The painter Cecily Brown offers a short biography on her website: ‘Born in London. Lives and works in New York’. But there is more to her than that. Her mother is the novelist Shena Mackay; her father was the art critic David Sylvester, though she thought of him as an ‘uncle’ until she was 21. She took life drawing classes at Morley College in the late 1980s, which brought her to the attention of Maggi Hambling. A garage belonging to Hambling served as her studio as she built up a portfolio for the Slade. Brown graduated in 1993 and moved to New York the following year. She is now 54, and her work is the subject of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a rare feat for a living artist.

Brown’s early paintings, of cavorting, scheming bunny rabbits slipping in and out of whorls of colour, were, in her own words, ‘highly charged, frenzied spectacles involving orgiastic rituals with an element of black comedy’. Her first solo shows, at Deitch Projects in SoHo, were put on by Jeffrey Deitch, a pinstripe suit-wearing former Citibank art adviser. In 1999 she signed with Gagosian. Her ascent had been rapid and it was crowned in 2000, when she was photographed for Vanity Fair lying in front of one of her paintings, wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with a dollar sign. For some critics, it was all too much. Adrian Searle, writing for the Guardian, complained about the ‘fuss’ over Brown, which led inevitably to disappointment when confronted with her paintings: ‘The energy flows out of me as I look at them, searching for faces, body parts, the reason behind all the painted drama.’

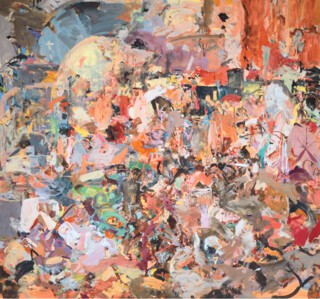

‘Painted drama’ is a useful way of thinking about Brown’s method, which seems to proceed by intuition. Work of this kind is inevitably uneven, but the theatre may still be something to relish. Her paintings invoke turbulent and transgressive sensory experiences – they seem to come in and out of focus, slowly revealing recognisable details. Looking at her churning surfaces, I was reminded of Hannah Sullivan’s poem ‘You, Very Young in New York’: ‘you have been sleeping through a rainstorm,/Half aware of the sewage and frying peanut oil and the ozone/Rising in the morning heat.’ There is noise and flavour here, smells and images and something harder to define – atmosphere, or atmospheric pressure, the heaviness of heat and rain on a mind still half-asleep. Brown conjures a similarly porous sensuality.

Willem de Kooning wrote that flesh was the reason oil paint was invented and Brown seems to revel in the pliability of her medium, its viscous and tactile surfaces. In 2007, The Pyjama Game (1997-98) went for $1.6 million and a decade later Suddenly Last Summer (1999) sold for $6.8 million, making her one of the most expensive living female artists, alongside her fellow Slade graduate Jenny Saville (another painter of the flesh and its appetites). The Met offers a welcome counterpoint to Brown’s previous showings in white-walled commercial galleries. To reach the exhibition, you pass Chaïm Soutine’s The Ray (1924), in which the bloody entrails of a grinning fish spill onto a tablecloth laden with apricots. Soutine made the painting in response to Jean Chardin’s Rayfish (1725-26) and Brown’s work leaps easily into the fray.

Death and the Maid (until 3 December) surveys Brown’s paintings in the vanitas and still life traditions. Some are graphic in their figuration, such as Hangover Square (2005), which suggests the domestic abandon of an alcoholic; others are looser – The Only Game in Town (1997), for instance, in which a woman gazes in horror at her monstrous reflection in the mirror. There are nearly fifty works altogether, hung in one large room painted a lichen green, which works as a clever accent to the lipstick pinks that recur in Brown’s work. It is a shame not to have any benches, as these pictures grow more interesting the longer one looks. Denser compositions, such as Carnival and Lent (2006-8), inspired by Bruegel’s scene of the same name, are teeming with detail, but even Brown’s simplest compositions offer much in the way of allusion and visual intrigue. This is a painter who has gorged on the history of mark-making.

The Met exhibition has caused some of Brown’s critics to repent. A New York Times review ran with the headline ‘I was wrong about Cecily Brown.’ Has the change of setting made a difference? Or is it just the passing of time? Her commercial affiliations, the gossip of auction highs and art fairs and representation, all seem remote in Room 913 of the Met. Given this, the curators might have made more of the work’s uneasiness and ambivalence. It’s not hard to praise Brown’s ‘bravura brushwork’ and to point out the art-historical precedents and motifs. What’s more difficult is to define her work’s relation to our own carnality, to the opulence and squalor of our daily lives. As an artist formed within – some have claimed by – the contemporary art market, Brown has much to tell us about its frenzy and excess.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.