Stare long enough into the void, Nietzsche writes in Beyond Good and Evil, and the void stares back at you. The trouble with nothing, no matter an artist or writer’s aspiration to the zero degree, is that it tends to reveal a residual something: whether a sensory trace of the effort at evacuation or a framing narrative about the very gesture of laconic refusal. In the case of the Hayward’s survey of half a century and more of invisible art (until 5 August), the void was filled in advance by a lot of tabloid mock-horror at the thought that a publicly funded gallery was about to charge £8 so that one could turn one’s gaze upon that vacancy, the air. The BBC ran a sneery piece on the Six O’Clock News. Actually, they phoned to ask if I’d comment, but my take on the show (which fittingly I hadn’t yet seen) must have sounded drearily accepting of its premise, because they never called back. The silence seemed right.

In truth, Invisible is both a bracing provocation – there really are empty rooms here, and notionally circumscribed gobbets of air to be wondered at – and a modestly meticulous story about the ways artists have found to approach, but perhaps never really achieve, complete invisibility. As Marina Warner wrote in the 5 July issue of the LRB, while reviewing Damien Hirst along the river at Tate Modern, the Hayward’s is an exhibition that courts attention above all else: attention to surfaces and atmospheres as much as, maybe more than, the works’ conceptual content. This last is all that such art’s detractors like to claim is going on, or not going on: the mere idea of emptiness left hovering, a grin without a cat.

The exhibition shuttles between the sublime idea of absolute nothing and the engaging reality of almost nothing. This oscillation has a prehistory, broached as much in certain artists’ attempts to articulate it verbally as in their near absconded works. Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) is the record of a month’s careful rubbing out and therefore not exactly a pure void, more a palimpsest in reverse – in Jasper Johns’s words, an ‘additive subtraction’. Such a work has also, of course, to live in a world that may fill it with meaning or form; John Cage had already observed of some white paintings of Rauschenberg’s that they were ‘landing strips’ for light and shadow. Cage, whose 4’33” is just the most notorious instance of an apparently silent work filled with inadvertent sound, liked to tell the story of visiting an anechoic chamber at Harvard, and in the absence of all other noise hearing the roar of his bloodstream and the electric whine of his nervous system. It’s more likely that he was experiencing mild tinnitus, but his insight holds: ‘What silence requires is that I go on talking.’

At the Hayward, this notion of a full or replete invisible art is introduced via Yves Klein, whose empty exhibition known as The Void seems uncompromisingly committed to vacancy, but also reveals how much aesthetic, even occult or spiritual content could be projected into a pallid abyss. Klein mounted four exhibitions deserving of that title, though he only attached the word ‘void’ to the third. For the first, at Galerie Colette Allendy in May 1957, he painted the whole interior white so as to create ‘an ambience, a genuine pictorial climate and, therefore, an invisible one’. In a brief snatch of film, Klein hams up the suggestion that paintings have fled, leaving only their aura. He frames with his hands the spaces they might have occupied, then sits on a radiator, looks around quizzically at the white walls and an empty vitrine, and walks off. The second version, staged the following year at Galerie Iris Clert on rue des Beaux-Arts, was a more provocative affair. Thousands thronged the street, and Klein happened on a young man playfully drawing on the freshly painted gallery wall; he called security and demanded: ‘Seize this man and throw him out, violently.’

The third void was installed, if that’s the word, at the Haus Lange Museum in Krefeld, Germany, where Klein’s small empty room may still be viewed by appointment. The fourth version returned to the conceit of disappearing artworks: the artist and friends removed all the paintings from one room for the Salon Comparaisons at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1962. Klein had by this stage devised an elaborate and alchemically inflected theory regarding ‘zones of immaterial pictorial sensibility’; he was willing to sell these zones, though he only accepted gold as payment. If the buyer – not quite a collector – agreed to burn the receipt, Klein would throw half the gold in the Seine. An art that seems at first all about nothing was as much concerned with value, exchange, material and transmutation.

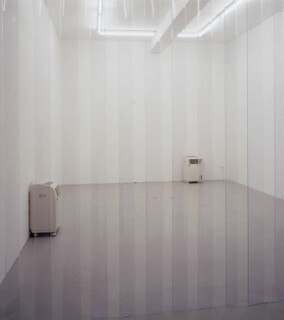

As the Hayward’s director (and the curator of Invisible) Ralph Rugoff points out in a suitably svelte catalogue (Hayward, £5), later artists have responded less to the mystical urges latent in Klein’s voids than to the institution-baiting gesture of stripping the gallery or museum of actual artworks. This is true for example of the conceptualist collective Art & Language, which in 1967 proposed (and in 1972 staged) The Air-Conditioning Show: an empty air-conditioned room accompanied by lengthy wall texts that explained the work’s ambition to create a ‘non-juicy’ or ‘ultra-usual’ space. And yet even here it is hard not to feel something more than is claimed by the austere intention. The forbidding Art & Language writings are not without texture and wit: ‘It has been customary to regard “exhibitions” as those situations where various objects are in discrete occupation of a room or site etc: perceptors appear, to peruse.’ Stray too close to one of two big floor-mounted air-conditioners and you’ll get a giddying blast of cold up your sleeve.

There are many such reminders of a minimal presence at odds with the vaunted immaterialisation of art in the conceptual era, and several of them have to do precisely with air. (Marcel Duchamp’s ampoule of Air de Paris is one reference point here, but Klein also made plans for an ‘air architecture’ composed of compressed-air ceilings and walls of fire.) Robert Barry’s Inert Gas Series (1969) consisted of documented releases of gas into the atmosphere; Tom Friedman’s Untitled (A Curse) is a plinth purportedly topped with a spherical portion of space cursed by a witch. Elsewhere, the media used to make the work had been assumed into the air, as in Bruno Jakob’s paintings made with snail trails or Zurich snow. There and not there, giving away very little but not quite nothing, such works seem like examples of Duchamp’s concept of the ‘infra-thin’, like mist on glass, or the warmth of a seat just vacated.

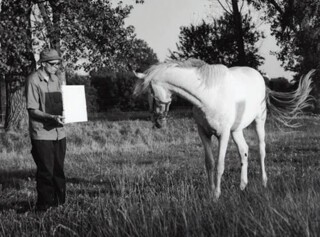

Samuel Beckett wrote in The Unnameable: ‘It is all very well to keep silence, but one has also to consider the kind of silence one keeps.’ They are all, it turns out, a little different, and none of them pure or (as Susan Sontag put it) raw. Among the artists in Invisible perhaps Andy Warhol, already a walking void of sorts, gets closest. In 1985, at the Area nightclub in New York, he stood briefly on a white plinth and then was photographed beside the ‘invisible sculpture’ that still retained some of his aura. The aura, that is, of an artist who was hardly there to begin with, and whose ambition was ‘the best American invention, to be able to disappear’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.