As he neared the end of a recent diatribe against President Bush for plotting war secretly, and in defiance of the US Constitution, the American journalist Anthony Lewis felt impelled to add: ‘None of this argues that George Bush is a bad man. He is not.’

Years ago Roland Barthes wrote about the bourgeois propensity to think in essences, and nowhere is this more evident than in the way Americans think and write about their political leaders. It was not as if Lewis needed the after-thought about Bush’s non-badness, His column would have ended perfectly well without it. But the need to reassure both himself and his readers was overwhelming and thus, after solemn censure, the President was sent on his way with his essential non-badness duly guaranteed.

‘Essential Bush’ is not, in fact, alluring. There’s always been a fairly broad streak of impulsive petulance in him. In any sort of tight spot his voice tightens up into a waspy whine. He reacts badly to criticism or challenge, like a man who feels a carefully constructed self-image is under improper duress. Essentialists can search for continuity of political belief in the man, some backbone of principle stiffening his curriculum vitae, but such investigation, if conducted with any degree of realism, is not encouraging, and discloses a kind of Flashmanesque moral seediness, particularly in his CIA/Contragate incarnations and his fascination with rogues. He has countenanced some very bad things in his time.

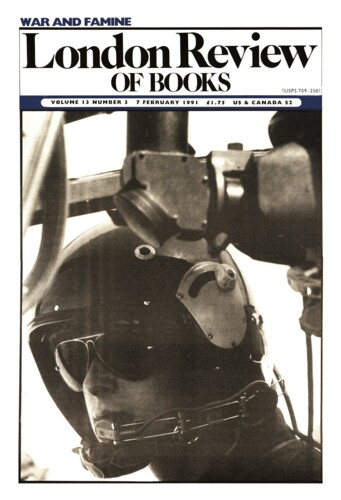

In these days of Desert Storm Bush is on display as commander-in-chief and man of calm resolve, just as five months ago he was the master diplomatist pledging only ‘defensive’ forces to Saudi Arabia. He’s slid from the latter stance to the former, not because of strong and purposeful leadership, but because of political cowardice, since the road to a peaceful settlement – simultaneous linkage of Iraqi withdrawal to a Middle East conference and so forth – would have required courage of the sort almost invisible in American political life. After all, the fact that people are fighting, killing and dying in and around the Gulf is the consequence of cowardly political leadership stretching over years. The hateful figure of Saddam Hussein emerged as one of hope for many Arabs in part because of the failure of the United States to address in any determined way the aspirations of the Palestinians.

One can delve down and down through Bush’s intellectual and spiritual architecture without hitting anything particularly solid. I remember interviewing members of his family back in the late Seventies when he was running for the Republican Presidential nomination, and coming more than once on wonderment at the thought that Poppy was running, mixed with utter bewilderment about his belief in anything beyond doing something tentatively described as the right thing. A decade later, when he was once again running for the Presidency, I began getting letters from a veteran who had been tail-gunner in a bomber in the Pacific during the Second World War. He’s collected and compared various accounts made by Bush or his publicists about his best-known misadventure as a pilot in the South Pacific, when his plane was hit by Japanese flak and he bailed out and was eventually rescued by submarine. These accounts did indeed vary, though all agreed that after Bush bailed out his plane, carrying two crew members, crashed into the sea and they both were killed. It wasn’t long before I lit on the account of a man who’d been in the plane immediately behind on the same bombing run. He’d seen the plane list and asked his pilot to chop back to take a closer look. Then, and years later, he maintained that the engine was not on fire, and that Bush could have almost certainly crash-landed the plane in the sea. In this man’s view, Bush appears to have popped open the cockpit hood and jumped out as soon as the plane was hit.

It wasn’t the sort of story that journalists, in general agreement that Bush was essentially non-bad, were interested in discussing, and though I wrote it up in a column just before the 1990 Election no one paid any attention, though if true – and it seemed to me pretty certain that it was – the episode did provide useful insight into the man who, in the 1988 campaign, was trading on his war record, courtesy of an amateur movie of his rescue from the Pacific shot by one of the submarine’s crew members.

I’d fallen prey to the illusion that Bush was vulnerable to something journalistically classified as a ‘damaging story’. Nixon was always reeling – eventually out of the Presidency – under the impact of these ‘damaging stories’ because a powerful segment of the press hated him enough from time to time – though not during the Christmas bombing of Hanoi, to be sure – to make a great hullaballoo whenever a damaging story surfaced. Journalists, none more than Lewis, had decided that Nixon was essentially non-good. After he was gone, the illusion, held by others as well as myself, persisted for a time that ‘damaging stories’ would go on making a difference. I was writing a political column with James Ridgeway at the time, and when Jimmy Carter’s fortunes began to rise in the 1976 campaign we had a researcher work through documentary records in the Georgia State archives, amassed during his stint as Governor. Our man toiled diligently away – so diligently in fact that we concluded he was also in the employ of the Republican National Committee – and soon unearthed materials disclosing impressive amounts on non-goodness in the conduct of Governor Carter, who at that time was promising to inaugurate a new age of virtue in American public life, raising essentialism – his goodness, reflective of the goodness of all Americans except his opponent – to an altitude unprecedented in campaign rhetoric.

It was plain enough, from the testimony of the archives, that Carter was just as much a liar, double-dealer, blowhard, serf of corporate power, and coward, as your average seeker after high office, and we hastened to publish the evidence. It made no difference, given the consensus on his non-badness, and I realised then that the ‘damaging story’ was a thing of the past, part of the discarded paraphernalia of the Nixon age.

Reagan answered most satisfactorily this essentialist expectation, since as an excellent actor he had no problem in assuming or discarding roles, and could constantly refashion the ‘essential Reagan’ and live each new role with utter inner conviction.

The first time I saw him in the flesh I thought immediately that ‘flesh’ seemed too intimate a word for the tissue he was then presenting, in 1976, as the visage of a man younger than his years. The ‘age factor’ was thought to be a problem. During the press conference in the New York Hilton in which this ‘age factor’ was delicately raised he invited us to come up and look at his hair, give it a tug if necessary, make sure it wasn’t tinted dark by Grecian formula. As I gave his hair a dutiful yank he held his head forward with a detachment so docile that it was clear that here was a man of iron resolve, every resource recruited to the business of being Reagan-as-young-man-with-dark-hair.

The last time I saw him, with Nancy at the Republican Convention in New Orleans in 1988, flesh was no longer a word one could even toy with, as I gazed at his impassive lizard-like countenance. The President’s body sat there, not at all like a human frame reposing in the moments before public oratory, but as Reagan-at-rest extruding not a tincture of emotion until impelled by some unseen spasm of synapses into Reagan-amused, the briefest of smiles soon being dismissed in favour of the sombre passivity one associates with the shrouded figure in some newly-opened tomb before oxygen commences its mission of decay.

Nancy as loyal wife complemented the bogus arc of her husband’s career, now arrived at its political terminus underneath the Super-dome. By the early Forties, when he first met Nancy and when young Poppy was still at Yale, preparatory to shipping out to the Pacific and his appointment with the cameraman on the submarine, the studio publicity department was already turning Ronald Reagan into a war hero.

By day he would work in ‘Fort Wacky’ in Culver City, where they made military training films. Experts would take old stock footage of Japan and then edit it as though viewed through a gunsight. This not only helped gunners in planes about to make sorties over Japan but was also used in ‘live-action’ newsreels for American audiences craving combat footage. Things were more sophisticated back then: these days we have to be content with a CNN man holding a microphone out the window to hear the bombs drop on Baghdad, as he extols the pin-point accuracy of the US bombers while CNN displays on the screen a photograph of downtown Baghdad, thus fostering illusions once more about the effectiveness of air power. The fanzines discussed the loneliness of Reagan’s first wife Jane Wyman, her absent man off at the war (a few miles away in Fort Wacky, home in time for supper) and his hatred of the foe. ‘She’d seen Ronnie’s sick face,’ Modern Screen reported in 1942, ‘bent over a picture of the small swollen bodies of children starved to death in Poland, “This,” said the war-hating Reagan between set lips, “would make it a pleasure to kill.” ’

In his Oval Office speech launching Operation Desert Storm President Bush didn’t say it would be a pleasure to kill but gave the overall impression that it would be a joy to kick Iraqi ass, and he brandished rhetorically the latter-day equivalent of those photographs of Polish children – namely, the ‘innocent children’, as he described them in his address, suffering in Kuwait.

He was most probably referring to his favoured symbol of Iraqi vileness, the babies supposedly left to die in Kuwaiti hospitals by Iraqi troops looting their incubators for shipment back to Baghdad. It turns out that baby-from-incubator mass murder – over three hundred in the early versions – is entirely untrue, as I discovered recently from Aziz Abu Hamad, a Saudi consultant researching the matter for the New York-based human rights organisation Middle East Watch. The story had been given the imprimatur of a December report by Amnesty International which swallowed whole the account (which he soon began to emend) of a Red Crescent doctor in the employ of the Kuwaiti government-in-exile and lodged in the Sheraton Hotel in Taif’ as an employee of that government. After extensive investigation Aziz concluded there was no credible eyewitness or testimony to sustain the charges of mass baby murder. Bush apparently fortified his resolve in the pre-war hours by reading the Amnesty report with set lips, before attending divine service conducted by the Rev. Billy Graham who, in former non-good old days, urged Nixon to bomb the dikes in North Vietnam.

Forty years after he gazed at those photographs of Polish children Reagan would tell Yitzhak Shamir, then foreign minister of Israel, that he had helped liberate Auschwitz in Poland, and had returned to Hollywood with film of the ghastly scenes he had witnessed, and if in later years anyone around the Reagan dinner table controverted the reality of the Holocaust (apparently a conversational staple at such repasts) Reagan, so he would tell Shamir and others, would roll the footage till the doubts were stilled. Of course Reagan never left Fort Wacky and in due course his false account to Shamir became known. But the exposure of these demented fictions of his never made the slightest difference to the esteem in which he was generally held by the press.

Essentially ‘good’, and hailed as such, even as he cut school lunch programmes and Federal housing subsidies, Reagan could survive any damaging story, outsmile the exposure of any lie, and An American Life is just one more episode in this mendacious odyssey. The new act is a golly-gee account of how a small-town boy got to the White House, saved America from economic ruin and founded a new era of world peace.

It’s eerie to read this stuff now: like looking at the silent movies of Reagan’s childhood. The acting styles have already changed, the props look out of date. Gone from us only two years, Reagan already seems as remote in time as Harding or Coolidge, and the vainglory of his renewed America and his new world era seems as tinny as a silent-movie piano amid the rumbling disasters of the new decade where non-badness is having its violent rendezvous with Evil.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.