The invitation said ‘black dress for Ladies’. ‘You’re not allowed to be whiter than him,’ my husband, Jason, instructs. ‘He has to be the whitest. And you cannot wear a hat because that is his thing.’

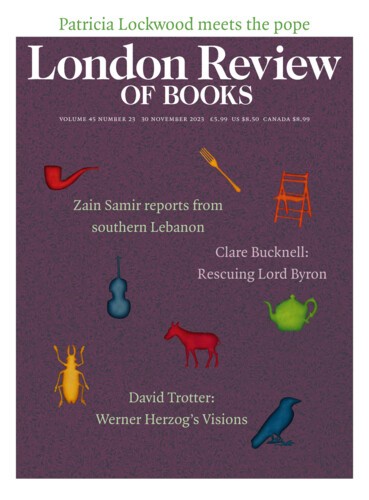

We are discussing the pope, who has woken one morning, at the age of 86, with a sudden craving to meet artists. An event has been proposed: a celebration in the Sistine Chapel on 23 June with the pope and two hundred honoured guests, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the contemporary and modern art collection at the Vatican Museums. I am somehow one of these two hundred; either that, or it is a trap. ‘I think if you’re invited to meet the pope, you go,’ Jason tells me. ‘It will make a perfect ending.’ For what?

Uneasily, I pack a suitcase. My black dress for Ladies might be a swimsuit cover-up; it doesn’t matter. It looks like what a nun who is also a widow would wear to the Y; who cares. Everything has gone wrong, is going wrong. I wake at 6 a.m. on Monday, the day I’m supposed to fly to Rome, and find that Jason has gone to the ER. He has been hospitalised for ileus twice in the past month. Twice in the past week he has got lost on his way home and said strange things like he could feel his brain burning. ‘No, I’m not going,’ I say, when he returns from the hospital with antibiotics, having just drunk something called a ‘GI cocktail’. But he tells me I have to, in the strongest possible terms. He says: ‘I will be upset if you don’t.’

‘Maybe the pope can cure me,’ he says, not entirely joking. The pope, it turns out, is a Bowel Guy. In 2021, he had a hemicolectomy – the same surgery Jason had last August after a caecal flop. Two weeks ago, he was hospitalised with complications. There is some question over whether he’ll even be able to meet us, but apparently the way to get the pope to do something is to tell him not to do it, or vice versa. Jason is very much the same. He is perhaps the person, alone on earth, who would be unaffected by a papal audience. ‘Yeah,’ he says reflectively, ‘if I were there, I would just be like “Hey”.’ Not that he’s immune to celebrity. The actor Bob Balaban once asked him how to use the curl machine at the gym, and he talked about nothing else for the next two years. But the way to get me to do something is to tell me you’ll be upset if I don’t. He tucks his own treasured fanny pack into my bag. ‘All right,’ I say. Perfect ending. I’ll go.

The flight to Rome is sentient; it knows exactly where I’m going and what to provide. At my gate, I find myself sitting next to a guy eating a massive perfect panini. He smells like ten men, perhaps because of the additional paninis he is smuggling on his person. On the phone to his mother, he utters the immortal words: ‘And my sanweeches’. My doppelgänger is on the flight: someone called ‘Aftiola Locka’, whose name keeps being called out over the loudspeaker. She never makes an appearance, though, so possibly she is me, misspelled. When I board the plane, I immediately overhear a conversation about the possible reasons for Pope Benedict’s resignation. ‘I think he was just overwhelmed emotionally and spiritually by it,’ a man sighs, his cardigan redolent of a clergywear catalogue. Across the aisle, naked and rosy, dangles the largest baby foot I have ever seen. I text my friends a picture of it, to give them an idea of the infant’s proportions. King Baby, I call him, and steal looks at him throughout the flight; reassured, protected, in the presence of a monument.

At the airport, I text my Lady’s Companion, my friend Hope. ‘Were you joking when you invited me to come with you to Rome?’ she wrote to me tentatively last week. ‘Hoe, I would never joke about needing another lady to help me stay alive.’ She bought a ticket and immediately began rotating a series of organisational apples in her mind. Hope is an artist and art historian, she has never been to Italy, and much like Jason, she is an optimiser. By the time my taxi arrives at our place – un-air-conditioned, and where we will share a bed – she has already walked seven miles, been to the Pantheon, and sent me a picture of a McDonald’s billboard with a picture of French fries above the word ‘Gnammm’.

I feel I have hardly left the house, or the inside of my own head, since Jason’s surgery last summer. Hope and I have, we have calculated, exactly 72 hours to be tourists. But the elements are against us – it’s 35°C, it’ll be 38°C tomorrow, and I forgot to bring deodorant to meet the pope. So we head to the farmacia, first things first, and buy me an Italian one that somehow makes me wetter than I have ever been in my life.

Here’s the word I cannot remember: ciao. Here’s the thing I should not go around humming: ‘Mambo Italiano’. The website I look up halfway through to see everything I’ve been doing wrong defensively informs me that the one thing Italian men DON’T do is go around singing all the time. I had never heard this stereotype before in my life but it is ALL that I’m experiencing. Sometimes they come up and sing a word directly in your ear. We’re supposed to be offended, but I actually find it valiant, considering the severity of my sock indentations. Then I realise it’s all for Hope: in the US, she is blonde, but here she is gold. She looks put into her portrait. I guess it’s how I would look peeping out of a Basque cave. Still, I have my admirers. At one point I become entangled with an Italian waiter to such a degree that he shows up at our table with a full quarter of a watermelon. Then he makes me eat all of it. Italy rules.

I JUST SAW A PRIEST IN BLACK JEANS, I text Jason, almost hysterical. Imagine how different my childhood would have been if it had been populated by priests in black jeans. He is an emissary, like a seagull near shore, because moments later Hope and I turn into an alley and find ourselves, dazed and swivelling, in the priest fashion district, in front of a shop called Gherri. The windows are full of chasubles, albs, monstrances, amethyst rings, silver patens, violet socks. Scattered here and there are bags of wafers. This is a chance to set up the photo shoot I have always dreamed of: me in the bathtub like Whoopi Goldberg, covered with unblessed hosts. In the end, though, I am too shy to enter. Knowing what I know – of ambition, fondling of crosiers and will to power – Gherri is too close to nakedness: it is like a lingerie store.

My understanding of Keats is that the Spanish Steps personally threw him down. I do not wish to strip Hope of her illusion that I have a deep knowledge of, and a passion to appreciate, Rome’s literary history, so I keep this to myself as we wend our way to the Piazza di Spagna. The stairwell of the Keats-Shelley House is hung with sketches and lithographs of Englishmen perishing in a palm-tree climate, the lines fine as human hair. ‘Did you know George Eliot’s husband KILLED HIMSELF on their honeymoon?’ I say gaily in the gift shop. This is not true! I had just got too hot! This becomes clear when I start crying at the informational video, which juxtaposes stiff ambassadorial footage of King Charles talking about his nonna with a female voice intoning: ‘She stood in tears amid the alien corn.’ I’M in the alien corn! The effect of poetry is reliable, still. Your skin gets a whole size smaller.

Upstairs, I walk past the life-mask, with its visible eyelashes and long muzzle like a deer’s, into Keats’s room. A plaque informs me that the bed is not original; after his death, the Vatican ordered everything to be burned. ‘How long will this posthumous life of mine last?’ Keats demanded in this place every morning, before the Spanish Steps tumbled him. But there is something live in the room, a loose red tile in the middle of the floor like a tooth, so that when you step on it you lurch forward and go ‘Whoa! Hey!’ That is the picture I take, for some reason, my aching foot pressing it down.

From there, we head to the Capuchin crypt. My Tyrolean mountain climbing outfit is judged too revealing, so I am asked to tie a sort of barber’s cape around my waist. ‘Just the waist!’ the man yelps, when I try to put it around my whole body; I’m not going to cheat him out of an arm view. Downstairs, I start my period immediately while looking at an illumination of Christ as a sausage, coming violently uncased. I contemplate the bloodstained sheets of the stigmatic Padre Pio. But really we are there for the 3700 corpses, for the monk patience, bordering on madness, that assembled them into their tableaux and proximities and pinwheels. The Barberini princess stays flying on the ceiling, now swinging the same scythe that struck her down. Some people find it awful, and some find it funny. ‘It is funny,’ I say aloud, in the Chapel of Pelvises. One woman was so devoted to the Capuchins – she loved comedy – that she asked to have her heart buried in the wall, where it beats.

Those six words every girl wants to hear: an Irish bishop is sponsoring me. He finds us at the welcome party on the second night at the Vatican Museums. Afterwards he takes us out to dinner, where I somehow, and to his grave disappointment (he had recommended the pasta), order the deepest salad in the world. There is literally no bottom to it, like mercy. What are we doing here, exactly? ‘What is this?’ I ask the bishop at one point. He answers with the question that inspired the whole event: ‘Can we be friends again? The Church and the artists?’ I feel a deep bodily tug, somewhere near the bottom of my salad, into the kind of conversation that I know so well. Pretty soon I am going to hear a Bible quote. Then it happens, and when the bishop says, ‘Who do you say that I am?’ I begin to cry. ‘But I’m not sure we should be friends,’ I say to the bishop. There is a connection that is more intimate and probably more true. I think they should burn everything in my room when I die.

I wake in total darkness, certain that I am about to see the sunrise over St Peter’s Square. It is 1.27 a.m. I call Jason, who sounds a little better after his GI cocktail – more coherent, at least, than he did yesterday. Then I hang up, feeling the swell I do when clouds are moving in, and begin to assemble my notes.

‘We are writing about it,’ I told Hope at the very beginning. How do you do it? You find some sort of frame, or an occasion for pattern recognition, and the corresponding colours fall into your hands like gems. You might step through a doorway and find anything. Yesterday we walked into a random basilica that housed the body of Catherine of Siena – well, everything except her head. ‘The people of Siena wished to have Catherine’s body,’ I learn. Don’t we all.

Knowing that they could not smuggle her whole body out of Rome, they decided to take only her head, which they placed in a bag. When stopped by the Roman guards, they prayed to Catherine to help them, confident that she would rather have her body (or at least part thereof) in Siena. When they opened the bag to show the guards, it appeared no longer to hold her head but to be full of rose petals.

This is constantly happening to me.

But what is more difficult to explain is the way the pattern pulls people and dialogue towards it as well. Sometimes it even seems to create them. This is another reason to write essays – during the period of composition the world does nothing but give you gifts.

They love David Foster Wallace here, and I have read no one but him for months. His books are everywhere in tall voluble stacks – a writer is always everywhere when you are working on them. I feel partially disrobed when I see his name. At my sickest, I had begun asking myself, from the tall throne of judgment that is the piece, what are we doing? Why are we writing about people this way, as if we are sifting their souls? I feel as if I’m wearing Wallace’s sweatband. At the English-language bookshop Otherwise, we make friends with the man behind the till, Donato, who poses for a picture while exclaiming: ‘I’m ugly as fuck though!’ He has excellent taste in literature. He gives us a free tote bag. On the back of it is printed: ‘Good fiction’s job is to comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.’ I have the chance to do the funniest thing possible and carry this into the Sistine Chapel.

Today Hope is walking around with one giant David Bowie pupil, the better to see Italy with. We are looking for gifts and, in particular, a rosary for my mother. We find nothing until in one shop we find everything. In the front window hang glimmering tin and silver body parts – ex voto. Hope buys a leg for her father, a mouth and throat for herself, and for her mother, an entire little girl, intact. ‘Do you have any rosaries?’ I ask at the last minute, while Hope is on the phone to her credit card company, which is cruelly trying to prevent her from buying more appendages. ‘Just these,’ the woman says, opening the glass case I’ve been leaning on, and lifting out some old, old garnets for the recitation of the Seven Sorrows. They are almost black, and their facets have been clashed into a kind of glitter; where a cross should hang, there is an empty reliquary in the shape of a heart. I had been staring at them for a long time without knowing what they were. ‘Yes, I’ll take those. And the torso,’ I tell her, pointing to the window, where a little tin belly button winks in the afternoon light.

At dinner with the bishop, we had mentioned that Hope couldn’t get a ticket to the Sistine Chapel. Can you help us with that? we asked him. ‘I’ll see what I can do,’ he said. I thought this meant that he would scrounge one from somewhere. Instead, Hope says she’ll just come with me tomorrow morning and see if they’ll let her pop in for a minute. But this, because I am a tiny blind mole with my nose pressed to a copy of the rules, worries me. What if I’m accused of trying to sneak her in? What if I get yelled at, and then find myself unable to experience my moment?

The museum is surrounded by a huge wall, so it’s like entering a mountain. People, even very early in the morning, wait in long snaking lines and we slip past them, embarrassed. It is a childhood feeling, walking to the front of the church and straight into the sacristy: my father is here, getting ready for the show. ‘I know she can’t come in,’ I say to the bishop when we reach him, making a weird stop sign with my hands, and in turn he makes a gesture of smoothing the waters. His presence is comforting. Somehow it is easier to believe in Jaysus. ‘Let’s just see what happens,’ he says. Imagine an Irish Catholic bishop telling you that you have no chill. A woman with a clipboard looks for Hope’s name and then apologises profusely. ‘No no no,’ I squeal, a little rulepig, but she finishes: since she’s not on the list, she will have to stand at the back with the journalists.

Before leaving that morning, we stuffed my bag with all sorts of objects, reasoning that if the pope blessed me, anything on my person would be blessed as well. It now has to go through the metal detector, a tense moment. I wonder what security will make of it – a jumble of legs, jaws, little girls, torsos and precious stones, all awaiting the gesture. How far does the principle of a blessing extend? Because there’s a tampon in there that going forward I will hesitate to use.

We walk down winding stone stairs. I am conversing with an Australian conductor, the first woman to conduct the Vienna Philharmonic. ‘So you’re Tár,’ I say thoughtfully. No, she actually is Tár. Suddenly we are in a dome that feels like a human head, full of flesh, climbing like ivy. But there is something strange: I see the old scaffolding, as if it is still in progress, and I see the paintbrush raised. That weirdo is still up there, Michelangelo. He’s still going. The light is brutal for people but lays the art bare.

‘Are you Ken Loach?’ I ask politely, of the male flamingo seated next to me. ‘No,’ he says, chuckling, he switched seats with him. His name is Ross Lovegrove, he is Welsh, and the burr comes right up from his breastbone. He tells me who everyone is. We talk about voices, beards and great moon-faced Welsh actors. He has been to the Galápagos with Richard Dawkins. I almost ask, why? He says if Shakespeare had been born on a beach we would never have had the plays. Well, we would have, but they would all be called things like Pleasure Hammock.

I twist around and see Hope making friends with a brisk-moving young Portuguese priest. He is taking a picture of her? She wore her black jumpsuit that morning, so she fits the dress code for Ladies from the ankles up, but she alone in the Sistine Chapel is wearing Birkenstocks. ‘That’s what she should be wearing,’ Ross says, with a granitic nod. ‘You know who else wore sandals.’ ‘What are you?’ I turn on Ross with sudden bluntness. He twinkles down like a piece of human bismuth. ‘You could call me … an architect of technology,’ he tells me. What’s that? Oh, it seems that he has designed a chair. That I can understand.

When the pope is rolled in in his wheelchair, everyone takes the same picture. This doesn’t seem right – shouldn’t your first encounter with the pope be primary? But then this is a room full of artists. I wonder what it is like to experience this visually, rather than whatever I’m doing. We are there as ourselves, but also as what we do. What is André Rieu feeling right now? Something in his baton? Is Rem Koolhaas hearing a strange buzzing in his building? But I feel myself here not as a heart in the wall, or a longtime practitioner of monk patience. I’m here as the caretaker of a Bowel Guy.

Someone is playing Bach on a cello made from the wood of Greek migrants’ boats. We have a programme containing the pope’s address in English, but I’ve only glanced at it to see a quote from Romano Guardini comparing artists to children. The cellist finishes, the pope begins. His speech, since I am looking at him instead of following along on paper, seems to consist of three words, repeated over and over: Bambini. Morta. Che bella. ‘Che bella’ comes out with his old strength of voice, so beautiful.

There are dark rumours of a woman with her midriff showing, and of a guy who runs around taking selfies and posting videos of the pope as he goes. This all seems in order to me. If my current self were here, perhaps I would be streaking down the aisle screaming FIGHT THE REAL ENEMY and CATS HAVE SOULS! But that’s never been my method. I streak around later. I have a brief moment of panic. Is it wrong to meet the pope? Then: if Martin Scorsese did it, it’s probably fine.

The photographer Andres Serrano is tall and his look is pastoral. His colour is mild and his eyes look like two skips of a stone across the water. This is not true in pictures but it is true in person. He walks through the crowd like he is looking for someone, another even taller man. When he approaches, the pope makes a little fake-mad face and then gives him a thumbs-up and a smile. This is what irreverence gets you – the frankest love of all. It is real but it is also canny, presenting a coprolite to the photographers as a gem.

Everyone is giving him things. This, to me, seems crazy. Why would you give something to the pope? He has like four things, and one of them is God. Imagine if I kneeled down in front of him and presented him with a critical essay about his 2015 prog rock album titled ‘Notions of Sleep and Alertness in Bergoglio’s Wake Up!’ Actually, one guy does get down on his knees and then sets off a wave of other people all getting down on their knees. I guess that’s how the whole thing started in the first place.

It’s easy to pick out the Catholics (or former Catholics) because on the way back to their seats, they look vaguely like they’ve eaten something, like they’re returning from Holy Communion. Gnammy. Will I look that way? It hits me for the first time that I have to speak to him. I haven’t rehearsed this, haven’t thought about it at all. I pull up my socks like a second-grader and step into the line. Nearer and nearer … a flamingo kneels down … something is taking a rather long time. Oh, it’s Ross giving him a drawing called The Quantum Eternity of Love.

There now exist, in the world, several official photos where I appear to be cursing the pope in ermine language. As well as an image of his attempt to wrench his hand from mine, because when Ross stands and I walk forward to meet him, I glitch. I tell him my name, which seems untrue. ‘I hope your stomach feels better,’ I say, insanely, pointing to mine. Possibly I even say tummy.

A bit of weather crosses the pope’s face. He’s mad at me, maybe, for not giving him a drawing called The Quantum Eternity of Love. No, he’s mad at me for not giving his hand back. He retrieves it, with surprising strength, and then raises two fingers and blesses my stomach. He is finally smiling – no longer trapped with the artists, but back with the bambini. Oh my God, I realise, as I walk back to my seat, he 100 per cent thinks I am pregnant.

In my uninvented chair, I rearrange my nun-like folds. I am shivering, like my pandemic nephew when he saw strangers for the first time. Ross respectfully squeezes my knee to comfort me. At this moment, and at other times as well, it is the biggest knee in the world. ‘What did you tell him?’ I ask, when my teeth stop chattering. Ross, as if it were obvious: ‘I have love in my name so love is everything.’ He then adds, not quite irrelevantly: ‘My parents were first cousins.’ Let every chair that was not invented by this guy break instantly under my ass for the rest of my life.

I turn. Hope is walking down the aisle, my bride. She is going to meet the pope, she is one of the artists. The moment could be anything – and is so much easier to hold when it is someone else’s. Jason will order a picture of my moment from the Vatican website, choose the largest version just to be sure, and receive something the size of a movie poster where I appear to be bitching out the primate of Rome.

Afterwards Hope and I walk through another hall of human heads. The air inside the Vatican Museums is a whisper, of inside information, yes, of history, yes, but even more of that alternate reality, the parallel track that when you enter it carries you alongside life. ‘Small dick equals big brain,’ Hope says knowledgeably, indicating one statue; she is absorbed in her own parallel track. We take a picture of an enormous marble baby flexing his little muscles. Tiberius has a daddy-long-legs hanging from his right ear. Marble, onyx, alabaster. Alabaster is a stone of great penetration: eyesight, light and time all go knocking at the heart of it.

At the reception – no, excuse me, the ‘vin d’honneur in the Lapidary Gallery’ – they are serving wine from Sting’s vineyard. ‘What did you say?’ I yell at Hope, who is flying on a single glass, and she points to a brochure from which Sting stares out with a look of intense fermentation, Trudie’s arms wrapped around his chest from behind, both of them wearing the honey of great good health and presumably fresh from a seven-hour stomping. I guess the idea is that you meet the pope and then get a mouthful of Sting’s grapes. I nod to the brochure and Hope nods back conspiratorially, slipping it into her bag. That is how it is done; we are doing it. The Vermentino, yes, is called ‘Message in a Bottle’. So is the Sangiovese.

‘Do the priests … flirt with you?’ Hope asks hesitantly. She is what is referred to as a ‘grey ace’, so she actually doesn’t know. ‘Oh yes,’ I say, PLEASURED to jump in. That’s not always the word for it, but sometimes it is. Sometimes it is camp – you know when the guy doing the wine-tasting flirts with your mom? Sometimes it’s like stepping into the tiniest club in the world: we know what we are, and Carly Rae Jepsen is playing; we bounce together in a kind of unison. ‘I don’t know, I just … I like guys,’ a lesbian once told me, when I asked her why she always had big dogs. Exactly my feeling in the presence of priests.

The garnets are so heavy in my pocket. Suddenly I want to keep them, I don’t know why. More often I am prone to giving possessions away. But the dolour of the garnets is so mellow, and it is so full of old feeling, long laid to rest, that I cannot help myself. Whose garnets, whose grief had it been? The sharp facets touched into a kind of velvet – what I really wanted was something almost human, which had clashed with itself for so long a time.

What if the pope cured me. Ha ha, but what if. I am flying another body alongside me, in the air, at shoulder height – it is not unlike religion. Keeping him up like the plane, across oceans. Ribs and piercings and the round red drop. And rose petals instead of a head, for believers.

What I might have asked the pope is, are you false? Do you ever feel yourself to be false? Does your name ever feel untrue, Francis? As you became larger and larger, did you feel yourself becoming smaller and smaller? Are the words ever strange in your mouth? Do you ever shake in this place? Can a blessing fly through you to someone else’s belly? Who gets to be different, who gets to be bigger, who is allowed in? Who do you say that I am?

What is blasphemy? ‘I want the pope’s blessing,’ Andres Serrano said in an interview. ‘I am a Christian.’ If you give Serrano’s Immersion (Piss Christ) to students without telling them what it is, Hope told us that night, twirling her pasta, they will talk about the colour. Grading red from the edges to the centre, where the face drooping forward from its plastic crucifix is struck with piss and light.

Ithought we might rest afterwards, but Hope is determined to see everything – in addition to the pope’s juice, she is still experiencing Sting’s wine. We’ll ride the Metro to the Colosseum and then take a bus from there to the San Callisto catacombs. ‘I know that the proper thing to do, when you get to a village or town, is to rush off to the churchyard, and enjoy the graves,’ Jerome K. Jerome writes. ‘But it is a recreation that I always deny myself.’ The art historians among us are not so austere.

A few minutes into the Metro ride a series of teenagers rush into the carriage and hug us and lean on us and sit on our laps. The girl next to me is holding my hand. When I look at her she rolls her eyes at me heavily – like I just asked her if she was a Belieber. What’s going on, is she my daughter? She flops her coat over my arm and I begin to experience a sensation that I can only describe as being invaded by a school of eels. Looking down, I am idly touched by the label; the coat is identical to the one I have from TK Maxx. It’s 36°C, isn’t she hot? I shift my grip on the pole and silently apologise to her for my Italian deodorant. Something tugs at the zipper of my fanny pack and I angle my hips away. Over the girl’s head, I send a message to Hope, but since I have no idea what’s going on, I’m not sure what the signal is supposed to mean: eels? ‘What was going on with those weird children?’ I ask, when the doors release us and the girls go bounding past us up the stairs. ‘Oh yeah, they were pickpockets,’ Hope says. ‘Did you not … wait, was it happening to you?’ Pickpockets, I repeat, the word rolling out of my mouth as if for the first time. ‘Did they get anything?’ she asks. ‘I don’t think so,’ I say, patting myself down – what was in there anyway, my keys, my money, my identity, my garnets? ‘Oh no, they’re not getting in there,’ Jason says peacefully, when I tell him about it later. ‘Those are triple-reinforced camping zippers.’

I am unsettled on the bus, still feeling the fingers. There’s a better encounter we might have had that morning: the pope and I sit in a room with our possessions, and the girls of the world come and rob us. When we reach our destination we are taken on the least educational tour of the San Callisto catacombs possible, during which the tour guide ushers us past everything worth seeing, opting instead to show us a series of holes while reiterating that early Christians believed in the Resurrection. There are too many people jostling for space, all stumbling on one another’s heels in the dark – either a flashback or a kind of preview. In mad defiance, Hope gets lost trying to find the mosaics, and appears twenty minutes later with a guy who looks like the Little Caesars mascot; he seems to be experiencing this descent into the grave as if it were a slice of pizza. To deflect from their rebellion, he asks the guide whether any of the bodies were buried with ‘riches and dowries and, say, treasure’. The guide stares at him for a moment with patient hatred, then indicates an empty hole and repeats that early Christians believed in the Resurrection. We climb up out of the earth and into the air again. An entire tour bus of Croatians files past us, singing their national anthem. They are having – maybe always – a much better time.

We eat potato chips from the gift shop, which sells postcards of a laughing Francis literally hurling doves from his hands, and look out through the haze. The trees seem combed forward, like Byron’s curls, under a layer of blue and gold two-dimensional dust. Do you think there’s more haze than there used to be, I wonder – considering that the Earth, our home, is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth? Hope considers it, the fresco light on her face. No, I think it always looked like this.

The last night, we meet on the terrace of a pope-themed hotel – no, seriously, there is a portrait of John Paul II outside the bathroom, caressing his left cheek like an author. The writers are there, and a handful of artists, and Ross and his partner, Ila. Halfway through – I’m not sure how it happens – Hope and I find ourselves at the end of the table with Ila, absolutely screaming about something called proxemics: the study of human bodies and the way they relate to one another. ‘Oh, this is what I like!’ I cry. I didn’t know there was a word for it. Our knees grow closer and closer, until we create a kind of star. She has excellent boundaries, she says, but Ross is an amoeba like me, he just goes into people at parties and then collapses when he gets home. That’s why it’s necessary to create new kinds of chair, I guess.

It is still strange to be crushed together with other people. The last three years were like the modern idea of hell: no fire, but cold distance, abandoned to become more ourselves, sound more like ourselves, think more of our own thoughts. We are talking about AI: Ila lives in the future. We talk about hallucinations in the machine. I read the poem a chatbot wrote about my cat Miette, which ends with a line about ‘a twinkle in her biz’. (This was in that two-month period when playing with chatbots was kind of fun, not a contribution to the decline and fall.) ‘Here’s where it begins to go weird,’ I say, when it starts talking about ‘the flick of her lights’. If the AI can have accidents, if it is subject to errata, then it can create poetry, which is also a kind of glitch in what we know. When I walked into the Sistine Chapel, what I felt was terror, as if the sum total of what I knew was in that place, and I was experiencing it all in a moment. A sunset like the long lowering of a robe is behind me, my back is to a row of human statues. ‘We must make friends with it,’ Ila says, as our knees grow closer and closer. Little fingers everywhere, reaching. ‘The Singularity is coming,’ she says. We won’t know the moment – and as always, there are those who say it has already happened.

This is how it is done. Appoint a representative – King Baby, for instance – and he will go out into the world and gather details for you. Mostly he will recognise other things of his kind: the Barberini princess swinging her scythe on the ceiling, the marble boy with his little muscles. The autograph I give to a girl on the plane ride home, on the back of the Baby Care bag.

The girl does not know who I am, of course. But she asks what I do, and I tell her. She is from Covington, Kentucky, across the river from where I grew up. She had four years of Latin in high school and it’s her job to make tractors look sexy. She is Catholic, and goes to church every Sunday even though it is ‘so hard’. She has served a bishop, and gone about among good and bad seminarians. In other words, she steps into the frame as if it were her portrait.

Our subsequent flights are delayed – a man has been ingested into an engine in San Antonio, though we do not know that then – so the girl and I meet again in Tigín, the Irish pub in JFK, where she speaks of a man who had stigmata that could not be explained by either her dermatologist father or her dermatologist grandfather. She asks about the background photo on my phone. I tell her it’s my niece, Lena, who passed away, and then gently steer the conversation elsewhere. But she asks about her again, a minute or two later, and then I am crying a little in the Irish pub, telling her how it made my sister so much taller, so much bigger than me. She wants to hear everything, which is not true of everyone but is true of the kind of person I used to be. ‘I believe your niece, Leia, is in heaven,’ she says. A lovely mistake, in the raw now. King Baby pointing to another of his kind.

Under some blue dome it is all still happening. The raw now is where your elbows live, and your bruises, and your socks slipping down your ankles. It is what cannot be recovered later; the strap of your bag that has flopped over your grave Italian seat mate’s programme; the fear that you have left the sound on your phone on; a text from Hope: ‘You’re about to meet the pope!’ It is the point, probably, of the hair shirt and the cilice that we saw in the Capuchin crypt. Your awkwardness, the edge of confusion, irritation, pain, incomprehension on the pope’s face as you approach him, your hand circling your tummy, clashes of bodies, like beads against one another, which will be worn smooth over time.

The time passes like nothing, like clear girdle-blue water. Nudity billows and purls all over the ceiling. It is like flesh in clouds, or falling in rills over stones. Kneecaps, elbows, scapulas. It is resting me, I am tired. I am here as an earlier self, who knows how to sit in rows. I have body parts in my bag, detached and jumbled, for the blessing. I am ill in myself and my beloved and the world, and I am listening for the breathing of someone who has lived a small part of my life. You know you saw Sinéad O’Connor’s hands trembling when she ripped up that photo on Saturday Night Live as my chin trembled when I walked into the Sistine Chapel. Shaken by the sum of something.

‘Can we be friends?’ the bishop asked, of the artists. I don’t know. The fingertips reach forever, just above my head. I count beads in my pocket. If you recite the Seven Sorrows faithfully, they tell us, when you die, you will see the face of your mother.

How is it done? You can write about these things and still not be any the wiser. ‘You are children,’ the pope tells us, in his baby hat. When I go up to meet him, my body parts shining, I am calm, because I have thought of the right way to describe him. ‘When they roll him down the aisle, he goes over a bump, and makes a little face like “Whoa! Hey!” He looks like a baby when it sees something it likes, when something very bright has been held in front of it. A ring of keys.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.