One of Kate Beaton’s more famous illustrations features an unlikely protagonist for a cartoon strip: Nikola Tesla. In Hark! A Vagrant, a comic published online between 2007 and 2018, she sketched the handsome inventor on stage, welcoming an audience to a demonstration of his latest invention. Cut to the spectators. Instead of the respectable-looking men we might expect, there are rows of women panting like teenagers at a Harry Styles concert. As Tesla attempts to calm the crowd, his new contraption starts to sputter. ‘Sir, if I may,’ a voice interrupts from outside frame, ‘it looks like someone has thrown a pair of bloomers into the machine.’ Beaton shows us the frilly underpants then cuts again to the frenzied women. ‘Tesla!!!’ they shriek.

The black-and-white, six-panel vignette is characteristic of the Hark! series, which lampoons subjects drawn mostly from revolutionary history and canonical literature. Beaton’s lines are fluid and loose, her faces expressive. The humour is silly and unexpected, often leaning on the collision of the bygone and the contemporary. In ‘Sick Manuscript Bro’, a calligraphist monk in tonsure and robe invites another to ‘check out’ his Gospel of Mark fan fiction. In ‘Schedule Making’, a spoof on the opening scene of Macbeth (‘When shall we three meet again?’), one of the Weird Sisters protests that she’s busy that day – she has a dentist’s appointment – then whips out a spiral-bound calendar. Only occasionally does Beaton slip into easy parody, as in ‘Suffragettes in the City’, where Susan B. Anthony grows frustrated as her fellow campaigners swoon over men and get distracted by shoes. ‘Tesla: The Celibate Scientist’, from 2007, was the first of her comics to go viral. Two Hark! collections were later published, in 2011 and 2015, and stayed on the New York Times bestseller list for months.

Beaton started drawing the Hark! comics when she was 22 years old. She was working and living at a mining operation in the Athabasca oil sands in Alberta, Canada. She made comics in her bunk in the evenings, on paper lifted from the office printer, then scanned them in her lunch hour. Sharing her cartoons online offered a connection to the outside world in a remote, often dreary place. Beaton has now chronicled this period of her life in Ducks, an illustrated memoir – her first book-length work for adults. The occasional scene nods to Beaton’s artistic pursuits – including one in which the Tesla comic makes an appearance, so small it’s easy to miss – but these aren’t the focus. Instead, we follow her between 2005 and 2008 at three different mining operations (Syncrude, Opti-Nexen and Shell) with a year off along the way. The tone is serious, emptied of the irony that characterised the Hark! strips. Beaton’s drawing style has also changed: the lines, still fluid, are clean and controlled, the figures more proportional than their Goreyesque predecessors. The palette is mostly grey, the backgrounds washed with a bluish undertone.

Ducks opens in 2005. ‘This is me at 21,’ Beaton writes in a series of introductory panels. ‘I’m much older now, and three dimensional.’ This is the only section of the book to use the first person; the rest is told through dialogue and illustrations. Beaton calls her avatar ‘Katie’ and refuses us access to her thoughts. If conventional memoir offers the illusion that the ‘I’ of the narrator and the author are the same, Beaton seems to want to emphasise their difference.

When the book begins, Katie has recently graduated from university with an arts degree and is living with her parents on Cape Breton, a small, remote island in Nova Scotia, in a tight-knit community so dedicated to preserving its Gaelic traditions that it’s sometimes described as ‘more Scottish than Scotland’. Katie hasn’t decided what career she wants. Should she go to graduate school? Find a job at a museum? ‘Some of my friends are taking unpaid internships,’ she tells her younger sister. But she has student loans to repay and her parents don’t have the money to help her. The debt she has acquired is a ‘foot on my neck’.

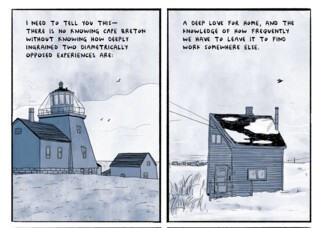

One early panel shows Katie in repose, a record player, assorted album sleeves and books stacked and scattered around her. You can make out a few of the titles: The Sounds of Cape Breton, The Folklore of Nova Scotia, Mabou Pioneers. She’s holding a copy of No Great Mischief by the Cape Breton writer Alistair MacLeod, whose narrator is haunted by his past and those of his ancestors. Beaton wants us to appreciate something fundamental about the place where she was raised: the people who grow up there share a ‘deep love’ for the island, but also know they will probably have to leave it. There’s no work – the steel, coal and fishing industries have died out. ‘This push and pull defines us,’ she writes. ‘It’s all over our music, our literature, our art and our understanding of our place in the world.’

In 2005, with oil prices on the rise, everyone is going to northern Alberta in search of ‘the good money, the better life’. Vast reserves of a tarry bitumen under the boreal forest have made the province Canada’s largest producer of crude oil. Stories about the oil sands tend to fall into one of two categories. Either they emphasise economic prosperity, describing the well-paid jobs and the money flowing into impoverished areas, or they focus on environmental catastrophe: forests razed by vast strip mines, tailings ponds filled with toxic sludge, polluted waterways and, in the surrounding communities, elevated rates of cancer and disease. Ducks can’t be slotted neatly into either. It’s a bit like the corpus of folk songs and tales from Cape Breton: a collection of small stories and anecdotes about working people, each made more meaningful by its proximity to others.

Katie’s first post is as an attendant in the tool crib at Syncrude, then the largest mining project in the oil sands. It’s one of the few roles that don’t require a trade, and in her job interview she claims she’s familiar with tools because her father owns a hardware store (he’s actually a butcher). She moves to a town called Fort McMurray, just south of the mine. Driving through it for the first time she sees a Baptist church and an Islamic centre, a casino and a handful of clubs, a lifted truck and a restaurant catering to Newfoundlanders. It is, in other words, a town marked by the industry that supports it. (Somalis and Canadians from Newfoundland are among the largest groups of migrants to the oil sands.) We already have a sense of Beaton’s deft use of scale and pacing, the way she adjusts the size and orientation of her panels and the width of her gutters. When Katie rides the bus to work for the first time, she spots the mine in the distance and we see her view from the window on the adjoining page. The image stretches right to the edge of the page, the mine’s built structures – roughly sketched black vertical lines with white dots for the lights – running in a band through the centre. Enormous grey plumes of smoke hover above. It’s not yet dawn, and much of the page is a viscous black, which also gives the impression of oil seeping through.

The hours are long and erratic. Katie works twelve hours a day, six days on and six days off, alternating between day and night shifts. Winters are harsh, with little sunlight and temperatures below -40°C. The air is contaminated: early on she develops a cough, and itchy welts surface on her back. The training videos stress safety, but all the companies skimp on basics such as protective vests. Most of the labourers have travelled from elsewhere, leaving behind their families. This is their second or third career. ‘I’m still a fisherman,’ a mechanic foreman from Newfoundland tells her. ‘I’m just here.’ Everyone is lonely and homesick: set pieces showing Katie using a dial-up internet connection and buying her first mobile remind us that this is a time before smartphones. The isolation is most extreme in the camps, where workers live in temporary accommodation provided by the oil companies. ‘The camps are the shadow population,’ a taxi driver warns her. ‘They live here, but they don’t live here. Do you know how people treat a place where they don’t live?’

In a place where men can outnumber women by fifty to one, casual misogyny and harassment are rife. The men call Katie ‘cutie’ and ‘doll face’, gossip about other women workers (‘Lot of guys been with her, you know’) and ask inappropriate questions: ‘You here on nights, you ever take anyone out back? For a little – you know …’ Small changes in the placement or angle of an eyebrow capture Katie’s discomfort. Narrowed panels and cropped frames convey her sense of being trapped. Things get worse when Katie takes a job at Opti-Nexen. Male colleagues sometimes open the door to her bedroom: ‘Oops! Wrong room,’ they say, feigning confusion. When she is temporarily assigned to a new workstation, men line up around the building to ‘get a look’ at her and compare notes on her appearance. ‘Got a tight arse like the one who does my room,’ one of them says.

Katie soon discovers what happens to women who stand up for themselves. When she tells a manager that she doesn’t like to be ogled, he replies: ‘You knew this was a man’s world when you came. You’re going to have to get a thicker skin.’ Humiliated, she apologises. Being dismissed is demoralising, but being listened to can be worse. W0men whose complaints are taken seriously find they are shunned by their peers and often leave. ‘Women have gotten guys fired just for pissing them off,’ one colleague says. ‘Fuckin’ crazy girl, probably making everyone miserable wherever she fucked off to,’ another says of a woman who filed a complaint. When Katie is raped – twice, at parties – she tries to go on as if nothing happened. The panels illustrating her flashbacks, like those of the assaults, are tinted sepia. Even after her older sister, Becky, arrives with a friend (they, too, have loans to pay off), Katie avoids saying anything until Becky forces her confession.

By this time, she has decided to leave the oil sands. She moves to Victoria, British Columbia for a part-time job in a small museum. In the local library she comes across a collection of folk tales by the Nova Scotian folklorist Helen Creighton. ‘Did you know she took out all the bawdy stories from her collections because she didn’t think they were fit to print?’ Katie says to a colleague. ‘Makes you wonder what was left out though, doesn’t it?’ Leaving out the violence of the oil sands would be a misrepresentation – even if, as Beaton writes in her afterword, putting it in leaves her ‘wary of the sensationalisation of my narrative’. She isn’t out to indict the men she worked with. In fact, she’s not convinced that the way people behave in the oil sands says much about the way they really are. At one point, Katie confides to a friend that the worst part of being harassed is that the people ‘sound like me, in the accent that I dropped when I went to university … they look like my cousins and uncles, you know, even though they’re from all over the country … this place creates that where it didn’t exist before.’ Most of the men never bother Katie, and a number of them are kind to her. There’s the guy from ‘down home’ who brings her a tin of homemade cookies on Christmas Eve; the mechanic who presents her with two photographs he’s taken of the Albertan sky, one lit up by the Northern Lights, the other by a rainbow; the equipment co-ordinator who, eager to cheer her up, takes her for a meal at the place ‘where the big shots get their lunch’.

Katie likes working at the museum but doesn’t earn enough, even with the extra cleaning job she takes on. In the book’s final section, she returns to Alberta to work as an administrator in the warehouse office at Shell. Here Beaton focuses on the destructive effects of the oil sands. A contractor is crushed by one of the heavy transporters. A man is fired after defecating in the parking lot, a sign he’s been using cocaine. The warehouse foreman shows signs of increasing distress, until one day he disappears. It isn’t easy to ask for help in a place like this, and there isn’t much on offer. ‘I don’t know how many safety meetings I’ve been to here,’ Katie says, ‘but I’ve never been to one about drugs. Or alcohol. Or why there’s so much of both here.’ There are physical ailments, too, not all of them understood or even recognised. (In the afterword, we learn that Becky died of cancer. ‘She was working there until she got diagnosed,’ Beaton said in an interview. ‘And of course you have to wonder, right?’)

The dangers of the oil sands aren’t confined to the people working in them. Katie arrived at the mines knowing little about the Indigenous communities living nearby or the long history of violence against them. A YouTube video featuring Celina Harpe, an elder from the Cree community of Fort McKay, is therefore something of a revelation. ‘First Nation people’s lives pay for the oil they take out of the land here,’ Harpe says in a series of panels re-creating the video. ‘They spoil and ruin our water, the air, pretty much everything else … Their almighty dollar comes first. That’s pretty sad. You can’t eat money.’ ‘This is us too,’ Katie tells a colleague. ‘We’re not the president of Shell, but we’re here.’

The ‘ducks’ of the book’s title make their first appearance in a panel depicting the New York Times website. The first two paragraphs of a story are visible, recreated in type just large enough to read. They report that hundreds of migrating ducks have died after landing in a toxic tailings pond at Syncrude. The mine authorities failed to set up the noisemakers designed to frighten them away. The article is the focus of the safety meeting Katie attends that afternoon. ‘We don’t want that happening here,’ someone says, meaning the PR disaster as much as the loss of life. Only at the end of the meeting does someone mention a crane operator at their own mine, who had a heart attack and died on the job.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.