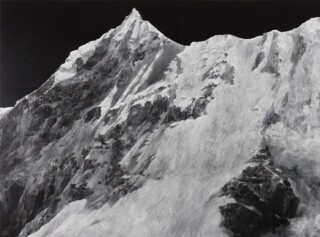

‘All the things I am attracted to are just about to disappear,’ Tacita Dean once told Marina Warner. Dean’s three almost simultaneous new shows – at the Royal Academy, the National Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery – are full of transient things: paintings of an ant moving across a rock; images of clouds, of decaying fruit; portraits on film of people who won’t be around much longer, or who have already died. Landscape, her exhibition at the newly expanded Royal Academy (until 12 August), begins with a scene of snow-covered mountains, The Montafon Letter, 12 feet high and 24 feet wide, done in chalk on nine blackboards joined together. Despite its scale and photorealistic detail, it looks dangerously erasable. It depicts an avalanche, arrested in motion: apparently at a moment in 1689 when, so the story goes, an avalanche in the Tyrol buried three hundred people. That was before a second avalanche buried the priest who went to administer the last rites and a third one unburied him.

Dean is a great collector of stories, except they’re often the same stories, obsessively returned to: stories of disappearance or hiding. Not making an appearance in any of these shows – none has exactly been a retrospective – are her films about Donald Crowhurst, who set off from Devon in 1968 in his trimaran Teignmouth Electron to circumnavigate the globe single-handed, but kept reporting false co-ordinates before disappearing and leaving his boat adrift. Those mesmerising, melancholy films were at the centre of an exhibition at Tate Britain nearly twenty years ago: two shot beside the rotating bulb of a lighthouse, one poring over the skeleton of the Teignmouth Electron itself, which Dean found bleached and overgrown on the island of Gran Cayman.

There is a much wider range of subjects in the new shows – the other two, which have just closed, were called Portrait and Still Life – but behind many of the works is the same habit of obsessive return. At the Royal Academy, Majesty is a three-metre-high photograph of a tree overpainted in white gouache: she meticulously traced round each branch and twig. As a subject, it has its origin in Dean’s practice of collecting old postcards from flea markets around the world: in Japan once, she says, she kept inexplicably coming across images of the forest of Fontainebleau, which led her to investigate the famous ancient oak there, which led her to read up about a 1400-year-old yew, now gone, in the village where she grew up, which led her to visit the three vast oaks in Fredville Park in Kent known as Stately, Beauty and Majesty. ‘I always need that tiny thread to get myself going,’ she once said. What gets her going is also a matter of chance or luck: Landscape includes a long glass case containing the collection of four, five, six, seven and nine-leaf clovers she began in childhood.

The centrepiece of the exhibition is a 56-minute film, Antigone, which explores the gap between Oedipus Rex and Oedipus at Colonus – Oedipus is blinded and banished from Thebes but yet to be led by his daughter/sister to the sacred grove. It is another story whose threads she has worried away at for years. ‘At art school in Falmouth,’ Dean writes in the catalogue, ‘I began inscribing and effacing the names Antigone and Oedipus with pencil then gesso on Bronco Toilet Tissue’ – ‘perhaps in art school imitation’ of Cy Twombly, ‘who seemed able, like none other, to awake his long-dead heroes by drawing their names’. (Twombly-like inscriptions keep appearing on her pictures: some incantatory or directorial – ‘darkness’, ‘rain’ – and some barely legible, like the chalk on chalk in The Montafon Letter.) Dean’s older sister is called Antigone, and she isn’t one to resist the spells cast by names – the blindness and companionship associated with her sister’s, the silence associated with her own. In the film, Antigone is played with great fierceness by Anne Carson, whose own obsession with Sophocles led to a poem, ‘TV Men: Antigone (Scripts 1 and 2)’, which is incorporated in the spoken text. Oedipus is played by Stephen Dillane, who limps across blasted landscapes – Bodmin Moor, Wyoming, Yellowstone National Park – in a long grey beard and dark goggles.

These interests, the limp too, are long-standing: at art school, for no reason she understood at the time, she took up drawing feet. One such drawing is included in the catalogue: it shows three deformed feet labelled as belonging to Oedipus (of the swollen foot), Byron (with his club foot) and ‘Bootsy’ (a family friend, and Antigone’s godfather, nicknamed for the special orthopaedic shoe he wore). Shortly before she left the Slade, Dean too started limping: the first sign (‘as if my mind knew back then ahead of my body’) of the progressive rheumatoid arthritis that now prevents her from straightening her right arm. Never wanting to make things easy for herself, Dean – who cuts all her film by hand, who campaigned to try to save the production of 16mm stock, who moved to Los Angeles to be close to the only labs in the world still equipped to preserve 16mm archive – took on extra handicaps to make Antigone. The film is shown on two screens (‘two eyes’ – left and right), so can never be played in a movie theatre. It was partly filmed in pursuit of the 2017 solar eclipse – the third time Dean has chased one on film – and was made by masking part of the camera’s aperture gate, then filming one scene, then rewinding to expose the previously masked part. This meant that the film was edited ‘inside the camera’: she couldn’t know what the montages would look like until the process was complete. She calls it ‘creative blindness’.

With its volcanic geysers, Theban courtroom and total eclipse of the sun, Antigone is an epic. If you immerse yourself in it, there are just too many connections and coincidences. Apart from Carson and Dillane, and Dean and her sister, one other person appears on screen: the publisher Peter Mayer, who reads aloud from a text by Dean – his voice gravelly, slightly hoarse. It so happens that Mayer used to be my boss: for about four years, I spent the best part of a week a month with him when he came to London, going to meetings with him, taking taxis with him between meetings, sitting in his smoke-filled office, listening to his stories; had he needed a crutch around town – a publishing Antigone – it would have been me. It also happens that Mayer died, at the age of 82, three days before the press view at the RA. But there he is on film, looking out at me over his glasses, waving his hand about excitedly as he reads – as he always used to.

Dean clearly has an affinity with old men. Her exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery was full of them. She visits the elderly Michael Hamburger at his Suffolk farmhouse with her movie camera, zooming in on the wonky doorways, the rotting window frames, the overgrown garden, the teetering piles of books – an old poet’s props. She watches as he inspects his apple orchard, the wind in the trees even louder than the whirr of the projector. The film is dim and desaturated. Hamburger talks about his apples, and about some pips Ted Hughes once gave him – ‘a kind of link between us’. In a different world, Merce Cunningham in his Bethune Street studio, performing – six times, on six separate screens – what could have been his final piece of dance: a rendering, in perfect stillness in his chair, of John Cage’s 4’33”. In LA, a craggy David Hockney sits in a chair surrounded by paintings he has made of other people sitting in chairs, in preparation for his own Royal Academy show. Shot from the side, he clutches his cigarette between his knuckles. Every now and then he flicks a clump of ash onto the floor; he bites his thumb, staring ahead. There is a moment of drama as he is about to flick the ash – but then changes his mind and takes another drag instead. And then, transformation: the camera moves round to the front, and Hockney bursts out laughing, his face now as vivid and alive as his mustard yellow shirt. He smiles, pushes his glasses back up his nose. ‘It’s very, very enjoyable, smoking,’ he says.

Filming up close, Dean seems almost to move into these men, watching for their tics, the way they inhabit their clothes. In her film of Twombly, intimately called Edwin Parker after his given names, her hero moves about his studio in Lexington, Virginia, inspecting sculptures and correspondence, eating lunch at a local restaurant, assisted by a mini-entourage of helpers. At one point, he fishes in the pocket of his tweed jacket for another pair of spectacles: he has the wrong pair in his hand, and you feel the clumsiness – the snag of a minor daily obstacle – as if you were doing the fishing yourself. Dean spent time with Twombly at his house in Gaeta too, and at the NPG fifty photographs from Gaeta lined the walls of the show’s central corridor. Her eye was caught by little objects resting in corners: a Sotheby’s catalogue, his loafers and – remembering that incident in Lexington – a pair of specs.

Dean isn’t afraid to honour the precursors – nearly all men – who have informed her work. Landscape, portrait, still life: all three are interesting to her, and she doesn’t believe in boundaries. Still Life, the show at the National Gallery, which included just four works of Dean’s own, was an exercise in curation that rested on unlikely coincidences, with a 16th-century Italian head of John the Baptist sitting next to Philip Guston’s 1976 Hat, its black backdrop superimposed with white lines – like chalk on blackboard. There were works by Chardin, Zurbarán, Sickert. She seems to like things in pairs: a pair of owls, a pair of plastic trays, a pair of hares, her own film of a pair of pears, dissolving in a jar of schnapps. A single painting by Paul Nash – Event on the Downs, a tree stump and a ball in a landscape with white cliffs behind – shows what an influence on her he has been: as early as the 1930s, he was experimenting with double exposure to produce genre-busting ghost photographs like Still Life on Car Roof. But it’s the portraits of old men I’ll most remember. It may be worth noting that Cunningham, Hamburger and Twombly each died shortly after Dean filmed them. This isn’t voodoo. It’s just her special instinct: she is always there to catch the thing before it vanishes.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.