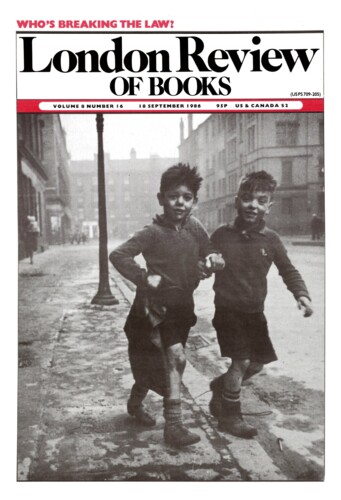

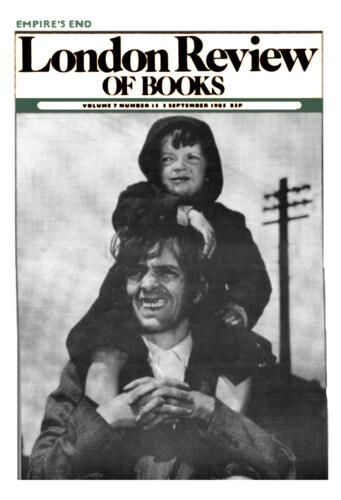

Poor Boys

Karl Miller, 18 September 1986

These are books by middle-aged semi-Scots who have chosen to publish accounts of their early lives which lay stress on the troubles they experienced, on the troubles inflicted by poverty and servitude, and on the responsibility of relatives for some of what the writers had to suffer. The question could be thought to arise of whether they are seeking revenge. Authors are not supposed to avenge themselves in their writings, but they do, and if they were to be prevented, there would be far fewer books. I am not confident that either book may be said to be well-written; that question, too, could be thought to arise. In Search of a Past affects not to be written at all – so much as researched, recorded and compiled. But the editorial method which is applied to the data has much to display that is well-spoken. They are both interesting books because they tell interesting stories, and are arranged to dramatic effect in interesting ways. Ralph Glasser’s is fresh from the oven, while Ronald Fraser’s appeared in 1984, gained a second impression last year, and is still being discussed. Juliet Mitchell has called it ‘a miniature masterpiece’, and it is a work which should have been discussed in this journal long before now, and would have been but for a miscarriage of plans. Growing up in the Gorbals, too, is liable to be called a miniature masterpiece. According to Chatto, it ‘may well become a classic of modern autobiography’.’