Diary: London to Canberra

Karl Miller, 25 June 1987

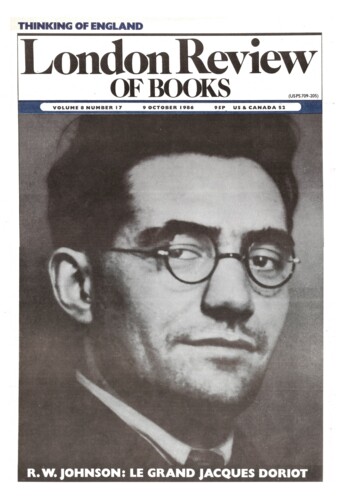

Roy Jenkins believes this to have been an insular election: it has also had more than its share of the infantilism of show business, and was one of the foulest and most name-calling for a long time. Government will now resume, promises will be kept and broken, and the keepers of official secrets will try some more of their dirty tricks, secure in the knowledge that this was an issue which was never to arise in the course of the election. This was one name that was never called. When it came out in America that covert actors had been set on by the President to circumvent the will of Congress, politicians of both parties, together with the maligned American media, managed to force the President onto the defensive, and, for once, into apology. Nothing of that kind has happened here. British secrecy is more secret than American secrecy. At the same time, it would appear to have been less culpable, in certain important respects, than that of several other countries. Across the world, government chicanery has risen to new levels. One aspect of this has to do with what happens when the clandestinity of government and the clandestinity of organised crime shake hands. What brings them together is the private enterprise of drug-smuggling, and the rewards and opportunities associated with that.