According to its account of itself, the New Hall Art Collection at Murray Edwards College in Cambridge is the ‘most significant’ collection of modern women’s art in Europe. There isn’t much competition: women-only art collections are rare things, outside Washington’s vast National Museum of Women in the Arts (five thousand artworks by a thousand artists, from Lavinia Fontana, b. Bologna, 1552, to Cindy Sherman, b. Glen Ridge, NJ, 1954). Murray Edwards isn’t a museum: it’s a women’s college, founded in 1954 – as New Hall – at a time when Cambridge had the lowest proportion of women undergraduates of any university in the UK.

When you visit Murray Edwards, the art on the walls isn’t the first thing you notice, rather it’s the walls themselves. The main college building – built in 1964 after the college outgrew its original home on Silver Street in a house rented from the Darwin family – is a brilliant work of Brutalist architecture, designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, who went on to build the Barbican. It’s all long concrete corridors, slender pillars and supposedly ‘feminine’ domes perched on top of flat roofs. The library is housed in what looks like a modern chapel (in this unusually secular college there is no actual chapel): it’s a sort of concrete Hawksmoor church, or a take on the Bevis Marks synagogue, with high windows and steep steps up to the gallery levels where the books are shelved. The main dining room, with utilitarian chairs and tables, sits under an enormous concrete dome. Smaller domes surmount three spiral staircases and a lift shaft at each of the four cardinal compass points in the corners of the room.

And then there’s the view from outside. The central courtyard is a paved patio surrounded on three sides by a narrow concrete-enclosed pool that curves around the circular fountain at the top end. Bright blue metal chairs sit jauntily on pale tiles. The dome of the dining hall rises above the scene. It’s both serene and surprising, like looking at a Brutalist mosque. From the Fellows’ Garden – the usual blossom and informal planting – you can peek at the reupholstered mid-century chairs and sofas and modernist patterned curtains inside. The floor is parquet and mid-century lamps hang from the ceiling. It feels more like a little piece of Pasadena than a site off the Huntingdon Road. In the Fellows’ Drawing Room, a Bridget Riley, Shadow Play, hangs casually on the wall behind the grand piano. It’s all unbelievably chic.

It takes a lot of work, and money, to keep the place looking this good. I visited on a day when the academics and the admin, kitchen and maintenance staff were having lunch together in the main dining room – one of the egalitarian things they like to do at Murray Edwards. I said to one of the maintenance men that the building looked in good condition. He laughed at me: would I like to borrow his glasses? He described the leaking roofs, the rotting wooden window frames in the student housing blocks that all need to be replaced with metal. He shook his head a lot. The college’s director of development told me about the time two of the domes slid off their perches: the concrete had worn out and they’d come unstuck; they had to be rebuilt and the remaining ones strengthened. I looked up at the massive dome overhead again – a little nervously this time.

It’s an extraordinary, assertive building, but also rather a severe one, with its long, intersecting corridors and rectilinear structures of concrete and grey brick. An unfriendly space, perhaps, without something to adorn the walls, and perhaps this is what inspired the college’s then president, Valerie Pearl, to write to a hundred leading woman artists in 1992 asking if they’d be willing to donate works to the college on the condition they’d be kept on permanent display. Three-quarters of them came up with the goods, starting off a collection that now contains more than five hundred artworks mostly by contemporary women, including Paula Rego, Fiona Banner, Tracey Emin, Judy Chicago, Mary Kelly and Cornelia Parker. It’s a refreshing feature of Murray Edwards that anyone is allowed in off the street to look around; the older, grander colleges like King’s and Trinity have porters who patrol like Rottweilers, evicting any would-be visitors from the college grounds before they’ve even managed to set foot inside a court, let alone an actual building.

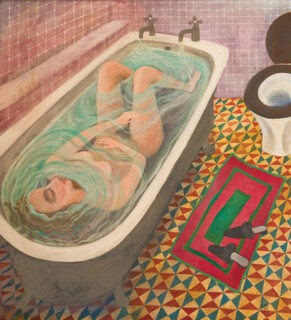

There are moments when the art collection and the building interact wonderfully well. Three giant bronze beetles, by Wendy Taylor, huddle at the bottom of a spiral staircase, encouraging you to look down at them and take in the perfect curve of the concrete at the same time. A Barbara Hepworth sculpture – Ascending Form (Gloria), on loan from the Hepworth Estate, a circle in an oval in a diamond – stands in the middle of a green courtyard, flanked by two pale brick student accommodation blocks. Rowena Comrie’s Capsize, an expressionist oil painting rising from yellow ground through reds to brightest blues, has found a prime spot above the SCR’s minimalist mantelpiece. In the dining room, a large Maggi Hambling canvas, Gulf Women Prepare for War (1986), showing women in chadors firing rocket-launchers in a dusty pink desert, hovers over the end of high table. Paula Rego’s response to it, Inês de Castro (2014), hangs alongside: King Pedro I of Portugal kneels before the exhumed body of his aristocratic Castilian lover, dressed in stately robes with a skull for a face. Gwen Raverat – a Cambridge institution, granddaughter of Darwin and friend of Virginia Woolf and Stanley Spencer – doesn’t suit all this drama, and the 18 Raverats that were bequeathed to the college, paintings and woodcuts of Grantchester and Newnham and a drawing of swans, are confined to a small meeting room off the entrance lobby. On the other hand, her granddaughter Lucy’s Dreaming in the Bath (1991) is situated next to the sign for the toilets and the gym.

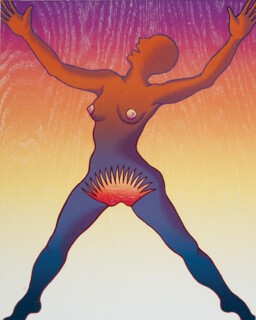

The collection has snowballed since the 1990s – almost unmanageably. The college has no funds set aside to pay for, and choose, works of art, so it relies exclusively on donations, most of them from the artists themselves. Hambling has said she didn’t really want to give them her Iran-Iraq war painting, but felt she had no choice after a delegation arrived at her studio and told her they’d like it. But even though the college doesn’t pay for artworks, money is involved: everything must be cared for, conserved, maintained and insured. In 2008 alumna Ros Smith and her husband, Steve Edwards, a pair of software entrepreneurs, gave the college £30 million. It’s the kind of money that buys your name above the door: it was at this point New Hall was renamed – Murray for its first president, the chemist Rosemary Murray, and Edwards for Cambridge’s biggest benefactor to date (not everyone was happy that the name immortalised was Smith’s husband’s). The bequest has mainly been spent on restoring the building and other initiatives. The current curator, Eliza Gluckman (her post is temporary, unless more funding can be secured), is concerned about the ethics: is it right to pay for the maintenance of the art collection or for acquisitions when there are student hardship grants to fund? There are other sensitivities to negotiate too. A collection of Judy Chicago lithographs, Voices from the Song of Songs, a group of 12 prints celebrating female sexuality, had to be moved from a meeting room at the request of a male tutor, who was worried they would unsettle anxious interviewees. But most of the time the art and the students get on quite nicely together. The bar has cheap beer and giant bean-bags to sit on, but it also has an iconic Guerrilla Girls poster beside a minimalist grid-like etching by Linda Karshan beside a drawing of a cigarette (‘This is not a cigarette’) by David Hockney, which not being by a woman, isn’t part of the official collection. The best galleries are the ones you can live and work in.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.