Edward Timms

Edward Timms is the author of Karl Kraus: Apocalyptic Satirist and co-editor of Visions and Blueprints: Avant-Garde Culture and Radical Politics in Early 20th-Century Europe, a collection of essays to be published by Manchester University Press. He is a fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge.

Rendings

Edward Timms, 19 April 1990

As the debate about German identity enters a new phase, the work of Marcel Reich-Ranicki acquires a special interest. His career crosses several ideological frontiers: from Pilsudski’s Poland to Hitler’s Germany, from the Communist East to the capitalist West, from traditional Judaism to secular modernism, from radical dissent to conservative orthodoxy. For the last three decades Reich-Ranicki has been a dominant figure in West German literary journalism. His position in 1990, as he celebrates his 70th birthday, has a double aspect. For some his career is an exemplary instance of German-Jewish integration. For others it signals the end of a great tradition of critical dissent.

Wonderland

Edward Timms, 17 March 1988

‘Mayn’t your politics simply be the result of sexual maladjustment?’ This question, unobtrusively formulated in Stephen Spender’s Forward from Liberalism (1937), lurks as a sub-text in some of the most significant writings of his generation. For authors like Auden, Isherwood and Spender, the struggle for sexual freedom was a stimulus to political dissent. Around 1930, the centre of gravity both of their lives and of their writings was displaced to Weimar Germany, where a Reichstag committee on the penal code had resolved to lift the criminal sanctions against homosexuals. Germany was the country where sexual freedom and social progress seemed to go hand in hand. And the fact that the Soviet Union had been the first European country to revoke the laws against homosexuality gave Communism a particular appeal. In conservative Britain, by contrast, male homosexuals risked imprisonment and disgrace. And a crippling system of censorship made it impossible to write frankly about feelings.

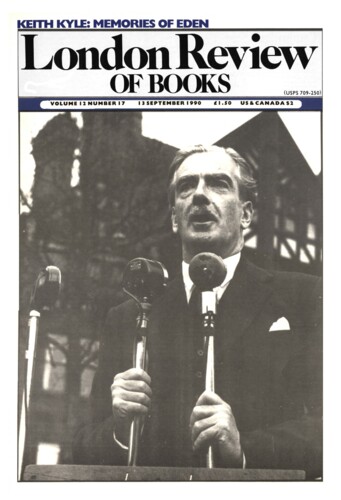

Nechaev’s Catechism

4 June 1987

Rosa with Mimi

Edward Timms, 4 June 1987

‘It is only by accident that I am whirling in the maelstrom of history,’ Rosa Luxemburg wrote from prison in September 1915; ‘actually I was born to tend geese.’ The subject of this absorbing biography is Luxemburg the goose-girl, the ‘hurt child’ who, according to Elzbieta Ettinger, lurked within the ‘famous revolutionary’. Drawing on previously unknown private letters, this book portrays Luxemburg as a socially insecure and emotionally vulnerable woman. The question left unresolved is how a person so frail and fallible could have become one of the most charismatic figures in the history of revolutionary Marxism.

Pieces about Edward Timms in the LRB

Women: what are they for?

Adam Phillips, 4 January 1996

For anyone interested in the history of psychoanalysis, or indeed, in how people start having new kinds of conversation, The Minutes of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society are an inexhaustible...

What did Freud want?

Rosemary Dinnage, 3 December 1992

The sharpest comment in Freud’s Women – a huge book, but consistently readable – comes at the end. It would be eccentric, say the authors, to conclude after five hundred-odd...

Modernity

George Steiner, 5 May 1988

Memories would seem to come in waves. Just now the Twenties and the Thirties have taken on a vivid presence. Their music, their arts, their decorative styles and fashions are being rediscovered...

How to be Viennese

Adam Phillips, 5 March 1987

In Fin de Siècle Vienna, politics had become the least convincing of the performing arts. Life, Kraus wrote, had become an effort that deserved a better cause. By the turn of the century,...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.