The Italian writer Primo Levi died a year ago, on 11 April 1987, to the dismay of his readers, and The Drowned and the Saved may well be the last of his writings to be translated and reviewed in this country. There was a time when it must have seemed to many that he would never receive a bad review, or even a cross word. His first book, If This Is a Man, about his months in Auschwitz, and its sequel, The Truce, were hard to fault, and the successive publications of his middle age have been greeted by an admiration responsive both to his skills as a writer and to his character as a man. In October 1985, however, the chauvinistic American-Jewish magazine Commentary did succeed in performing the outlandish act of disparaging Levi and his books. ‘Alas,’ wrote Fernanda Eberstadt, a German-American, the later ones are inferior to the first two, and alas, the personal character freely imparted in his writings is flawed. ‘Reading Primo Levi’ is in some respects a strong essay. The later books are in large measure accurately described, and the experience of the assimilated Jew in Italy, where the Jews came to harm under Mussolini but where they were never the strangers they have been in several other countries, is summarised in a well-informed and pertinent fashion. At the same time, the article is tainted by what seems to be a desire to inflict damage on Levi’s reputation, of a kind which may be thought to serve the ideological tendency of the magazine in which it appeared.

So what is wrong with Levi and his Levi-like writings? It is made to seem that he was a stranger, a gentleman, a ‘watcher from the sidelines’. He was ‘cursed with a tin ear for religion’. As a result, there are ‘no Jews as such’ in his Auschwitz book. She means that he could not get on with the believing Jews from Eastern Europe whose religion and traditions he neither shared nor understood. But many Jews are not believers, and are still, for most people, including themselves, palpably Jewish. He also had, the article conveys, a tin ear for the ordinary man. He is like the poet Ausonius, alas – that Silver Age abstainer from the world and connoisseur of oysters.

Literary criticism is doing here what it often does: it has gone for the faults and, in so doing, inverted the truth. When is a Jew not a Jew? When he does not accept the religion revealed in the Old Testament. The Primo Levi who is read by Fernanda Eberstadt is a man who is unable to write about Jews – though he does in fact write about them with great sympathy, believers and unbelievers alike – and who has no feeling for those people whose background and abilities are different from his own, though the joy of Levi’s work, for other readers, is that he has such feelings, that he knows himself to be, while also knowing himself not to be, an ordinary man, a worker, a man who worked as an industrial chemist and who was no less of a worker when he wrote books. The Levi who emerged from a regime of cruelty and humiliation with his judgment intact, his mind not closed, neither vengeful nor forgetful, and who wrote a noble and rational book about what had happened to him, is mentioned only cursorily and as if concessively by Fernanda Eberstadt.

It is not the case that all her objections are mistaken. But their accumulation is very far from the complicated truth. The article leads you to wonder about her religious faith, if she has one, and about where it stands in relation to the outlook of the editor of Commentary, author of a book about his ambitions for worldly success: Making it must be the least pious book that has ever been written.

The stress on Levi’s insensitivity to religion is allowed to suggest that all Jews are religious, and there are readers for whom this might signal the corollary that all Jews are Zionists, and are likely to be supporters of Israeli government policy. By these standards, Levi would appear to be an imperfect Jew, and this could well be an opinion that underlies the talk about his later books being not nearly as good as his earlier ones. The principal reference in his writings to Israel is, from a Zionist point of view, tin-eared. The reference occurs in this last book of his, a collection of pieces which revert to themes pursued in If This Is a Man: ‘Desperate, the Jewish survivors, in flight from Europe after the great shipwreck, have created in the bosom of the Arab world an island of Western civilisation, a portentous palingenesis of Judaism, and the pretext for renewed hatred.’ There are those for whom it is not Jewish to speak in this way about Israel.

It is odd to speak of the creation of a state as the ‘pretext’ for anything: the translator may possibly be responsible for the oddity here, as for the orotundity that precedes it. But it seems evident that there is a distance between Levi’s view of Israel and the views that Commentary chooses to publish. The second sentence of the issue of May this year refers to the first twenty years of the state: ‘Threatening to “push the Jews into the sea”, the Arab world re-formulated the Nazi theory of Lebensraum in Mediterranean terms: there was no room in the region for a Jewish homeland.’ Arabs who had been expelled from their land and thrust into the condition of Jewish refugees are hereby re-formulated as imperialist aggressors and as Nazis. This is not unlike the sort of inversion a fault-finding literary criticism can produce – which is not to deny, which is indeed to admit, that the Arab leaders and polemicists of the region have had their faults, including some of those which have been identified over the years by Commentary. The magazine’s line on such matters would also appear to be remote from, and distinctly harder than, that taken in its dying days by the Reagan Administration. George Shultz travelled to the Middle East this summer to spread the word that ‘the continued occupation of the West Bank and Gaza and the frustration of Palestinian rights is a dead-end street. The belief that this can continue is an illusion.’ It is a measure of the grim recalcitrance of the region’s problems that Shultz’s message was saluted by a strike called in protest among the Palestinians of the occupied territories.

Meanwhile Fernanda Eberstadt has been practising as an expert on captivity and escape, and on the beliefs established for later generations by the children of Israel. She has written in the same magazine (June 1987) on the Book of Exodus, warning that a reading of the Bible as literature, rather than sacred text, ‘cannot lift heavenward’. In the article on his work Levi is at one point examined with reference to Leviticus. She takes exception to a story of his about a Jewish Communist, an inhabitant of the camps, who fasts there on Yom Kippur. She observes that the prisoner is following a prohibition laid down in the Old Testament, but that a rabbinical ruling had allowed Jews to eat in the camps on Yom Kippur in order to stay alive. It is not clear why this is a reproach to Levi, whose story concerns a man whose piety is idiosyncratic, especially severe. Two years after this, in February 1987, she praised a Gulag memoir by Gustav Herling. A World Apart is a ‘truly golden’ work, despite the presence in it, apparently, of a foul anti-semitism. Herling is thought to resemble Dostoevsky, whose prototypical prison book, The House of the Dead, has in it a mansion tenanted by obnoxious, caricatured Jews. A World Apart is, ‘despite’ its author’s socialism, a ‘deeply religious book’, in which she has at times the sense of ‘a man talking to God’. She displays more sympathy for this anti-semitic Moses, for this religious man who is against Jews and against the Soviet system, than she does for Jews who are not religious. Whether or not she has talked to God, she has certainly been reviewing for him.

Levi, the expert on metals, would have had no difficulty in telling the difference between gold and tin. I have heard that he was saddened by these writings of Fernanda Eberstadt’s, in which his own writings are faulted. Two months after the Herling piece was published Levi committed suicide, throwing himself down the staircase of the house in Turin where he was born and grew up, where he wrote about his life in the camp at a desk which stood where his cradle had stood, a house he shared with his wife and mother. He was 68 years old. I don’t suggest that these unfavourable writings pushed him to do what he did, though I don’t mind suggesting that the bigotry and vicarious piety they may be reckoned to contain could be classed among the negative experiences of the last months of his life. I have in fact no explanation to offer as to what happened, and it may be that no trustworthy explanation will ever be achieved.

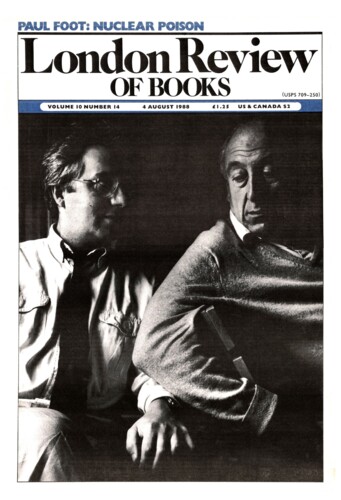

Levi was an author who, without detriment to the other people who figure in his books, wrote all the time about himself, both in frankly autobiographical and in fictional form. The modes which he adopted were such as to license elisions and lacunae, to enable him to leave out bits of his life – a procedure which would seem to be connected with his scepticism about what can be known about people by biographers. In Moments of Reprieve he remarks: ‘What the “true” image of each of us may be in the end is a meaningless question.’ In The Periodic Table he mentions a woman ‘dear to my heart’ who was murdered at Auschwitz: but the book on Auschwitz does not discuss his relationship with her. In The Wrench he creates the rigger Faussone, the practical man whose cranes girdle the world and who keeps returning, a little heavy-footed, to the house in Turin where two old aunts fuss over his welfare: Faussone was spoken of as ‘my alter ego’, and the book has to struggle to accommodate him as a second person, available for interview by Levi. These omissions and transpositions indicate that Levi could well have kept to himself any plan he may have formed to end his life. During the meeting with him a few months before his death which was recorded in an article published in the London Review (23 October 1986), Philip Roth found him as keen as mustard: here was someone who listened, with the intent stillness of a chipmunk. Levi had a high opinion of the grain of mustard, and of salt. Fascism did not like these substances. He associated the grain of mustard with his own activities, with Roth’s, with Jews generally, with the awkwardness and tartness and wholesomeness of idiosyncrasy and dissent. It was, or could be called, an impurity. It was the taste of the stranger – who might at the same time be rooted, as he himself was, in some national life.

Back in Italy, after his departure from Auschwitz and his wanderings through Europe, the ‘heart within him burned’ to speak and to write about the camp: ‘I felt like Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, who waylays on the street the wedding guests going to the feast, inflicting on them the story of his misfortune.’ He began work as a chemist in a paint factory. Then came the meeting with the woman whom he was to marry. ‘In a few hours I felt reborn and replete with new powers, washed clean and cured of a long sickness, finally ready to enter life with joy and vigour; equally cured was suddenly the world around me, and exorcised the name and face of the woman who had gone down into the lower depths with me and had not returned. My very writing became a different adventure, no longer the dolorous itinerary of a convalescent, no longer a begging for compassion and friendly faces, but a lucid building, which now was no longer solitary: the work of a chemist who weighs and divides, measures and judges on the basis of assured proofs, and strives to answer questions.’ These remarks do not describe the kind of book which runs easily to sequels, and which is easy to live up to. Nor do they describe the sort of thing we are supposed to like very much. The first two autobiographies, that is to say, are the kind of book to which a tradition of literary interpretation has been inimical, imagining for itself a literature of impersonality, in which autobiography is subsumed, invisible.

Philip Roth’s article refers to this issue in referring to the later book If Not Now, When? – Levi’s ‘Eastern’, an adventure story of Jewish partisans during the closing months of the war, led by the Communist fighter-fiddler Gedaleh. ‘With his left hand he snatched the gun from the Pole’s hands, and with his right he gave him a violent blow to the ear.’ Roth says to Levi in the course of the interview embodied in his article: ‘Your other books are perhaps less “imaginary” as to subject-matter but strike me as more imaginative in technique. The motive behind If Not Now, When? seems more narrowly tendentious – and consequently less liberating to the writer – than the impulse that generates the autobiographical works.’ Levi explains that he had amused himself by writing a ‘Western’ and that he had wanted to write a hopeful book.

I wished to assault a commonplace still prevailing in Italy: a Jew is a mild person, a scholar (religious or profane), unwarlike, humiliated, who tolerated centuries of persecution without ever fighting back. It seemed to me a duty to pay homage to those Jews who, in desperate conditions, had found the courage and the skill to resist.

I cherished the ambition to be the first (perhaps the only) Italian writer to describe the Yiddish world. I intended to ‘exploit’ my popularity in my country in order to impose upon my readers a book centred on the Ashkenazi civilisation, history, language and frame of mind, all of which are virtually unknown in Italy, except by some sophisticated readers of Joseph Roth, Bellow, Singer, Malamud, Potok, and of course yourself.

Levi’s explained intention does not mean that there is no autobiography in the book. The wish to evoke a Jewish resistance to Nazism relates to a history which comprehends his own writings and example. And in the portrayal of the mechanic Mendel there is a portrayal of Levi. Philip Roth is right, however, to point to the limitations of the book, and to point to a law of Levi’s work in general: the less imaginary it is, the more imaginative – the more literal the better.

Levi’s words bring to mind the art of the Russian Jewish writer Isaac Babel, who rode with Budyonny’s Red Cavalry after the Revolution, through scenes of hardship and atrocity. Babel’s art is imaginative, figurative. It has been said, by Dan Jacobson, that he ‘aestheticises’ his response to violence. This tendency has no counterpart in Levi, and it may be doubtful whether it could live with the subject-matter of the camps. Babel’s bad times could be turned into art – an art which has been seen to release him, as it were, from his subject, and which has also been seen to hesitate. He felt imprisoned by his religious upbringing in Odessa, and was to remember ‘the rotted Talmuds of my childhood’. And he was drawn to the grace and violence to be found among his Cossacks. But he was also drawn to the Jews whom he met in their Polish villages, victims of persecution and war, ‘old Jews with prophets’ beards and passionate rags’, to their ruined ghettoes and synagogues. To such scenes his narrator is introduced by the shopkeeper Gedali, believer in a peaceful Revolution. Levi’s Gedaleh and Babel’s Gedali are opposing faces of the Central European Jew in times of crisis.

Action, power, are thought to be contrasted, in Babel’s stories, with learning, devotion, resignation, suffering – those Jewish things. His ambivalence is a bespectacled look at the long legs of the divisional commander, which were ‘like girls sheathed to the neck in shining riding-boots’. The image – summoned by a narrator whose exhausted dreams are filled with girls – is like nothing we would expect to discover in the literal Levi. But the literal Levi is a writer who has his own way of interesting himself in the contrasts which have been attributed to Babel. Levi was interested in action, purpose, work, and capable of them. And this capacity pulled against a reclusiveness, and perhaps a hopelessness, which can be surmised in some of what he wrote, but are far from being the point of what he wrote.

Work is the supreme subject in Levi, and he can be very eloquent about it. ‘We can and must fight to see that the fruit of labour remains in the hands of those who work, and that work does not turn into punishment.’ ‘Perhaps the most accessible form of freedom, the most subjectively enjoyed, and the most useful to human society, consists of being good at your job ... ’ These statements are from The Wrench, where Faussone is good at his job and Levi is good at getting this across. There can be no doubt that he had an ear for what such people have to say for themselves. Faussone talks about ‘the way we bent our elbows’ – an expression (for eating and drinking) which I have heard spoken in English, but which I had never before seen written down in a book. Book-writers, Faussone says, produce works ‘which may be beautiful and all that, but, on the other hand, even if they were a bit defective, excuse the expression, nobody would die, and the only loser is the customer who bought them.’ I have heard that before too, but not from any writer. A builder friend of mine once talked to me about mistakes made by builders. These mistakes mattered – whereas ‘in the arts it doesn’t matter if you foul up.’

Levi’s double life as chemist and writer suggests that if art and work need to be separated, according to a certain sense of what it is to be a Jew, art and work are nevertheless very often the same. I like to think that he would have accepted that art is work, that the work that frees us, and is not just ‘punishment’, is art, and that anyone who uses his imagination is an artist. The categorical difference of the modern world, between artists and others, does not come well out of his reports. His chemistry is intriguing from this point of view. Here was a second double life – that of a scientist who was also an artist, a chemist who was also an alchemist, a businessman who was also a magician. He was as keen as mustard, and as Doctor Faustus. The Periodic Table reveals that the ancient magic of transmutation and alembics persisted in Levi’s laboratory. The book has fumes, stinks, bangs and fiascos. There is more than a hint of the search for the philosopher’s stone. It takes its structure from a set of correspondences between elements and persons, and the old definition of temperament as a mixture of qualities is present to the reader’s mind – the same definition that permits us to think of Faussone as a part of Levi, or as his alter ego. Levi’s paints actually manage to come to life as human beings in The Wrench, a less fanciful book which nevertheless claims that ‘paints resemble us more than they do bricks. They’re born, they grow old, and they die like us; and when they’re old, they can turn foolish, and even when they’re young, they can deceive you, and they’re actually capable of telling lies, pretending to be what they aren’t: to be sick when they’re healthy, and healthy when they’re sick.’ A bricklayer might add that human beings can be bricks, that bricks can ail and cheat, and foul up.

The work that Levi valued is of an order to which Auschwitz – with the lying motto over its gates, Arbeit macht frei – was built to be antithetical. In the camps, work was imposed on the prisoners with the aim of exploiting their efforts and of destroying them. It bears a hideous resemblance to the blighting, punishing sorts of work which are common in the world at large. And yet there was a work of survival to be attempted in the camps. Intelligence, vigilance, practicality, cunning, luck, friendship – Levi was crucially helped by donations from an Italian workman he barely knew, and by the exercise of his skills as a chemist – kept you going, in some few cases, and made you free. But most of those who stayed alive were ‘prominents’, or Kapos, prisoners who were placed in authority, or members of the Special Squads who assisted with the killings.

One of the late pieces in The Drowned and the Saved casts doubt on this work of survival: ‘the worst survived,’ he writes. In 1946, a ‘religious friend’ told him that he, Levi, belonged to an elect: ‘I, the non-believer, and even less of a believer after the season of Auschwitz, was a person touched by Grace, a saved man.’ The friend felt Levi had survived ‘so that I could bear witness’. Levi goes on to insist that the real witnesses are those who died in the camps, and that those prisoners who did not were mostly compromised people or privileged people: Solzhenitsyn is cited as making the same point about the pridurki – the ‘prominents’ of the Gulag system.

The book is no sequel to If This Is a Man, but its explications are never without interest. ‘In the Lager, colds and influenza were unknown, but one died, at times suddenly, from illnesses that the doctors never had an opportunity to study. Gastric ulcers and mental illnesses were healed (or became asymptomatic) but everyone suffered from an unceasing discomfort that polluted sleep and was nameless.’ There is a chapter which discusses the letters from Germans – ‘good Germans’ in the main – which were sent to him in response to his book about the camps. An eager public woman appealed to him with the story of her charwoman, who had proved herself at fault. The cleaning woman had said that her husband had had no choice but to obey his orders to shoot Jews. The correspondent explained: ‘I discharged her, stifling the temptation to congratulate her on her poor husband fallen in the war.’ There is a ‘Middle Eastern’ recalcitrance here. Another chapter, on the Kapos and the Special Squads, exhibits what must surely be judged an analytic understanding of the concentration-camp system set up by the Nazis – something Eberstadt is inclined to deny him, believing that the camps are insufficiently construed in the Auschwitz book as an institutionalised anti-semitism specific to Germany and politically-determined: she thinks it is soft of him to see them as belonging to a universal latent hostility to strangers. The chapter exposes a factor of complicity, and regards it, one might think, as a German invention. The Special Squads were the Nazis’ ‘most demonic crime’, representing ‘an attempt to shift on to others – specifically the victims – the burden of guilt, so that they were deprived even of the solace of innocence.’

He never forgave the Nazis; they were always his enemies. This was not, however, ‘personal’. He is among the least ego-bound of book-writers, at all times able to look beyond himself and his community. Two occasions in the book about his partisans quietly illustrate this. In the book, Line has been Leonid’s woman, and has gone with Mendel. By then a ‘desperate man’, Leonid is dispatched as such on a desperate mission, and is killed. Who can be said to have killed him? Mendel tells Line: ‘The two of us.’ Not long afterwards, his attention fixed on the sufferings of those Poles who had caused their Jews to suffer, Mendel falls silent, thinking: ‘Not only us.’ For Fernanda Eberstadt, Mendel is ‘a worrier afflicted with an ability to see his enemy’s side of the question’. Those she doesn’t like are ‘cursed’ or ‘afflicted’. There’s religion in that.

Levi’s statement to Philip Roth did not mention Babel, but it did mention another Isaac – the Yiddish writer, Bashevis Singer. There is a story of Singer’s, one of a collection due to be published soon in this country, * in which Levi, or a part or perception of Levi, is perhaps faintly distinguishable. ‘The Jew from Babylon’ is an enthralling tale about a Jewish sorcerer, a believer in the faith, hated by demons and disapproved of by rabbis, who in old age endures a turmoil which ends his life. Singer is a writer of standing in the matter of when, in what he sees as the ‘disappointing’ modern world, a Jew is not a Jew. Modern Jews, he affirms, are greedy creatures, tormented by their too many opinions. It could well be asked if his is an Orthodox fiction. Is it that of a vicarious believer, if such a person is possible? Is he an aesthete of the subject? Everything he writes is Jewish in the sense that everything he writes is conscious of the Jewish faith, if that can be said without relinquishing the thought that there are such persons as unbelieving Jews. But there is some instability in the dark professions of faith which he records, in his acerbities and fatalities. In one of the new stories a ‘recluse’, once a womaniser, says: ‘One step away from God and one is already in the dominion of Satan and hell. You don’t believe me, eh?’ Do we believe him? Is this some Jewish joke? Singer can, after all, be very funny.

His religion is as much as anything the regression to a past of obedience, disobedience, sin and doom. Such things are celebrated in his stories with a richness and unction which might appear to make a renegade of Babel and certainly of Levi. Singer’s religion is also a feeling for the power of the community to censure and reject. This power is apparent in the story of his sorcerer, together with the fine shades of ambivalence which attend his work. It is a story in which the case of Primo Levi, that of a dissident, gifted, magical, mustardly Jew, might at moments be thought to be implicated. But then so might that of the writer of the story, who may be more heretical, more of a stranger to his faith, than the Gentile reader immediately recognises. The story celebrates both the sorcerer and his rejection. We mourn his fall. ‘In the morning they found him dead, face down on a bare spot, not far from the town. His head was buried in the sand, hands and feet spread out, as if he had fallen from a great height.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.