We had been watching The X-Files at a rate of about two episodes a year; I expected to be finished when I was approximately 114 and living in a small fishing village in Japan. But ever since my husband lost half of his blood volume after a bowel resection in 2022, after the 47 days in the desert during which I personally tended his wound, the calendar had become meaningless, as had numbers. Now that the most advanced body horror could not touch us, I saw no harm in rolling ahead. I skipped all the episodes where a guy comes up through the toilet, though there were still occasional cameos of my own worst nightmares: hallways suddenly looking weird and green and other people appearing in the mirror when I was washing my face.

Otherwise it was easier than I thought. Twins were not scary to me, and neither were cults, and neither were cryptids and neither was cloning. And why should I care about alien abduction? I felt that way just being in a car. However I had a friend who spent ten days on a ventilator in March 2020 and actually whimpered, like an animal, when the topic came up in conversation. His wife, pregnant, motioned to me: no, stop, no, this is his fear. Had he dreamed it then, being raised into the air, being probed? Had he thought it really occurred, in some heavy-petalled Florida night? He was absolutely normal, what data could be extracted from him?

The sterile room, the white sheet, the scalpel – I couldn’t picture anyone picturing himself there. Then in Season Two Duane Barry appears in his eloquent T-shirt and his face is the face of absolute belief. A scar over his right eye, where he was shot in 1982 (the bullet pierced his bilateral frontal lobes). He has been Taken multiple times and will not be Taken again. Someone, anyone, must go in his stead. His brown burning face thrusts through Scully’s window, and he tapes her mouth and puts her in the trunk of his car, where her pale irises shine like fish scales. Then Duane Barry drives south through green needles. He does not look dirty but like earth itself. When he shoots the state trooper who pulls him over it is like the gun is part of his arm; it thrusts through the window in a single line. He takes Scully to the top of a bald mountain, and she is lifted into the black sky of Mulder’s greatest desire: to know.

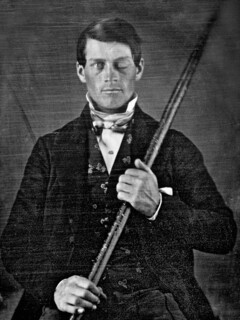

Duane Barry was based on the medical marvel Phineas Gage, a construction foreman born in New Hampshire in 1823. He had a tamping iron driven through his head while his men were blasting rock to lay new track for the railroad. He lived; he should not have lived; it made him famous. We do not even know his birthday, but we know the accident occurred around 4.30 p.m., and our documentation of his case from then onwards is so extensive that it seems like a brain through which the trajectory of events travelled with great force. Upwards, behind the handsome face, the lips like a stitch of the horizon, through the left frontal lobe and the top of the head. He appears to us in a sepia photograph with one eye absolutely awake and the other sleeping, holding the iron across his body like a rifle. The picture was only identified as Gage in 2009, fifteen years after the X-Files episode aired; previously its owners believed the subject to be a whaler, in love with his harpoon. But it is true, too, that we often don’t believe our own eyes. There is a plaster cast of Gage’s head, made at Harvard medical school in 1850, handsome as the picture.

Sometimes one appears who is the encyclopedia, who will teach us everything there is to know about a certain region – in Gage’s case, the frontal lobe. I saw again those researchers holding up slices of my niece’s brain like iris agates. I remembered how her seizures came at the intersection of her participation in the world. Rather than assuming that the research was concluded, thus closing the door on her active life, I chose to believe it was ongoing. What were the people in white coats learning? Shouldn’t I be the first to receive the news of what they found? If we had donated her whole self, what would we know now? Everything.

Gage’s blood made an inkblot, he had to be read. It is known that he was literate. It is also known that the moment before the accident occurred he opened his mouth to speak. And he did speak again soon afterwards.

How did Phineas Gage remain himself, or did he?

He did not care to see his friends, for he would be returning to his work on the railroad any day. He said his head did not hurt, but he had a queer feeling which he was unable to describe.

Two schools of thought, then as now: particular regions perform particular functions, or the brain can lay new track anywhere. Everyone mapped their own minds onto Gage. There were many myths: that he was a maniac who became completely uninhibited in speech; that he beat his wife and children, of which he had neither; that he told only lies, but only lies were told about him. He became a subject for poetry; for instance, here. We turn to him to take the top off our own heads.

I had once declared that there were certain things poets must never be allowed to know – about phantom limbs, and the invention of zero and Balzac’s coffee consumption, for starters. There was an untruth to the way we used names, wounds, last words: ‘More light, more light! More weight, more weight! Be good, be good! I love you.’ Still, it seemed to be our work. Every day we did it: moved heaven and earth to lay two facts together.

Before she is kidnapped, Scully holds the metal chip the others had implanted in Duane Barry in her hand. It has a gentle correspondence with the gold cross that she wears, given to her by her mother on her fifteenth birthday. Standing in line at the supermarket, she passes the chip over the scanner slowly and sees souls rising out of numbers, alphabet beyond alphabet, all information. It is at this moment, not later, that she begins to rise into the air.

It is Mulder who holds Duane Barry almost lovingly at the top of the bald mountain, for he is the one who knows where Scully has been taken. Shows about aliens are lit from behind, Close Encounters and ET-style, so that the light almost breathes at you over a black curve. Steve Railsback, who plays Barry, was one of several great X-Files actors born in Dallas, presumably as part of a supernaturally branded herd. (Jerry Hardin, or Deep Throat, as he was called in the show, was another.) Duane Barry is frightened like an animal. His eyes roll and his skull is like a horse’s skull. The scar over his right eye is like a topographical ridge. The actor, who studied under Strasberg, speaks his lines on the line and calls himself Duane Barry.

Perfect name, we said. Couldn’t be anything else. Though of course the writer had intended it to be Duane Garry, who not only already existed but actually worked for the FBI.

D’ye ever think acting might be really easy? my normal friend asked me once, but I didn’t. I thought it was the most wonderful thing in the world, and impossible. To speak your lines on the line, on the heartbeat. Your body has to believe it, your Hanes T-shirt has to believe it, the smear of dirt under your eye has to believe. And (it must be the reason I loved them) weren’t they the only people in the world who really needed writing?

Receiving a sudden transmission, my husband sang:

The Stanislavski method is

Fuckin’ me over I got my

Nose buried deep in the cloverAnd all the little piggies are

Shittin’ on me as I

Pretend to be a farmer in the

Country.

He received musical transmissions now, after his near-death experience. He would hold one finger up, freeze into perfect stillness, and then produce some snatch of alien radio right out of his silver fillings. Do you think ideas are original, or do they come out of the air? a student asked me. I kind of do think they come out of the air, I answered truthfully.

Now, these episodes are a leap into something higher. Scully must disappear because Gillian Anderson is pregnant. Sometimes a punk from Grand Rapids who everyone thinks is English has just gotta have a baby at the age of 24. They hid it for a while with camera angles and increasingly square taupe blazers, but beyond a certain point the secret would be out. They discussed replacing her but saw at once that it was impossible: her upper lip, for one, and the light in her eyes. So then the show becomes about something else, something deep and dark as water, it is carried rapidly past all other unsolved mysteries to ask: what if a woman were irreplaceable?

The show must become about her body: what has been done to her? What has she experienced? And all of us are breathing with the soft rising of her belly, in the room where she is being tested by the others. It is not just that she is called by her last name, or that she is the masculine sceptic while Mulder is the feminine believer. (What a man! I would exclaim as I watched David Duchovny in his little swimsuit. What a man!) It is not in the riverine quality of her voice, banked by reeds, sometimes pierced low by waterbirds. It is not even in her partner’s reaction, his one liquid larger pupil, the soft hopeless hope that he turns to her. A face to describe is paradise. As I watched, I would think sometimes of E.M. Forster: wind and water were always sweeping through his characters and leaving a freshness behind. Anderson seemed to be that freshness: something briefly inhabited, and the open door.

The real reason everyone loved the show was not because it was about alien autopsies but because it was about motel rooms. Forced proximity, everyone desired that, for how else could anything happen? The six inches between herself and Mulder, as she stood on her Scully box, turned somehow to breath, to pure intimacy. Her mouth always a little open. Yes, that was the word. First entered. Then fresh.

Now among the cherished writers of my youth I could tell which ones had been taken. Woolf and Forster floating in their nightgowns. Dostoevsky holding a potato, shaking uncontrollably on my dirt floors. The building, rising rollercoaster feeling that came as a premonition; this had its relation to writing itself. Is The X-Files kind of about epilepsy? I would wonder. It kind of seems to be a metaphor for epilepsy: missing time, weird hallways gone green, bright lights and shame on waking.

And, fatigued by the merciless and enormous day, he lost his usual sane view of human intercourse, and felt that we exist not in ourselves, but in terms of each other’s minds – a notion for which logic offers no support and which had attacked him only once before, the evening after the catastrophe, when from the verandah of the club he saw the fists and fingers of the Marabar swell until they included the whole night sky.

Ihad been thinking I might write about Adela in A Passage to India, what had happened in the Marabar caves. People did not quite know what to do with her. The text disallows her malignancy, which would be the modern explanation, even an interesting one, but not what we are given. Pankaj Mishra thinks she is merely dull; this is not right, though she is operating at a slower frame rate, like a lace fan in wavering heat. Damon Galgut writes that perhaps she is in love with Dr Aziz, and what could be more likely? But no, nothing of the kind. Adela has come over strange. She is one of Forster’s characters who strikes against the tooth in the wych elm, the animal bone of the world. She runs out of the hole of darkness, full of real thorns; something has happened to her.

We have even disappeared with her into the tear of those missing moments; in the text, we experience a small perfect abduction. Where were we? Into what unreality did we go, and which smooth stone wall did we butt against and how did we emerge full of actual spines?

The genius, of course, is that we do not see what happens in the cave, but a different heightened state: Adela in the witness box, things falling into sequence as they actually were. Not bone or fang of the world now but plasma, life as it actually happened. And so it does not matter – was it perhaps the guide? – it does not matter even to her; it all becomes part of the river.

Easy to forget that it happens to Mrs Moore too, who has always suffered from faintness, and who may have already been struck with the illness that will carry her away on the waves. In the cave she hears the echo, the boum that means all is nothing, and she goes mad for a moment and hits out at all around her, for she has felt the touch of something hideous, unspeakable, which turns out to be a baby.

Another premonition: on the train ride toward the caves, the wheels going pomper pomper pomper, Adela sees a black snake that turns out to be a tree. She calls it a snake and then everyone calls it a snake, for she has put the word in their minds. Then she realises and says no: ‘It is not a snake.’ But Forster himself juxtaposes it later (‘the snake that looked like a tree’), so that we understand a real hand may have reached out after all. Then again, as Adela confesses, for some time she has not been well. Since the caves, and possibly before. Her ears shrilling with anti-malarials, or something else, for illness is abroad in the village.

‘It’s as if I ran my finger along that polished wall in the dark, and cannot get further,’ Adela says. ‘I am up against something, and so are you. Mrs Moore, she did know.’ ‘Esmiss Esmoor’ becomes the echo and rings out: boum, nothing, boum, boum. It is gradually strewn to silence by the wind over the water.

Forster’s great image is his cow, of course, with which he begins his favourite novel, The Longest Journey. Students dropping matches on the carpet; cattle mutilated by philosophy; she is there and then not there. Cows gave us tuberculosis, which invented the modern sublime, which allowed for the free discharge of emotion within an altered atmosphere. Fever rings out in tearooms. Calm ordered gardens of language rip off their clothes and dance. It allows something to happen outside of events, and allows subsequent events to hinge on that something. Illness, which seems inert, is violent upheaval. What happened to us, we would sometimes ask each other. Will we ever find out what happened to us?

Scully’s abduction was not originally intended, it was an accident, it was life. What happened, we kept gasping, what happened? How did it get so good? But she looks so beautiful, my husband said, shocked, on the first episode of her return. I had to explain that it sometimes happens that way: that you blow like a rose, that the next person fills you past the tips of your fingers. I mean look at her, she’s a baby, we said in disbelief, at least compared to us.

Her hair a little redder, then less red. Freckles standing on her cheekbones like a new kind of frankness. She was ‘no longer examining life, but being examined by it; she had become a real person.’

Oh they really did it! my husband screamed, during the finale of Season One, when Scully first took the alien foetus, frosted blue, into her hands. Who made that little baby? Who made that thing? Because up to that point we hadn’t known that they would ever show us the clear glass flask and the fingernails, instead of only posing questions. ‘So everything’s real? Jesus, chupacabras, all of it?’

‘Did you have an unexplained event in your life last year?’ the other women ask Scully later, their eyes fixed on her with identical bovine sympathy. ‘Were you missing?’ They are, they tell her, the local chapter of the Taken, for most of them have gone missing from their beds many times. To the bright white place.

‘How do you know you’re not mistaking me for someone else?’ Scully asks in wild disbelief, looking like God’s pinkie fingernail, like no one else on earth. She looks like the Virgin Mary, my husband said, deeply distrustful. Like she should never be touched or interacted with. Yet, as one of the missing, she had been interacted with more than anyone. In the bright white place, the soft stomach slowly inflating.

All the little aliens in the Duane Barry episode are children wearing huge grey heads. Between takes they ran around, playing with the writer and everyone else on set.

‘I’d far rather leave a thought behind me than a child,’ Cyril Fielding says in A Passage to India. ‘Other people can have children.’ Phineas Gage loved his nieces and nephews, who never tired of hearing his story. His own children, non-existent, ran in clear shapes around him, neglected. From The Longest Journey: ‘With his head on the fender and all his limbs relaxed, he felt almost as safe as he felt once when his mother killed a ghost in the passage by carrying him through it in her arms.’

Lives have their facts; in composite these are history, and may be misread or played wrongly for age after age. My great-grandmother, it recently became clear, had not been an imaginary invalid. She had what you have, my mother said vaguely. Syncope. Faintness. She would come over strange. Oh, she would get dressed up for the doctor, put on the dog. Put a ribbon in her hair. She loved to put cucumbers on her eyes, they made her young. She was never the same after her son Ed went missing. She would ask to be wheeled into a special alcove of the church so she could watch the dead be raised.

‘Are you aware that you’ve been talking about yourself in the second person?’ the therapist asks Scully, as Duane Barry, in the voice of absolute belief, spoke of himself in the third. What had been done to them, up in the air? Were they still themselves? If they stood in the witness box long enough, would they see it: the liquid sequence, how things had actually happened?

I felt cheated that I hadn’t watched the show when it first aired, that Railsback might have passed from this earth before I had adequately described his face. I was in a kind of ecstasy: the live line was in him, I saw it. It was the thing that passed between people, that passed between the hands of Adela and Ronny in the car, the spark that the tamping iron struck from the rock, that was there to be believed.

Gage kept his iron rod with him to the end of his life, as a wife, as a constant companion. Well, he gave it away for a while, to Harvard, but then he wanted it back. It was special in some way, specially made at his request, and invariably described as smooth. When the rod was laid in his lap again, the line of track was a little mended; if it was his accident, it was also his survival. My iron bar, he called her, fondly, and she was the death of his death.

‘But it struck him that people are not really dead until they are felt to be dead,’ Forster wrote. ‘As long as there is some misunderstanding about them, they possess a sort of immortality.’ And yet, on the other hand: ‘Great is information, and she shall prevail.’

What happened to Gage was the most important brain injury in the history of the world, though everything it taught us kept being wrong. This was the heyday of phrenology, when we believed in organs of Veneration, Benevolence and Comparison; how could those, as the projectile passed through them, not be so thoroughly damaged that the man was changed? But against all odds it seems that Gage did remain himself, as Railsback, in his white T-shirt, remained Duane Barry. His scar made of latex. His molars drilled with water.

The mind, in the course of attempting to make its old connections, becomes all-associative, builds a terminus in the sky. My great-grandfather had a first wife, who died along with their baby in the 1918 pandemic. He was a different kind of man, my mother told me, different. He had a model train running around the ceiling of his bedroom; it ate miles every minute of the day. Why she had never mentioned him I did not know, except that now she seemed to be losing her own memory. The pomper pomper of the wheels had to go on turning somewhere, for Gage’s railway, that had changed him forever, that laid track into the future, must run.

We hope that we are not too much hurt. We expect to return to our work any day. The Scully effect is still studied: that girls who watched the show were more likely to go into the fields of science, medicine, forensics. But it hardly takes a genius, or a detective, to figure it out. It is simply that the writer says: this one is irreplaceable.

The bare feet dangling in the air. The little disappearance, and the freshness, and Duane Barry glowing like a new kind of gold.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.