A master of impersonation, Cindy Sherman has served as her own model in her photographs since 1975, playing with familiar roles of female identity in series after series of inventive work. From the beginning she appeared almost too good to be true. Sherman was popular, first with other artists, gradually with the art world at large, eventually with a broad public; at the same time she could be seen as a postmodernist, for, along with peers in ‘appropriation art’ like Sherrie Levine, Barbara Kruger and Louise Lawler, she advanced a novel idea of the picture as a text of other pictures, in her case alluding to B-movie types and stock TV characters. Just as important, Sherman seemed to fit, hand in glove, with critical theory of the period: in her catalogue of women, feminists saw an exposé of stereotypes of femininity, and in her performance of roles, poststructuralists found an exemplum of the constructed nature of identity as well as an epitome of ‘the death of the author’ (no biographical person was disclosed in her photos). Her retrospective at MoMA in New York (until 11 June) suggests how right we were – and how wrong.

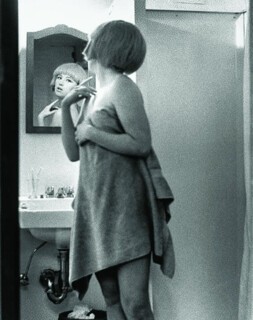

Even before her well-known Untitled Film Stills (none of which derives directly from actual movies), Sherman investigated the effects of gender expectations and fashion fantasies on young women: in one early sequence of images, her made-up subject passes from ambiguously male to super-femme; in another series, Sherman changes outfits so rapidly as to become her own hysterical Barbie doll. In this initial phase (from 1975 to 1982), in which she evokes generic formats like the magazine centrefold as well as the film still, Sherman presents the female subject under the gaze, the woman as a picture, which was also a principal topic of feminist work in appropriation art. Her subjects see, of course, but they are much more seen, and how they react to this capture by the gaze provides the drama in each image. Often this gaze seems to come from a subject off-camera, with whom the viewer might be implicated; sometimes it seems to come from the world at large; yet sometimes too it seems to come from within. Here Sherman shows her subjects to be self-surveyed, but in a mode less of narcissistic absorption than of psychological estrangement. Thus in the distance between made-up woman and her mirrored face in Untitled Film Still #2 (1977), Sherman points to the gap between the imagined and actual body-images that yawns within each of us, a gap that we attempt to fill with hopeful identifications with movie stars, athletes and other idols of the day.

In her next phase (from 1983 to 1990), the photos now in colour, Sherman draws on associations with fashion, art history, fairy tales and horror movies. The first two image-repertoires have long influenced self-fashionings, which Sherman parodies mercilessly: in her hands vanguard design produces fashion victims, and grand portraiture is given over to ugly aristocrats with scarred sacks for breasts and funky carbuncles for noses (here she riffs on celebrated paintings by Raphael, Caravaggio and Ingres, among others). This play turns perverse when, in some of her fashion photos, the subjects seem all but psychotic, with no ego awareness at all, and when, in some of the art history photos, the figures are little more than a patchwork of broken-down prostheses.

The turn to the grotesque is even more marked in the fairy-tale and horror pictures that follow, many of which show imagined freaks of nature (a young woman with a pig’s snout, a doll with the head of a dirty old man). Here horror means, first and foremost, horror of the maternal body, which is the primary site of ‘the abject’ as well, a liminal category defined by Julia Kristeva as neither subject nor object and thus charged with intense ambivalence. Sherman evokes this extreme state in scenes suffused with signifiers of menstrual blood and sexual discharge, vomit and shit. The domain of her so-called civil war and sex pictures of the 1990s is also abject, punctuated respectively by close-ups of simulated damaged or dead bodies and sexual or excretory organs. The vagina, Lou Andreas-Salomé once wrote, is ‘taken on lease’ from the rectum; in some pictures Sherman conflates these orifices in obscene ways, adding the odd penis as well. In other images the subject is so disarranged, so overwhelmed by her awful surroundings, as to disappear altogether.

‘Abject art’ addressed a very grim period in the US. Ravaged by the Aids epidemic, the art world in the 1990s was indeed steeped in a ‘civil war’ with political leaders over ‘sex’, as Sherman suggested with her series titles. Then there was the neoliberal attack on the social contract at large, which Clinton waged with only slightly less relish than Reagan. Who could have imagined things would get worse under George W. Bush? During his regime, however, Sherman pulled back from horrific images and, now in her fifties, focused on portraits of middle age, a period of relative neglect in mass-cultural representations of femininity. At first she made images of lower-income women struggling to meet the cultural demands of sex appeal, with expressions ranging from the desperate to the defiant. Then she moved on to nouveau-riche ladies decked out in ostentatious gowns and jewels. More burned than tanned, and stretched to the point where the cracks surface again, these women look as if they have scratched their way to the top, only to confront there the inevitable fall to gravity, age and mortality. These pictures, which came to be known as the Hollywood/ Hamptons series, preoccupied Sherman during the 2000s, but she also produced a complementary series, a group of clowns made up so excessively as to appear more crazy-scary than funny-sad. In the conservative art of the 1920s, after the radical experiments of Expressionism, Cubism and Dada, clowns, harlequins and the like began to appear – in the work of Picasso, Beckmann and others – as ciphers of the melancholic artist resigned to the status of court jester to the rich and the reactionary. Sherman too puts on a clownish face, but her clowns have bite.

The exhibition keeps some series intact and mixes others together. The effect is to show that the work is more heterogeneous than we often think. The ingénues in the early pictures are not simply the victims of imposed roles, as some of us wrote at the time. These are scenes less of ideological interpellation from the outside than aspirational identification from within: the young women struggle to approximate the scripted types, not to escape from them. In some way this makes the work more feminist than feminist critics believed, because it suggests how we import alien identities into our selves: ‘If only I could get my hair right, clear up my skin, buy the right blouse, I could be me.’

Another insight has to do with biography, which Sherman had seemed to negate. It is not just that, as the series roll by, we glimpse the artist age behind all the make-up; it is that the arc of her subjects from ingénue to dame is not unlike that of her own life – from the young artist new to the city to a cultural figure in her own right. The images also trace this trajectory in their production, from small black and white faux film stills (galleries were modest then too) to large colour pictures produced digitally on the scale of paintings (Sherman has spoken of her wish to compete with the grand installations of some of her male colleagues). In this social story there is also a political allegory: those of us who started out as the postmodernist generation, eager to build on the advances of the 1960s and 1970s in art, theory and other domains, had that future hijacked by a reactionary turn in almost all things. That painful narrative can also be read here.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.