Kingsley and the Woman

Karl Miller, 29 September 1988

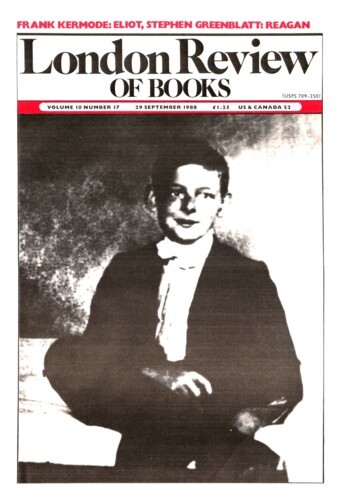

A recent photograph of Kingsley Amis shows him with a cat – a hairy cat with arched back, which is manoeuvring in relation to the author’s typewriter. The author’s face wears a witch’s smile of appreciation. He is clearly familiar with and fond of that cat. The smile may have come as a surprise to connoisseurs of pictures of the author which have been issued to the world. These pictures, rarely cordial, have become more and more baleful: it is as if he is holding himself back from physical assault on a reader supposed to be a trendy and a lefty, which is, indeed, what many of his readers have always been. The smile contrasts, moreover, with the expression to be imagined on the face of the male lead, Patrick Standish, in Amis’s novel of 1988, Difficulties with girls, when the cat in Patrick’s life pays him a visit. You feel at first that on a bad day (there are quite a few) Patrick might give it one of the kicks that the novelist seems about to direct at his readers. Then it turns out that Patrick rather likes it after all. But then it turns out that the female lead, his wife Jenny Standish (née Bunn), unreservedly cherishes their cat. All this could suggest that Amis isn’t altogether sold on Patrick Standish.’