At some point in the early sixth century, a well-born Irish monk arrived on Säckingen, a small island on the Rhine. Fridolin had already travelled through Gaul, discovered the relics of St Hilarius at Poitiers and reversed a bishop’s paralysis before Hilarius appeared to him in a dream and gave him another assignment: to find an uninhabited island among the Alemanni, the Germanic peoples of the Upper Rhine and the Danube, on which to build a church. Fridolin set off on his journey, founding abbeys as he went. But when he got to Säckingen the locals took him for a cattle rustler, whipped him and chased him away. Fridolin complained to Clovis, king of the Franks, and returned with a signed charter granting him the island, as well as two messengers who threatened any dissenters with immediate execution.

Fridolin established a nunnery, but he needed funding for the abbey. Things seemed to look up when Urso, a rich nobleman from Glarus (in what is now Switzerland), agreed to leave his property to Fridolin for the establishment of an abbey and died soon afterwards. But Urso’s brother Landolf ignored the will and seized the lands; Fridolin was told that he could only claim his inheritance if the testator confirmed it in person. He went to Urso’s grave, summoned him out and marched the corpse six miles to the court. After Urso publicly upbraided his brother, a cowed Landolf agreed to hand over his own wealth to the Abbey of Säckingen, and Fridolin returned the dead man to his grave.

So goes the legend. Most of it was written down in the tenth century by a Säckingen monk called Balther. The Urso episode was added in the 13th century along with other miracles. Some saints are identifiable by the instruments of their martyrdom – Catherine carries her wheel, Sebastian is pierced by arrows, Lucy displays her eyeballs on a plate – but Fridolin became associated with a man he brought back from the dead to solve a legal dispute. In a painted wood relief made in Swabia around 1500, Fridolin helps Urso’s emaciated corpse clamber out of his grave. Urso grits his teeth from the effort and is naked but for a blue beret, presumably for his appearance in court. An 18th-century carving of Fridolin has him holding up a skeletal Urso, who has remembered to bring his legal documents with him.

Both pieces are on display at World Heritage of the Middle Ages: 1300 Years of the Monastic Island of Reichenau (until 20 October), an exhibition curated by the Baden State Museum and held at both the State Archaeological Museum of Constance and on Reichenau Island in southern Germany. Fridolin was just one of a series of early medieval missionaries who travelled from afar to preach, educate and build around Lake Constance and along the Rhine. According to one popular myth, Reichenau Abbey was founded by a monk called Pirmin who arrived with his men in 724. Reichenau had fertile soil, good irrigation and abundant woodland and vineyards, but it was also infested by serpents. Pirmin drove out the serpents, and for three days the waters surrounding the island swarmed with them. He built a home for his monks, before leaving to found monasteries elsewhere.

In its first three centuries Reichenau Abbey was one of the leading educational centres in Europe. Its abbots produced fine manuscripts for their own use and on commission. They were involved in Carolingian imperial politics and cultivated a network of monasteries that reached into modern-day France, Italy, Austria and Belgium. The curators are keen to emphasise the abbey’s cultural significance and its connections across a continent as yet undivided by nation-states. It’s the individual stories that stand out, however, even if many are filtered through legend or embellished by the occasional useful forgery.

A monastery, much like a modern university, is an institution that transforms symbolic power into land, buildings and funds. In 896, the enterprising Abbot Hatto III, who moonlighted as archbishop of Mainz and chief chancellor of East Francia, returned from Rome bearing the skull of St George – a good excuse to build. Work began at once on the Church of St George, and in the tenth century it was decorated with a series of large secco wall paintings featuring miracles from the life of Christ. No other cycle of its kind survives north of the Alps. Hatto also wrote a life of St Verena of Zurzach, an Egyptian woman who accompanied the Theban legion to Europe in the third century and became famous in the Swiss canton of Aargau for the care she gave to girls and lepers. She is often portrayed washing the hair of the indigent or holding a jar and comb. A Verena reliquary on display in Constance is designed in the shape of an arm, its sleeve covered with precious stones arranged into flowers. Like other ‘speaking reliquaries’, the shape of the container hints at the type of bone it holds, but this one includes an extra detail: instead of showing an open palm, as is typical, the reliquary’s hand holds a brilliant golden comb, filigreed and embellished with even larger gemstones.

A section of the exhibition is dedicated to one of Reichenau’s most celebrated scholars, Walafrid Strabo (or ‘Squinty’). Born around 808, Walafrid was educated at the abbey and hadn’t yet turned eighteen when he wrote a poem based on a vision of the afterlife that appeared to his fellow monk Wetti. He wrote lives of local saints, studied biblical commentary at Fulda with the great Carolingian scholar Hrabanus Maurus and served Louis the Pious at Aachen. He also composed a poem on the art of gardening – the first such treatise in Europe – in which he describes the pleasures of eating a juicy melon (so easy on the molars) and recommends catmint and rose oil for treating scars and crushed lilies for venomous snakebites. This list of plants may have extended beyond those found in the monastery garden, but locals still call Reichenau the ‘Gemüseinsel’ (‘vegetable island’), and claim that its horticultural tradition dates back to the Middle Ages.

Walafrid’s most ambitious project, if the exhibition’s curators have attributed it correctly, was the Plan of St Gall (c.825), a red and black drawing that appears here only in reproduction and is thought to have been developed with Reginbert, the Reichenau librarian. This was an architectural plan for a monastic complex dedicated to Prior Gozbert of the Abbey of St Gall, though it’s not clear whether it was ever meant to be built in this form. It provides for every need of an early medieval Benedictine monastery: an infirmary and a garden for medicinal herbs; a bakery; stalls for goats, swine and geese; a school, library and scriptorium; a separate area for tending to the needs of the poor; and accommodation for guests of various ranks.

Reginbert was a distinguished figure in his own right. During his time as librarian he took stock of the abbey’s book holdings, many of which he had acquired or copied himself, and produced one of the first organised library catalogues of the Middle Ages. He encouraged Walafrid to write a history of Western liturgy (another first) and asked two other monks, Grimalt and Tatto, to make a copy of an authoritative version of the Rule of St Benedict while in Aachen. His own handwriting appears in the exhibition on the tattered flyleaf of a ninth-century collection of saints’ lives. The body of the manuscript is clean and neatly copied, but the first sheet is stained, wrinkled and marred by pen trials and small holes. Reginbert made a summary of the volume’s contents at the top of the page; in a colophon below he identified himself as its scribe and referred to the labour involved in making the book. ‘And, by God, I implore that it not be given or lent to anyone outside the monastery,’ he added, ‘unless he take an oath and offer a pledge for it, until he returns it whole and unharmed to its place.’

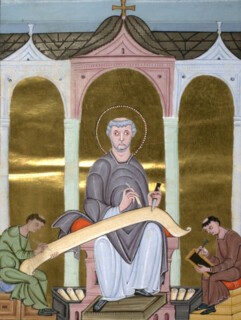

At the centre of the exhibition is the series of illuminated manuscripts made at Reichenau between 960 and 1030, during the Ottonian rule of the Holy Roman Empire. Its treasures include a Gospel book produced by two brothers, Burchard and Konrad, for Hillinus, a canon of Cologne. The dedication page shows Hillinus presenting the book to St Peter and, above the two men, an accurate image of the old Cologne Cathedral, which was built in the ninth century. (The illustration corresponds to the excavated remains of the foundation walls.) In Constance, the book is open to a full-page illumination of St Jerome at work on a scroll with the help of two scribes. They are seated in front of the arches of a church, backlit by shining gold leaf. Jerome is imperial in his flowing purple-grey robe, with a halo that resembles a string of pearls. The image is dominated by the yellowish scroll, which seems to be leaping out of the hands of one of the scribes and into Jerome’s lap, where he pins it down with a penknife. The scene hints at the stresses of working in a monastic scriptorium: the man to Jerome’s left, taking dictation on a wax tablet, casts a worried look; Jerome himself has a three-day beard and his eyes point in different directions, as though trying to watch both scribes at once.

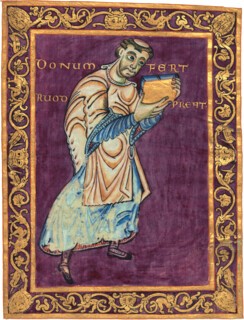

Ottonian illuminations often feature figures in richly detailed clothing posing formally against flat backgrounds and framed by bold, geometric designs. A psalter made for Archbishop Egbert of Trier in the late tenth century begins with a two-page dedication that shows the monk Ruodprecht humbly bringing the book to the archbishop. Ruodprecht’s head is bowed, his face has a green tinge and he seems to be gulping nervously, but he has dressed well for the occasion: the hem of his yellow tunic is embroidered and the sleeves of his blue frock hang in elegant pleats. Even his shoes are decorated, with rows of buttons. In the oldest surviving manuscript from Reichenau, the Gero Codex, an abbreviated gospel produced by the monk Anno shortly before 969, each evangelist has his own page. John sits serenely on a dais, one hand poised to dip his quill in ink while the other holds open a book. His toga is decorated with a gold circular pattern that recalls church windows and his orange halo is embellished with petals that echo the elongated arches behind him.

There is a simplifying impulse behind these images, an urge to distil historical and biblical events into colour. In a sacramentary, or liturgical book, made around 980 and now in St Paul im Lavanttal in southern Austria, a grey Christ is shown on an equally grey cross. His beard is choppy, his face gaunt, and he has dark circles under his eyes. But behind this colourless form is a background of knots and flowers in vivid shades of pink, peach and red. It’s as striking as anything you’ll see in illuminated manuscripts: a 1970s wallpaper pattern created more than a millennium ago on a little island in the Rhine.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.