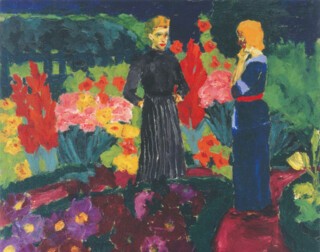

Imagine a Nolde picture, and what do you see? Perhaps a flat, brooding landscape, nine-tenths sky, with maybe a windmill or a hulking farmhouse sunk along the bottom edge. Deep lustrous colours – oils, unmixed, swirly and thick – within a wide and solid matt-black wood frame. (Nolde made them himself: he had no use for the ornate plaster gilt of a backward-looking early 20th century.) Or waving, blowsy flowers, an infinity of oranges and reds. Or an agitated sea with an oblique crack of sunset or divine mercy in it, the pure element, neither land nor shipping, nor anything else. Couples, young, old, male, female, mixed – the parallels that meet at infinity. A group of conspiratorial individuals, heavily bearded and hatted, exclusionary, farmers or Russians or uncles. Sketches from café life or the pleasure factories of Weimar. Orgiastic dancers hoofing it among candles or draped around poles. A scriptural scene, caricatural Levantine faces – hook-nosed, thick-lipped, bedroom-eyed – and a child’s Bible’s profusion of red, purple and gold. The woodcut of a bony, haunted-looking prophet, an apt cover for an old paperback edition of Dostoevsky or Conrad. South Sea Islanders, not Gauguin’s delectable milk chocolate girls chapleted with flowers, but bearded and tufty males, authentic cannibals, as the shocked painter noted in his autobiography. Or maybe one of the ‘unpainted pictures’, so-called (in other words, possible studies for subsequent paintings), almost in a now current fantasy graphic style, clouds of varicoloured steam, grotesque creatures, monsters, hybrids, gargoyles, a horsey dinosaur, a loose pig, the paper attacked from in front and behind with colour and wash, the whole thing presumably wringing wet, but better controlled and less murky than one would have thought possible.

Emil Hansen (1867-1956) was an ambivalent border creature, a Dane and a German, the son of two Hansens, one Frisian and one from Schleswig, a son of the soil, the fourth of four brothers and the first Hansen for many generations to take up a trade – he began as an apprentice woodcarver – and leave the ancestral home, and a loyal albeit non gratus German National Socialist (the pathos of that – member of a club that didn’t want him!) with a Danish passport and a Danish wife. His very strange autobiography, Mein Leben, reads as though it was composed in Danish hexameters or somehow written in woodcut; German is a forgiving language, but I’ve never read such an eccentric form of it. He tells the story of a childhood farmhand, who spoke distinctively. ‘Where’d you learn your German?’ the family ask him. ‘In the Royal Danish Army, Schleswig-Holstein regiment,’ comes the proud reply. In speech Nolde was cripplingly shy in two languages – meetings with Munch and Rohlfs pass off wordlessly, the entirety of a telephone call is given as ‘“Hello, Tschudi here,” “Nolde speaking,”’ at which point both parties hang up – somehow he was less backward about type, where he could write as he spoke, or as German has it, the way his beak grew. ‘A book by Nolde – how curious,’ his friend Paul Klee wrote when the first volume of Mein Leben was sent to him in 1931; the title of the second, Jahre der Kämpfe (‘Years of Struggle’), was surely a nod to Hitler. A Berlin bookseller was less complimentary: ‘My God, a book by Nolde – how ghastly, you never know what you’re going to get, there are as many blank pages as pages with writing.’ Together with a teenage friend, he made extensive travel plans. ‘I went to Flensburg,’ he writes (the provincial capital of Schleswig), ‘he went to America.’ For a Northman, he is unexpectedly not without humour, though other qualities such as intelligence and understanding come and go, and one is enjoined not to quote him against himself: it would be too easy, and somehow not the whole truth.

Hansen had a classic farm upbringing, with classic terrors and pleasures and constraints. No books except the Bible. Folk songs and folk tales. A father who smoked his meerschaum, a mother who sang and grew flowers. Harvesting and husbandry; ‘feeding animals is boring,’ the young Hansen wrote along a beam. Barefoot in summer. White bread only while they were bringing in the rye. Fishing and swimming. I recall a description of biting the heads off eels to kill them. He was obviously a born artist, who drew and painted with the juice of elderberries and beetroots and anything he could think of. When he was given an actual set of watercolours one Christmas, it was ‘perhaps the greatest happiness’ of his life. He wasn’t allowed to be a painter, though; he was assured he would never be able to live by it, and anyway it was an ‘impious’ calling; purse and faith sang off the same hymn sheet. He was apprenticed instead to a woodcarver (i.e. Flensburg), and lived all over Germany and Switzerland, an intense, solitary, thwarted character with few friends. In 1894, he made a series of grotesque pictures of Swiss mountains as heads, which he eventually had printed and sold in vast numbers (hideous things). With the proceeds he – belatedly – put himself through art school. Delay and rejection, deepening to humiliation and poverty, were a constant feature of those years, even decades. His life was one continuing round of obstinacy, self-conceit, sexual frustration, shyness and crises of faith. Then in 1902 he met and married Ada Vilstrup, and adopted the name Nolde from his native village; he and Ada moved to the Baltic island of Alsen; in 1904 he had his first solo exhibitions, in Leipzig and Berlin. In 1906 he made his first sale to a museum (that heroic Expressionist institution, the Folkwang, now in Essen, though it started out in Hagen). In Mein Leben he continued to style himself a young painter for another ten or fifteen years, but he was already almost forty.

In these years, various paintings and techniques signalled breakthroughs from Nolde’s earlier post-Impressionist murk, which generally looks underlit, mouldy and rained-on. Free Spirit of 1906 is a frankly hideous neo-medieval allegory, starring a Caesar or Goethe-looking Nolde himself in orange (the head uncertainly attached to the shoulders), impervious to the praise and blame offered him by the other figures robed in blue, green and magenta, but the whole thing painted in toy primary colours, and with a background of silvery tabs resembling fish scales and rather fetching pink and blue striped flooring. As I say, a monstrous work, but as declaration and emancipation it was important. He had taken the ailing Ada to Italy for a winter, and was perhaps the only German artist on record to have hated it (further proof, if proof were needed, of his militant Northernness). The Dresden group, Die Brücke, made him a sort of elderly or corresponding member, even though he didn’t stay long; the society of actual younger painters was new and strange and on the whole welcome to him.

Trollhois Garden, from the following year, is Nolde’s first heady flower painting, all hot reds and pinks, like a freshly boiled Monet. There is a sense of the briefness and burstingness of the Northern summer, a sudden clamour, colour as a quality ordinarily absent from the tweedy, marshy scene. This, though, you can warm your hands at, or if you prefer, fail a breathalyser. Likewise, the copious sunsets and cloudscapes, many of them sensational. He set up in an improvised beach hut on Alsen and, half-starved, painted sea and sky, and hammered manically on Ada’s piano. A lot of his work has the look of being open to the elements. Once they could afford it, Ada and he wintered in Berlin, with Nolde taking his sketchbook to concerts and cafés and nightclubs. The results are a sort of extra-Fauve Munch or Lautrec, wild slashes of colour, botched caricatures of faces, the occasional black of a dinner jacket or a moustache adrift among so many hothouse hats and coiffures and toilettes; you think it might be a clergyman’s prim or frantic take on temptation, with Satan demanding every single colour in the book, from lead white through the spectrum to midnight black – but delirious or austerely contemptuous, qu’importe!

In 1910 Nolde installed himself in Hamburg for several weeks and drew and painted and printed the shipping on the Elbe. These are perhaps the most characterful things he did: heroic, individualist tugs expressing themselves with oodles of smoke, the most substantial coiled black presences in curdled or crosshatched skies. He drew and painted quickly, easily able to catch things as they disappeared, clouds, sunsets, faces, postures. The variety and intensity of line and brushwork are astonishing, seemingly no two pictures alike, the paint now thick, now diaphanous, tubes or slugs or streaks of it, coming at any angle, the colour combinations, yes, tonic and opposite, but also yellow with white, red with oranges and purples, emerald with baby blue and a very deep indigo with black, and the lines in the graphic work sometimes massive and all in the locked wrist, sometimes tacking and frail like the lines on fingerprints or banknotes. A square-sailed Chinese junk is done in five calligraphic strokes. Seeing the collection of brushes in his studio, hefty, long, indelicate things more like broomsticks, you think how physical painting must have been to Nolde. Many pictures were cut down, cut up, or burned when he was dissatisfied with them. He wrote: ‘The brushstroke in a painting – the artist’s handwriting – was something I liked to see. I wanted to experience the structure and the beauty of the colours from very close as much as from a distance.’

In 1913, he and Ada participated in a small ‘Medical-Demographic’ expedition to German New Guinea; late to the colonial game, the Germans had nevertheless managed to snap up a few of the last and least unclaimed territories on the widely-flung globe. In New Guinea, the locals had unaccountably stopped reproducing, and the German FCO wanted to know why; they needed their workforce for the coconuts. Nolde – who like Kirchner and Pechstein had gone along to paint the objets in the newly established ethnological collections in Berlin and Leipzig – was the expedition’s artist. They set off by train across Russia, dropped into China, visited Japan, Korea, the Philippines, and stopped in the South Seas, with their absurd nonce-German appellations, New Hanover, Friedrich-Wilhelmshafen, the Empress Augusta River, and the like. ‘New Guinea – thou wild, beautiful land!’ he exclaimed. The journey was less influential than one might have expected – but that’s because Nolde had already got there by himself, with his revelation of colour, his seas and skies, his folksy-cum-suspicious renderings of faces. The exquisite Tugboat on the Elbe of 1910 – low black boat, black funnels, black smoke, against creamy coils of yellow water – is as exotic as anything needs to be. When I see it, I imagine it’s actually called ‘Yellow Sea’ or ‘Sea of Okhotsk’. Politically, though, the trip gave him a gloomy understanding of the omnivorousness of ‘progress’: ‘any primal state and primal people is bound sooner or later to be discovered and Europeanised. Not even a small enclave of aboriginal people will remain for posterity.’ He extended the same respect and recognition to the South Sea Islanders he saw as he gave his own relatives and neighbours in Schleswig. They lived, he said, ‘at one with nature and with the universe as a whole. With the disappearance of their primal mode of existence a part of the earth’s history is finished.’ This is one of the things that was to get him in trouble with the Nazis, that and his Expressionist style; the other side of him – vigorous, independent, Germanic, anti-French and antisemitic – was right up their alley. In Mein Leben, he refers to ‘our strong, masculine, inner, Nordic art’, and other such epithets abound. Goebbels would probably have been only too happy to make common cause with Nolde, the party member (until 1945), who involuntarily contributed the greatest number of pieces – 33, and another 1029 confiscated – to the notorious Nazi touring exhibition of Entartete Kunst (‘degenerate art’) in 1937 (some lustful Nazi critics wished to put the painter up against a wall in lieu of his pictures!). That he remained excluded – ostracised, in his own canny and lachrymose version – is entirely thanks to Hitler’s retrograde views (as if that mattered!) as an art critic; it is one further instance of aesthetics pipping usefulness and pipping sense.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Nolde hoped, in 1919, to travel again, this time to Greenland, Africa and the Himalayas – and it’s easy to imagine an alternative, ‘global Nolde’ – but all that proved impossible; the 1913-14 expedition was to remain his only experience of travel outside Europe. Instead, he settled ever deeper into local patriotism, living within five or ten miles of where he was born, devising schemes for land-drainage, travelling by keeping still (a 1920 plebiscite in which he did not participate moved his domicile from Germany to Denmark; he claimed to remember the wailing of the German locomotives when they were removed to the fatherland). In 1927, he and Ada built Seebüll, a rather grim-looking, bunkerish concrete house and studio just below the Danish border. He stayed there through the war, painting watercolours which, with mawkish effectiveness, he referred to as his ‘unpainted pictures’, and managed to situate himself as the oppositional figure he never was. Suspicious, rather, hermit-like, cantankerous, incessantly productive. Ada died in 1946; Nolde, having once remarried, in 1956, at the sort of great age that seems to be the preserve and maybe the intention of so many Nordic contrarians (Hamsun, Munch, Jünger). Emil and Ada Nolde are buried at Seebüll, and if you’re dropping down from Sylt or indeed Denmark, it’s well worth turning off for. The house is now styled the Nolde Stiftung Seebüll, the garden is kept up, and much of his work (he didn’t particularly like or need to sell, after about 1920) is held there, including almost all the pieces in the small, but exceedingly well-chosen and well-curated Edinburgh show.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.