To celebrate the first week of their marriage, Wafiq decided to cook lunch for his wife. He fried eggs on his brand-new stove while Rana arranged the dishes. Wafiq and Rana got married in the last week of October, and moved into the apartment. Thanks to the war, they decided not to have a wedding party, or even a family dinner.

Wafiq was proud of his new apartment, in the village of Maaysrah, north of Beirut. For two decades, since he was sixteen, he had worked in menial jobs – in a petrol station, on construction sites, at a grocer’s – until he graduated from university with distinction and began teaching at the local French lycée. Each month he spent only a fraction of his modest salary, entrusting the rest to his mother. When he had saved enough he started building a new floor on top of his father’s house. First, the concrete columns, standing alone for a couple of years with steel bars protruding from the top. Then he had saved enough to build a roof, and the work progressed slowly from there – plumbing one year, electrics the next. Finally, last year, he took out a loan, spread over seventeen years, to furnish the apartment: a bedroom, a small living room and an ‘American-style’ kitchen with a centrepiece he designed himself – a steel and marble island bar.

Downstairs, Wafiq’s mother and father were having coffee with some neighbours. Abdullah Amro was a well-known village elder, and people often visited him to seek advice on family and financial matters, or to ask him to mediate in feuds. Usually he received visitors in the diwan, a reception room attached to the main house. Looking out on a garden of pomegranate and olive trees, with a view of the Mediterranean beyond, it was a favourite meeting place in the village. But after the Israeli attacks began in late September, every inch of the house and diwan was filled with relatives who had fled their homes in southern Beirut and South Lebanon to take shelter in Abdullah’s house, so the gathering was taking place on the balcony instead.

Wafiq’s sister, Sayda, her husband, Jaafar, and their two teenage children were camping on the ground floor, along with Jaafar’s brother, his wife, her mother and five more children. The two families had fled their homes in the southern city of Tyre after the Israeli military issued evacuation orders. On the floor above was Wafiq’s brother, Muhammad, a teacher at the state technical college, with his wife and children, as well as a distant relative, Rassmiya, and her children. Displaced twice, Rassmiya had fled with her family from their village in the south, first taking refuge in the Msaytbeh neighbourhood of Beirut. But after an Israeli airstrike there killed two dozen people and reduced several buildings to rubble, she decided that Beirut wasn’t safe.

The people living in the house tried to maintain a normal routine as they obsessively followed the news, tracking airstrikes on their home towns and villages, taking in reports of the injured and dead. Everyone’s life was on hold. Jaafar had put his PhD thesis on a hard drive, hoping he could continue his online studies at an Iranian university, but he couldn’t find the focus or the time. Instead, he was working with his brother to collect aid and donations. His son, Hadi, was helping out in the local café, where he passed the days serving espressos and narghiles to the villagers – most of them his cousins. Sayda was busy all day. A psychiatrist with the Islamic Health Authority, she had set up a team of volunteers, co-ordinating with Lebanese NGOs to provide assistance at shelters. At night, rather than sleep in one of the bedrooms with the other women, she laid out her bedding beside her husband in the corridor.

Below the house, on a bend in the road, Hadi stood at the entrance to the café and waved to his cousin Ali on the balcony, beckoning him to come down. He had just walked back into the shop when he heard a loud screech overhead. A second screech followed, and then an explosion. When he scrambled back outside, instead of the balcony where Ali had been, he saw a massive ball of white smoke rolling into the sky.

Wafiq had drained some potatoes into a sieve in the sink, turned off the gas on the stove and was turning toward his wife when he saw a flash of light. Then something strange happened. He watched the floor under his feet crack open and collapse. Instinctively, he pushed his wife under the marble bar as they fell.

Hadi began running up the hill through the smoke and ash. The house was gone: a smouldering mound of rubble lay in its place. The explosion had stripped the trees of their leaves. He saw a man sitting on the ground, dazed and staring at his shredded legs. His face was covered in dust and blood, but Hadi recognised Abdullah from the strips of clothing hanging off him. Hadi couldn’t do much to help his grandfather, so he left him and rushed towards the ruins of the house, making his way through twisted metal and lumps of concrete. He climbed over what was left of the roof and started digging out masonry.

Jaafar and his brother were driving back from the coast, where they had gone to buy supplies for the café, when they spotted a column of white smoke. A few minutes later, a voice message from Hadi arrived in the family WhatsApp group: ‘They hit the building … they’re all gone … they’re all under the rubble.’

Beneath the collapsed roof, Wafiq was lying in foetal position. He tried to move, but his body was wedged between the stove and the fridge, which had fallen on his right arm. He called out to his wife and she called back: she was safe, she said, under the marble island. He told her to stay calm, preserve her energy and to keep talking to him. Inside, he was panicking, struggling to breathe and to cope with the pain in his arm. Like all teachers, he had been required to take a first aid course when the war broke out, and one sentence lingered in his mind: ‘Don’t close your eyes.’ He could hear people digging above, so he started shouting ‘Ya Mahdi, ya Zahra’ – a Shia call to the redeemer, and to the wife of Imam Ali.

Hadi found a body, one of the neighbours who had been having coffee with his grandparents, and continued to dig until the medics arrived and pulled him out, pointing at his bleeding feet. He hadn’t noticed that he had been barefoot all this time.

The body of Sara, Hadi’s sister, who had just enrolled at university to study graphic design, was the first to be found. Wrapped in a blanket, it was carried by ambulance to the morgue of a nearby hospital. Jaafar stayed behind at the scene, waiting to see if his wife was still alive. He kept hoping – even when they pulled out the bodies of Rassmiya and her five children, who had arrived at the house only two days earlier, and even when the bodies of his brother’s family were taken away.

Wafiq, still trapped, could hear people digging above, but suddenly thought: what if he hadn’t turned off the gas? What if one of the rescuers was smoking? Would there be another explosion? He was terrified about his wife. ‘Ya Hussein, ya Hussein,’ he kept calling until he finally saw the beam of a flashlight. Rana was rescued first; he had to wait another two hours. By then, he had lost all feeling in his arm and was sure it would have to be amputated.

Two days later , I went to Maaysrah. From the coast, the winding road threads its way up through terraces of pine and olive trees. Modern villas mingle with Ottoman-era houses, overlooking the valley of the Ibrahim river to the north and the sea to the west.

Maaysrah is one of two Shia villages in the otherwise Christian region of Keserwan in Mount Lebanon. The Shia of Keserwan were expelled by the Sunni Mamluks in the 13th century from the strategic mountain slopes close to the coastal plains, but then in the 18th century the Shia Amro clan were granted lands here following a feud with another clan elsewhere in the mountains. The community thrived on silkworm farming and olive oil production. At the entrance to the village is a large Christian monastery; higher up is a mosque topped by a golden aluminium dome, built to honour an eminent local jurist known for his ecumenical writings. The yellow flags of Hizbullah fly from electricity poles as a sign of defiance in a time of war, while a few old stone crosses stand among the trees and shrubs.

At the site of the strike Hadi was hobbling along on crutches, with bandages on his feet. Wafiq, who was with him, had miraculously escaped with only scratches and bruises. With the help of a municipal worker, he was searching for any human remains still buried under the rubble. They came to a spot where a swarm of flies had gathered. Hadi began throwing aside broken masonry. He picked out shreds of fabric and blackened flesh, putting them in a plastic shopping bag to be buried later according to religious custom. Wafiq walked around the ruins of his family house. A few flashes of colour broke the monotony of the grey debris: the orange of a bedsheet, the blue of flattened plastic jerrycans, the green of a book cover, and the red of a shirt tangled in a web of steel bars, the flotsam of the multiple generations who had lived here.

He pointed at where he thought he had been buried, explaining the layout of his kitchen. ‘Israel has not only killed my parents and relatives,’ he said. ‘They also took away all our childhood and happy memories when they destroyed our home. My mother was a frail old woman. For eleven months she repeated that she could only ask god to reward her with martyrdom like the people of Gaza. I would say how? She wasn’t going to become a fighter at her age. But the Israelis fulfilled her wishes.’

Jaafar and other relatives were sitting on white plastic chairs in the garden of a nearby house. Jaafar said they hadn’t yet buried his wife. They were still waiting for DNA results to identify her remains. ‘We have seen a lot as a family,’ he said. ‘Death is not a stranger in our house.’ He told me that he and his siblings had grown up in the holy Shia city of Najaf in Iraq, where their father, a cleric from South Lebanon, had gone to pursue his religious studies. Like hundreds of other foreign students he studied jurisprudence and theology under the guidance of Najaf’s leading Shia scholars, following centuries-old traditions. Some of the students were attracted to a new brand of revivalist, revolutionary discourse. This was considered anathema by the traditionalists, who maintained that the clergy should confine itself to religious guidance, jurisprudence and the collecting of tithes. The quietist view held that it was forbidden for the clergy to set up or be involved in a government, since temporal rule was inherently illegitimate until the return of the Imam al-Mahdi. The revolutionary clerics, by contrast, led by Ayatollah Khomeini and Iraq’s Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr and influenced by both leftist thinkers and the ideologues of the Muslim Brotherhood, advocated a Shia Islam that would take an activist role in political and social affairs. The clergy should seek to implement Islamic governance across all aspects of life as the only way to achieve justice for the oppressed masses, and to lead the Islamic Ummah in the struggle against Western imperialism, Zionism and communism.

For these clerics the martyrdom of Hussein, the grandson of the prophet and third imam, wasn’t merely a tale of suffering and lamentation but a cornerstone of Shia historical memory: a narrative of resistance that stretched from the plains of Karbala to the modern-day fight against Israel and its Western allies. Many of their students, including those who in the early 1980s would found Hizbullah, were deeply committed to that history of resistance. In Iran under the shah and in Iraq under Saddam Hussein, calls for Islamic revolution were met with fierce repression. Jaafar’s father survived the Baath Party’s purges of the Shia clergy in the late 1970s and 1980s, a period marked by the detention and execution of scores of Shia Islamists and the expulsion of most of the foreign students from the seminaries. Those who were permitted to remain faced severe restrictions and constant surveillance by the regime’s security apparatus. In the aftermath of the failed Shia uprising of 1991, Jaafar’s father was detained when Iraqi troops retook Najaf. He disappeared, presumably buried in one of the mass graves where thousands of Shia were dumped.

It fell to Jaafar, who was seventeen at the time, to organise his family’s escape from Iraq. ‘We had no exit permits, and our Lebanese passports had expired,’ he said. ‘But I found a Jordanian smuggler who took me, my mother, four brothers and a sister across the desert into Jordan. From there, we made our way back to Lebanon through Syria.’

The Lebanon that Jaafar and his family returned to was drastically different from the one they had left two decades earlier. The civil war had scarred society, towns and cities were wrecked, and their village in the south was under Israeli occupation. Yet at the same time their status as Lebanese Shia had improved. In the mid-20th century the Shia constituted the largest and most impoverished community in Lebanon. Marginalised by the ruling elite in Beirut and oppressed by their semi-feudal local leaders, the peasants of South Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley in the east began migrating to the shanty towns on the edge of Beirut – the ‘misery belt’ – in the 1950s. Others went to Africa and Latin America. The rate of displacement increased with Israeli incursions into Lebanon and punitive campaigns targeting PLO bases. New waves of Shia migration to Beirut followed the outbreak of the civil war in 1975 and the Israeli invasions of the south in 1978 and 1982.

The difficulties faced by the residents of these shanty towns, mostly but not exclusively Shia, were exacerbated by the exploitative capitalist system established during Beirut’s belle époque. Many young Lebanese Shia gravitated towards communist and labour movements, as well as militant and leftist Palestinian factions. By the late 1960s, Musa al-Sadr, a charismatic Iranian-born cleric, had begun mobilising the Shia by tapping into their socioeconomic and political grievances. He founded a movement called Harakat al-Mahroumin (Movement of the Dispossessed). Rooted in Islam – though infused with rhetoric of social justice borrowed from the left – it sought to empower the Shia within Lebanon’s confessional system. Al-Sadr offered an Islamic alternative to the secularist ideologies that prevailed among educated and professional Shia, while effectively breaking the hold of the established Shia leadership of feudal lords and clerical families.

On the eve of the civil war, Amal was founded as the armed wing of the movement. After al-Sadr disappeared in 1978, Amal allied itself to Syria, sometimes fighting alongside the Palestinians, sometimes against them, according to the whims of its Syrian masters. By the end of the war, partly as a consequence of its close connections to Lebanon’s Syrian-dominated government, Amal had become a political party with an associated militia, which used its access to state resources to enrich its members through a corrupt patronage system.

As Amal started to decline in the late 1980s, Hizbullah gathered a significant following, particularly in Beirut’s southern suburbs. Its radical Islamist outlook, which had once led it to call for the creation of an Islamic state in Lebanon, had been tamed. It gave attention to social and economic issues and participated in national and local elections, while at the same time continuing its armed resistance against the Israeli occupation in the south.

Sect-based, family-based and village-based networks have historically provided essential services to the lower classes in the absence of state-sponsored programmes. Hizbullah, however, replicated an Iranian model, developing its own extensive infrastructure of social support separate from the traditional system. Through its civilian organisations, it implemented ambitious economic projects, transforming the party from one that drew its support primarily from displaced and radicalised lower-class Shia – the backbone of the muqawama (resistance) against Israel – into a broader movement attracting engineers, doctors and teachers from an emerging professional middle class. Jaafar and his brothers and sisters were part of that class. Their children went to schools run by Hizbullah’s education institute, they took microcredit from its loan fund, they visited and worked in the hospitals – some of the biggest in Lebanon – run by the Islamic Health Committee.

Despite its close alliance with Iran, Hizbullah had evolved into a distinctly Lebanese party in the years leading up to and following the liberation of South Lebanon in 2000. Its commitment to defending Lebanon’s sovereignty and national interests enabled it to appeal to the Lebanese and Arab population more broadly. While its rhetoric remained rooted in Islamic and Shia ideology, it also incorporated elements of Lebanese and even Arab nationalism.

These changes did not undermine Hizbullah’s militancy or its commitment to resistance, but strengthened them, by fostering a large popular base. The relationship between Hizbullah and its base in a way resembles that between the vanguard party and revolutionary communities in Marxist-Leninist literature. The resistance – almost exclusively Shia, though some have other sectarian and political affiliations – not only serves as a base of political support but also fosters a wider Shia and Lebanese identity, while reinforcing solidarity within the sect through mutual aid to advance the goals of the resistance. After Israel’s withdrawal, Hizbullah countered calls for it to disarm. It rejected the accusation that it was a state within a state, with a near monopoly on decisions about war and peace with Israel, by arguing that the Lebanese state had never been capable of defending the southern population from Israeli aggression, and that disarming it would amount to surrender.

‘Ifound your hard drive in the rubble,’ Hadi told his father. ‘I hope it’s still working.’ Jaafar was relieved: it held not only his PhD thesis but also family documents and photographs from their life in Tyre. Hadi also found a small leather purse which held a passport photo of Sara in a red headscarf, a black and white picture of her grandparents and her Lebanese passport. Jaafar flipped through its pages. Sara had travelled on it only once, last summer, when she visited Iran with her mother. From an inside pocket of the purse, he pulled out a small white card. It read: ‘I, Sara Jaafar, state that I refuse to recognise the state of Israel.’ Jaafar turned the card over a few times. ‘I never knew she was interested in politics,’ he said, smiling. ‘I mean, I know that, like all of us, she supports the resistance, but I thought they weren’t allowed to discuss politics at school.’ He always used the present tense when talking about his daughter or wife, as if refusing to acknowledge their deaths. He picked up the passport again and opened it at the first page, pointing to Sara’s date of birth. ‘She was born in the last days of the 2006 war. There was a huge bomb near us in Tyre, and Sayda had to be rushed to the hospital for an emergency birth,’ he said. ‘She was born at the end of one war and died in another.’

During Sara’s short lifetime, Hizbullah expanded its institutions and significantly increased its military strength. The civil wars in Syria and Iraq caused its militia to evolve from a highly disciplined commando force that operated in close-knit, religiously motivated units, into a semi-conventional infantry army. Hizbullah led and co-ordinated battalions of Iraqi, Syrian and Afghan fighters, with varying degrees of discipline, and deployed them across multiple borders. It sent advisers to battlefields as far away as Yemen. When the Lebanese economy collapsed, eventually leading to last year’s devaluation of the currency by 98 per cent, the party institutions shielded the community from the worst effects of the crisis. It provided healthcare and financial aid, issued discount cards for its supermarket co-operatives and expanded its interest-free microcredit system. It acted effectively as a state in the absence of a state.

The expansion came at a price. As the guerrilla movement, once built on secrecy, transformed itself into an infantry army fighting in several countries, it inevitably came into close contact with people outside its tightly controlled environment. This led to information haemorrhage, a fatal security risk. ‘The problem with Syria is that there were many formations fighting on the ground, and the role of the party was exposed,’ a senior analyst at a Hizbullah-affiliated research centre told me. ‘The Israelis could monitor its fighting and command structures.’ And as with most inflated bureaucracies, corruption and nepotism began to creep in, with lower-ranking party officials showing signs of accumulating wealth.

More than the string of victories won by the party and its allies, amplified by a highly effective multinational media operation, the sense of invincibility generated by the speeches of Hizbullah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, captivated the community. He had a remarkable ability to modulate his tone – speaking in classical Arabic in moments of fervour, only to fall back into a colloquial accent to mock his opponents. He was attuned to his audience: when they asked why men trained to fight Israel were supporting the corrupt regime of Bashar al-Assad, he calmly explained the importance of Syria to the resistance. He eased their fears again and again and assured them of victory. He promised that Israel, weaker than a spider’s web, would crumble, and that they would one day march into northern Galilee.

Hizbullah described the outcome of the 2006 war with Israel as a divine victory. It had denied the Israelis their stated goal of disarming the movement and inflicting heavy losses on its troops. But Hizbullah had to face the consequences of its own miscalculation: the war it had provoked on 12 July 2006 by crossing the border to ambush an Israeli army patrol ended with the massive destruction of Shia areas as well as severe damage to Lebanon’s infrastructure. The cost the war had exacted on the country, but especially on the Shia and the resistance community, forced Nasrallah and his fellow party leaders to pursue a strategy of deterrence while continuing to build up Hizbullah’s arsenal of weapons and underground fortifications. The deterrence policy worked for several years.

After the war in Gaza began, Hizbullah launched limited attacks on the Israeli border in what it described as a ‘support front’. For a while it thought it could maintain the rules of the old game, conducting limited skirmishes to the south. But late this year, a succession of Israeli attacks, starting with exploding pagers, the killing of several senior commanders, the killing of Nasrallah himself and then his successor, left many in the community asking: was supporting Gaza worth it?

‘The party had three options,’ the analyst said. ‘To enter the war fully, but that it couldn’t do because of the internal pressure; not to enter the war at all, and that it couldn’t do because it would weaken the party; or enter the war according to the existing paradigm. Hizbullah had no delusions, and it knew the Israelis and Netanyahu would go after the northern front. But what surprised it was the level of Israel’s technological advance and their capacity to infiltrate the party with electronic weapons. That was the big surprise.’

But the killing of Nasrallah and other leaders did not destroy Hizbullah. For two and a half months after his assassination the fighting went on, with Israel conducting strikes on South Lebanon, Hizbullah missiles still hitting Israeli cities and its fighters resisting the ground offensive. A ceasefire on 27 November, brokered by the US and France, brought a war that had severely damaged the party to an end. The wars in Gaza and Lebanon have had regional consequences. On 30 November, Syrian rebel forces took Aleppo and a week later Damascus fell, weakening the Iranian-built alliance and rendering worthless Hizbullah’s sacrifices of men and money. Whatever happens now in Syria, and whether or not the ceasefire in Lebanon holds, Hizbullah will return to its tactics of its guerrilla days of the 1980s and 1990s, in order to rebuild its cadres securely and carry on the fight.

At the funeral of those killed in Maaysrah, the coffins were draped in Lebanese flags. The prayers were led by an elderly local cleric. Standing beside him was another Shia cleric, Hizbullah’s representative in the region, along with a Sunni cleric and a Christian monk in brown habit, attending in a show of solidarity. After the prayers, the Hizbullah representative began his speech by berating the US and other Western powers for enabling Israel’s total disregard for international law, ignoring global opinion and setting an unacceptable precedent for future wars. He then turned his attention to the most pressing local question. ‘Here in the north we don’t have rockets and missiles,’ he said. ‘We are a very small minority, and all the intelligence services of the world have bases here. Here in the mountains of Lebanon, Lebanese law enforcement – that is, if there is anything like Lebanese law – can enter every house and every village if they want to seek out fighters. So I ask Israel: why are you bombing and killing children? The answer is to stir up conflict within society.’

Earlier that afternoon a missile had struck a house in the Christian village of Aitou, where several displaced Shia families from the south had sought refuge. The stone building was obliterated, killing 21 people. Within days, other Shia families who had rented houses in the village – presumed safe because of its Christian majority – were told to leave. Those who stayed, living on the outskirts of the village, faced daily inspections of their houses by neighbours, who suspected that they might be harbouring militants. For Jaafar and his family, there was no doubt that this was a war on the Shia.

Whether through the systematic demolition of Shia towns and villages in South Lebanon, with non-Shia ones spared, or the live on-camera destruction of residential blocks in Beirut’s southern suburbs, Israel’s war forced the displacement of more than a million Lebanese – almost exclusively Shia – from their homes. Many were uprooted multiple times. Late-night Israeli warnings sent entire neighbourhoods scrambling – on foot, in cars, on scooters – in search of shelter. Some lived in tents on the side of roads or on the seafront; others were packed into schools and public buildings, crammed into classrooms stacked with mattresses and cooking pots, courtyards strewn with laundry and overflowing bathrooms. Those who could afford to rent homes elsewhere faced discrimination and were forced to pay huge amounts. Everyone frets about the future; the war may have stopped for now, but there is nowhere left to return to.

The tragedy of this war is that it has all happened before. Punitive measures inflicted on the local population in the name of achieving peace and security has been Israel’s approach in South Lebanon since the late 1960s. It’s an approach that, over the decades, has served only to fuel more aggressive forms of resistance – legitimised in the eyes of much of the population by Israeli actions. Israel’s goal of ending the threat to its northern population is as elusive as ever. What set this war apart was its scale – enabled by sophisticated 21st-century American, British and European weaponry, extensive data-farming and AI-enhanced intelligence gathering – and Israel’s total disregard for international humanitarian law, with the targeting of medics, rescue teams and journalists.

Previous Israeli campaigns relied on the Dahiya doctrine, a strategy announced by the IDF after the 2006 war: the use of disproportionate force to cause extensive destruction. This war saw the use of what could be called the ‘Gaza doctrine’: the mass expulsion of a population. By razing villages and towns, declaring largely Shia cities like Tyre and Nabatieh no-go areas, and issuing expulsion orders to people living north of the Awali river, which marks the midpoint of South Lebanon, the Israeli war machine is not only attempting to create a security buffer zone, or to sever the ties between land, community and fighters (denying them their ‘water’ in the Maoist sense), but also leveraging a theoretical but unlikely ‘right of return’ for more than a quarter of Lebanon’s population as a bargaining chip in future negotiations to disarm Hizbullah. The war has deepened the fractures in Lebanon’s already fragmented society, turning the whole Shia population into potential targets. The analyst told me that with the killing of Nasrallah, opponents of the party in other sects will think that they now have an opportunity to uproot Hizbullah.

Men carried the coffins the short distance to the cemetery. A pack of photographers, foreign and local, jostled for pictures. Women followed behind, among them two girls of Sara’s age. In front of the cemetery were the ruins of another house, struck by missiles two weeks earlier, killing another sixteen people, relatives of the Hizbullah representative who had just given the speech. Jaafar’s brother-in-law, whose wife and four of his children had been killed, stood inspecting the graves with his surviving 12-year-old son.

‘When I arrived at the scene and began pulling out body parts, I said, “Ya Allah, now I understand Karbala,”’ the brother-in-law said. ‘Every year, on the day of Ashura, we commemorate the killing of Hussein and his children, the cutting off of their hands and legs. Now these body parts are our Karbala.’ The seventh-century Battle of Karbala has always been part of the collective consciousness. In times of success, it has been an inspiration, and in times of hardship it has assured believers that defeat can and will one day lead to victory. Israel is present in that consciousness more than ever, standing at the centre of every upheaval and mobilising a whole society. The 12-year-old boy stood beside his father. ‘I’m going to start my military training and avenge my mother and brothers,’ he said.

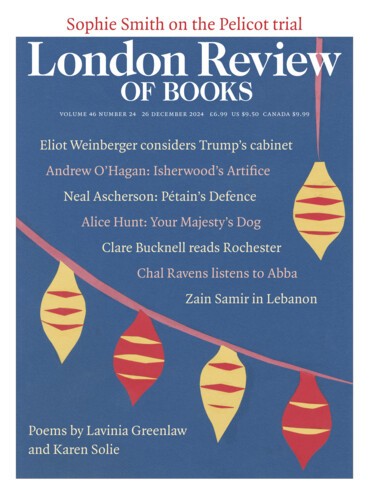

13 December

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.