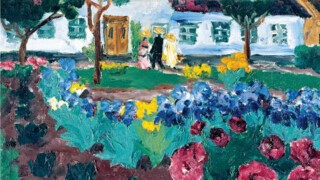

Angela Merkel had a bad start to 2019. The right-wing AfD was on the rise. The reaction of the German security services to the race riots in the East German town of Chemnitz had raised questions about right-wing infiltration of the state apparatus. And then came a request from the National Gallery in Berlin for the loan of two pictures that hung in Merkel’s chancellery office. Both were by Emil Nolde. Brecher (1936) was a typically Noldean seascape, dark blue-green breakers against a glowing red sky. The other painting was less ominous: a garden picture from 1915, Blumengarten (Thersens Haus).

Merkel had chosen the Noldes when she first became chancellor in 2005 to replace the garish work by Georg Baselitz with which her predecessor, Gerhard Schroeder, had decorated the office. Nolde had seemed a safe choice: less ostentatious than Baselitz, typically Merkel, down to earth, even a little pedestrian. He and the other Expressionists of the Brücke group had come to be seen in the Federal Republic as the epitome of a comfortable German modernism, far less edgy than Otto Dix, George Grosz or Max Beckmann, let alone the wild men of the 1970s and 1980s such as Joseph Beuys or Anselm Kiefer.

It helped that Hitler’s personal distaste for Nolde’s work is well attested. His paintings featured prominently in the exhibition of degenerate art that opened in Munich in July 1937, and from 1941 until the end of the war he was banned from exhibiting or selling his paintings. Among the most celebrated of his pictures in postwar Germany were the small-format watercolours usually known as the ‘unpainted pictures’. Nolde said in his memoirs that he couldn’t stop himself working on them, even in the face of repression and regular inspections by the Gestapo. ‘I occasionally worked furtively in a small, partly hidden room,’ he wrote:

I had been stripped of the right to obtain materials and it was almost only my small, special ideas, which I was able to paint and capture on tiny sheets, my ‘unpainted pictures’, which were to become large, real pictures when they and I were allowed to. Our beautiful picture room … had, through the ban, become the prison of my pictures, lonely and locked away.

This text was crucial for Nolde’s postwar reception. He was already well known before the war, but after 1945 his status as a martyr of the Nazi regime made him a cultural anchor of the Federal Republic. In 1952 when the order of Pour le Mérite was reintroduced, President Heuss made sure that Nolde was one of the first recipients. His villa and studio became sites of pilgrimage. The story of his persecution formed the basis of Siegfried Lenz’s bestselling 1968 novel, Deutschstunde (‘German Lesson’), which has recently been made into a film.

The Social Democratic chancellor Helmut Schmidt started the practice of hanging Nolde’s dramatic seascapes in the otherwise spartan chancellery, then still in Bonn. Schmidt claimed that it was Nolde’s persecution by the Nazis when he – Schmidt – was a teenager that had turned him against the regime. With the help of Henry Kissinger and the Guggenheim Museum in New York, Schmidt worked assiduously to promote Nolde’s work in the United States. He liked to boast that thanks to their combined efforts the Germans had dethroned the French Fauvists in the international market.

The impact of these efforts to canonise Nolde has been long-lasting. As recently as last year the Scottish National Gallery organised an exhibition of Nolde’s work under the title Colour Is Life.* ‘Nolde felt strongly about what he painted, identifying with his subjects in every brushstroke he made, heightening his colours and simplifying his shapes, so that we, the viewers, can also experience his emotional response to the world about him,’ the blurb for the exhibition blandly proclaimed. ‘This is what makes Nolde one of Germany’s greatest Expressionist artists.’

The problem for Merkel’s staff was that the conventional story of Nolde’s survival under National Socialism was a self-serving postwar myth. His paintings reflected not only his ‘emotional response to the world about him’, but a profoundly troubling nationalist and antisemitic politics. And the National Gallery in Berlin was planning a blockbuster exhibition to expose this.

The show was conceived by two historians: Aya Soika of Bard College, and Bernhard Fulda of the University of Cambridge. Their efforts to excavate Nolde’s past date back to 2003. Their inquiries were triggered by the discovery that in 1933 Nolde denounced his fellow Expressionist Max Pechstein as a Jew to the Propaganda Ministry. Pechstein wasn’t a Jew, but he and Nolde had been locked in a fierce professional rivalry since before the First World War. For Nolde it was clear that Pechstein was part of a Jewish cabal that dominated the art market and the review pages of the major newspapers, and was bent on marginalising the more authentic German art that he claimed to represent.

For many years, the foundation that manages Nolde’s estate refused to respond to queries from Soika and Fulda. But in 2013, faced with incontrovertible evidence of his Nazi sympathies, its new leadership decided to grant them unrestricted access to the archive. The result was a sensation. The exhibition (which ran until 15 September), the catalogue and an accompanying volume of documents lay to rest the myth of Nolde as a brave survivor of the Nazi regime. In its place they put a complex and unsettling history of a man who was both exponent and object of a German cultural nationalism that spans the period from the Wilhelmine Empire to the Federal Republic. What becomes clear is that Nolde was not a ‘Nazi artist’ in the simple sense that he conformed to a particular formula, but in the far more active meaning of that term. He and his wife, Ada, also a painter, were fervent believers in National Socialism and active participants in the struggle to define and promote a new art for the Third Reich. The fact that they ended up marginalised by the regime never shook their faith.

As Soika and Fulda show, the efforts to promote Nolde as an artist to rival the French go back to the years before 1914, when Nolde found himself at war with Max Liebermann and the Impressionists who controlled the Berlin Secession. For Nolde their work was an expression of a morbid Jewish and Francophile tendency that he was determined to overcome. Against their crowd-pleasing talents he styled himself a new Rembrandt, misunderstood and ignored by his contemporaries. In the aftermath of the First World War, as his reputation grew, the Noldes’ nationalist commitment was unwavering and their antisemitism public knowledge. The question was not where they stood, but whether their passionate advocacy of the nationalist cause would be reciprocated by Nazi favour.

As the party’s popularity surged, it remained an open question. Hitler’s tastes were conservative. And those associated with the Militant League for German Culture (Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur) vigorously denounced the work of Nolde and other Expressionists. But it was hard to imagine that such thuggish views would prevail once Hitler took power. In 1933 well-informed cultural observers were convinced that Nolde’s moment had arrived. To celebrate the Nazi seizure of power the couple flew the swastika from their country home. In 1933 and 1934, without any opposition from Goebbels, two successive curators of the National Gallery sought to establish Nolde as the German artist par excellence. On 9 November 1933 he went as Himmler’s guest of honour to a dinner at the Munich Löwenbräukeller to mark the tenth anniversary of Hitler’s failed Putsch. As he gushed to Ada, writing in the first person plural,

the celebration was deeply moving. We saw and heard the Führer for the first time … The Führer is high-minded and noble in his goals, an inspired man of action. Only a swarm of dark spectres are responsible for clouding him in an artificially created cultural fog. But it appears that soon the sun will break through, dispersing the fog.

In 1934 Nolde joined the Nazi Party and published the second volume of his memoirs, immodestly titled Jahre der Kämpfe (‘Years of Struggle’), detailing his battles with the Jewish art establishment between 1902 and 1914. As the art historian Ernst Gosebruch wrote to Carl Hagemann, the effort to ingratiate himself wasn’t subtle. ‘As to the numerous antisemitic and all too Germanic passages of the book, they correspond to feelings that we have known for years in Nolde. It is hardly tasteful that they should have appeared at precisely this moment.’ But Nolde saw nothing wrong in currying favour with the regime. He remained convinced of his mission to lead the national cultural revival. Though he had his enemies among the Nazis’ cultural bureaucrats, his supporters included powerful figures like Carl Schmitt, at the time Goering’s lawyer.

It was Hitler himself who would determine Nolde’s place in the new regime. Realising the significance of the Führer’s approval, Nolde’s friends in Munich sought to position what they took to be his most fetching pictures – notably his famous sunflower canvases – in places where Hitler was bound to see them: in the private apartment of ‘Putzi’ Hanfstaengl, for example. But Hitler was unmoved, and it was on his instructions that the second Nolde-loving head of the National Gallery was dismissed in 1934. Hitler’s scorn ultimately led to Nolde’s inclusion in the degenerate art exhibition three years later. But as an investigation led by Fulda has revealed, even this is not without irony. The reason so many paintings by Nolde were included and subsequently impounded was that his work had been bought in such large quantities by public galleries. In the early years of the Third Reich, more of his work was acquired than that of any other contemporary artist.

Nolde and his wife were deeply hurt by their inclusion in the show. But they quickly slotted the experience into the familiar narrative of Nolde’s artistic martyrdom. Their belief that he should lead German national culture was so fervent that they almost out-Nazied the Nazis. Given their unimpeachable nationalist record they saw no reason to accept their exclusion from the official culture of the regime. Citing their nationalist credentials and Nolde’s party membership they lobbied for his rehabilitation. And not without success. Nolde was publicly cleared of any taint of Jewish ancestry and from 1939 his work no longer featured in the degenerate art show.

With the outbreak of war, which the couple celebrated enthusiastically, came hope of a full comeback. The Noldes were visited by a Gestapo officer around this time but, as Fulda establishes, he didn’t come to conduct an inspection but to enjoy the company of the famous painter and his wife. He left with their best wishes, sent them tokens of his appreciation and received an invitation from Nolde to return whenever he could. Nevertheless, the hoped-for rehabilitation wasn’t to be. As the war intensified so did Nazi control of the art scene. Thanks to the membership dues he paid to the Nazi art association, administrators became aware of the extraordinary income Nolde derived from booming sales. In 1940 he was one of the highest grossing artists in the Third Reich. It was the scandalous extent of his success that led Reinhard Heydrich to demand an outright ban on his work, and from 1941 Nolde was forbidden to paint even in private.

The new historical narrative produced by Soika and Fulda is a work of painstaking archival research. But as they are at pains to stress, tough questions should have been asked about Nolde long ago. His party membership and antisemitism were hidden in plain sight. The unexpurgated first editions of his memoirs, complete with grotesquely antisemitic passages, can be consulted in any major German library. Already in the 1960s his party membership was an open secret. But as his popularity grew, in part because of the story of his persecution, the significance of his politics was denied. In 1967 the philosopher Walter Jens claimed that Nolde’s artistic genius trumped his politics. ‘With every drawing and with every watercolour’, he wrote, Nolde ‘overpainted’ his own ideology. The task of later generations was to rescue his work from the interpretation put on it by its own creator.

If one accepts that premise then even the most shocking archival revelations are irrelevant. The most powerful thrust of Soika and Fulda’s reinterpretation is therefore directed precisely against Jens’s argument. As they show, for Emil and Ada Nolde the connection between art and politics was not incidental. Their work and life was a single unit governed by a narrative of national heroism. Nolde’s painting was programmatic from the start, directed first against the hegemony of French Impressionism and then Fauvism. In the 1920s he portrayed himself as a peasant genius who kept away from the corruption of modern urban life. In 1933 he busied himself not just with new works, but with preparing a plan for the expulsion of Jews from Germany (he envisioned a scheme of forced emigration along the lines of the later Madagascar plan). Though the Noldes later did their best to cover their tracks by destroying the relevant documents, Fulda is able to reconstruct the outline of the plan from their correspondence. Nolde was a cultural génocidaire convinced that Jewish influence must be expunged from German culture.

The motifs of Nolde’s art were neither accidental nor simply matters of aesthetic inspiration. After 1933 the North German landscapes beloved of Schmidt and Merkel were augmented by a new fascination with Nordic myth. As the Noldes made their bid for rehabilitation after 1938, he turned to Viking fantasies. The outbreak of the war was reflected in gloomy pictures of mountain castles in flames. Many of these images were destroyed at the end of the war, leading Nolde to reflect on his sacrifice for the national cause. As it turned out, it was helpful to his postwar reputation that few of these pictures survived. One of the provocations of the National Gallery show was to complete the Nolde oeuvre by re-creating these conveniently missing pictures. Nolde and his wife intended the pictures to be viewed in conjunction with a script provided by Nolde’s memoirs and aphorisms (he wrote them in a deliberately archaic German to signal his affinity with the peasant culture of Northern Germany).

The Noldes cultivated a network of influential backers and welcomed hundreds of visitors to their house, particularly young Wehrmacht officers. This work continued with unrelenting energy after the war. The aim was still to establish Nolde as Germany’s great genius, but now with the Nazi politics removed. It was in the Federal Republic that the Noldes’ long struggle for national recognition finally paid off. As Schmidt’s animus towards Fauvism made clear, however, the national character of Nolde’s art was never in question.

The ‘unpainted pictures’ – often seen as luminous glimpses of an oppositional but authentically German spirit – were key to Nolde’s postwar metamorphosis. But as Fulda shows, this story too is an artefact of curatorial politics. Nolde did not begin making smallscale watercolour sketches in response to Nazi repression. He had made such sketches as early as 1914. It took repeated reclassifications of his portfolio to create a distinct cluster of ‘unpainted pictures’ attributable to the period between 1941 and 1945. One reason he produced more of them starting in the late 1930s was that he had discovered a new technology that allowed him to translate small images onto a larger canvas. Using a Leitz epidiascope, he could project images at greater scale, trace them and then overpaint in oil. Nolde, the painter who promoted himself as the expression of an authentic German spirituality, was in fact painting by numbers. Little wonder that his studio remained off-limits even to his closest admirers.

Despite their real exclusion from the regime after 1941, Nolde and Ada remained true believers to the bitter end. In the months after Stalingrad, Nolde echoing Goebbels’s propaganda, celebrated Germany’s heroic struggle against ‘Bolshevism, Jewry and plutocracy’ and despairingly insisted on his own contribution to that struggle. The war, he told Ada in May 1943, following the dambuster raid that drowned the Möhne valley, was becoming a ‘Jews’ war’. As late as the Ardennes Offensive of December 1944 the Noldes were glued to their radio, hoping for an Endsieg and railing against Germany’s racial enemies. And though Nolde did his best after 1945 to edit his files and minimise embarrassment, he did not budge from his beliefs. As one visitor remarked, at least Nolde, unlike so many others, remained true to his convictions. In his presence, no one dared to utter a bad word about Hitler.

For those determined to adopt a strictly aesthetic approach to Nolde’s art, none of this may matter. Even the most astonishing revelation about his politics doesn’t alter the fact that he was a brilliant colourist. But Soika and Fulda have succeeded in refuting the claim that Nolde’s work was in some sense a counterpoint to his political views. The story of his opposition to the Third Reich, which informed his pictures for so many viewers, is a fantasy with its own basis in nationalism.

How was the chancellery to respond? The National Gallery accompanied its loan request with proof copies of Soika and Fulda’s catalogue. As subsequent inquiries have revealed, this was not the first time Merkel’s staff had cause to worry about the Noldes. In 2014 they had been alerted to Soika and Fulda’s early findings by an exhibition in Frankfurt. On that occasion they had decided to keep the pictures up. This time the reaction was different. Having been asked for a temporary loan of one of two paintings, the chancellor’s office sent both, with a note to say that it did not expect them to be returned.

If this was intended to stifle debate, it backfired. Merkel’s unwanted Noldes became a cause célèbre, attracting media reports from all over the world. Huge numbers visited the exhibition. Some came for the politics. Some came for the art. Nolde still has fervent admirers. And predictably there have been accusations of censorship. At least as far as the organisers are concerned, these are wide of the mark. Far from seeking to silence debate, their aim was to create one about art and how it is produced and received. It was the chancellor’s office that seemed anxious to end the conversation.

It also had to decide what to do with the empty wall. The Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, which supplies the government with artworks, offered two pictures by another Brücke artist, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Schmidt-Rottluff was a genuine victim of Nazi persecution. But as was quickly pointed out, he was just as antisemitic as Nolde, and denounced Britain during the First World War as a nation corrupted by the influence of Jewry. So the Schmidt-Rottluffs were politely declined too.

Instead, Merkel has decided to keep the wall bare. It’s easier for a politician coming to the end of her time in office to avoid controversy. No need to embarrass foreign dignitaries with the complexities of German history. Better to forget anything ever hung there. Unless, of course, the visitor has seen a photograph of, say, Merkel’s meeting with Obama, and remembers the Nolde above the sofa. That is the power of research like Soika and Fulda’s: it gives meaning even to an absence.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.