Writing of Ruth Asawa’s first solo exhibition in New York in 1954, the critic Parker Tyler described her sculptures as inviting the viewer ‘to be as still as they are or to tremble when they tremble’. He was responding to what had become her signature works: biomorphic forms woven from industrial wire, hung from the ceiling like lanterns. The first of these on display at Modern Art Oxford’s retrospective (until 21 August), the bronchial Untitled S.052, was made in 1965, the year that MAO opened. It hangs at the top of the stairs to the main gallery; a further eighteen wire sculptures hang inside, some tall and closely gathered, like drifts of towering poppies, while others – smaller, spikier – float alone.

Asawa first experimented with wire forms in the summer of 1947, after watching a Mexican craftsman in Toluca make baskets for storing eggs. She liked the simplicity of the looping line, and wire was cheap and plentiful at a time when art materials were scarce. Her parents had emigrated from Japan to the US, and Asawa was born (as Aiko) in 1926 in Norwalk, California, the fourth of seven children. They worked on the family farm every day after school, growing vegetables to sell at the local market.

Their lives were upended in February 1942 when Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorised the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast. (The word ‘internment’ is common but misleading, since two-thirds of those detained were US citizens like Asawa and none was convicted of espionage or sabotage.) FBI agents arrested her father, Umakichi, who was sent to New Mexico; in April, Asawa was taken, along with her mother and five of her siblings, to the Santa Anita racetrack in Arcadia, just outside LA, where they were housed in converted stables. ‘The smell of horse dung never left the place,’ she later wrote. The curators of the MAO show point to this difficult period in the second room of the exhibition, which contains a poster from May 1942 with ‘instructions to all persons of Japanese ancestry’ to report to a Civil Control Station, and a vitrine featuring Asawa’s Relocation Authority identification card, with a photograph of her aged seventeen. The camp was also the site of an unlikely initiation. Among the other detainees were three Disney illustrators – Tom Okamoto, Ben Tanaka and Chris Ishii – who taught art in the bleachers of the old racetrack.

These classes inspired Asawa to apply to Milwaukee State Teachers’ College, and in 1943 she was granted leave from the War Relocation Authority to train there as an art teacher. She left without a degree after being told she couldn’t complete her final placement because of anti-Japanese sentiment. A fellow student, Elaine Schmitt, encouraged Asawa to join her at Black Mountain College, where she spent the summer of 1946, securing a scholarship to stay on for three more years. The experimental environment of the college offered ‘enough stimulation’, she later wrote, ‘to last me the rest of my life’. It also brought her a boy from Georgia called Albert Lanier, who arrived on the GI Bill to study architecture in the autumn of 1947 and proposed to her within a year.

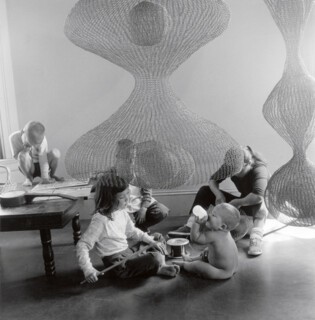

Asawa and Lanier decided to settle in San Francisco in 1949 after hearing that you could get a five-course Italian meal in North Beach for 75 cents (this turned out not to be true). Albert got a job with an architecture firm, and they had six children in nine years – Xavier, Aiko, Hudson, Adam, Addie and Paul. Asawa found a way to work alongside them, as the photographer Imogen Cunningham illustrated in a series of portraits. The two women had been introduced by Cunningham’s son, Rondall, in 1950, and remained friends and collaborators until her death in 1976. In an image from 1957, Cunningham shows Asawa absorbed in her work while her children play around her – one of her sons crouches on a table, his head down in studious imitation of his mother, while two older children sit on the floor beside her. A naked baby feeds from a bottle of milk. Partly obscuring the family scene are two looming sculptures.

‘I like to be surprised by a nectarine that is no longer a nectarine,’ Asawa said of her attraction to certain organic shapes. ‘I like nectarine, apricot being put together.’ She had happy memories of her childhood on the farm. Reflecting the multi-disciplinary ethos of Black Mountain, the final room of the exhibition displays her drawings, paintings, prints and designs. Natural forms rendered in one medium often fed into another: the skeleton of a desert plant given to her by a friend prompted a bristling, wall-mounted, ‘tied-wire’ sculpture, a simplified work in ink on paper, and a large-scale mosaic for a public commission.

Asawa’s attraction to natural geometries was partly influenced by Buckminster Fuller, who joined the faculty at Black Mountain in 1948 with, as she put it, ‘his magical world of mathematical models packed in an aluminium trailer’. Asawa took his architecture and industrial engineering classes and watched as he constructed the first of his geodesic domes (he liked to suspend students from the ceiling to demonstrate its resilience). Her most complex wire constructions, such as the untitled seven-lobed sculpture in MAO’s first room, which she gave to Fuller in 1961, she considered sculptural expressions of his belief in the fundamental interconnectivity of life on ‘spaceship Earth’.

Citizen of the Universe is the first museum exhibition of Asawa’s work outside the US (it will travel to Norway’s Stavanger Art Museum in the autumn), but she has not been neglected at home. A print she made using cascading lines of ‘BMC’ laundry stamps became the cover for the official Black Mountain brochure in 1949, and later a fabric and wallpaper design; she exhibited throughout her lifetime, with her first museum show in 1960 and her first retrospective in 1973; and the inaugural issue of Artforum claimed that her ‘economically stated works are surely among the most original and satisfying new sculpture to have arisen in the western United States’. In 1982, San Francisco established a ‘Ruth Asawa Day’.

If her work has been admired, however, it has sometimes come at a cost to her philosophy. Asawa’s statements about the therapeutic nature of art-making are usually glossed over by curators, as is the proximity of her work to traditional handicrafts. By contrast, the MAO show grounds the sculptures in her wider practice and principles. She didn’t see herself as an activist – although involved in many campaigns, she preferred ‘to be working on an idea’ – but the serenity of her works wasn’t supposed to be enjoyed at one remove from their making. In 1963, on a visit to C&M Plating Works (the company that cleaned and oxidised her sculptures), Asawa noticed the encrusted copper bars used to remove tiny imperfections from car bumpers. She asked if it might be possible to reverse the electroplating process to make new growth appear on her copper wire sculptures. The platers complied, and the idea led to a short series (small examples are included in the show), which speaks to her enthusiasm for process and the calligraphic force of her ideas, traced from dry cactus and chrome bumper to magisterial, spectral sculpture.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.