One afternoon last year I walked up a steep incline from Applecross Basin on the Forth and Clyde Canal, stopped under the second pylon I came to and looked out over the monochrome skyscape. I had been told that this was the spot where Duncan Thaw, the protagonist of Books One and Two of Alasdair Gray’s Lanark, utters his most famous lines. ‘If a city hasn’t been used by an artist, not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively,’ he says, when his friend Kenneth McAlpin wonders why no one ever notices Glasgow’s magnificence.

The spot by the second pylon was on Gray’s regular beat. In the 1960s, he lived close to the Glasgow School of Art, where he trained in stained glass and mural-making, and he often walked along the canal, past Sighthill, Pinkston and Port Dundas, gathering up its sooty buildings and besuited young bucks as material for his paintings and murals. By the end of the decade, the M8 had slashed through the city, rendering much of it unrecognisable. The only building left from the Port Dundas/Applecross section of Gray’s best-known oil painting, Cowcaddens Streetscape in the Fifties (1964), is a seven-storey brick monolith called the Whisky Bond. Look closely at the right-hand top corner of the picture, and you can see it peeking out from behind a row of grey warehouses, a single daub of red beneath leering black clouds. The Whisky Bond is now home to the Alasdair Gray Archive, a heroic attempt to preserve his legacy.

The curator, Sorcha Dallas, first met Gray in 2007, when his literary reputation exceeded his artistic one, and she was growing disillusioned with her work as a commercial gallerist. She understood his dishevelment and quixotic behaviour as a product of creative monomania. She represented him for the next eight years, curating a major retrospective of his art at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in 2014. A fall at home a few months after the show ended left Gray confined to a wheelchair and unable to paint (though he went on to finish his translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy).

When Gray died in December 2019, Dallas was given three months to clear his West End flat of all its books, artworks, manuscripts and letters. The flat, which had belonged to his second wife, Morag, who died in 2014, had been both his living and working quarters (Morag made herself scarce most days to give him space to paint and write). Dallas remembers it as a restless place, where interesting people – assistants, fellow artists, friends – drifted in and out.

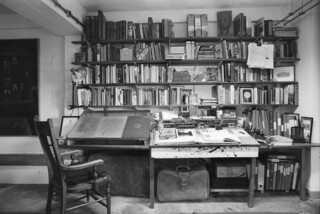

She wanted to create something that honoured Gray’s quirky personality and practice. And so, when you enter the archive, you find yourself in a living room dotted with motley furniture. To your left there’s the two-legged desk Gray found in a back lane and had drilled into the wall for stability. To your right there’s a table overflowing with paint pots and palettes and brushes and spray mount. On the wall, an octagonal tabletop has been transformed into a luminous artwork. And in the centre of the room there’s the green chair on which many models sat in thrall to its owner’s monologues, and which appears – as a throne – in his mural of the Book of Ruth in an East Renfrewshire church. On the two-legged desk is a photograph of a young Alasdair – Billy Bunter in a beret – with his sister, Mora; a chicken bone, inscribed with the date of the chicken’s consumption; a handful of pens in an old prunes can; and a selection of his books. There is a fuller library, laid out exactly as it was in his flat, in the room next door.

‘When Alasdair has been concentrating on work and is given a good opportunity to speak about it, listening to him is like opening up his brain and watching the contents spill gloriously onto the table,’ Rodge Glass – who worked as Gray’s assistant when he was in his twenties – wrote in Alasdair Gray: A Secretary’s Biography (2008). There is a similar effect here. On the day I visited, Dallas showed me a box containing the original illustrations from Every Short Story (2012). They tumbled out like a William Blake vision: boggle-eyed angler fish, flying horses, crying demons, brain babies, Amazonian women, scenes of bacchanalia: a smorgasbord of grotesquerie. In another box, I discovered an exquisite book called ‘Morag’s Museum’, which Gray made for their wedding anniversary, and a love letter, written to his tipsy, snoring wife, that could have been sent by James Joyce to Nora. In it, Gray describes his attempts to wake Morag by stroking her brow and patting her cheeks, before leaving her to sleep, while he heads to the pub to get similarly intoxicated.

There is nothing so sacred you are not allowed to touch it. You can hold in your hand a seashell Gray picked up on a trip to Fairlie beach with some friends on 7 February 1994. You can pull out a book at random, open it at a marked page and read, scrawled in the margin, Gray’s reaction: ‘middle-class nonsense!’ Dallas told me he would sometimes return to previous marginalia and argue with his former self. There are books from his childhood – the Harmsworth Encyclopedia, for example – in which the mythological and the real mingle so closely it is difficult to tell them apart. Sometimes visitors recognise a book they lent to him. They can thumb through it, but they don’t get to take it home. When the poet Liz Lochhead visited, she noticed a battered anthology of George Bernard Shaw’s plays she used to read when she was round at his flat; she asked to do a pencil rubbing of the embossed portrait of Shaw on its cover as a memento.

One of the most extraordinary objects in the archive is a ledger that sits on the two-legged desk. Rescued from a skip in the 1960s, it had been only partly filled in. Gray worked around and sometimes pasted over the columns of income and expenditure, often integrating the existing text with his own words and pictures. The ledger contains preliminary sketches for Cowcaddens (a copy of which is propped against an adjoining wall), along with black and white photographs of a vanishing Glasgow. The window at the archive looks out towards the spot where Thaw gave his speech, while the sketches include some long-gone buildings: rows of tenements and the old school where the Whisky Bond car park now stands. If you look from the ledger to the painting to the window quickly enough, you can watch – as if through a zoetrope – the landscape flicker and change.

In the mid-2000s Gray’s visual work was still neglected, undermined by its ephemerality (his murals around the city were often just one step ahead of the wrecking ball); its ubiquity (he would draw pen portraits for almost anyone who asked); and what some saw as his ‘parochialism’. When Dallas first offered to help Gray hang an exhibition, she turned up to find him in the basement of a café-cum-gallery with a shonky stepladder and an old hammer. Since the retrospective in 2014, however, Gray’s work has been shown at the Tate, the auction price of his best pieces has more than doubled and Glasgow Life (the organisation that runs the city’s museums) has purchased Cowcaddens for the Kelvingrove gallery.

Gray’s masterpiece is the celestial ceiling mural at Òran Mór – a church in the West End converted into a restaurant/ music venue – which he began painting in 2003. The original church beams divide the ceiling into twelve areas and Gray painted a constellation of the zodiac in each. As well as the ceiling fresco, there are marble balustrades, painted columns, mirror panels and portraits of staff members who worked at Òran Mór over the years. It is the largest free-to-view artwork in Scotland.

Yet, despite the revival of interest in Gray’s visual work, Dallas struggles to keep the archive afloat. The Scottish government paid the first two years’ rent at the Whisky Bond, and there have been successful collaborations with other organisations – most recently the Glasgow International Comedy Festival, which commissioned three writers to create pieces inspired by Gray’s work. But the archive has no core funding and Dallas doesn’t receive a salary. She is determined to keep her weekly tours free, but relies on visitors who can afford it to make a donation.

When Gray died everyone seemed to have an anecdote. I heard one about a book reading during which a bee landed on his face and began making its way towards his nostril. He didn’t try to brush it away, but instead declaimed: ‘I seem to have a BEE on ME.’ Glass told a story about how Gray – not au fait with technology – once Tipp-Exed out a word on his computer screen. Gray was the first person I ever interviewed. In 1985, at the age of seventeen, I perched in the bedroom of his earlier flat in Kersland Street (which he shared with his first wife, Inge) and fired off a series of inane questions that I can no longer remember. There are photographs of that flat on a wall at the archive: brooms and dustpans hung up like art exhibits in his kitchen, manuscripts scattered across the bed and, of course, his green chair. Was Gray sitting in it when I switched on my tape recorder? Visitors bring their stories to the archives and sometimes more. Recent donations have included a pile of letters from Gray’s former cleaner, some books dedicated to his childhood friend Katy Gardiner and documents relating to his unhappy stint as professor of creative writing at Glasgow and Strathclyde universities.

Gray spent his life collaborating with and advocating for other writers, among them Bernard MacLaverty, Tom Leonard, James Kelman and Lochhead. One of those he championed was Agnes Owens, whom he called ‘the most unfairly neglected of all living Scottish authors’. Dallas is building up an Owens archive in the room next door which she hopes will open to the public later this year. She saves what she can, but it’s often too late: take The Falls of Clyde, which Gray painted in the Kirkfieldbank Tavern near Lanark in 1969. It was papered over and forgotten until being rediscovered in 2006. Gray restored it over ten days in 2009, but when the pub was sold to a developer in 2020 and turned into a block of flats, the mural was destroyed.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.