People talk of painted eyes in portraits that ‘follow you round the room’. T.J. Clark, in the third of the six essays collected in his new book, Heaven on Earth, strangely inverts this. Studying the hall depicted in Poussin’s Sacrament of Marriage (now in Edinburgh), he senses that a painted figure’s eyes – eyes that are out of sight – are moving across the space, their attention straying sideways. He dwells on a thin strip of brushwork to the far left of the canvas. The strip is separated from the rest of the scene by a foreground column, the left edge of which catches light from a rear window that can just be glimpsed – a still narrower strip of glare – abutting the canvas edge. Between column and window, the darkness of the room is broken by sunshine falling on a golden headdress and the folds of blue robes below. These evidently belong to a woman, half-hidden by the column, whose back is turned to the viewer. Which way, however, does this woman turn her face? Towards the centre of the crowded room, Clark suggests at first; towards the rite of betrothal binding the Virgin Mary to Joseph, an act that causes the branch that Joseph holds to burst into flower. The woman behind the column ‘is the very figure of attention’, Clark writes. ‘She is the one of all the spectators, we are convinced, who looks hardest at the miracle.’

But that conviction falters. All that we actually apprehend is drapery. It falls in such a way that Clark can also imagine the woman averting her gaze from the big dark hall that hosts the ceremony and looking instead at the sun-filled window. ‘Could she not be turning towards it and feeling its warmth?’ After all, she is ‘in some sense an emanation’ of this light that is external to the scene. In the context of Clark’s argument, this odd inference is significant because it allows him to read the strip at the ceremony’s edge as a zone of overlap between the miracle within and the material world without. He allocates the woman with the unseen face to the latter when he speaks of her ‘bristling with energy – the energy of photons’ and nominates her a ‘figure of standing – of standing alone in the world’.

Is ‘odd’ a fair description of this method of advancing a case? It depends what sort of text we suppose that we are reading. The writings of T.J. Clark have had a gravitational force in art history since he brought out his first studies of 19th-century French art in 1973. The Clark effect has been in some sense to emphasise the singularity of artworks: his studies typically foreground a particular object and worry not only over the circumstances of its production but over the way it appears to us in its present condition. This has been for the sake of a more comprehensive materialism. The interrelation of eyes and artefact, however obsessively inturned, belongs to a larger fabric of human affairs, and the historian’s job is to characterise the fabric’s weave. Clark has been obliged to theorists of the left – Marx and Debord especially – for the conceptual tools with which to do so, and this engagement has given his work a latent political dimension. ‘Latent’ because these investigations, which have ranged out from his grounding in French modernism to look at the artistic record more generally, have described rather than prescribed. They remain histories that trace structures of causation. They argue that this or that artwork may stand, in all its distinctive obduracy, as a crux in a sequence of socio-cultural developments.

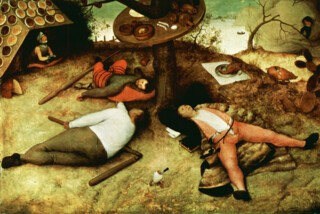

So it is with these essays, ostensibly. The piece on Poussin’s canvas of 1648 is accompanied by studies of Giotto frescoing the panel known as Joachim’s Dream in Padua’s Arena Chapel circa 1304, of Bruegel painting his Land of Cockaigne in 1567 and of Veronese painting his Allegories of Love just a few years later, in the early 1570s. Then, with an imperious sweep of the hand, Clark declares that ‘French painting of the 19th and 20th centuries’ – his former imaginative territory – ‘has little to tell us’ about our current moment, and steers us to the tail end of modernism, to the elderly Picasso painting The Fall of Icarus, a mural for Unesco’s Paris headquarters, in 1958. A coda addressed to political companions, entitled ‘For a Left with No Future’, is in effect a reading of the historical texture of the 21st century. The book makes some of the moves we expect from history writing, identifying, for example, 1567, the year of Cockaigne, as ‘a fateful year – a turning point – in the revolt of the Netherlands against Spain’ or concluding the account of Giotto by announcing that with his work ‘a new age has begun.’

But everyone has always accepted the importance of the Dutch revolt and Giotto’s innovations, whereas no one, prior to this, has expressed what peculiar ambivalences that strip of Poussin’s canvas might generate. I came away from my first reading of Heaven on Earth with rewards that were largely of that latter, rarer kind. It’s tempting to call their mode poetic, as distinct from historical. History is always more or less dogged by necessity, by cause and effect. Unseen eyes that might or might not be ‘turning’ hardly belong to necessity’s sphere. In poetry, however, we expect oscillations of sensibility. In poetry, fumbling may become force: I thought of Rilke, giddily transporting the reader as he tries on simile after simile in his ‘Rosenschale’, as I read Clark on the brushwork of Cockaigne:

The green is astonishing: no one analogy will lay hold of it. It does have a wonderful watery lightness, like marble or a throw of extra-fine velvet, but is not in the least stony or marble-smooth or aqueous. It is grassy, obviously, maybe even mossy, but dry; like a thin, almost papery covering on top of the earth; in places (towards front right, for example) it seems like the colouring of a rock face.

Poets stalk words, pounce, and steal them away: Hopkins, for instance, using a sonic coincidence to indict humanity’s mangling of the environment with his ‘Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;/And all is seared with trade.’ In comparable fashion, Clark notes – in parenthesis – that ‘Giotto is the master of folds.’ Thirteen pages pass before he retrieves the comment and couples it with a line from Dante’s Paradiso, to build on the connection and declare that for these two coeval Florentines, ‘the world is an unfolding, but as it were of a cloth that is strong, close-woven, resistant, gathered in great slow sweeps: its folds are not jagged or brilliant, corners are turned gradually, darknesses are never very dark.’

This – along with the whole reading of Giotto it caps – is majestic, revelatory rhetoric. Sometimes, it may be, the poetic manoeuvres overreach. I feel they do in the essay on the four Veronese Allegories in the National Gallery, which tries to hook their originally intended conditions of viewing (the figures are seen di sotto in sù; the canvases must once have been overdoors or similar) onto a passage from The Will to Power in which Nietzsche posits an ‘elevation and enhancement of the human’, pointing the way to ‘higher beings’. This wordplay won’t do the lifting; it collapses into mere punning. And yet Clark’s ambitions are not exactly poetic. He does at one point offer a page-long composition in verse – it concerns an alternative panel of Giotto’s – but then renounces the tactic. ‘I need prose,’ he writes. ‘I think art history in general needs prose – to circle round the emptiness, the lack of connection’ that resonates – so the essay argues – through Joachim’s Dream.

The prose, then, of Clark’s preferred style of art history – he slips in some snipes at other styles, mocking for instance ‘that far flight of historicist fancy called “looking with a period eye”’ – is a tool with which to ‘circle round’. It frets away at a specific artefact from many angles, deploying scholarship and poetic intuition, because, as Clark rightly declares, ‘Paintings are not propositions.’ Further,

They are not even like propositions. That is, they do not aim to make statements or ask questions or even, precisely, to seek assent. They are best not seen, it follows, as strings of individual image-elements or phonemes, arranged according to some overall grammar … This is not the order of the linguistic. It is an ordering of things more open and centrifugal – more non-committal – than grammar can almost ever countenance.

What then is grammar supposed to do with paintings? To what purpose should language circle? Clark returns to Nietzsche at several places in this book, and oftener still to another 19th-century fulminator, John Ruskin. The Veronese essay concludes by hailing the pair as ‘necessary madmen’. Imagine an authorial stance that straddles the two: one that tilts here towards the impassioned granularity of Ruskin’s picture-examining and there towards the swingeing recklessness of Nietzsche’s aphorisms. Like those grand scolds of the spirit of their century, Clark is buoyed up by a kind of panoptic vehemence. His accusing finger sweeps across time. ‘The essence of modernity,’ he tells us at one point, ‘from the scripture-reading spice merchant to the Harvard iPod banker sweating in the gym’, is an ‘isolate obedient “individual” with technical support to match. The printed book, the spiritual exercise, coffee and Le Figaro, Time Out, Twitter, tobacco (or its renunciation), the heaven of infinite apps.’ Elsewhere – during Clark’s rapt encounter with The Land of Cockaigne, Bruegel’s absurdist vision of the endpoint of appetite – ‘the “modern” personified’ becomes the figure who, having chomped his way through a great wall of porridge, ‘falls into paradise like a turd from an anus’. The sardonic swagger that runs through such passages makes them a joy to read. But what Clark terms a book of art history, others might term a jeremiad.

Heaven on Earth, however, means to prophesy against prophecy itself. The title indicates the target at which Clark wishes to take aim. This is the notion that some future transfiguration will redeem all the present injuries of our lives on this earth – a notion that may, Clark concedes, be ineradicable from human minds. For Giotto, Bruegel or Poussin, ‘heaven on earth’ would have had Christian lineaments; for Picasso looking back on the first half of the 20th century, its faces would have been ‘the classless society, the thousand years of the purified race’; whereas for newswatchers today – and this is why ‘the wonderful easy godlessness’ of French modernism no longer speaks to Clark – it takes the form of Islamist apocalypticism. Clark, an atheist appalled by the folly of all these transfigured tomorrows, acknowledges that his chosen painters may have consented to systems of belief, but looks for points at which their art seems to bend back against religious assent.

For to paint what’s beyond this world is always, potentially, to make it material, to bring it back down to earth. As Giotto’s Joachim sleeps on the hard, ‘resistant’ ground, an angel flares into visibility from the sky’s equally firm blue – crisp head, hands and wings propelled towards the dreamer as if by flickering flames – and Clark cherishes its hovering between gaseous and solid states. The supernatural has been seized in the very act ‘of becoming an image’ and thus rendered uncertain in status, in a manner that speaks to the modern doubter and all his inward ‘emptiness’. Clark’s Poussin salutes a Christian sacrament, yet in doing so also salutes the possibility of detaching from it and ‘standing alone in the world’, when he devises that figure of ‘bristling photons’. There is further restorative physicality to be found not only in Bruegel’s satire on dreams of consummate satisfaction, but in Veronese’s ‘heroic and pagan’ – yet also ‘tender and compassionate’ – view of the human. Clark’s study of the 1958 Fall of Icarus mural posits that Picasso adapted another famous Bruegel image so as to deflate – to bring down to earth – whatever lingering sense of epic catastrophe postwar Europe may have clung to as it looked back over the century. (This essay itself is peculiarly, drolly deflationary – too equivocal about the work’s qualities to entice anyone to Unesco’s Bâtiment des Conférences.)

Teasing his agenda of ‘earthboundness’ out of this disparate clutch of paintings, Clark devises an unfamiliar but incisive critical tool. He is led to think insistently about the ‘strange upright posture of the human body’ and the fact that most of us, artists included, ‘exist naturally and unthinkingly five or six feet off the floor’. Clark quotes Milton’s prayer – ‘What in me is dark,/Illumine: what is low, raise and support’ – and comments that while pictorial art seems ubiquitously concerned with its first clause, with issues of lighting, ‘very few painters seem to see that their art could occupy the second of Milton’s worlds just as naturally, putting the business of bodily raising and supporting up front.’ In the eyes of Clark’s ‘very few’, which here includes Bruegel, Veronese and Poussin (Goya goes unmentioned, but surely he is of the company), standing on our hind legs becomes ‘the key to our being in the world’. He argues that uprightness and its alternatives have endless resonances – ‘ethical, metaphysical, erotic’ – in the life of the species. And so this tough, springy and in many ways sparkling text not only offers us a take on the nature of pictures and deeply felt readings of some of the greatest pictorial imaginations, it also begins to set out an account of human nature.

At the same time, ‘odd’ does seem an appropriate word for the project. ‘Here I shall stay,’ Clark declares, once he has settled on that strip of the Poussin canvas, to which he devotes the remaining half of his essay. This left-hand margin is where his critical voice locates itself. The central area is where the customary business of the species may be expected to take place: marriage, miracle (Clark recognises that humans are suckers for the supernatural) and, moreover, murder (as his final essay reflects, humans are also hideously fond of killing one another). The materialist intellectual who stands at a distance from all this (‘the one of all the spectators, we are convinced, who looks hardest’) is in a position of awkwardness and, in a sense, of pathos. He wishes earthboundness on humanity. But humans tend to walk the earth with the head leading the way, and, as a result, for much of the time we are neither on nor of the ground. This airhead species uses language to articulate prayer and dreams of flight.

A serious disbeliever can’t but be haunted by his own exclusion from this: at one point Clark speaks of ‘there always being a non-person in the room’. But what can his alternative articulacy point towards? There is a kind of wistful devotion in Clark’s writing to some great, notional, unverbalised substance that lies forever beyond its grasp. It might be the sufferings of the immiserated: it might be the ‘vanished culture’ and the defiant comic ‘insolence’ of Europe’s 16th-century peasantry, about which ‘we shall never know much’ but which was lent expression by Bruegel when he painted Cockaigne. It might in fact be the business of painting itself.

Another task for the stander aside is to articulate more sharply the terms on which he separates from the others’ fantasising. Clark’s ‘coda’ argues that ‘heaven on earth’ rhetoric – the prospect of utopia – has too long weighed down the thinking of the left, a burden inherited from Christianity via the Enlightenment but one that it urgently needs to discard, both for reasons of political viability and of ontological economy: ‘There will be no future, I am saying, finally, without war, poverty, Malthusian panic, tyranny, cruelty, classes, dead time, and all the ills that flesh is heir to, because there will be no future; only a present in which the left … struggles to assemble the “material for a society” Nietzsche thought had vanished from the earth.’

It is a stirring peroration and one whose self-declared ‘pessimism’ and sober wisdom read all the more persuasively in the light of public events, seven years on from the essay’s initial appearance in New Left Review. If – once again – I call its direction of travel ‘odd’, it is because I feel that ‘For a Left with No Future’ is a kind of self-reproach aimed at the generation who grew up with Clark in the 1960s, rather than at alumni such as myself of the more downbeat decade that followed. Yes, those schooled on the emerging late 20th-century theme of ecological crisis have looked towards a future: but one that was dystopic, with no bright conclusion. Bad things were going to happen to an earth to which we were bound with a specificity that Clark’s politics do not begin to touch on. But that is the good of prophets, from Amos down to Johnny Rotten: to point to bad outcomes and by alerting us help us to mitigate them, even if only a little.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.