The great auk, or garefowl, was a flightless North Atlantic seabird and it tasted delicious, perhaps a little like duck with a hint of seaweed. It’s hard to be sure because by the 1860s the great auk was extinct. It had once been abundant: in the 16th century, a breeding ground off Newfoundland – known as Funk Island for the overpowering stench of guano – offered a welcome source of sustenance for European sailors crossing the Atlantic. One sailor wrote that there was ‘more meat in one of these than in a goose’; another described the auks as ‘so fat that it is marvellous’. By the early 19th century, their breeding grounds had dwindled to a few isolated outposts, including two seastacks off the southern coast of Iceland. A volcanic eruption in 1830 caused one to sink beneath the waves, leaving just Eldey, a seven-acre lump of rock, as their last known stronghold.

In 1858, two English ornithologists went to see the great auk for themselves. John Wolley and Alfred Newton travelled to the south-west peninsula of Iceland, hoping to visit Eldey and return with some specimens to add to their collections. Newton even dreamed of capturing a live auk for London Zoo. But their trip was a failure. Bad weather made the journey to Eldey impossible; worse, they established that nobody had seen a great auk for years.

In The Last of Its Kind, the anthropologist Gísli Pálsson uses the great auk to consider the ways in which Victorian scientists thought about extinction, relying especially on Wolley and Newton’s unpublished notebooks. Wolley, the older of the two, was a gentleman collector. After a privileged and eccentric childhood – snakes in a drawer at Eton – he graduated in medicine but never practised as a doctor, choosing to spend his time collecting eggs. He travelled across northern Scandinavia in pursuit of rare birds, living among the Sámi and eating reindeer flesh (‘raw and as hard as a board’) while writing letters to his aunts in England. The locals called him ‘Äggherren’: Lord of the Eggs. His friend Newton had helped fund his excursions by arranging the sale of duplicate eggs and skins at an auction house in Covent Garden. The two men had long been intrigued by Iceland’s ornithological rarities, including the legendary great auk, and this time Newton joined Wolley on his mission. They set off from Edinburgh on a Danish steamer in April 1858. As the ship passed through rough seas around the Icelandic coast, they watched Eldey pass by on the horizon, not knowing that would be as close as they would ever get.

They had been looking forward to a ‘genuinely awkward’ expedition. But at their first dinner in Reykjavík, then a village of 1500 people, they were dismayed to be served eider and red-breasted merganser. The weather was terrible, trapping them there for three weeks ‘in a chronic state of intoxication’ thanks to Icelandic hospitality. When they finally set off for Kirkjuvogur, from where they hoped to row out to Eldey, they took a veterinarian and a doctor who had business to attend to in the surrounding district. The vet’s horse fell on top of him; the doctor insisted on taking them on a detour to see a case of leprosy. When they arrived in the ‘miserable fishing village’ of Kirkjuvogur, they waited and waited for the weather to break. It didn’t.

Soon after their return to England, Wolley contracted a fatal brain malady and died aged 36. He left behind a collection of ten thousand eggs, which he bequeathed to Newton. In tribute to his friend, Newton decided to catalogue them. This was no small undertaking: the collection filled a railway carriage and weighed about a ton. The four volumes of the ‘delicately illustrated’ Ootheca Wolleyana took Newton forty years to complete.

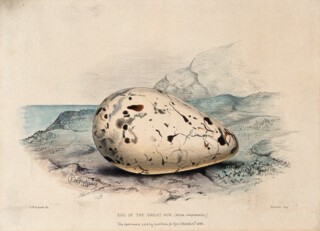

Oology – the study of eggs – has the nicest name of all the sciences. But collecting an egg is no different from stealing it. An egg in an oologist’s collection may appear intact, but it will have been pierced (sometimes twice) in order to extract its contents. The pristine shell once held the promise of new life; now it holds nothing at all. Great auk eggs were particularly sought after because of their size and beauty: a cream shell spattered with inky streaks and blotches. News of the bird’s extinction not only enhanced the rarity of the remaining eggs but lent them an almost mystical aura. They were no longer curios but holy relics. In his magisterial study of 1885, The Great Auk, or Garefowl, the ornithologist Symington Grieve provided a detailed appendix of the 68 eggs he had been able to track down, distributed across collections from Scarborough to St Petersburg.

As well as eggs there were also stuffed auks – though not all were genuine. An unscrupulous taxidermist could easily stitch together an ersatz auk from a patchwork of guillemots. It’s not uncommon for a museum today to discover that their prized specimen is a fake. Pálsson finds one in the Natural History Museum of Denmark. Another can be found in the local museum of my home town, Shrewsbury, from the studio of the outwardly respectable taxidermist Henry Shaw (alas, no relation). Genuine great auk skins would have been stuffed and made lifelike by taxidermists who had never seen one in the wild, often rendering questionable choices canonical. In 1912, the editorial board of the American Ornithological Society’s journal, the Auk, felt that one of the great auks frolicking in the background of their new cover artwork had its wings in an inappropriate position. By this point, the bird had been extinct for around sixty years. The artist sent back an amended cover with a poem: ‘A wise committee in New York/Have passed their word that this ’ere Auk/Conforms in feature and proportion/To the Museum’s stuffed abortion.’

Wolley and Newton had the benefit of speaking to people who had actually seen great auks. Drawing on work by the anthropologist Petra Tjitske Kalshoven, Pálsson picks out the moments from their interviews where locals impersonated the great auk: one man turned his head from side to side before ‘running across the room with tiny steps’. Wolley and Newton learned that two auks had been caught and killed on a hunting expedition to Eldey in 1844, with no reliable sightings since. The events are contested. Of the fourteen crew members, only three had landed on Eldey, grabbing one bird on the lowlands and one on the edge of a cliff before discovering a cracked egg. Some later accounts claim that a 21-year-old farmhand called Ketill Ketilsson had smashed the egg, but Pálsson finds that Wolley’s notebooks tell no such story. Ketilsson has been described as the man who personally wiped out the great auk, but he didn’t even catch either of the birds: ‘his head failed him in the chase.’ Yet the stories endure. In 2020 Ketilsson’s great-grandson wrote an article for an Icelandic newspaper defending his forebear.

Newton returned from Iceland without a great auk egg but with a new awareness of extinction. Pálsson argues that Newton understood humans to be a primary cause of species loss at a time when the idea was almost unthinkable. Even as industries such as whaling faltered, whalers attributed the decline in whales not to a fall in numbers but to increasingly evasive behaviour; they were supremely confident that more whales existed somewhere over the horizon to replenish the stocks. In Moby-Dick, Ishmael considers the possible ‘gradual extinction’ of the sperm whale but argues that the whales can always retreat to safety in their ‘citadels’ in the icy polar seas, ‘as upon the invasion of their valleys, the frosty Swiss have retreated to their mountains.’ Humans have been slow to accept that species are not eternal.

As the great auk’s extinction became indisputable, it attracted a particular kind of Victorian sentimentality. In Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies (1863), the chimney-sweep Tom meets the last great auk, a ‘very grand old lady’ sitting on ‘Allalonestone’ who tells the story of their extinction before weeping tears of pure oil. It’s revealing – if not surprising – that the grief is attributed to a maiden aunt. If male scientists felt grief at the idea of extinction, they were careful not to show it. In his afterword, Pálsson points out that Newton has nothing to say about the feelings of loss a great auk might have experienced after its egg was stolen.

Although Newton’s career was defined by the great auk, he saw himself as more than just an oologist. Others disagreed. When the Cambridge professorship in zoology and comparative anatomy became available in 1865, Newton wrote to Darwin asking for a testimonial. Darwin politely declined (‘If I am not mistaken, you have not published on these subjects, & have chiefly attended to Birds’). Newton was elected even so and spent the rest of his life living up to Darwin’s low expectations, avoiding teaching as much as possible in favour of cataloguing Wolley’s eggs. Where he does deserve credit is for his efforts to protect wild birds. The Sea Birds Preservation Act of 1869, drafted by a committee including Newton, made it illegal to hunt sea birds between April and August. But this applied only to the killing and taking of birds; Newton made space for the efforts of oologists. His muscular view of conservation saw no issue with killing birds in moderation (though he would be horrified by a recent RSPB report suggesting that four in ten British birds are now vulnerable to extinction).

Taking eggs from a wild bird’s nest has been illegal since 1954, but that hasn’t stopped the most ardent collectors. When the police raided the home of Daniel Lingham in 2004, he burst into tears. ‘Thank God you’ve come,’ he told them. ‘I can’t stop.’ Lingham has since been to jail twice and was convicted again earlier this year after he was captured on a wildlife trap camera as he raided a nest. When police searched his home they found three thousand eggs. The defence argued that his addiction to taking eggs was a mental health issue, and it’s hard to disagree.

Pálsson doesn’t delve too deeply into what Bruce Chatwin called ‘the psychology – or psychopathology – of the compulsive collector’. But his thoughtful and melancholy account gains complex resonance when he confesses his own childhood passion for birds’ eggs: he experienced ‘pangs of grief’ for his lost egg collection while writing the book. He visits the British collector Errol Fuller, whose house resembles a Victorian cabinet of curiosities, complete with hardwood cupboards that once housed some of Wolley’s eggs. Fuller himself owns two great auk eggs; he once had a share in a stuffed great auk but his co-owner sold it to a Qatari politician without asking him.

Reading Pálsson’s book, I felt the same dusty obsession creeping up on me: I wanted to see a great auk egg. From Symington Grieve’s appendix I knew that the Oxford Museum of Natural History had an example (no. 48 in his list). It’s no longer on display, but the curator, Rob Douglas, agreed to let me have a look.

I wasn’t allowed to hold it, but I watched with anticipation as Rob removed the dark-blue velvet cover with its label: ‘HANDLE WITH EXTREME CARE – egg of extinct bird!’ The egg was smaller than I imagined. It had the characteristic shape, however: sharply pointed at one end to stop it rolling off into the sea. I hadn’t expected to be able to see where the living material had been extracted, but the jagged ruptures at each end were clearly visible. I tried to imagine it whole, perched on a rocky ledge spattered with sea salt, surrounded by its full-grown relations.

Wolley and Newton both acquired great auk eggs after their failed trip. Newton eventually owned seven. One doesn’t have to be a psychoanalyst to see that the act of collecting is poised between the joy of ownership and the despair of loss. When Newton was moving Wolley’s egg collection to Cambridge, he confessed to doing so ‘amid an abomination of desolation’. He wrote to a friend: ‘I only wonder I am not driven quite mad and do not dream I am a Gare-Fowl’s egg about to be involved in a winding sheet of cotton wool and stored away forever.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.