In April 1966, Senegal hosted the Festival mondial des arts nègres (Fesman), the first global, state-sponsored festival of African art, music, drama, poetry, literature, film and dance in the era of African independence. It was the brainchild of Léopold Senghor, Senegal’s president, who saw the arts as a field of struggle. Two subsequent festivals took place, in Algiers in 1969 and Lagos in 1977, and their history bears out Senghor’s claim in a way he did not intend: they have faded into obscurity.

While studying and teaching in Paris in the 1930s, Senghor and a group of Caribbean intellectuals and writers, most prominently Léon Damas and Aimé Césaire, had spearheaded the literary movement known as négritude, an assertion of black identity and civilisation and a proclamation, at least on Senghor’s part, that black people possessed an essence and genius different from, and even superior to, that of Europeans or white people. This view was mocked by some African artists, intellectuals and political rivals. ‘A tiger doesn’t proclaim his tigritude,’ Wole Soyinka said. ‘He pounces.’ But négritude was the animating spirit of Fesman, which was a huge success.

Senghor took power in 1960 on Senegal’s independence from France. Shortly afterwards, he accused Mamadou Dia, his prime minister and long-time ally, of planning a coup. Dia was dismissed and jailed for twelve years. A year later, in 1963, Senghor announced a new constitution abolishing parliamentary democracy. Union members, students and opposition activists were imprisoned. At the same time, Senegal was facing economic crisis as the rapid growth and state-led industrial transformation that followed independence slowed. Peasants and farmers demanded higher prices for their peanut harvests (the country’s economic base) and ever larger subsidies. Senegal’s foreign policy continued to follow France’s lead: Senghor had always wanted the two countries to have a federal relationship. Senegal sided with the French against the FLN in Algeria and opposed its bid for independence at the United Nations. And Senghor appointed French, not African, advisers to his new government. ‘We asked for the Africanisation of the top jobs,’ Frantz Fanon said, ‘and all Senghor does is Africanise the Europeans.’

The government built a new national theatre and a national museum for the 1966 festival. The list of participants is impressive, especially the American delegation: the dancers and choreographers Arthur Mitchell, Alvin Ailey and Katherine Dunham; the musicians Duke Ellington and Marion Williams; the writers Langston Hughes and Amiri Baraka. Senghor’s friend Césaire made an appearance, as did the Barbadian writer George Lamming, the South African writer Keorapetse Kgositsile and singers and dance troupes from Brazil and Trinidad and Tobago. Despite his scepticism about négritude, Soyinka came to see the premiere of his play Kongi’s Harvest. The historian Cheikh Anta Diop, who controversially argued that Egypt was a black civilisation, was one of the host country’s representatives. A symposium extolled the virtues of négritude.

The celebratory tone masked tensions over the festival’s vision of Africa’s present and future, and over the choice of participants. At the start of the year, representatives from a group of newly independent states and national liberation movements from Africa, Asia and Latin America had met in Havana. The Tricontinental Conference hosted by Fidel Castro backed the liberation of the remaining colonies by methods including armed struggle. Senegal didn’t send a delegation. The conference took a stronger position than the Bandung Conference of 1955 or the Non-Aligned Movement, with which Senghor identified. The closing speaker in Havana was Amílcar Cabral, who led Guinea-Bissau’s revolt against Portuguese colonialism. He was a close ally of Kwame Nkrumah, the president of Ghana. A few weeks after the conference in Havana, Nkrumah was overthrown in a military coup. He had become an unpopular and authoritarian ruler, but there were rumours that the CIA had a hand in his downfall, unhappy about his leanings towards the Soviet Union and China. Senghor remained silent as Nkrumah, who had been on a state visit to China when the coup took place, fled to Guinea, another former French colony. Sékou Touré, the Guinean president and an outspoken critic of France and négritude, was Senghor’s main political rival in francophone Africa.

The most significant controversy at Fesman, however, was over the invite list. The organising committee only asked national delegations, so representatives of the liberation movements still fighting in Southern Africa and the Portuguese colonies weren’t invited. Some artists, such as Kgositsile, a member of South Africa’s banned and exiled ANC, turned up anyway. Senghor decreed that Arabs from North Africa couldn’t be exponents of ‘Negro arts’, on the basis that they were representatives of an ‘Arab-Berber’ cultural ‘zone’ and therefore not part of ‘Negro-African’ civilisation. At first, he wouldn’t budge on this supposed principle, but later, under pressure, he allowed North Africans to attend as observers. He allowed the US State Department to pick the American participants – theirs was the second largest delegation after Senegal’s – and to appoint a white woman, Virginia Innes-Brown, as their de facto leader. Most of those chosen, including Ellington, Dunham and Louis Armstrong, had taken part in earlier ‘cultural diplomacy’ tours, which aimed to counter the growth of left-wing politics among former imperial subjects. Younger and more radical artists weren’t selected. Baraka, who brought a new play about slavery, was an exception.

Many of the delegates felt the proceedings were staid and formal, distrusted Senghor’s obsession with impressing Europeans and were unhappy that ordinary Senegalese were excluded. But Senghor didn’t have everything his way. One of his most prominent local critics, Ousmane Sembène, a former dockworker who had studied film in the Soviet Union, won the festival’s film prize for La Noire de . . . Its main character is a Senegalese immigrant in France who commits suicide after being badly treated by her employers.

Senghor wanted Nigeria to host the next festival. But after two military coups in 1966, one before and one after Fesman, Nigeria descended into civil war. With the backing of the Organisation of African Unity, some of Senghor’s critics convinced Algeria to host a Pan-African Festival, or PANAF, in 1969. The Algerian government saw itself as a leader of a resurgent Third World, and Algiers had become home to many African and African-American radicals. It also served to counter North Africans’ marginality at Fesman.

The Pan-African Festival ran from 21 July until 1 August 1969. In many ways, it was very different from its predecessor. As well as the equal participation of North Africans, its goal was to link pan-African culture with ‘an ongoing global process of political liberation from Western rule’, as David Murphy puts it. To drive this point home, representatives of Swapo from what is now Namibia, the African People’s Union from Zimbabwe and the ANC and Pan-Africanist Congress from South Africa were invited, and marched in the opening ceremony, a street parade through Algiers. The Black Panthers were asked too – Eldridge Cleaver had just taken refuge there – as was the PLO.

Some of the same artists appeared at both festivals, but Algiers felt more like a carnival, with many events held outside in public squares where ordinary Algerians and visitors could watch. The headliners included the R&B singer Barry White and radical artists such as Archie Shepp, Nina Simone and Miriam Makeba. In William Klein’s Festival panafricain d’Alger 1969, Shepp can be seen on stage with some Touareg musicians. Ted Joans, introducing him, shouts, ‘Jazz is a Black Power!’ ‘We are all Africans,’ Makeba declares to applause. ‘Some are scattered around the world living in different environments, but we all remain black inside.’ The historian Andrew Apter identified the fundamental difference between the politics of Dakar in 1966 and Algiers in 1969: ‘Black culture in Algiers was forward-looking and revolutionary, unified and motivated by the shared struggle against Euro-American racism and imperialism – bringing French colonialism and American segregation (with its associated prison-industrial complex) within the same oppositional battlefield.’

At the festival symposium, delegates, especially those from West and Central Africa, focused on denouncing négritude and Senghor as counter-revolutionary. In a forty-minute pre-recorded message, Touré argued that ‘there is no black culture, white culture, yellow culture … négritude is thus a false concept, an irrational weapon encouraging the irrationality based on racial discrimination, arbitrarily exercised upon the peoples of Africa, Asia, and upon men of colour in America and Europe.’ Unlike Senegal, Guinea had refused to join a French monetary union or to maintain close relations with it – or its corporations – after independence. France retaliated by, among other things, opposing Guinea's membership of the UN, sabotaging its economy and fomenting a (failed) coup against Touré's government.

The Biafran War ended in January 1970; around two million people died as a result of the conflict. General Yakubu Gowon, the Nigerian head of state, announced that the Second World Festival of Black Art, or Festac, the new name reflecting changes in racial terminology, was back on the cards. A committee, which included Senghor and had the Senegalese writer Alioune Diop as secretary-general, decided on November 1974 as the festival date. Gowon made Senghor and himself its co-patrons. But the 1974 deadline came and went. In July 1975, Brigadier Murtala Muhammad overthrew Gowon. He too committed Nigeria to hosting the festival, but seven months later, he was assassinated in another attempted coup and his chief of staff, Olusegun Obasanjo, took power.

Obasanjo’s tenure coincided with huge economic growth in Nigeria: between 1960 and 1973 oil output increased from five million to more than six hundred million barrels. By 1971, when it joined OPEC, Nigeria was the world’s seventh largest oil producer. It was suddenly a very wealthy country, and one consequence of this was that the military fast-tracked festival preparations, giving a new date of 1977. Registered participants would be issued with identity cards and live in the specially built Festac Village (which cost $80 million). The festival was ahead of its time in terms of branding: Festac had its own flag (black and gold), stamps, song (by King Sunny Ade), toilet paper, T-shirts and cups. Marilyn Nance, an official photographer for the North American zone, described the branding as ‘the Olympics, plus a biennial, plus Woodstock. But Africa style.’ The festival’s emblem was the 16th-century ivory mask of Queen Idia of Benin, exemplifying the desire to use Africa’s precolonial heritage to help build a new global black consciousness, with Nigeria at its head. The mask was among thousands of artefacts looted by British soldiers during their conquest of Nigeria in 1897. The Festac ’77 organisers asked the British Museum to lend the mask for the festival, but the museum demanded an indemnity of $3 million. In a precursor to current efforts to repatriate African art, the Nigerians tried to get Unesco involved, but without success. Instead, they commissioned a local artist, Felix Idubor, to carve a replica.

In the run-up to Festac, Senghor – affronted by what had happened in Algiers – revived the debate about ‘Arab-Berber’ and ‘Negro-African’ essences. But the Nigerian military decided it would be discriminatory to exclude Arab and North African artists and performers, and would undermine continental solidarity. The Senegalese threatened a boycott. In response, the generals fired Diop as festival director, removed Senghor as co-patron and changed the festival’s name to the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture. Following Algiers’s lead in 1969, the organisers invited representatives of liberation movements. They also invited black people from Australia and the South Pacific.

At least fifteen thousand delegates from more than fifty countries arrived in Lagos. The largest national delegation was from the US, with 482 people. The Nigerians had no intention of working with the State Department to pick the delegation, instead asking a black-run NGO based at Howard University to help. The participants included the feminist writer and activist Audre Lorde; Sun Ra, Stevie Wonder and Randy Weston; the then US ambassador to the UN, Andrew Young; the artist Barkley Hendricks; the veteran activist Queen Mother Moore; and the black Muslim leader Louis Farrakhan. But most of the Americans who attended were relatively unknown. Among them was Marilyn Nance, who was 23.

Nance, who was born and grew up in public housing on the edge of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, had been thirteen at the time of the Dakar festival. Her great-grandparents had been enslaved in the American South, and her grandmother, born in 1886, ‘knew that she was an African woman’. Aged eight, Nance was given a camera by a cousin and she went on to study photography at the Pratt Institute, near where she grew up. As part of her application to Festac she submitted a photograph of her grandmother sitting in her kitchen in Alabama. She was accepted, but then dropped from the final list in 1976. She badgered the North American organisers and was eventually allowed to make the trip as a photo technician. When she got to Lagos she was promoted to official photographer of the North American zone. Nance travelled light, bringing only two small cameras: a Canonet point-and-shoot and a Miranda Sensormat (her first camera). She also took her own film.

Most of the American participants went home after two weeks, but Nance stayed for the rest of the festival and took an astonishing number of pictures – more than fifteen hundred images, most of them black and white, showing cheering spectators, the police and military guarding them, the national delegations marching at the opening ceremony, performers waiting their turn and musicians rehearsing and performing. She also captured encounters between the artists and activists, especially her fellow Americans. ‘I didn’t even know [Audre] Lorde was there until I was reading part of her biography … and then realised I had taken two pictures where she appears,’ she later said.

‘I went to Nigeria thinking, I’m an African person. I’m removed from the continent, but here I am, returning,’ Nance said. ‘But, when I arrived, I realised we weren’t seen as African people. We were seen as Americans. That was the first time I ever really felt myself as an American.’ But she didn’t fully feel American. This may be the reason Festac’s projection of itself as representative of a ‘pan-African nation’ was so attractive to her. She didn’t feel separate from the people she photographed:

I was part of the whole thing. I don’t call it capturing an image. I don’t call the people in front of me my subjects. I don’t shoot, I make images. I’m so much a part of the images that I make that I become invisible, which is quite a good thing and quite a bad thing, depending on how you look at it.

Nance avoided political controversy, making only one image that had a connection with oil: it shows young men leaning over an Esso petrol pump. Years later, she remembered Festac mainly as ‘a great party’. She ‘wasn’t thinking about oil’. Numerous contemporary reports of the opening ceremony relate the brutal actions of the police. A report in Ebony magazine, aimed at black American readers, said that ‘several people died’ when police and military clashed with the crowd: nearly 100,000 people turned up at a stadium with a capacity of 60,000. Though the American visitors saw soldiers with machine guns everywhere (they appear in a few of Nance’s photos) and knew that Nigeria was a dictatorship, Nance did not seek out these subjects.

She did remember seeing Fela Kuti, who was then at the height of his fame. Kuti was an outspoken opponent of the Nigerian military and had been involved in the planning of the festival before falling out with the organisers over spending (costs had ballooned to more than $400 million), corruption and the disproportionate presence of the military on the organising committees. After resigning, he held a press conference, calling the festival ‘a huge joke’ and encouraged visitors and locals to attend performances at his Afrika Shrine instead. Nance went. Stevie Wonder, Sun Ra, the Ghanaian-British superband Osibisa, the Brazilians Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, and the South Africans Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba all went to listen to Kuti perform revolutionary songs or to join him on stage.

Less than a week after Festac ended, Obasanjo ordered a raid on the Afrika Shrine. Kuti’s criticism of the festival wasn’t his only offence. He had declared his compound a republic (‘Kalakuta’) and announced that he would run for president. Most dangerous of all, he was attracting the attention of the city’s restive young population. A thousand soldiers stormed Kalakuta, stole the money from his latest record deal, beat up his followers, sexually assaulted some of the women in his band and threw his elderly mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, a well-known anti-colonial campaigner, from a second-floor balcony. She died a year later, as a result of her injuries.

The next Festac was supposed to be organised by Ethiopia, then ruled by the Derg, a junta whose members showed little interest in the arts. The famine that killed a million people between 1983 and 1985 put an end to such plans. Festac had tried to inculcate a belief in African self-reliance, but the Ethiopian famine ushered in an era of celebrity-driven humanitarianism on the continent and the association of Africa with ‘crisis’.

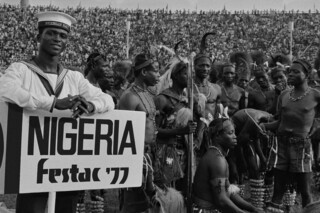

After Nance returned to New York, she suggested the idea of a photobook about Festac to several publishers, but there was little interest. She decided to make a postcard of one of her images, which shows a member of the Nigerian navy at the opening ceremony next to a delegation in traditional dress, and sold it at black cultural festivals in and around New York City. Then she found a job in advertising, married and began making films with her husband, Al Santana, about African-inflected religious ceremonies and traditions in the United States. The memory of Festac ’77 faded. No one wanted, or had the money for, a global arts festival showcasing African culture.

In 2009, Algeria celebrated the 40th anniversary of PANAF, but it didn’t receive much attention. That same year, at a press conference at the UN, Abdoulaye Wade, Senegal’s president, announced plans for a Third Festival of Black and African Art in Dakar in 2010. Wade’s principal collaborator was the Senegalese-American R&B singer Akon. Both men needed a lift. Wade had been voted into office in 2000 on the back of a popular revolt by youth activists against his predecessor, Abdou Diouf, who had served as Senghor’s prime minister. These same protesters were now complaining about Senegal’s economic problems and Wade’s bare-faced attempt to change the constitution to prolong his own rule beyond the mandated two terms. Akon had built a career singing saccharine pop ballads and rap hooks. Now he wanted to rebrand himself as an entrepreneur. He announced schemes for the mass electrification of African cities and the construction of smart cities on the continent. Wade’s festival did take place, and more than six thousand artists from more than fifty countries turned up, but most Senegalese boycotted it.

But this wasn’t surprising. Young Africans had grown sceptical of state initiatives. They saw their governments as impotent in the face of structural adjustment, neoliberalism, the effects of globalisation and great power struggles over African resources. In 2012, Wade was voted out. The name of the collective of rappers and activists that galvanised the opposition translates as ‘Fed Up’. ‘“Negro-African” culture grows deeper through the people’s struggle,’ Fanon wrote, ‘and not through songs, poems or folklore.’

In 2014, Nance had her contact sheets from the festival digitised. She started giving talks about her experience at Festac, and in 2016 was asked to talk about her images at a conference on ‘Black Portraiture’ in Johannesburg. Remi Onabanjo, a young Nigerian-American she met there, convinced her to compile a book. Last Day in Lagos includes a long interview with Nance by Onabanjo and a series of essays by North American critics, as well as about a hundred of her images. The essays mainly concern questions of belonging, African and black identity, and black consciousness. Reading the interview and the essays or leafing through Nance’s photographs, you realise that Lagos is really a backdrop for black American debates about Africa. Nance doesn’t ask the same questions or make the same demands about rights, democracy and accountability of Nigeria that she would of the US. She admits that her images reflect ‘romantic notions of pan-African unity, my nostalgia for this incredible celebration of world culture’.

Nance told Onabanjo that when she returned from Lagos in 1977, she wanted to do ‘a Festac scrapbook kind of thing’. In 2019, Chimurenga, a Cape Town publisher, produced Festac ’77: Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture. It looks like a book of newspaper cuttings – the editors describe it as ‘decomposed, un-arranged and reproduced’ – and is accompanied by a mixtape curated by Ntone Edjabe, the founder and editor of Chimurenga. It is less celebratory than Nance’s book, less self-conscious about identity and race, and more straightforward about the graft and influence-peddling that was a legacy of colonialism and has become part of Nigerian politics.

Chimurenga, which was founded in 2002, means ‘revolutionary struggle’ in Shona, and the term is used to describe the struggles in the late 19th and mid-20th centuries for Zimbabwean independence. Festac ’77 took inspiration from Toni Morrison’s Black Book, published in 1974, which used a scrapbook style to tell the cultural history of African Americans in the United States. Morrison described the result in 2003 in an interview with the New Yorker. The Black Book was a ‘genuine Black history book – one that simply recollected Black life as lived. It has no “order”, no chapters, no major themes. But it does have coherence and sinew.’

Festac ’77 begins with a photocopy of a 1977 survey by the Department of Mass Communication at the University of Lagos that was handed to festival participants. Respondents were to answer 92 questions, including ‘What is a good life?’ This is followed by reprints of speeches (some in Arabic, French and Portuguese), essays, art, posters, press clippings, journal entries by festival participants, magazine covers, minutes of meetings, architectural plans, post-festival assessments, photographs (most of them uncredited) and photocopies of pamphlets. They combine to tell the festival’s story in a chaotic and sometimes incoherent but more complete way. The effect is to capture the headiness of that time for Nigeria and the black world. The material also makes clear the festival’s ideological diversity. According to Andrew Apter in his 2021 article ‘Festac ’77: A Black World’s Fair’, Festac’s idea and vision of black culture and civilisation was ‘less concerned with policing boundaries and more about expanding them’. As a result, ‘communists from Cuba, capitalists from Côte d’Ivoire, and Marxists from Mozambique could promote competing political economies of culture within a welcoming celebration of common heritage.’

A number of key participants wrote essays on the festival’s legacy. Two, both reprinted in the Chimurenga book, stand out: Soyinka’s 2008 ‘Festival Agonistes’ and the Ghanaian writer Ayi Kwei Armah’s ‘The Festival Syndrome’, first published in 1985. Both pieces reflect on the debates that predated the festival and consider the significance of the needless bureaucracy and corruption that surrounded it. ‘What I encountered in Lagos was truly dispiriting,’ Soyinka writes of his return from exile in Britain in 1975.

There was a frank and unapologetic effort, led from the very top, to drag the preparations out as long as possible, in order to milk this cash cow of its last drop. Festival spirit there was none, only the chop-chop spirit – ‘eat your own and I eat mine’ – that began from the very top leadership of the organisation, percolated through the entire bureaucratic set-up and, to my intense distress, even infected the artists.

A rich friend of Soyinka’s met with Festac’s representative in London. His host said he was happy to meet him ‘because you sounded interesting and you’re from my own state’. Otherwise, he said, he’d be playing golf. He told him how to get his cut from any donations he decided to make.

‘Festivals of the Festac and Dakar kind are,’ Armah wrote, ‘as far as any intelligent contribution to cultural flowering in Africa is concerned, the opposite of medupe [gentle] rain. They are infrequent, loud, spectacular affairs, and in their effects they are useless, if not downright harmful.’ He criticised the money wasted on plane tickets, food allowances, accommodation, expense accounts, and bureaucrats’ salaries:

These festivals do little to improve the condition of African culture, to create viable institutions incarnating it, or to encourage those who create and recreate it … In Africa’s present situation, the best use of available resources and brainpower would be for creating the still missing supportive cultural network, not for holding more greasy, bureaucratic zombie jamborees.

The most visible legacy of Festac has proved to be Festac Town (no longer just a village). There were five thousand housing units, a police station and a fire station, health centres, recreational facilities, banks and post offices. The roads were well laid out, with seven main boulevards. After the festival ended, Festac Town became a desirable public housing estate. Since then, local, regional and state government have argued over who is responsible for its upkeep. As a result, it has become rundown; its infrastructure, including the sewage system, is in poor condition; roads are flooded or impassable; illegal structures are increasing; and housing units are overcrowded.

There is one group in Nigeria that is keen to remember the festival. Pentecostal Christians blame it for the country’s dismal state. They believe it celebrated ‘animistic heritage,’ ‘evil spirits’ and ‘idols’ – like the mask of Queen Idia. In April 2013, when Boko Haram’s violence was at its worst, Chris Okafor, ‘general overseer’ of the Liberation City Ministry, told congregants that he held Obasanjo responsible for dooming Nigeria. Another pastor, Margaret Osundolire, has since 2005 held an annual prayer service at the National Theatre – the same theatre that was built for the festival – to exorcise the demons unleashed by Festac. Every year, she invites Gowon and Obasanjo to attend and repent. Neither has yet accepted.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.