The virtue of Philip Guston at Tate Modern is to leave his outsiderishness intact – his oddity will not go away – while suggesting that Guston might be the mid-century American painter who matters most now. Or who can still offend. Philip Guston Now was the original title of the show, which was scheduled for 2021 but postponed by the participating museums, here and in the US, ‘until a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the centre of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted’. The pre-opening jitters, at a moment of national reckoning, concerned Guston’s cartoony (for want of a word) paintings of hooded Klansmen riding around town in toy-like cars, loaded up with evidence of wrongdoing, looking for trouble. Or, perhaps more troubling, views of hoods doing nothing much, sitting in nondescript rooms, head in hands, smoking, sunk in a permanent Sunday of urban anomie, a bit like us. Hoods having moods, hoods displaying the unlikely evidence of an inner life: ‘dumb, melancholy, guilty, fearful, remorseful, reassuring one another’, in the words of a Guston studio note.

The curatorial hand-wringing – over a handful of works painted fifty years ago, within the context of a large retrospective – said more about the institutions than about the pictures. The Boston version of the reinstated show opened last summer with leaflets on emotional preparedness (‘name your feelings’) written by an onsite trauma specialist, plus an emergency exit ramp ahead of the most offending room, and video montages of life-and-times historical footage, replete with horrors, to which Guston’s imagery must appear accountable. At the Tate, ‘Now’ has been dropped from the title, and wall-texts offer mild if constant reassurance as to Guston’s allegiances and good intentions. The allegiances were clear, and actively so in his early career, the intentions less so. A studio note from 1972 reads: ‘If someone bursts out laughing in front of my painting, that is exactly what I want and expect.’ The real shock of the Now is perhaps a new sense that paintings and the public can no longer be left alone in a room together – in case of laughter, which in this case is in the dark about itself.

Guston died in 1980, after a decade of figurative bad behaviour, following a notorious exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery in New York in 1970 – stuffed with Klansmen paintings, crudely drafted and wonderfully painted – in which he announced his apostasy from abstraction and walked off into the art wilderness. Among fellow practitioners, in the decades of post-abstraction and new realism that followed, the posthumous example of Guston gained ground, not least as ‘a paint-painter’ (his phrase for Honoré Daumier), under cover of his wider obscurity, which the scandal around the retrospective has certainly helped to clear.

The Tate show is more selective than the parent exhibition which opened at the National Gallery in Washington last spring, and it tells a story of serial monogamy in condensed form: from early figurative muralism to throughgoing abstraction, followed by a slow divorce and the embrace of a very different kind of figuration. The show follows the chronology, thankfully, though the notion of a career is less helpful than usual here, and Guston described himself as at no point having a choice in what he produced – if there’s a choice something is wrong – rather as Agnes Martin felt doomed to paint grids (‘My god, am I supposed to paint that?’). As a complication, what the exhibition makes clear is that the later figuration has everything to do with his abstractions, and little to do with his earlier figuration.

The Tate can only hint at the latter, with video and documentary materials, because Guston apprenticed himself as a muralist, influenced by Mexican masters such as David Alfaro Siqueiros and intensely preoccupied by considerations of social justice in action. His works were monumental, site-specific and scattered, and not all have survived. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed him from 1935 onwards to produce giant orderly narratives in which the story of labour unscrolled, at work and play, as an American pastoral. Guston later noted how important it was for a young man to be given a wall to paint, and acreage was suited to his self-taught and stylised virtuosity: statuesque protagonists and steep recessions influenced by early encounters with Surrealist imagery, reproductions of Italian frescoes, Hollywood cinema.

His WPA peers – de Kooning, Gorky, Pollock – served time and then turned gratefully to abstraction. Guston sidestepped the issue by removing himself from New York to the Midwest, where he spent much of the 1940s, slowly translating his procedures from wall to easel, stepping back from narrative and from politics, while teaching at universities in Iowa and St Louis. The effects of the WPA’s brand of social realism on the painters who became Abstract Expressionists is unclear, but Guston retained a lifelong respect for the business of covering a surface with descriptive conviction (as did de Kooning); ‘sign painter’ was a term of praise, early and late.

The figurative easel works in the first rooms at the Tate look dated on arrival – formal compositions of an introspective cast, processing his influences, not least Giorgio de Chirico and Max Beckmann, who was also in the American Midwest during these years. Martial scenes with a cast of uncertain children standing in for grown-ups, caught in poses of dispute, play-acting against backdrops of ‘metaphysical’ porticoes, plazas, chimneys. Years later, recalling Iowa in a letter, Guston ticked off ‘lonely empty squares, “Gothic” City Halls, armouries, big clocks illuminated at night. Railroad Stations. Trains. Soldiers moving around – the war years’: atmospheres that he found replicated in small towns and abandoned warehouses along the Hudson river after moving to Woodstock in 1967. The Midwest confirmed his sense of enigma as low-lying, a property of unlikely places, and established his preference for the periphery. He had a gift for changing tack, with unconscious conviction, and good antennae, with a sure instinct for what he was missing. His physical removals were frequent, and they confirmed rather than caused a change of view.

In Rome in the winter of 1948 he stopped painting altogether, consorted with Italian abstractionists, was perhaps encouraged to think this was where the European past had been leading all along, and in equal measure was put off by the embers of an image-ridden Fascism. At any rate, a phobia took hold: ‘I was very anxious to lose figuration altogether.’ The horrors of war and revelations about the concentration camps had their effect, and there were personal reminders of things seen that could neither be unseen or shown: his father’s suicide, and the rope from which he dangled, or his dead brother’s ruined legs, crushed in a car accident. One version of the return to figuration two decades later – the bandaged heads, the sawn-off legs, the cellar entrances, the piles of ownerless stuff – was as a sudden access of forgotten and discarded material. This included the redundancies (lightbulbs, overcoats, nails, bricks, picture frames) which started to fill up his canvases, in memory of a failing immigrant father who had turned junkman in California. Guston and Saul Bellow were contemporaries, of Russian stock, raised in the same Montreal ghetto, and Bellow’s father also failed at every trade, including junk dealer. Unlike Bellow, who felt able to perform his ‘virtuoso act of integration’ without sacrifice, Guston né Goldstein had changed his name in 1935, for the usual complex of reasons, and began to lose what could not be made visible in his painting. The process was complete by 1948.

When he returned to New York, notions of a self-fashioning beyond the reach of history held much appeal. Guston made do on the edges of Abstract Expressionism, where he wanted to be. The movement was still in flux, and the mixture of extreme attention with few preconceptions suited his speculative habits. He later recalled Morton Feldman saying that for a few miraculous weeks in the 1950s no one knew what art was. Once Guston got going he was tactically alert, rapidly formulating his characteristic image or signature. He saw his tilt to abstraction as a starting over from scratch, rather than an advance, and believed that one’s subject matter might be doubt itself. Hence his decision to paint on unprimed canvas tacked to the wall: rough squares, the edges pencilled in, the focus centred, the margins left to their own devices. He wanted a closer encounter with paint and its resistances, which he called ‘infighting’. Two of the Tate rooms show the results. Grids or lattices of loose strokes, a co-operative of close tones, hanging colours, painterly without being especially gestural. A space without any outside, lovely and available. Guston became the New York School middleman, artist of a floating world whose attributes included his belatedness and slow procedures (six canvases a year), even as the undecideability of his images set them apart from the current varieties of assertiveness in paint. In 1955 he joined Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko and Kline at the Sidney Janis Gallery. By the end of the decade he was a luminary.

In the Tate’s foreshortened version of this progression, Guston soon tires of diffuseness and the following room is suddenly full of emphases: monochrome canvases (late 1950s, early 1960s) in which white is worked into black, wet on wet, so that the surface seems made up of choppy grey erasures. Out of this a black form emerges, uncertainly, because the lattice or matrix of brushstrokes is so uniform throughout. Nonetheless, there is a black floating mass, in canvas after canvas, centre-stage, rather like a head, sometimes two or three heads, seen from behind, ‘very dense and very heavy’, in Guston’s words. The black ‘floaters’ were shown together at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1966. The Tate has just four of them occupying one room – enough to convey their formidable grouped effect and hermeneutic menace. Back views were of abiding fascination to Guston, as images of absorption, or of flight. He spoke to David Sylvester in an interview, in 1960, while jumping ship: ‘What I really want to do, it seems, is to paint a single form in the middle of a canvas … which is after all what a face is.’ In which case, the question becomes: when will these heads turn?

Guston made successful and unsettled abstractions for a third of his career, from 1948 to the mid-1960s. In the Jewish Museum pictures, the pigment is already gross by comparison with his earlier refinements. The build-up of surface, as if paint could continue on its way without colour (he often denied being a colourist), is rehearsing the cartoons to come, already parting ways with his admirers, and the compositions have descriptive titles that yearn openly for narrative.

Guston spoke of wanting a less knowing relation to what he painted, and continually erased what he thought he already knew. He adopted Valéry’s notion that a bad poem is one that ‘vanishes into meaning’. The resistance of the medium and of his abstract materials had seemed like safeguards, but came to seem a repetition of the known: by 1969 he felt that what he saw around him had become genre painting, esperanto, lobby art, and had come to look expensive, however ad hoc its procedures: ‘Every time I see an abstract painting now I smell mink coats, you know what I mean?’ And there was his intimately damaging charge that New York abstraction, for all its self-preoccupation, was needy, over-solicitous of the viewer. Not least his own beguiling canvases. Above all, its freedoms were a cage: ‘There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth we inherit from abstract art: that painting is autonomous, pure and for itself.’ More than one commentator sensed that loss of world was what Guston’s wistful abstractions had been about. If so, he wanted a return to figuration on new terms.

There are several subplots on the Tate walls, which show his preparations for re-entry, notably a series of small oil or acrylic panels depicting objects, closely hung in a grid – just as Guston arranged them in his studio. Each portrays a solitary object (boot, ink bottle, picture frame, lightbulb, cigar, chair, car, nail, window, clock), each sealed inside its heavy outline, against backgrounds of infinite pink and distorted by a strange painterly attention, as though they are really caricatures of things. As Guston said at the time, it was objects ‘that finally became to me the most enigmatic of all’. These things include hoods, the back of a head, a pair of upside-down cartoon legs disappearing below stage. In a later, related group of small landscapes Guston reduces the Italian scene – formal gardens, umbrella pines, fountains – to a grammar of basic shapes, arranged in rows as on a sushi conveyor. He has again dispersed a few hoods, transformed into topiary. All of it is filtered through Guston’s new day-for-night pink grisaille. These small works set out the stall for his figurative vocabulary, an iconography that seemed to arrive all at once. The following rooms at the Tate show some of the often impossible visual sentences he makes with it. What is striking is that the hoods emerge directly out of this object world.

The room titled ‘Hoods’ is a version of the 1970 Marlborough show in which Guston announced his new idiom and took his leave. The six canvases on show are monumental oils – not cartoons, if the latter suggests left-handedness, or a self-consuming topicality. Like most of Guston’s works, they compel attention as compositions from across the largest of spaces. The backgrounds and the passagework are vague and unceasingly active, their continuity of touch complicit with his abstractions. It is the paint that keeps talking. Put differently, if Guston’s abstractions had been full of anecdote, his new figurations were full of formal pictorial intent. A descriptive painterliness is being applied to figurative ends, but continues to suggest abstract ones. In a sense, he became the figurative wing of Abstract Expressionism. None of which has much to do with his earlier work and its cautious formalities, even if some of the iconography (hoods, ropes, whips) overlaps.

The hoods in these latter rooms look hapless, patched and peeled, slits for eyes, hands like gloves, no mouths to speak of (except to smoke endless cigars), locked in a dumbshow of gestures, trying to have identical thoughts. They keep each other company but look in different directions, are together and alone, and wait for something to happen. The horrors are offstage: as always in Guston, there is a sense of what cannot be shown, or has been erased, and can only be gestured towards: ropes instead of lynchings, clubs and sticks instead of beatings. But the props look like props.

Guston referred to this as a hypothetical rather than a narrative world – ‘What if?’ rather than ‘And then’. What if they were to be shown eating, smoking, drinking, plotting, resting, sleeping … The hoods inhabit identical rooms with bare floorboards, naked lightbulb, an empty picture frame, green rug, fringed lampshade, windows which look out at the marching façades of Midtown high-rises, which look in turn like a memory of the desert mesas of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat comic strip, another early influence. Like Herriman’s trio of characters, the hoods live in a world where no one else lives.

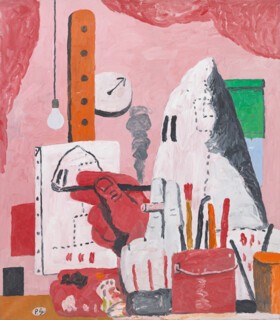

Rather than satire, with a fixed target and a stance beyond, the images tell a sliding story of incrimination, like a series of propositions with undistributed middles. This is a hood – all Klansmen wear hoods – therefore this is a Klansman. This is not a hood – it is a painting, so badly painted that it bears no likeness to a hood. And so on. In one group of pictures, Guston depicted hoods as painters, each flecked with red – which must mean blood, unless it means cadmium red, his favourite colour, which reminded him of pastrami. Food is never far away. The Tate includes the most accomplished of these mises en abyme, The Studio. Here a hooded figure paints another hood, or points at himself, in which case the painter is also the sitter. Pointing and painting are cognate activities in all of the later pictures, which serves to further implicate picture-making. According to the Tate wall text, The Studio indicates Guston’s willingness ‘to ask uncomfortable questions about his own, as well as the wider art world’s, privilege and accountability for society’s injustices’. This is what you tell yourself when you cannot account for the picture’s gaiety and its gusto – without which you cannot access its anxiety.

Guston liked speculation and disliked explanations, and was least forthcoming about those images which were accounted his crudest, or those he referred to as ‘the guys in cars and all that’. The push to establish his alibis comes up against the stubborn satisfactions of his facture (‘real juicy pink oil paint always looks good on a tacky white ground’) and the self-absorption of this cartoon world. If the catalyst for his return to figuration was to be found in the public arena, in the events of 1968, and his longstanding political despair, he spoke only of his joy in their making: ‘I went through the mirror here. And then followed about two and a half or three years of just ecstasy.’ Sean Scully has said that it was only when Guston stopped trying to be high-minded and fell into his authentic personal rage that he became important. Part of the joy is undoubtedly transgressive: whoever paints a hood is a hood. When pressed, he said he painted them because he liked their shape: ‘Who wants to paint a head? What’s nicer than having a hood to paint, and stitches?’

A key intermediary figure is Isaac Babel, who fascinated Guston (on account of their shared Jewish origins in cosmopolitan Odessa, from where Guston’s parents had emigrated to Canada). Babel had joined a Cossack cavalry regiment as a supply officer, and followed the Red Army, which brought such destruction to the Jewish shtetls of Ukraine and Poland. Guston would certainly have known Lionel Trilling’s 1955 essay on Babel, which probed the enigma of a Jew riding as a Cossack. All of which spoke to Guston, riding around town as a Klansman. American violence was his subject (‘The KKK has haunted me since I was a boy’) just as it was for Andy Warhol, or for Robert Lowell, and Guston tried to inhabit it to the point of ventriloquy. Trilling remarked that Babel’s stories were written ‘with a kind of lyric joy, so that one could not at once know just how the author was responding to the brutality he recorded’. Pondering how to depict violence without collusion, Guston was a close student of Renaissance images in which experience is depicted but held at bay by gesture or geometry. Hanging on the walls of his kitchen (‘where you really look at things’) was a reproduction of Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation of Christ, the stilled action in the background – as if in memory, Guston suggested – seemingly unrelated to the unnoticing foreground figures. His own uses of nonchalance reflect a wide-awake sense of the dozing horrors inside public life.

One of the questions for those who were on Guston’s side after 1970 was the seeming excess of his de-skilling. ‘Why did it seem to require such a wide swerve away from Politeness?’ Ross Feld asked, as did Harold Rosenberg in an interview: ‘Why the crudeness?’ Guston replied that it was unintended. He wanted to portray a thing-world the like of which he hadn’t seen, in no way confusable with the world of things. Those not on side suggested that he had become a belated Pop artist. Guston disdained Pop as much as his peers who had seceded from the Sidney Janis Gallery over what he called its embrace of the ‘factual’. But if Rothko and others resigned because of their higher calling, Guston did so because he feared for his own incubating figuration. His facts needed to avoid colliding with their facts. Let Pop have the image repertoire, its mirror held up to a triumphant American reality, and leave him what he called the ‘crapola’. There was an air of stranded anachronism about his new images. It is far from the mock-heroic spirit of the age, even if Guston Pink is mockingly contemporary.

An essential work missing from the Tate show is a small acrylic called Paw. Painted in 1968, it shows what Guston called ‘a beast’s hand’, hairy and uncouth, in the act of drawing a line, as if drawn by the hand that is drawing the hand. The appalling thickset pink render is Guston Crude, reclaiming the right to paint badly. But what comes across in room after room at the Tate is a knowing suavity of touch, all the things his hand could not forget. Guston’s insistence on his de-skilling was the trickiest of his canards. The question abides as to what he learned from de Kooning, the contemporary he especially admired and of whom he scarcely spoke. Followers of de Kooning’s accomplished abstractions in the late 1940s had also been appalled by the sudden appearance of a figure in his canvases of the early 1950s – and what a figure: the snarling and affronting snaggle-toothed sex-toy muse of his Women series. ‘I like the grotesque – it’s more joyous,’ is de Kooning, but might as well be Guston. Here are conspecifics if not ancestors for Guston’s cartoonery, and for its surface volatility of crassness and refinement, which were one response to whatever the age demanded.

After his return to figuration Guston spoke with feeling about abstraction as having cut itself off from language, and of the silent artist as ‘a sort of painting monkey’. His poet-friend William Corbett remarked shrewdly that Guston’s talk about his later work is part of that work. (One of the paintings in the last room at the Tate is titled Talking, a nocturnal contortion of extended arm, crossed fingers and time-piece, juggling lit cigarettes.) There is a corresponding assumption that Guston can be talked about easily, if you empty out the contents of his pictures; and the curatorial commentary has tended in this direction (although the Tate catalogue opens up many perspectives). There is a sizeable library of close readings of Guston – as if there were too much to say.

The later paintings are often inventories, like the coughed-up landscape of Painter’s Forms, in which a human profile regurgitates a bottle, a boot, a shoe sole, a brick, a fragment of easel. Guston lovingly itemises de Chirico – ‘his walls and shadows, his trains and cookies, his mannequins, clocks, blackboards and smoke’ – and we in turn itemise Guston. His compositions ask to be translated into talk. They beg to be parsed. But you cannot describe them so as to sound credible. Thus Painting, Smoking, Eating: a man asleep with open eye below a wall of shoes, smoking and balancing on his chest a plate of French fries that do not resemble French fries. What would that even look like? Works such as Monument – a lonely cairn intricately composed of severed legs and shoes, looking like the Centre Pompidou – in their constant shuffle of attributes and manic duplication (why one pair of legs if a dozen will do) seem increasingly private: self-propelling golems, eating all meanings even as they proliferate, caught between what is shown and what is unseen. But there is no offstage. ‘These objects are not personal,’ Guston said. ‘I am not keeping private meanings from you.’ This seems right: they do not feel like allegories, rather that all the elements necessary for understanding the picture are to be found in the picture, and nowhere else. Which does not help.

The final room at the Tate is suddenly calm and the stage of the paintings vacated. As early as 1960 Guston had spoken to Sylvester of his hope ‘ultimately’ to paint a self-portrait. He now paints himself in the guise of objects, set starkly against a sticky black infinity – Guston as a solitary steaming kettle, as a lit brazier, as a strangely shaped hat – since self-portraiture was the most shapeshifting and mutant of categories. His semblables had included the hoods, and the horizontal cyclopean rolling beanhead who succeeded them, in a host of scenarios, as the painter in bed, an icon of melancholy and paranoia. And it included President Nixon, in the outpouring of pen and ink caricatures produced in 1971 titled Poor Richard, none of which are in the Tate exhibition, regrettably.

Guston paid handsomely for his heresies, peripheral positions and fixation on forgotten things. In 1972 he quit Marlborough and settled eventually with a former Marlborough associate, David McKee, whose new space was (aptly) located in a former beauty salon on the mezzanine of the Barbizon Hotel for Women on Lexington Avenue and East 63rd Street. According to Feld, ‘hardly anyone actually ever bought a post-1969 Guston.’ At one of his last New York shows he sold just a single drawing – but it was bought by Jasper Johns.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.