave of ‘impure old Bombay’ for the nth time, but in a new spirit: ‘I am writing here about the end of something ... I am trying to say goodbye, goodbye again.’ And this ‘I’ doesn’t belong to Ormus himself, but to the novel’s narrator, who is a new kind of character for Rushdie, not the spokesperson for all the ‘others’, but a more ordinary – and thus, in this context, extraordinary – ‘I’.

He is called Rai, and he’s a photographer, the only child of loving, hopeful, sceptical, humorous parents whose break-up symbolises the failure of Bombay to resist the fissile pressures of the age. And he’s the book’s Narcissus, the one who discovers the uses of mirrors, and speaks in an aphoristic style that marks him out as the ironic survivor, who chronicles the others’ more (or less) than human fates. ‘As we retreat from religion ... there are bound to be withdrawal symptoms,’ he remarks early on. And he is sometimes given an elevated, archaic-sounding poetry to speak, like this: ‘Among the great struggles of man ... there is also this mighty conflict between the fantasy of Home and the fantasy of Away, the dream of roots and the miracle of the journey.’ But he’s also allowed some splendidly vituperative lines, as in his attack on the misuses of the word ‘culture’ as a weapon. What is it but a smear of bacilli on a slide? ‘Like slaves voting for slavery or brains for lobotomy, we kneel down before the god of all moronic micro-organisms and pray to be homogenised or killed or engineered.’ Rai is not ‘objective’, not above or outside the world of ‘mythologisation, regurgitation, falsification and denigration’. He is Ormus’s adoring friend, and Vina’s besotted secret lover. And before he follows them to England and America, he goes on an assignment in rural India that pays lavish tribute to the dream of roots: ‘The size of the countryside, its stark unsentimental lines, its obduracy: these things did me good ... Politics painted on passing walls. Tea stalls, monkeys, camels, performing bears on a leash. A man who pressed your trousers while you waited. Ochre smoke from factory chimneys. Accidents. Bed On Roof Rs 2/=. Prostitutes. The omnipresence of gods.’ Word-play and rhyme (walls and stalls, ochre smoke) are everywhere. And the whole adventure is based on a kind of pun: Rai is being sent to expose a monster fraud – the Great Goat Scam – which turns to tragedy, a word based on the Greek for ‘goat-song’. The country is part of the con-trick. The moral Rai draws from his excursion is that far from being ‘solid, immutable, tangible’, reality is ever-shifting: ‘Where the plates of different realities met, there were shudders and rifts. Chasms opened. A man could lose his life.’ This seismic imagery is his, and the book’s, most important metaphor for the universality of change, and one of the title’s main meanings. Both Ormus and Rai adore Vina, but the ground beneath her feet opens up and swallows her. And then Ormus goes after her. They are eaten up by the violent mythologies of the times, myths they themselves fed.

Rai lives to tell their tale, and to put the case for imagination as opposed to vision. ‘The god of the imagination,’ he declares, ‘is the imagination. The law of the imagination is whatever works.’ The novel is, in the old sense, a Defence of Poetry – like Sir Philip Sidney’s in the Renaissance, and Shelley’s in the early 19th century. And like theirs, it is premised on fiction’s paradoxical truth. In the first book he published after the fatwa, Haroun and the Sea of Stories, Rushdie echoed Sidney’s famous riposte to those who accused the poets of being liars. Those who purport to tell the truth (historians, for instance) can hardly avoid getting it wrong, Sidney said, whereas the poet ‘nothing affirmeth and therefore never lieth’ – he barefacedly makes it up as he goes along. Rushdie’s version went like this: ‘Nobody ever believed anything a politician said, even though they pretended as hard as they could that they were telling the truth ... But everyone had complete faith in Rashid, because he always admitted that everything he told them was completely untrue and made up out of his own head.’ It’s often said (of both Sidney and Rushdie) that this means fiction is a form of play, fabulation for its own sake. But when Sidney goes on to tell us that one of his favourite ‘poems’ is More’s Utopia, it’s clear that for him fictions have designs on us, and that their modesty in the matter of literal truth is more than made up for by their speculative ambitions. Shelley’s Defence makes the same point when it ends grandly by calling poets ‘the unacknowledged legislators of the world’. Rai echoes these unapologetic defenders of poetry when he says: ‘in our hearts we believe – we know – that our images are capable of being the equals of their subject. Our creations can go the distance with Creation; more than that, our imagining – our imagemaking – is an indispensable part of the great work of making real.’

But unlike Rai, Orpheus-Ormus and Vina-Eurydice are mystics of a last-days sort, they mistake the meaning of their own performance, particularly Vina, ‘who took books by Mary Daly and Enid Blyton with her when she went on tour’, who believes in pretty well anything that’s on offer, and who loves America because

You get to be an American just by wanting ... However you get through your day in New York, then that’s a New York kind of day, and if you’re a Bombay singer singing the Bombay bop or a voodoo cab driver with zombies on the brain, or a bomber from Montana or an Islamist beardo from Queens, then whatever’s going through your head, then that’s a New York day.

Vina is portrayed as irresistible, absurd and ultimately dangerous. Forget Eurydice, Vina is ‘the first bacchante’, a New Age primitivist, she’ll be the death of her husband Orpheus. Professor Vina, as Rai calls her, can improvise a monologue on almost any topic, and in the end her rhetoric leads to a return to tribal consciousness, ‘the battle lines, the corrals, the stockades, the pales ... the junk, the booze, the fifty-year-old ten-year-olds, the blood dimm’d tide, the slouching towards Bethlehem ... the dead, the dead’. It’s his word against hers, against theirs. He draws a difficult distinction between myths and fictions, rather as Frank Kermode did in The Sense of an Ending. A myth you act out, a fiction you believe in knowing it to be a fiction. Kermode liked to quote Wallace Stevens, the aphoristic Stevens of Opus Posthumous, and Rushdie’s Rai sounds rather like Stevens too – ‘our love of metaphor is pre-religious ... Religion came and imprisoned the angels in aspic.’ Or again: ‘When we stop believing in the gods we can start believing in their stories ... the willing, disbelieving belief of the reader in the well-told tale.’

It’s clear – this is why The Ground beneath Her Feet is such a strange and disorienting book – that belief and unbelief are in our era twins, according to this narrator and his author. The writing confounds seduction and scepticism. ‘In a time of constant transformation, beatitude is the joy that comes with belief, with certainty,’ and it’s hard to resist. ‘These are not secular times.’ Once a writer like Apuleius, in The Golden Ass, could make ‘an easy separation between the realms of fancy and of fact’, but a writer who wants to follow in his jokey, mock-magical footsteps now will have a harder time. Presumably this is why Rai loves Vina despite seeing through her, he can’t quite bear to draw the line. And Ormus he lets go with huge reluctance: ‘He was a musical sorcerer whose melodies could make the city streets begin to dance and high buildings sway to their rhythm, a golden troubadour the jouncy poetry of whose lyrics could unlock the very gates of Hell.’ This Orphic power faces both ways, towards the illusionist magic of performance and the bad faith of faith. Early on in the novel, Rai quotes from the libretto for Gluck’s Orpheus, which gives the story a happy ending – ‘E quel sospetto/Che il cor tormenta/Al fin diventa/Felicità’ and explains that ‘the tormented heart doesn’t just find happiness, okay: it becomes happiness.’ But he’s mistranslating, I think. It’s the ‘sospetto’ that tortures the heart that turns to happiness. His version reveals his eagerness for a miracle. Still, it’s a trick a lot of Orphic lyrics pull – like the one from the play of Henry VIII that used to be attributed to Shakespeare, where the first two lines make Orpheus into a god (‘Orpheus with his lute made trees/And the mountain tops that freeze’) and the third demotes him, by completing the grammar: ‘Bow themselves when he did sing.’ A little exercise in illusion – it doesn’t take all the artist’s powers away, just makes them more like conjuring tricks.

Before he turns into a mythic hero, Ormus thinks that ‘the solutions to the problems of art are always technical. Meaning is technical. So is heart.’ The novel bears out this conviction, not least in the way its structure defies the climactic-apocalyptic mode. It starts with an ending, its middle is made up of beginnings (some of them false) and the ending finds Rai in the middle of his life, with a ready-made family. The characterisation, too, with even the three main figures in unstable focus, sometimes hyper-real, sometimes near-transparent emblems and allegories, is designed for ‘disbelieving belief’. The ‘great work of making real’ – ironically enough – eats away at realism. Some while back, the (real-life) Indian-American literary theorist Gayatri Spivak, writing on The Satanic Verses, pointed out how effectively Rushdie incarnated contemporary ideas of anti-authoritarian storytelling – ‘the writer-as-performer’. Even so, she went on to say, ‘fabricating decentred subjects as the sign of the times is not necessarily these times decentring the subject’. In The Ground beneath Her Feet he is saying: yes it is, or can be, you can be a fictionist and a deconstructionist at once, and make the novel an ‘anatomy’. Having become himself a representative figure – the emblem of literature’s freedoms – he is turning the role inside out, calling his own technique into question, finding a new style for uncertainty, saying goodbye again. The effect is exhilarating, hard-to-take, heterodox, critical-creative with the stress on the critical: a fable for now.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.