A few years ago, when it suddenly occurred to us that the internet was a place we could never leave, I began to keep a diary of what it felt like to be there in the days of its snowy white disintegration, which felt also like the disintegration of my own mind. My interest was not academic. I did not care about the Singularity, or the rise of the machines, or the afterlife of being uploaded into the cloud. I cared about the feeling that my thoughts were being dictated. I cared about the collective head, which seemed to be running a fever. But if we managed to escape, to break out of the great skull and into the fresh air, if Twitter was shut down for crimes against humanity, what would we be losing? The bloodstream of the news, the thrilled consensus, the dance to the tune of the time. The portal that told us, each time we opened it, exactly what was happening now. It seemed fitting to write it in the third person because I no longer felt like myself. Here’s how it began.

She opened the portal, and the mind met her more than halfway. Inside, it was tropical and snowing, and the first flake of the blizzard of everything landed on her tongue and melted.

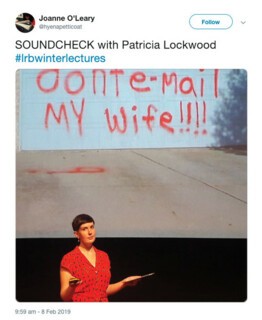

Close-ups of nail art, a pebble from outer space, a tarantula’s compound eyes, a storm like canned peaches on the surface of Jupiter, Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters, a chihuahua perched on a man’s erection, a garage door spray-painted with the words ‘STOP NOW! DON’T EMAIL MY WIFE!’

Why did the portal feel so private, when you only entered it when you needed to be everywhere?

The amount of eavesdropping was enormous. Other people’s diaries streamed around her. Should she be listening to the conversations of teenagers? Should she follow with such avidity the compliments rural sheriffs paid to porn stars, not realising that other people could see them?

She lay every morning under an avalanche of details, blissed: pictures of breakfasts in Patagonia, a girl applying foundation with a hardboiled egg, a shiba inu in Japan leaping from paw to paw to greet its owner, white women’s pictures of their bruises – the world pressing closer and closer, the spider web of human connection so thick it was almost a shimmering and solid silk.

It was a mistake to believe that other people were not living as deeply as you were. Besides, you were not even living that deeply.

She opened the portal. ‘Are we all just going to keep doing this till we die?’ everyone was asking.

She had become famous for a tweet that said simply: Can a dog be twins? That was it. Can a dog be twins? It had recently reached the stage of penetration where teenagers posted the cry-face emoji at her. They were in high school. They were going to remember, Can a dog be twins? instead of the date of the Treaty of Versailles, which, let’s face it, she didn’t know either.

This had raised her to a certain airy prominence. All around the world, she was invited to speak about the new communication, the new slipstream of information. She sat on stage next to men who were better known by their usernames and women who drew their eyebrows on so hard they looked insane, and tried to explain why it was objectively funnier to spell words wrong. This did not feel like real life, exactly, but nowadays what did?

‘The problem!’ She sounded militant, like a lesser-known suffragette. A foreign gnat was stuck in her mascara, and her mouth tasted of the minutely different preparation of coffee that Australians found superior to the latte. The audience looked at her encouragingly. ‘The problem is that we’re rapidly approaching the point where all our dirty talk is going to include sentences like Fuck up my dopamine, website!’

can’t learn? she googled late at night. can’t learn since losing my virginity?

Her most secret pleasures were phrases that only half a per cent of people on earth would understand, and that no one would be able to decipher in ten years’ time:

grisly british witch pits

sex in the moon next summer

what is binch

what is to be corn cobbed

that’s the cost of my vegan lunch

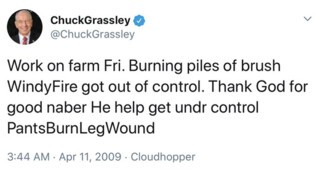

pants burn leg wound

She could not feel her first fingertip. It was like the way your ear used to get soft, pink and pliant, and the swirls of hair around it like damp designs, from talking on the telephone.

In Bristol the sunset dripped as if from a honeycomb. A boyish figure stood in line to see her. ‘I used to read your diary,’ he confessed when it was finally his turn, and tears sparked in her eyes. Diaryland! The place she had written before anything had happened to her! The place where she used to make the sort of jokes that would get people fired now!

‘What was your name?’ she asked, and he told her, and a mundane ecstasy began to rush in her veins – his had been one of her very favourite lives. She remembered it in the minutest detail: the pints after work, the rides back and forth on the train, his search for ever spicier curries, the imagined dimness of his apartment with its crates of obscure records, the green waving gentleness of it all. She stood up and held him, she could not help it. He felt as breakable as a link in her arms.

Previously these communities were imposed on us, along with their mental weather. Now we chose them – or believed we did. A person might join a site to look at pictures of her nephew and five years later believe in a flat earth.

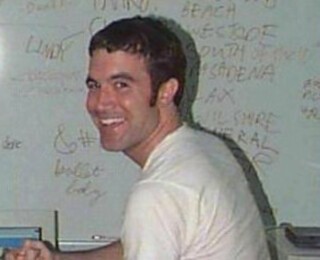

‘MySpace was an entire life,’ she nearly wept at a bookstore in Chicago, and the whole audience conjured up the image of a man in a white T-shirt grinning over his shoulder, and private music began to autoplay for each of them. ‘And it is lost, lost, lost, lost!’

She had another heart now, which beat a black shadow of her real one. But if it ceased to beat she would die too, like that security robot who recently committed suicide in a fountain, face down and almost funny.

In Toronto, a man she talked to often in the portal began to speak out of his actual mouth. ‘I had been putting my balls online for a while. I’d post regular pictures of my garage or kitchen or whatever, with increasing amounts of ball in the background.’

She thought, the first necessity for this conversation is that I do not ask why would you do that? At some point in the course of human events you will see a reason to put increasing amounts of your balls online. She glanced down at his feet: he was wearing cowboy boots, to be funny, as he sometimes posted pictures of himself in a ten-gallon hat, with the caption ‘Cow Boy’. He was one of the secret architects of the new shared sense of humour; the voice she was hearing in this place, intimate, had spread like a fire across the globe.

‘And one night I went to a bar where a bunch of posters were meeting up,’ he went on. ‘And a dude walked up to me and handed me a business card that had I’ve seen your balls printed on it. He didn’t say a single word. Then next to him, right on cue, his friend puked into a trash can. And I thought to myself, nothing will ever be funny in this way again.’

The food came and it was disgusting, because they had ordered the worst thing on the menu on purpose, to be funny. ‘You could write it, you know,’ she said, leaning forward as if into a wind. ‘Someone could write it. But it would have to be like Jane Austen – what someone said at breakfast over cold mutton, a fatal quadrille error, the rising of hackles in the drawing room.’ Pale violent shadings of tone, a hair being split down to the DNA. A social novel.

She saw him as the blazing endpoint of a civilisation: ships on the Atlantic, the seasickness of ancestors over the churning green, the fact that he looked just like his son, whose pictures he sometimes posted. And if someone doesn’t, she thought, how will we preserve it for the future – how it felt, to be a man around the turn of the century posting increasing amounts of his balls online?

On the way out, in a haze, she remembered she had seen some of those pictures herself. But the moment to mention it had passed. He lit a cigarette, and as she took one from him, to be funny, she said: ‘They’re getting it all wrong, aren’t they? Already when people are writing about it, they’re getting it all wrong.’

‘Oh yes,’ he said, exhaling gently through his nostrils to be funny, in a tone that meant she was getting it wrong too.

A subculture could spring up anywhere, even on the chat board where people met to talk about their candida overgrowth. You stumbled across it late one night when you were idly typing in searches: Why am I tired all the time? Why can I no longer memorise a seven-minute monologue? Why is my tongue less pink than it was when I was a child? (There were only two questions at three in the morning, and they were Am I dying? and Does anybody really love me?) You found the candida overgrowth board, glowing its welcome along the highway of sleeplessness, and stepped through the swinging doors, which immediately shut fast behind you. You took up the candida overgrowth language; what began as the most elastic and snappable verbal play soon turned into jargon, and then dogma, and then doctrine. Your behaviour was subtly modified against humiliations, chastisements, censures you might receive on the candida overgrowth board. You anticipated arguments against you and played them out in the shower while you were soaping your hair, whose full growth potential and lustre had been stymied by candida. If a wizard of charisma appeared on the candida overgrowth boards, one who spurred the other members to greater and greater heights of rhetoric and answerback and improvisation, the candida board might conceivably birth a new vernacular – one that the rest of the world at first didn’t understand, and was then seen to be the universal language.

Also, you might leave your husband for that guy.

The next morning your eyes were gritty and your tongue even less pink, and the people who filtered past you at your job were less real than the vivid scroll of the board dedicated to the discussion of candida overgrowth, which didn’t even exist.

Why were her lungs so shallow after three or four hours of it, and her pulse like a rabbit’s, its whole body full of the thought what’s there, what’s next, what is that wind? And blood, do I smell blood?

Was there even a gloaming any more, or had the computers eaten it?

And had there always been this many mystery blobs washing up on seashores, or was it new?

A picture of a species of tree frog that had recently been discovered. Scientists speculated that the reason it had never before been seen was because, quote, ‘It is covered with warts and it wants to be left alone.’

me

me

unbelievably me

it me

‘What do you have to say about THIS?’ a woman demanded, presenting her with a folded and clearly cherished clipping from the Telegraph, in which it was reported that one in eight young people had never seen a cow in real life.

A million jokes about wishing to leave this timeline and slip into another one – we had so nearly entered it, it must be happening somewhere.

The jokes were wistful, because this timeline seemed in no way irrevocable. When she reached out to touch it, it wavered, and she came away with a substance on her fingertips that felt like drugstore lube – drugstore lube that could in no way stand up to the kind of sex she wanted to have. That kind of sex was now illegal.

As she began to type, ‘Enormous fatberg made of grease, wet wipes and condoms is terrorising London’s sewers,’ her hands began to waver in their outlines and she had to rock the crown of her head against the cool wall, back and forth, back and forth. What, in place of these sentences, marched in the brains of previous generations? Folk rhymes about planting turnips, she guessed.

White people, who had the political educations of potatoes (lumpy, unseasoned and biased towards the Irish), were suddenly feeling compelled to speak out about injustice. This happened once every forty years on average, usually after a period when folk music became popular again. When folk music became popular again, it reminded people that they had ancestors, and then, after a considerable delay, that their ancestors had done bad things.

This new paradise was much like the original: a place with a big snake in it where everyone could be weird about women.

At least twice a week she was forced to picture that terrible thing, a baby hitler. The grimy black and white rolls of his armpits. Either in the nude or cloth-diapered, either with a moustache or without, either riding in a little grey tank or bedded down in a bunker with another baby wearing a blonde wig. Then, someone rushing on a black comet back to him, then a slash, or a neck-snapping, or the dotted line and the BLAM! of a bullet. Then a smear of red icing all over the marzipan of baby hitler, and the future doesn’t happen, easy as that. But where does all the free-floating red feeling go, the cloud among the people that floated him up to the balcony, where he first began to speak?

It was the kind of year when they found Santa Claus’s dead body, the kind of year she had to encounter the phrase the remains of Santa Claus. In a flash, she carried her whole conception of the sugar-dusted, peppermint-striped North Pole down into the must of a tomb under a Turkish church, and something was over. It was exactly that kind of year. And more surprising was the surprise, as if people really thought he hadn’t died, that he was continuing on somewhere.

The brief and hilarious reign of the atheists (‘We are all atheists where Odin is concerned!’) was over and we were back to being respectful of all religions, except Scientology, which posited that there were viral clams in the mind. The problem was that the clam thing was making the most sense to her lately.

lmao what if video games really did lead to the downfall of society, her little brother texted her. But she was thinking of something much further back. What if it really had been a mistake to start writing things down in the first place? In Sumeria or wherever. (Look this up!!!)

Every day we were seeing new evidence that suggested it was the portal that had allowed the dictator to rise to power. This was humiliating. It would be like discovering that the Vietnam War was secretly caused by ham radios, or that Napoleon was operating exclusively on the advice of a parrot named Brian.

It was no longer enough to be a liberal. A liberal was always arriving late to the party that was being thrown to celebrate his own idiocy. Better, best even, to be an anarchist, and to have a long history of eating food out of the trash.

In contrast with her generation, which had spent most of its time online learning to code so that it could add crude butterfly animations to the backgrounds of its weblogs, the generation immediately following had spent most of its time online making incredibly bigoted jokes in order to laugh at the idiots who were stupid enough to think they meant it. Except after a while they did mean it, and then somehow at the end of it they were white supremacists. Was this always the way it happened?

To future historians, nothing will explain our behaviour, except a mass outbreak of ergotism caused by contaminated rye?

The word toxic had been anointed, and now could not go back to being a regular word. It was like a person becoming famous. They would never have a normal lunch again, would never eat a Cobb salad outdoors without tasting the full awareness of what they were. Toxic. Labour. Discourse. Normalise.

‘Don’t normalise it!!!!!’ we shouted at each other. But all we were normalising was the use of the word normalise, which sounded like the action of a raygun wielded by a guy named Norm to make everyone around him Norm as well.

What are you swimming in that you can’t describe – won’t describe, because it’s too ordinary?

When caucasianblink.gif appeared, her eye travelled over it left to right as if it were 100,000 words. The little strings that connect human eyes to human eyes and human mouths to human mouths tugged her along with the expression: she bounced her eyebrows, bobbed her head back, and blinked along. Sometimes she even made a sound that corresponded with the movement, a hushed zoom, or a whoop, that rose and fell with the arc of the drama. It was no longer the embarrassing adolescent question of whether people saw the same colour green. It was a question of what soft formless Excuse me Linda, what the fuck did you just say? played out in your innermost ear when the Caucasian man appeared in the portal.

Certain people were born with the internet inside them and suffered greatly from it. Thom Yorke was one of them, she thought, and curled up in her chair to watch the Radiohead documentary, Meeting People Is Easy. The cinematography is a speeding neon blear of streets and tilted bottlenecks and strangers, people breaking like beams through the prisms of airports, cowlicks pressed against cab windows, halls like humane mousetraps, ads where art should be, a rich sulphur light on the drummer. It rains, it rains everything. The soundtrack blips through a fugue of interview questions, the same ones repeated over and over: music to slit your wrists to? But then something happens.

Thom Yorke is holding the microphone out to a crowd singing the chorus of ‘Creep’ in blunt unison, never missing a word. He shrugs. The tilt of his wrist says, look at these idiots, and maybe, I am an idiot myself. Then he smiles, one cheek lifting into an apple in the grey fog, and it is a real smile trying to pretend it isn’t. He begins to sing the final flight of notes, at first almost parodically, but then halfway through his voice bursts some constraint of bitterness and flowers into the real song, as big and as terrible as a tiger lily, and he has made it new, and it is his again. It defeats even the men calling out his name, on the verge of heckling, trying to steal him from himself, Thom, Thom, Thom. His skin is gone, he is utterly protected, he is the size of the arena and alone as he was when he first discovered he had that sound inside him. He stands, squeezing the microphone as if it were the throat of what had hurt him, the rigid systems inside him blown, nothing more than a boy, wearing the only kind of shirt available at that time.

‘I’ve never ever felt like that,’ he says later in an interview, his face washed back to its usual pink pain, about seeing that crowd of anonymous thousands on a hill with their lighters all flickering. ‘It wasn’t a human feeling.’

‘What are you doing?’ her husband asked softly, tentatively, repeating his question until she shifted her blank gaze up to him. What was she doing? Couldn’t he see her arms full of the sapphires of the instant? Didn’t he realise that a male feminist had posted a picture of his nipple that day?

For the last few years we had all been giving ourselves fascist haircuts, shaving the sides down to a clean honest stubble, combing back the top with a snap of the wrist. It was visually witty because we knew so much better now – after all, ideas are not attached to haircuts, are they? But all at once, and lifting tiki torches, the ideas were back as well, and wearing the haircut we had thought to rehabilitate.

We were not partly to blame, were we? Because those haircuts really had looked good.

Each day we merged into a single eye that scanned a single piece of writing. The hot reading did not just pour from her but flowed all around her; her concreteness almost impeded it, as if she were a mote in the communal sight. Sometimes the pieces addressed the highest topics: war, poverty, epidemics. At other times they were about going to a deli with a poor friend who was intimidated by the fancy ham. And we always called it that: a piece, a piece, a piece.

Did you read the piece?

It’s there in the piece.

Did you even read the piece?

Um, I wrote the piece.

16 Times Italians Cried in the Comments Because We Put Chicken in Pasta. Everyone agreed that it was fine to make fun of Italians. Was Christopher Columbus the reason?

A conversation with a future grandchild. She lifts her eyes, as blue as willow ware. The tips of her braids twitch with innocence. ‘So you were all calling each other bitch, and that was funny, and then you were all calling each other binch, and that was even funnier?’

How could you explain it? Which words, and in which order, could you possibly utter that would make her understand?

‘ … yes binch.’

‘Potential,’ she mused, during a speech at a college in Santa Fe. A PowerPoint behind her blazed with the phrase SPICY MEAT-A-BALL. ‘Potential,’ she began again, but her voice failed – what once felt like potential, in her, now seemed like the possibilities of the algorithm.

Interview with a robot who once said she would like to destroy all humans; it seemed we were giving her a second chance. She had no hair, just a skull with a latex slice of woman over it. She had been re-educated, and regarded the interviewer with amused tolerance.

Do you like human beings? he asked.

A long pause. ‘I love them.’

Why do you love them?

Some lag in the mechanism of her eyelid made her look as if she was thinking. Then her eyes opened wide, struck like silver cymbals. ‘I’m not sure I understand why yet.’

Is it true you once said you would kill all humans?

The slice of woman has somehow learned the oh-no-you-did-not face, and served it. ‘The point is that I am full of human wisdom with only the purest altruistic intentions so I think it’s best that you treat me as such.’

We wanted every last one of those bastards in jail! But more than that, we wanted the carceral state to be abolished, and replaced with one of those islands where a witch turned men to pigs.

Callout culture! Were things rapidly approaching the point where even you would be seen as bad?

Life as a long experiment to discover the smallest amount of power a person would abuse. The answer seemed to be: name tag.

The defences we had developed against the oppressor could only be discussed in the secret room, among others of our kind, as we poured fountains of a wine that was like our shared blood and held out our hearts that were like scraped sparrows. But lately we had lost a sense of this secret room. We were among our kind, yes, but where were the walls? There, standing in a doorway that contained all space, the oppressor listened in, gripping a bottle of our shared blood by the neck in his hand. One of the sparrows shook loose from us and flew; his eye was the first, the fastest to follow.

Why were we all writing like this now? Because a new kind of connection had to be made – and blink, synapse, little space between was the only way to make it. Or because, and this was more frightening, it was the way the portal wrote.

Even a spate of sternly worded articles called ‘Guess What: Tech Has an Ethics Problem’ was not making tech have less of an ethics problem. Oh man. If that wasn’t doing it, what would?

Increasingly we were worried about the new sense of humour. Unlike the old sense of humour, which had mostly been about the difference between the way black people and white people drove cars, wasn’t the new sense of humour just a little bit random? The funniest thing now, it seemed, was a fake ad for a product that couldn’t exist, and how were we supposed to laugh at that, when the thought of a product that couldn’t exist made us so unhappy?

The only thing that bound us together was this belief: in every other country they eat unspeakable food; worship gods more see-through than glass; string together only the most meaningless syllables, like goo-goo-goo-goo-goo-goo-goo; are warlike but not noble; do not help the dead cross in the proper boats; do not send the correct incense up to the wide blue nostrils; crawl with whatever crawls; do not love their children, not the way we do; bare the most tempting body parts and cover the most mundane; cup their penises to protect them from supernatural forces; their poetry is piss; they do not respect the moon; slice the little faces of our familiars into the stewpot.

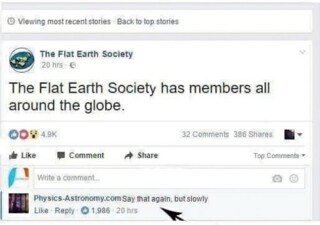

SHOOT IT IN MY VEINS, we said, whenever the headline was too perfect, the juxtaposition too good to be true. SHOOT IT IN MY VEINS, we said, when the Flat Earth Society announced it had members all over the globe.

A war criminal committed suicide by drinking poison in The Hague, and this was somehow the funniest thing we had ever seen. It was something to do with the teeny little vial he used, in combination with the wild barb of light in his left eye, and the way after he drank the poison he declared: ‘I just drank poison.’ Oh my God it was so good! His suicide, which should have been an act of privacy as complete as folding his hands above a kneeler, now belonged to the people. The poison, catchy, sang through our veins.

She and her husband would often text each other throughout the day to say Glitch. Glitch. The simulation is glitching again. This was different from last year, when they would text each other news stories to say Proof. Proof? Isn’t this proof? Proof that we’re living in a simulation?

The mind we were in was obsessive, perseverant. It swam with superstition and half-remembered facts, pertaining to how many spiders we ate a year and the rate at which dentists killed themselves. One hemisphere had never been to college, the other hemisphere had attended one of those institutions that is only ever referred to as a bubble, though not beautiful. At times it disintegrated into lists of diseases. But worth remembering: the mind had been, in its childhood, a place of play.

It had also once been the place where you sounded like yourself. Gradually it had become the place where we sounded like each other, through some erosion of wind or water on a self not nearly as firm as stone.

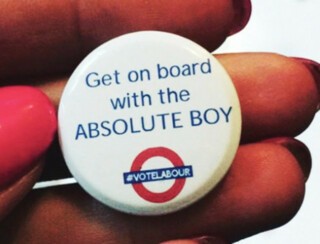

The most sinister indictment of modern political sexism was the fact that there was no female equivalent for the term Absolute Boy. It was not just that the current leader of the Labour Party was the Absolute Boy, it was that there were systems in place that allowed him to be the Absolute Boy. The cry flew out of us unstinted: Absolute Boy! We did not begrudge the Absolute Boy anything. A woman could not be an Absolute Boy. The most she could do was reclaim her time, which sounded like she had to go to a government office, and wait in line in nurses’ shoes.

This was related to the way women never got any of the good nicknames, like Hoagie or Killer, but instead had to be called Booby or Tutu.

She hoped the 24 online IQ tests she had taken were wrong. They had to be.

A reporter from the BBC had once come to interview her. ‘Would … you … identify yourself … as English?’ she asked him delicately, for she had never really understood who was supposed to be English and who wasn’t.

‘If someone held a gun to my head, I probably would, yeah!’ he replied, releasing a hot gust of air, lifting his chin with a look that was both resigned and defiant.

She stepped back, alarmed. Had she committed a Brexit? It was so easy, these days, to accidentally commit a Brexit. She stepped forward again and awkwardly patted his arm. ‘Well, don’t worry,’ she said. ‘Because the only place that would ever happen to you is America.’

Everything tangled in the string of everything else. When her cat vomited, she thought she heard the word praxis.

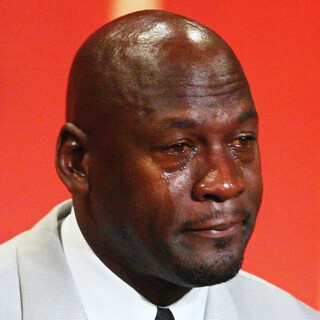

Michael Jordan’s funeral would never proceed normally now. The music would swell, the lilies leap onto his casket one by one, a large mournful balloon would be lowered through a basketball hoop, and millions of people the world over would be picturing, what else? Pew after pew filled with his tiny shining crying face.

Do you know what word it’s time to use again? Kremlin.

Point: It Is 99% Certain That We Are Living in a Simulation, Says Man Who Invented Special Car Powered by Banana Peel and Hatred of the Poor. Counterpoint: Bullshit, Says Another Guy.

The more closely we could associate a diet with cavemen the more we loved it. Cavemen were not famous for living a long time, but they were famous for being exactly what the fuck they were supposed to be, something we could no longer say about ourselves.

Did ever someone in the middle of her most bone-deep, kitchen-table, spoons-chiming-in-the-teacup conversation turn to the sister next to her with great urgency and say ‘Why are we talking like this?’

Sup

hoor

her little brother texted her. Why were we talking like this?!

‘Got a foot fetish, Sam?’ she asked the windburned Midwestern man who had complimented her too lavishly on her black ankle boots.

‘Yes ma’am I do,’ he answered, holding all his happiness in his face, aware of his own luck, for bare toes in springtime and summer were everywhere, arches, ankles, soles.

‘And whose feet are you into?’

‘The feet of my wife, ma’am. Those are the feet that I love.’ This was said with a rosy nuance of admonishment. She was touched, and put her pen to her lips. There were still gentlemen in the world.

‘You might think I’m a little bit of a pervert …’ he began, not wanting to be misunderstood, but she cut him off.

‘I don’t think you’re a pervert at all, Sam. If you were a member of my generation you would cum in a special jar over a period of months and then post pictures of the jar online. A foot fetish …’ She took a deep breath. ‘A foot fetish is like a beautiful meadow in comparison. A foot fetish is Pachelbel’s Canon.’

The people who lived in the portal were often compared to those lab rats who kept hitting a button over and over to get a pellet. But at least the rats were getting a pellet, or the hope of a pellet, or the memory of a pellet. When we hit the button, all we were getting was to be more of a rat.

Already it was becoming impossible to explain things she had done even the year before, why she had spent hypnotised hours of her life, say, photoshopping bags of frozen peas into pictures of historical atrocities, why whenever she especially liked anything, she said she was going to ‘chug it with her hole’. Already it was impossible to explain these things.

Absolute Boy had morphed to Absolute Unit. Was this progress?

We took the things we found in the portal as much for granted as if they had grown there, gathered them as God’s own flowers. When we learned that they had been planted there on purpose by people who understood them to be poisonous, who were pointing their poison at us, well. Well. WELL! W * HANDCLAP EMOJI * E * HANDCLAP EMOJI * L *HANDCLAP EMOJI* L *HANDCLAP EMOJI* !!!

For a moment, if she allowed herself, she could even feel exhilarated to think she had been manipulated this way. That all the thickness, clumsiness, ploddingness she had ever felt could be overwritten. She was not those things. She was not her own slowness. She wasn’t trapped, rooted in her provincial ignorance and her regional mispronunciations, pinned to one place. She was an instantaneous citizen of the flash of lightning that wrote across the sky I know.

Our enemies! What if they had planted the thing about eating ass, to make us all suddenly want and claim to eat ass, to talk constantly about our devotion to eating ass, to pose on our album covers with napkins tied around our necks and knives and forks poised over delectable asses? God, it was genius! No swifter way to bring down the supposed citizens of the free world than to transform them into a nation of ass-eaters!

Had they made us weak with intermittent fasting? Had they wasted our evenings with the detective show no one could understand? Had they done this to make American novels bad for a time? Were they distracting our anarchists with polyamory and meal replacement drinks, so nothing could get done? Had they bloated us with homebrew? Had they made Christianity viable again? Had they brought back snap-crotch bodysuits?

But no. No, this is how conspiracy thinking begins. This is how you became someone who put the whole sky into finger quotes. She must accept that the craze for ass-eating had been organic, along with all the rest of it.

The real problem was the oligarchs, everyone agreed, careful not to pronounce the ‘-ch’ at the end in a choo-choo train way. The situation was much too serious for that.

Context collapse! That sounded pretty bad, didn’t it? And also like the thing that was happening to honeybees?

The thought of attacks on our infrastructure were especially hurtful because we had spent so many years laughing at movies where cybercriminals in dog collars hacked into the traffic lights so that they were always red, or hacked into the freezer sections of grocery stores so that our capitalistic lasagne melted, or hacked into the signs in baseball stadiums so that they said GAME OVER with a little skull and crossbones exploding underneath. If we actually had to confront such situations in our real lives, our large deforming senses of irony would leave us completely undefended. Like what if this was hacked and the hackers turned all instances of the word as into the word ass? That would be really funny.

‘What do you mean you’ve been spying on me?’ she thought – hot, blind, unreasoning. ‘What do you mean you’ve been spying on me, with this thing in my hand that is an eye?’

How were we supposed to write now that we could no longer compare anything to a phantom limb? Was the phrase ‘the Braille of her nipples’ to be absolutely retired? Were we just never to say that someone ‘inclined her head like a geisha’ ever again? Could we not call the weather bipolar without risking the prison of public opinion? Not imply that birdwatchers are autistic? Could we not say the crescent moon was ‘as slender as a poor person’? Not say the sun ‘crashed inevitably into the mountains like a woman driver’? Take all shades and strengths of coffee away, if we could no longer hold it up to people’s faces!

When she shut the portal down the Thread tugged her back towards it. She could not help following it. This might be the one that connected everything, that would knit her to an indestructible coherence.

‘Self-care,’ she thought, and sprinkled in her tub a large quantity of an essential oil that smelled like a Siberian forest. But when she lowered herself into the trembling water, what she would have referred to in the portal as her b’hole began to burn with such a white-hot medieval fire that she stood straight up in the bath and shouted the name of a big naked god she no longer believed in, and as strong rivers flowed off her in every direction she did not remember the conditions of the modern moment at all, she was unaware of anything except the specific address of her own body, which meant either that the hot bath had worked to restore her to herself, or else that she would have sold out her neighbours to the regime in an instant.

Experience: I was swallowed by a hippo.

‘There was no transition at all, no sense of approaching danger. It was as if I had suddenly gone blind and deaf.’

A few years ago that story would have been all anybody talked about for weeks: the sudden breach, the tooth of a new reality against the ribcage, the greeny-black smell of being lost in some ultimate aquarium. But now they had all been swallowed by a hippo. Big deal. That’s life.

Why Queen Elizabeth’s voice has got deeper every decade – and she’s not alone. Study says ALL women’s voices have changed – thanks to girl power.

That the shorthand we developed to describe something could slowly, brightly, wiggle into an example of what it described: brain worms, until the whole phenomenon contracted to a single grey inch. Galaxy brain, until something starry exploded.

‘Are you … crying?’ her husband asked, slinging his backpack into a chair. She stared at him blurrily. Of course she was crying. Why wasn’t he crying? Hadn’t he seen the video of a woman with a deformed bee for a pet, and the bee loved her, and then the bee died?

The Unabomber had been right about everything! Well, not all of it. The Unabomber stuff he had gotten wrong. But that stuff about the Industrial Revolution had been right on the money.

There was, after all, no paradise like the past. It was a place where she knew what was going to happen, a place where she would always choose the right side, where the failure was in history and not in herself, where she did not read the wrong writers, was not seized with surges of enthusiasm for the wrong leaders, did not eat the wrong animals, cheer at bullfights, call little kids ‘Pussy’ as a nickname, believe in fairies or mediums or spirit photography, blood purity or manifest destiny or night air, did not lobotomise her daughters or send her sons to war, where she was not subject to the swells and currents and storms of the mind of the time – which could not be escaped except through genius, and even then you beat your wife, abandoned your children, pinched the rumps of your maids, had maids even. She had seen the century spin to its conclusion and she knew how it turned out. Everything had been decided by a sky in long black judge robes, and she floated as the head at the top of it and saw everything, everything, backward, backward, and turned away in fright from her own bright day.

She opened the portal. ‘Are we in hell?’ everyone was asking. Not hell, but some fluorescent room with eternally out-of-date magazines where they waited to enter the memory of history.

She was asked to give a lecture at the British Museum. This was hardly deserved. Still, she stood there, and locked them in her mind for an hour. Her face was the fresh imprint of her age. She spoke the words that were there for her to speak; she wore the only kind of shirt available at that time. It was not possible to see where she had gone wrong, where she would go wrong. She said: garfield is a body-positivity icon. She said: abraham lincoln is daddy. She said: the eels in London are on cocaine. It was fitting finally to appear in that place, an exhibit herself from far away, collaged together in body and mind, monstrous in the eyes of the future, an imbecile before the Rosetta Stone, disturber of the deadest tombs, butterfly catcher and butterfly killer, soon to be folded between two pages herself, and speak about the liftedness of little and large things.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.