Every hour I make scissor movements, bicycles, or stick my feet against the wall. To quicken it. When I do, a strange heat spreads like a flower somewhere at the base of my stomach. Purplish blue, rotten. Not painful, just before pain, an unfurling on all sides that hits against my hips and dies at the top of my thighs. Almost pleasure.

Denise Lesur is in her student room, trying to bring on her abortion. She’s come back from her backstreet appointment ‘skewered’ by a probe, ‘a red serpent’, threaded through her cervix to set off uterine contractions, and now she has to wait. We are on the first page of Annie Ernaux’s first novel, Les Armoires vides, and we are going to have to wait with her. In pregnancy, quickening refers to the first movements of the foetus in the womb, but here we are waiting for a death, and as we turn the pages of the novel and get closer to the end we are quickening it too. If we stop reading, the death won’t happen. We hold the fate of the foetus in our hands.

The novel is an account of how Denise got here, with her legs up against the wall, but Ernaux gives us not so much a narrative as a narrative atmosphere. There is no plot, or not one powered in any straightforward sense by the abortion (there are boys and there is some sex, but there is no narrative time spent on realising you are pregnant, or trying to access medical care). Denise’s abortion is the catalyst for her recognition that she’s in the wrong plot. She’s been living inside someone else’s story. She has misidentified what’s real.

Denise is a scholarship girl, and there’s a lot in the novel about the gulf between the café-bar where she lives with her parents – the drunk men pissing in the garden and sizing her up, the coarse women trading stories about sex and who’s gone and got themselves in trouble – and the proper, discriminating, world of the convent school and the university. Home is where there are no distinctions, where people ‘dive in’ to whatever is offered: food, drink and, however clandestinely, sex. They hoover up everything, gorge on it, Denise included – she is all appetite, desire, fat-bellied greed. And now her belly has caught up with her. She vomits up her foetus as she vomits up her past. ‘The probe, the belly, it’s never really changed, it’s always been in bad taste, the Lesur girl come back.’

Les Armoires vides was published in 1974, which is late for the scholarship pupil plot in Britain and Ireland. John McGahern, Edna O’Brien, Richard Hoggart, Raymond Williams: they were all born between the end of the First World War and the early 1930s, and published their stories of class alienation in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It’s a bit late, too, for the middle-class unmarried motherhood plot: Lynne Reid Banks, The L-Shaped Room (1960); Margaret Drabble, The Millstone (1965). That phrase, ‘bad taste’ (‘mauvais goût’), gives us a clue to what Ernaux has been reading. Pierre Bourdieu’s Les Héritiers: les étudiants et la culture (The Inheritors: French Students and Their Relation to Culture), written with Jean-Claude Passeron, was published in 1964. It was here he first tried out his argument that educational inequality has cultural as much as economic causes; that the French education system bolsters rather than alleviates disparities; that we are bound by our social origins to what he calls aesthetic dispositions and have little power to choose otherwise.

Denise is a perfect example of Bourdieu’s thesis. As she grows up, she becomes alienated from what Ernaux calls ‘the real’. Or rather, the real of her childhood disappears under the onslaught of the real of school, for which she has to learn a whole new language. ‘I understood more or less everything that the teacher was saying, but I wouldn’t have known how to find the words by myself.’ Her account switches between her newly acquired school diction and Normandy slang, an idiom that ‘lives in the mouth’ and is especially useful for talking about food and sex. But the two languages aren’t just home and school, spoken and written; they designate two entirely different ways of dividing the relationship between genders, and between what is kept private and what is allowed to appear in public. Denise wishes she could take her parents out ‘into the real world’ inhabited by her middle-class schoolfriends, but she knows she can’t because they wouldn’t have a clue how to behave, and their language proves it. All those words for bum and fanny and dick she knows because there is no distinction between the private world of the family and the world outside – after all, the Lesur family home is a public bar. When she reads Balzac’s Père Goriot she learns that proper families have separate spaces. Even the depressingly down-at-heel boarding house, the Maison Vauquer, maintains a separate dining room, and she knows that what she reads in Père Goriot is true because ‘authors didn’t exist. All they did was transcribe the life of real people.’

The only possible attitude to home after having learned about real life in literature class is one of ironic detachment, a trick she also learns from novels. But the abortion changes all that, as Denise realises that books are not her friends but her nemesis. What she is experiencing, legs in the air, is definitely real – she can feel it. But there is no novel that describes what’s happening to her, and this isn’t accidental or an omission. It is the cruel point of her experience – that it can’t exist, or doesn’t count, in the world of the convent school and the university classroom, the edifice of educational propriety that has gifted her literature and on which she has been planning her future.

There’s nothing in there for me about what’s happening to me now. Not one passage that describes what I am feeling now, to help me to get through these dirty moments. One can easily find a prayer for any occasion, births, marriages, death’s door. You should be able to find an extract on anything, on the 20-year-old girl who has gone to the maker of angels, who comes out again, what she thinks as she walks along, and as she throws herself down on her bed. I would read it again and again. Books are silent on this topic.

Why might that be a big deal? Why should it matter that books have been silent on abortion? And in what way have they been silent? What is it about realist plots that renders the reality of women’s sexual lives invisible? Denise isn’t looking for references to abortion in novels – she wants a how-to guide. How to access it, how to undergo it, how to think about it. Literature is where she goes to learn how to behave. But abortion doesn’t even function as a plot device in the 19th-century novels she reads, where the trials and tribulations tidied up by the marriage plot are problems like the death of your father or the loss of your fortune. (Except when the woman dies: Hélène’s abortion in War and Peace is both not really there – it’s implied rather than stated – and central to the plot because she dies as a result, leaving the way clear for Pierre to marry Natasha. It’s a marriage plot, not an abortion plot.)

Ernaux wrote Les Armoires vides in 1973, the year of Roe v. Wade, and two years before abortion was legalised in France. (It’s worth remembering that Roe’s argument in favour of a constitutional right to abortion was based on the right to privacy protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, to the dismay of activists and scholars who argued that it should have been based on the right to equal protection before the law.) She has described writing the novel as a way of taking part in activist politics: simply by writing about an experience that was mired in illegality and shame she was making a claim on public discourse. She was active in the campaign group Choisir – but it seems to me ironic that she was standing up for a woman’s right to choose, because everything about Les Armoires vides suggests that Denise can’t and doesn’t make choices. Her life is determined by her milieu. ‘I can’t separate what I do wrong from my background,’ she says, and what she’s pointing out is that, of course, she’s going to have to have – in effect, to be – an abortion, because she doesn’t have a separate dining room. She’s always been gorging and vomiting. There is no division between the public and private in her world, and therefore no self to do the choosing with. There is no possibility for her of making the choice to be the kind of woman who isn’t from the wrong side, who won’t be the kind of woman who inevitably gets pregnant and has an abortion. She’s been ‘fucked from all sides’, as she puts it, betrayed by what Bourdieu would call her ‘disposition’.

Nearly thirty years after Les Armoires vides, Ernaux returned to the story of her abortion in L’Événement, which was adapted by Audrey Diwan into the film Happening, released last year. Ernaux put abortion in literature, if not exactly in the novel: Happening repeats the staging of working-class abjection but this time as memoir, which lends a rather different valence to Ernaux’s favourite term, ‘the real’.

Is it really Balzac’s fault that we have a world in which working-class girls have to get illegal abortions? I think Ernaux would say it is, and I am inclined to agree with her – or at least to posit that Balzac and his gang are not innocent. The novel form, as it developed in England and France in the 18th and 19th centuries, helped define gender differences, mapping them onto the division between public and private spheres, politics and the family. It was the place where a woman’s humanity as a thinking, feeling being was established, where moral values were attached to qualities of mind, where maternity – as opposed to reproduction – was designated part of female nature.

I’m certainly not the first to suggest that the history of the novel can’t be understood separately from the history of sexuality, by which I mean the cultural dimensions of sex, including gender. I am not arguing that we are still dominated by the public/private distinctions of 18th and 19th-century polite society. Yet the ideas of female nature and female desire honed in realist fiction helped produce readers who understood themselves in the psychological terms that shaped that fiction. It wasn’t simply a benign feedback loop. As the heterosexual-horror plot in Elif Batuman’s recent novel Either/Or makes plain, novels got us all misidentifying the real.

What might it mean for the way we think about abortion if we take seriously the problem of what fictional narrative – novels and stories and films – says about it, or doesn’t say, what it makes impossible to say? Can we tell stories about abortion that don’t get snagged on gendered assumptions about human nature and moral feeling, that think in different psychological terms, or not in psychological terms at all?

Another way of positing this set of questions is to ask how modern abortion came to seem intuitively a moral issue. The US Supreme Court ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson, which overturned Roe v. Wade, is insistent that abortion is a ‘critical moral question’, a ‘profound moral question’, a ‘fundamental moral question’. The Dobbs ruling focused on Mississippi’s Gestational Age Act, which banned abortions after fifteen weeks. The Mississippi Department of Health wanted to set the legal barrier for access to abortion below the stage of foetal viability (when the foetus can survive outside the uterus). But the Dobbs court went much further, and rejected viability as a legal concept, overturning both Roe and the 1992 Supreme Court decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which had upheld viability as a reasonable boundary line and compromise between the rights of the pregnant woman and the rights of the foetus. Dobbs argued that the Roe court had ‘usurped the power to address a question of profound moral and social importance that the constitution unequivocally leaves for the people’. I certainly don’t mean to deny that moral and ethical questions surround the practice of abortion. But what exactly are they, and when did they take shape?

Abortion stories, as a genre, haven’t been terribly interested in questions of morality. Before legalisation in the 1960s and 1970s, abortion stories subordinated profound moral questions over the personhood, or potential personhood, of the foetus to the problem of access. Ernaux’s protagonist, in both the 1974 novel and the 2000 memoir, never once considers the morality of her action – her problem is the law, not ethics, and the fact that her desire not to have a child in 1963 has put her on the wrong side of it. Or here’s Vivian Gornick and her eighty-something mother sharing stories of their abortions, in the 1930s and the 1960s, after a lifetime of silence:

From out of nowhere she says to me, ‘So tell me about your abortion.’ She knows I had an abortion when I was thirty, but she has never referred to it. I, in turn, know that she had three abortions during the Depression, but I never mention them, either. Now, suddenly … ‘I had an abortion with my legs up against the wall in an apartment on West Eighty-Eighth Street, with Demerol injected into my veins by a doctor whose consulting room was the corner of Fifty-Eighth Street and Tenth Avenue.’ She nods at me as I speak, as though these details are familiar, even expected. Then she says, ‘I had mine in the basement of a Greenwich Village nightclub, for ten dollars, with a doctor who half the time when you woke up you were holding his penis in your hand.’ I look at her in admiration. She has matched me clause for clause, and raised the ante with each one. We both burst out laughing at the same moment.

The stories are about how, not why, and definitely not whether. They are grubby stories of female abjection at the hands of the law, and both women have mastered the hyper-realist style and satirical tone which enables them to express that abjection while holding shame at bay. They know the script, clause for clause, and questions of autonomy and personhood aren’t part of it. But the years of silence are. Gornick makes Ernaux’s point: generations of women are not speaking about their abortions, so that everyone has to work out for themselves how to do it, and how to think about it. This isn’t the silence of moral guilt but personal shame – that they have been caught in this predicament and holding some dick’s penis is, more or less literally, the only way out.

In illegal abortion plots it’s usually the men who have to face the moral consequences of unplanned pregnancies – Arthur Seaton, for instance, in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning or Michael Caine’s Alfie – while the women suffer, from their men as much as their abortions. The moral question faced by these men, who until now have been indiscriminately handing round their penises, is whether they will take responsibility for the sex that has caused the foetus, not responsibility for the life of the foetus itself. They do this by finding the money for the abortion and sometimes by being there in person.

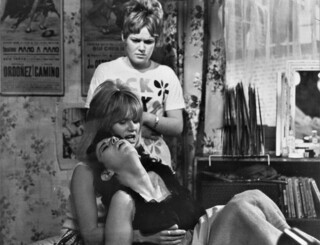

Or they don’t take responsibility – take, for example, Rube’s abortion in Ken Loach’s BBC adaptation of Nell Dunn’s book Up the Junction, which helped bring about the 1967 Abortion Act. This is a case in which it mattered a lot how the abortion story was told. Loach avoided straight realism, mixing in documentary techniques, including a voiceover interview with a GP during the abortion scene. We watch Rube walking across a common after the procedure (her version of cycling her legs in the air), then sweating and screaming in pain; the panic of those around her; the phone call for help. When her body quietens, we know that the foetus has been expelled. We imagine it lying somewhere just out of shot. And at the same time, we listen to the matter-of-fact voice of the doctor explaining that in his surgery he sees a woman every week looking for an abortion, that 35 women die every year of botched abortions, and that’s not counting the many women who are unable to conceive afterwards (the plot of Graham Swift’s Waterland). Viewers – and there were ten million of them – were forced to see Up the Junction’s storyline as a public health matter, and it became part of a political campaign. But it was also personal. Behind the statistic of 35 deaths a year was the mother of Tony Garnett, Up the Junction’s story editor. She had died of septicaemia following a backstreet abortion in the early 1940s, when Tony was five years old. Nineteen days later his father committed suicide.

One of the consequences of the legalisation of abortion (I take for granted the saving of women’s – and indeed men’s – lives) was a shift of the moral burden, in stories but in real life too, from men to women. ‘Take care of yourself,’ Imani’s husband, Clarence, says as he puts her on a plane to New York in Alice Walker’s story ‘The Abortion’. ‘Yes, she thought. I see that is what I have to do.’ She has the procedure, alone, in an ‘assembly line’ clinic. And the marriage unravels from that moment.

This isn’t Imani’s first abortion. Walker’s story, written in the 1970s, compares her post-Roe procedure (‘an abortion law now made it possible to make an appointment at a clinic, and for 75 dollars a safe, quick, painless abortion was yours’) to a pre-Roe abortion in college, carried out in an Italian doctor’s apartment – maybe the same one visited by Vivian Gornick. (‘When you leave,’ the doctor’s wife tells her, ‘be sure to walk as if nothing is wrong.’) This first abortion,

she frequently remembered as wonderful, bearing as it had all the marks of a supreme coming of age and a seizing of the direction of her own life, as well as a comprehension of existence that never left her: that life – what one saw about one and called Life – was not a façade. There was nothing behind it which used ‘Life’ as its manifestation. Life was itself. Period. At the time, and afterwards, and even now, this seemed a marvellous thing to know.

Walker is surely alluding here, with her capital L, to Lennart Nilsson’s famous image of a foetus on a 1965 cover of Life magazine. It’s a startling claim, figuring abortion as the pro-Life choice. There’s nothing behind Life, nothing we can’t see and know.

But it’s the second abortion in Walker’s story that is the more radical. Imani is married with a child and has no compelling ‘reason’ not to have another baby: ‘If she had wanted the baby more than she did not want it, she would not have planned to abort it.’ The story is, I think, in dialogue with the black revolutionaries of the 1960s and 1970s who rejected the pill, and later abortion, as a form of genocide against the black population – not such a crazy idea, as Angela Davis explained in Women, Race and Class, when you think about the entwined roots of birth control and eugenics and the fact that young black women were still at that time subject to forced sterilisation. For many people, the question was not and is not ‘Am I allowed to have an abortion’ but ‘Am I allowed to have a child?’ Walker acknowledges this by setting Imani’s abortion alongside a memorial service for a young black girl killed on her way home from her high school graduation: Imani thinks of these attacks on black life by white law enforcers as ‘extreme abortion’. There is a genocide, she’s saying, yet she goes ahead with her own abortion and she makes it explicit that she does so because she wants to. She offers no other justification.

The same is true of Up the Junction. We know that Rube isn’t married and that she’s only seventeen, but Dunn, Loach and Garnett explicitly refuse to offer justifications for the abortion. At one point, Rube tries to explain why she wants to end the pregnancy but Winny, the kindly-faced family friend who will carry out the abortion (played by Ann Lancaster, better known as a comic actor), cuts her off: ‘Oh, there’s no need to explain. How can you ever explain anything? It’s the most bloody difficult thing in the world.’

There’s no need to explain, no need for a story – certainly not one about feelings and motivations. If Rube ever talks about her abortion to a future daughter she will tell the kind of story Gornick and her mother tell – a hard-edged, world-weary story of physical abjection. These are stories about bodies, not feelings, and that is one of the reasons they don’t fit the realist novel’s dining room scenario.

It was only after legalisation that storytelling became bound up with abortion’s moral economy. Once power over life was delegated to individuals – women especially – making physiologically and psychologically healthy choices became a new kind of obligation. A woman wanting an abortion has to be able to provide a legible narrative, to tell a good story. In the UK, abortion is still prohibited under the 1861 Offences against the Person Act; what the 1967 Abortion Act allows is a legal defence for doctors who perform abortions that fit a set of criteria including serious foetal abnormality and the risk of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman. The reason given for around 98 per cent of all abortions is the risk to the woman’s mental health. You have to have a story, and even if that story is attenuated to almost nothing (I’m too young; I haven’t a partner; I can’t afford it) what’s important is that you must be seen to decide. In order to remain a woman while having an abortion (unlike Denise Lesur, who is just a belly) you have to perform the act of self-reflexive decision-making. There is little room in this genre for expressions of ambivalence, regret or disappointment. No space for rage and self-laceration (the realisation that you are married to the wrong bloke, that your boyfriend’s a shit, that your life is chaotic, that you misunderstood your own wants). No space for the desire for the destiny of this child to have been different that may be present even in necessary abortions. And what if you aren’t a good storyteller? As a late-term abortion provider in the US documentary film After Tiller (2013) asks, ‘Why would it be OK for me to say, “No, you’ve got to tell me a better story than that”?’

The notion of responsible choice was the target of Alexander Payne’s 1996 satire Citizen Ruth, starring Laura Dern as a homeless drug addict who has already had four children taken away from her by social services. It’s a film about a woman’s right to make poor choices. Caught between the opposing sides in the abortion debate, styled as a battle between evangelical family-value warriors and lesbians who worship the moon, she refuses to make a decision based on anything except how much money she’ll get. She decides according to a literal rather than moral economy. Ruth is an extreme example of the many women who can’t articulate reasons, who don’t have them, who don’t have ‘good’ reasons, or don’t understand them. Think of the teenager, 17-year-old Autumn, at the centre of the abortion road movie Never Rarely Sometimes Always (2020), who is all but mute throughout the film. She is pressured into watching a pro-life film at the anti-abortion facility that masquerades as a women’s health clinic in her home town in Pennsylvania, and does so in silence. It makes no difference to her wish for an abortion, but she doesn’t bother saying so. Silence in the face of the moral case being put to her is part of the texture of the abortion story. Silence is the way she says no. Ernaux implies that novels are silent on the topic of abortion because nothing can be said about it in the terms afforded by novels. And this film suggests that silence is the only strategy in real life too. Autumn’s story, of sexual harassment and physical abuse, is one she barely understands. And it is never going to balance the scales against the abstract moral arguments of the pro-lifers.

The problem for those who take an absolutist moral stance on abortion is that most people don’t agree with them. In the US, 62 per cent say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 36 per cent believe it should be illegal in all or most cases. But there are relatively few purists. Even people who say it should be legal are generally in favour of some restrictions, and people who are opposed think there are some cases in which it should be allowed (36 per cent of opponents of abortion think it should be legal in cases of rape). One in three adults thinks both that human life begins at conception and that the decision to have an abortion belongs solely to the pregnant person. Just over 14 in 1000 women between 15 and 44 had an abortion in the US in 2020 (Guttmacher Institute); that’s more than 900,000 women each year. The age-adjusted abortion rate is higher in the UK, where in 2021 it was over 18 in 1000 – nearly 215,000 abortions.

Pro-life foetal imaging – there are legal requirements in some states that women planning on abortion have to see ultrasound images of their foetuses before they can be allowed to continue – is a response to the fact that even if people feel there are profound moral questions hanging over abortion, many of them feel those questions are complex, with ethical demands on both sides. Forcing the viewing of such images is a way of trying to get people to acknowledge the foetus as a subject, a person making a claim. But it is not a very effective anti-abortion strategy. Research carried out by the Embryo Project found that 98.4 per cent of women went ahead with their abortions after seeing ultrasound images, compared to 99 per cent without, and it made no difference at all to early abortions. It seems to me significant that representations of foetal life have so little effect on women who are carrying an unwanted pregnancy. Anti-abortion advocates think it is significant too, which is the reason they have had to resort to banning terminations or making them hard to access.

For hundreds of years , before the law clamped down, women’s abortions were governed by a different framework. This is not my contention, but one of the central holdings of the judgment in Roe v. Wade: for centuries, common law held that, at least before quickening, abortion was a lesser crime, and perhaps not really a crime at all. Roe also argued that it was ‘doubtful … abortion was ever firmly established as a common-law crime even with respect to the destruction of a quick foetus’. It was difficult, it was dangerous, it was something to be kept private, but it was practised and known to be practised, without moral uproar. It is that claim that has been rejected by the court in Dobbs v. Jackson.

I am not a constitutional lawyer, nor am I a scholar of American democracy. But there are plenty of legal experts and even three or four – let’s call it three and a half – Supreme Court justices who disagree profoundly with the interpretation of American law that the Dobbs majority opinion put forward. And anyway, it turns out that the principal grounds of disagreement between Roe and Dobbs turn on an interpretation of American history, rather than American law, and in particular what was in the minds of the drafters of the Fourteenth Amendment. It’s all about 1868, which until recently I thought of as the year when Louisa May Alcott published Little Women.

Dobbs insists that the only liberties protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment are those ‘deeply rooted in this nation’s history or tradition’. Abortion wasn’t considered a right when the clause was ratified in 1868, ergo, it can’t be a constitutional right now.

Guided by the history and tradition that map the essential components of the nation’s concept of ordered liberty, the court finds the Fourteenth Amendment clearly does not protect the right to an abortion. Until the latter part of the 20th century, there was no support in American law for a constitutional right to obtain an abortion. No state constitutional provision had recognised such a right. Until a few years before Roe, no federal or state court had recognised such a right. Nor had any scholarly treatise. Indeed, abortion had long been a crime in every single state. At common law, abortion was criminal in at least some stages of pregnancy and was regarded as unlawful and could have very serious consequences at all stages.

Roe, according to the Dobbs majority, ‘either ignored or misstated this history’. Their argument is almost entirely based on the work of one scholar, Joseph Dellapenna, a retired expert on international water rights who published a partisan book on abortion law in 2006. Until recently this book was not easy to get hold of. There were only four hundred copies in libraries around the world, and it had not become part of the historiographical debate on abortion (since the Dobbs ruling it has been reissued). It was ignored by historians for good reason, but Dobbs relies almost exclusively for its historical claims on this tendentious book, alongside the amicus brief prepared by Dellapenna in support of the Mississippi Department of Health.

Dellapenna maintains not only that ‘abortion was a common law crime from the earliest recorded days’, but that ‘the common law was followed and codified in the states and territories in order to protect the life of the unborn child.’ He rejects the idea that historical research might require unearthing what he ridicules as ‘the “lost voices” of mute classes who, by definition, find no or scant evidence in the historical record’. He insists that ‘the public attitudes of formal, legal institutions’ represent ‘the true values of society’ and implies that for that reason there is no need to look beyond legal documents and legal traditions. The Dobbs ruling cleaves to ‘the great common law authorities’ with no concern for whether or in what way common laws were enforced, how often they were prosecuted, what juries thought, what kinds of sentence were handed down. Dellapenna argues that ‘judgments of not guilty rather than dismissal prove that the indictments and appeals were valid under the common law,’ and ignores the wealth of historical evidence that suggests juries were reluctant to convict on charges of abortion, even after quickening, because they felt sympathy for the women involved. It might technically be a crime, but it wasn’t a crime that should be prosecuted.

The Dobbs court didn’t want to think about this, or about the social background against which laws prohibiting abortion were passed in the mid-19th century, or about the relationship between the judiciary and the people. There is no contextualisation of legal history, no weighing up of evidence, and random and selective quotation. Dellapenna claims that abortion prosecutions were rare because the practice itself was rare, maintaining that until the late 19th century it was ‘tantamount to suicide’ – and it is true that infanticide and abandonment were more common means of getting rid of unwanted children than abortion, and almost as likely to be condoned by juries.

But this introduces a logical aporia. If abortion was so rare, why so many laws to deal with it? Why so many campaigns in favour of legalisation? Even his own sources suggest that the practice was widespread, and often condoned. In 1923, for example, the Wisconsin Supreme Court argued that there was no point getting rid of the quickening distinction when it came to abortion because to the mass of ordinary people an early-term abortion was not morally wrong:

In a strictly scientific and physiological sense there is life in an embryo from the time of conception, and in such sense there is also life in the male and female elements that unite to form the embryo. But law for obvious reasons cannot in its classifications follow the latest or ultimate declarations of science. It must for purposes of practical efficiency proceed upon more everyday and popular conceptions, especially as to definitions of crimes that are malum in se. These must be of such a nature that the ordinary normal adult knows it is morally wrong to commit them. That it should be less of an offence to destroy an embryo in a stage where human life in its common acceptance has not yet begun than to destroy a quick child is a conclusion that commends itself to most men.

The ordinary normal adult in Wisconsin had apparently not been convinced that early-term abortion was really a crime, more than fifty years after the majority of states had passed laws criminalising it – those laws that form the heart of the Dobbs court’s claim that by 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was passed, it was clear to everyone that even a pre-quickening abortion was a crime against the unborn child. In his 1910 treatise, The Prevention and Treatment of Abortion, Frederick Taussig, a gynaecologist and professor of obstetrics at Washington University, described abortion as ‘the one crime that is almost universal, is found among all classes, in all countries’:

Our daily press advertises with impunity, under the thinnest sort of veil, medicines that will ‘regulate’ the flow and physicians or midwives who will help those ‘in trouble’. It is a crime that is punishable by a severe penalty, but is practically never punished. Is it surprising, then, that we find an estimate of eighty thousand criminal abortions a year in New York, six to ten thousand a year in Chicago, and like numbers elsewhere?

At this point Taussig was against it. But by 1936, when he published his second book on abortion, he had changed his mind, arguing that women needed to be helped to legal abortions rather than punished for illegal ones, because they were having them anyway: ‘Every physician will testify that it is without any feeling of guilt that most women speak of induced abortions in the consultation room.’

I’ve only quoted from sources that Dellapenna also references. You could find plenty of other evidence about the ‘lost voices’ of mute classes, who mostly thought, and think, about abortion in practical and physical and personal rather than moral terms. And plenty of social historians have found it. But pointing out the errors in the Dobbs ruling’s understanding of social history is clearly futile. A more accurate understanding of the past isn’t what Alito et al. are interested in. The argument between pro-life and pro-choice defenders is not really, or not only, about the rights and wrongs of abortion. It’s not going to be solved by coming to a shared conclusion about the moment when life begins, or even a conclusion about what people thought about the moment when life begins in 1868. The abortion debate is a means of leveraging broader struggles, over the family, gender, citizenship and the idea of the nation. Indeed, the majority in Dobbs make this explicit when they claim that their decision ‘is not based on any view about when a state should regard pre-natal life as having rights or legally cognisable interests’, but on their interpretation of values ‘deeply rooted in this nation’s history and tradition’ and ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty’. It’s in their interests to choose the narrowest ground possible on which to argue for their version of American history.

Reading through the logic chopping and attenuated abstract reasoning of the Dobbs ruling I was reminded of an International Theological Commission document from 2007 which quietly buried the concept of limbo. Limbo had been unpopular among the faithful for a long time, so I was interested to learn why the Church had chosen this moment to do away with it. The document promised to explain ‘The Hope of Salvation for Infants who Die without Being Baptised’. The theologians acknowledge that limbo has been on the way out for a long time. It’s never been core doctrine. The new Catholic catechism, revamped in the 1990s, doesn’t mention it. But, the document explains, the question of what happens to unbaptised babies when they die is an urgent one. Because of ‘cultural relativism and religious pluralism’ many more babies than before are not baptised. And because of ‘in vitro fertilisation and abortion’ there are now millions of eternally trapped fertilised-egg and embryo souls, about which the Church also has to take a view. The theologians who drew up this paper don’t seem worried (or not unduly) about the distress of believing parents who are told their dead babies will float in limbo for all eternity, but about numbers: the limbo constituency is seriously large. It is as though limbo is an actual place, which is going to get very full very quickly unless we change the rules of admission. And these vast numbers of unbaptised embryos, as well as the dead babies of culturally relativist parents, have forced the issue.

‘The Hope of Salvation’ is a strange read. I had not properly appreciated that theologians are essentially lawyers, who have to come up with arguments for and against what happens after death based on a kind of case law (the gospels), and the various precedents and interpretations of the law that the Church fathers have laid down across the millennia. The problem of unbaptised infants, babies and now embryos, is a thorny one. Why would God turn these innocent souls away at the gates of heaven? It seems cosmically mean. On the other hand, if the salvation of human beings depends on the Holy Spirit, how could souls who haven’t been blessed with the sacrament not be excluded?

The debate about where the souls of unbaptised embryos may or may not go is patently bizarre. The rules of the game ensure that pretty much anything can be said. But it makes sense that papal theologians thought it necessary to clear up that messy area of, let’s call it common law doctrine, in which some babies didn’t count in quite the same way as other babies. It wasn’t until 1869, the year after the Fourteenth Amendment, that the Catholic Church decided it was morally safer to assume that ensoulment happens at conception rather than at quickening or, as Augustine maintained, forty days after conception for a male, and ninety days after conception for a female foetus. In other words, up until 1869, the Catholic Church agreed with the ordinary normal adults of Wisconsin, that embryos and foetuses were not persons with souls, destined for limbo, but a more ambivalent form of matter.

And is this more bizarre than the Georgia state law that offers full legal recognition to the foetus, including the right to claim a dependent tax break from six weeks’ gestation? Georgia’s personhood provision also means foetuses can be included in some population counts. Like limbo, Georgia must be getting quite full now, with all those six-week embryos vying for a place, though up to one in five of them will be lost to miscarriage and end up looking for somewhere else to go.

The point I’m making here is that ‘evidence’ – real testimony and realist storytelling – isn’t going to make any difference to this debate. Laurence Tribe, writing in the New York Review of Books last September, argued that Roe may have been bad constitutional law but it was good legislation, creating the compromise that we have to have and that most people wanted. For years feminists have been arguing that due process was the wrong way to argue for the right to abortion, and that the viability line was a hostage to fortune. But it was not a better understanding of the privacy argument or the Due Process Clause that made the Supreme Court realise its error. The Dobbs ruling is a matter of theocratic disposition not reasoned legal argument. The ruling’s dismissal of the equality argument for a right to abortion in a single sentence is proof, if proof were needed, that the justices and their backers weren’t interested in thinking through the law in a way that responds to the complexity of lived experience. By definition they weren’t interested in that. Hence the need to argue their case as narrowly as possible – via a tenuous thread of public legal statements made in the 19th century.

What kind of abortion genre would be legible to this disposition? Not psychological realism, not documentary accounts of crises in healthcare, not social media protest movements, such as Shout Your Abortion, which aims to undo abortion stigma by encouraging the hundreds and thousands of women who have had abortions to broadcast that fact. I am not suggesting we should stop telling stories about the human cost of banning abortion, and it’s clear those stories need to be accurate. The facts matter, such as that most abortions in the US are accessed by the poor and people of colour who already have children, and can’t support them, rather than single white women in relationship difficulties. Up the Junction’s fictional plot helped bring about the 1967 Abortion Act; the death of Savita Halappanavar, denied an abortion because the foetus, though unviable, still had a heartbeat, catalysed an abortion storytelling campaign in Ireland, filtered through journalism, social media and protest, which helped to quash the Eighth Amendment.

But these stories make no difference at all to people who worry about where embryos go after death. Their genres are mystical and eternal, touching the borders of speculative and science fiction. They are best captured not in narrative form but in the manipulated images of isolated foetuses floating in infinity, magical proofs of the doctrine of eternal life. What does abortion realism have to say to this?

I’ve been thinking about abortion a lot. I’ve been reading Roe and Casey and Dobbs, the majorities, the dissents, the amicus briefs. I’ve been immersed in Right to Life propaganda, anti-abortion horror films, abortion-neutral horror films (my favourite is Prevenge, a sort of reverse abortion plot in which a woman’s unborn child tells her to kill various arsey men, which she dutifully does; I also recommend the talking foetus in Blonde, so long as you regard it as a horror film rather than a biopic of Marilyn Monroe). I’ve read many, many descriptions of legal and illegal abortions in novels and medical literature and online testimonies, and in the end, I started dreaming them. For a while I had an abortion every night.

It was a kind of research – into plot. I was writing derivative fiction in my sleep. Sometimes the abortion took place in a dingy backstreet, performed by a filthy harridan; sometimes I was boiling in a bath necking a bottle of neat gin; sometimes I was throwing myself from my bike as I hurtled down the steepest of hills. In one surreal scenario I was in a clinic for a routine biopsy. I had said nothing about the fact that I was pregnant. The doctor saw the proto-being on her monitor and looked at me, over the stirrups. I looked hard back and managed to convey to her – wordlessly – that I would be grateful if she could get rid of it. Wordlessly, she did, with a small scrape of a tool. Meanwhile, people in uniform busied themselves with other stuff. It was a secret abortion carried out in public.

None of my abortions involved moral deliberation. Night after night I woke to the satisfaction of knowing that the thing had been accomplished. I was reminded of an essay called ‘Abortion for Beginners’, by the Canadian writer T.L. Cowan. Cowan writes that as a college student she became addicted to the morning after pill, ‘hooked on the smallest of abortions’. ‘I don’t know if I was ever pregnant,’ she says, ‘but I craved that crampy, decisive discharge for its own sake.’ As she tells the story, Cowan’s abortion compulsion is the natural outcome of her upbringing in an anti-abortion family. It’s an upward spiral. Taken by her parents, as a five or six-year-old, to demonstrate outside the Morgentaler abortion clinic in Toronto, she spies the counter-demonstrators, the lesbian feminists with their wire hangers: ‘There were dozens or even hundreds of them, all of those women together, and I couldn’t take my eyes off them.’ When her parents go out to screen anti-abortion films in village halls, she gets to fall in love with her babysitters: ‘ecstatic with their proximity – that they were in my house and their jeans were skintight … they were magical figures of glossy disdain, and abortion brought them to me.’

Cowan turns a queer move into a pirouette, reversing the negativity, the moralism and the trauma associated with abortion. The morning after pill is her gateway drug to becoming a lesbian. ‘Living in a family that taught me to hate queers as much as abortion, I needed to become an abortion before I could become a queer. I imagined myself never having been born, never having existed, in order to make a life full of queer impossibilities.’ But if queers and abortions are the same thing then abortion stories can learn from queer stories about turning the tables. Or we can learn how to read the stories right. Cowan offers an example of how to do this with Dirty Dancing, which stars Jennifer Gray as 17-year-old Frances, on holiday at a resort in the Catskills with her family in 1963. Early in the film Frances discovers the cabin where the staff are dirty dancing but she’s far too buttoned up to join in. She’s square and bad at moving her hips. But then, ‘the luckiest thing happens to Baby’ (you may have forgotten, but Frances’s nickname is Baby). Here is Cowan’s account:

She finds Penny crying in a heap and learns that she needs an abortion but that it’s impossible because it can only happen on a night when Johnny and Penny have a dancing gig at another resort and no one else can fill in for her because everyone else has to work. But Baby can do it because she doesn’t have to work! Do you remember the dance lesson scenes in the studio with Penny and Baby? Penny’s bodysuit. Baby’s knotted T-shirt and leotard. All of that steamy femme-on-femme screen time. Brought to us by abortion. The next fabulous thing to happen to Baby is that Penny’s abortion goes all wrong and Baby has to be very brave and get her doctor father to come to help to save Penny’s life. And then, as a reward for being so brave, Baby gets to lose her virginity! As it has been for me, abortion was so lucky for Baby.

Abortion turns out to be lucky, too, for the lovers in Céline Sciamma’s film Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019). We are in pre-revolutionary France and Marianne, a Parisian artist, has been ferried to an island off the coast of Brittany to paint a portrait of Héloïse. It is to be sent to Italy, to the man Héloïse’s parents have picked out for her to marry. This aristocratic-lineage forced-marriage plot is queered when Marianne and Héloïse fall for each other, over the maidservant Sophie’s abortion.

Sophie isn’t asked to give reasons for seeking an abortion. It’s enough that she doesn’t want to continue with the pregnancy. The two lovers bowl her back and forth over the beach, make herbal abortifacient tea and hang her from the rafters, but none of these methods works. (Dellapenna argues that since rudimentary abortion techniques often didn’t work they should be discounted as part of common law history – but the fact that many women tried them is the point. They tried them because sometimes they worked. They hoped the hot bath and gin, or swallowing ergot, or a fall down the stairs would ‘shift it’, as Doris Lessing’s neighbour Mrs Skeffington put it as she dusted herself off on the landing in the 1950s, and they were not dissuaded by moral misgivings about the origin of life.)

When these methods fail, the three women in Sciamma’s film visit the local handywoman, whose children help prepare the herbal paste that will be used to soften Sophie’s cervix. The handywoman’s baby gurgles on the bed during the procedure. I think what is happening during this scene is the manual manipulation of the uterus, an abortion technique that is described – with diagrams – in Taussig’s 1910 handbook for obstetricians. Taussig’s methods were intended to help practitioners faced with an incomplete spontaneous abortion, or a missed abortion – when the foetus dies without being expelled – or a retained placenta. But the book is also a record of what had been gathered about these techniques by the early years of the 20th century. It’s a record that stretches back in time but also forwards. As several historians have pointed out, the book was almost certainly used as a guide (‘how to plot an abortion’) by abortionists and women trying to help one another in the 1910s and 1920s.

The odd thing about the abortion in this film is that it happens twice, the second time as art. Héloïse makes Marianne watch the first abortion, painful and unpleasant though it is to observe, never mind undergo. Later, Héloïse insists on recreating it, positioning herself as the midwife/abortionist, and asks Marianne to paint the tableau. What is going on here? Looking isn’t enough, Sciamma is saying. It is the duty of the artist to represent the private and the hidden in public. Throughout the film these spaces have been mixed up. Marianne turns a reception room into a bedroom and painter’s studio; in the salon scene towards the end of the film intimate stories of lesbian desire are hung on the walls of a public exhibition. This is Sciamma’s representation of a world before Balzac’s dining room, or a world coterminous with it, but hidden, in which women’s lore and their support for one another form the bedrock of a common law existence that barely interacts with bourgeois structures. In this scenario, Sciamma’s handywoman is ancestor to Arthur Seaton’s aunt in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and Winny in Up the Junction. But I think we should be wary of plotting an unbroken line of everyday experience to hold out against the (public) legal history of the Dobbs ruling. We would be making a similar mistake to the Dobbs historians, who think they have traced an unbroken line of rhetoric through the past and are hanging on to it for dear life.

The painting of the abortion scene in Portrait of a Lady on Fire has as much to say about contemporary debates as about versions of history. We might think of Paula Rego, and her series of pastels executed in a fury in the second half of 1998, after the failure of the referendum to decriminalise abortion in Portugal. (It was eventually passed in 2007 and Rego’s images and her forthright discussion of them influenced the outcome.) Her drawings are of isolated women and girls waiting at home, twisted bodies with buckets, pillows, jugs and chairs. They are images of Denise Lesur; in fact, one of Rego’s girls is lying on her bed with her legs up against the wall. They are images of Rego’s teenage self, undergoing her own backstreet abortion in the 1950s, and they are a direct challenge to images of the disembodied foetus.

Like Rego’s work, the painting of the abortion in Sciamma’s film is a still life about still life, an homage to the lost voices of mute classes, an intervention in the public sphere that isn’t telling a story – it’s not so much narrated as made present. I’m pretty sure this scene was the kernel for my dream abortion in the clinic. The doctor and I were positioned much like Héloïse and Sophie, even down to the sheet. My dream was about a clandestine understanding between women inside the public space of the hospital. A clandestine practice that is, literally, a refusal of clan-destiny – the family plot. And that is also true of the queer relationship between Marianne and Héloïse. The two women lose each other (the metaphor is Orpheus losing Eurydice), but the film tracks two plots unfolding at the same time – one in which Héloïse goes to Milan to marry and reproduce; and one in which she remains true to her secret desire. The marriage plot wins in public, but it’s been fatally undermined.

When Cowan says that as a queer person she ‘is an abortion’, she is pointing out that she’s the errant cog in the family wheel, the end of genealogy, the nemesis of the realist novel and the real-life marriage plot. She’s the sense of an ending. And here I want to come back to Ernaux’s abortion, the one that is written twice: the second time as memoir. It is surprising to me that it has been so little remarked that Ernaux’s abortion memoir begins in an HIV clinic. We are in Paris in 1999 and she is waiting anxiously in the clinic for the results of her tests.

I kept picturing the same blurred scene – one Saturday and Sunday in July, the motions of lovemaking, the ejaculation. This scene, buried for months, was the reason for my being here today. I likened the embracing and writhing of naked bodies to a dance of death … Yet I couldn’t associate the two: lovemaking, warm skin and sperm and my presence in the waiting room. I couldn’t imagine sex ever being related to anything else.

Her tests are negative and as she goes down into the metro she realises that ‘I had lived through these events at Lariboisière Hospital the same way I had awaited Dr N’s verdict in 1963, swept by the same feelings of horror and disbelief.’ Nearly thirty years after first writing about it, the abortion comes back to her, the second time as HIV.

Ernaux writes her abortion the second time not as a protest against the world of middle-class education and the bourgeois novel, which has erased her experience, but as a challenge to the political language in which abortion has been framed in the struggle over legalisation. Much of her writing rests on an enabling foundational naivety, an insistence on returning to ‘the real’. She needs something unreal against which she can pitch her real, and in this case it’s the obfuscations of campaign feminism:

The fact that my personal experience of abortion, i.e. clandestinity, is a thing of the past does not seem a good enough reason to dismiss it. Paradoxically, when a new law abolishing discrimination is passed, former victims tend to remain silent on the grounds that ‘now it’s all over.’ So what went on is surrounded by the same veil of secrecy as before. Today abortion is no longer outlawed and this is precisely why I can afford to steer clear of the social views and inevitably stark formulas of the rebel 1970s – ‘abuse against women’ – and face the reality of this unforgettable event.

The reality she depicts is one in which Anne keeps failing to act. The crisis pregnancy genre seems to lend itself to narrative; it’s time-bound and suspenseful. The ‘plot’ of L’Événement has everything moving inevitably forward to a date in July 1964 when Anne must give birth, unless she can find a way out. But the real-life Ernaux seems to have objected to this narrative framework even at the time. She recalls the doctor she sees after the near fatal illegal procedure, who tells her she has ‘pulled through’ remarkably well. ‘Unwittingly he too was encouraging me to turn this painful experience into a personal victory’ – a novelistic narrative with a central character who struggles against the odds.

Ernaux interrupts this narrative drive with revisions, qualifications and second thoughts. She consults diaries and dates to justify the veracity of the writing. She keeps adding parentheses, new memories that substitute themselves for the old ones, as a way of keeping the writing as close to the lived experience as possible. Fact-checking doesn’t help. If she tries to revisit the places where the events happened, she becomes a ‘puppet re-enacting a scene’, or worse, memory fails her. She can’t find the café where she waited before the abortion. She can’t identify the right toilet. She keeps getting stuck in the story, unable to advance it, and this is in part because she experienced her pregnancy as something outside narrative, or outside time.

The abortion story quickens the pace of the plot, driving it on, but the pregnancy itself slows time. Time becomes ‘a shapeless entity’ growing inside her, infecting her with ‘sluggishness’ and ‘numbness’ and contributing to a strange lack of urgency despite the urgency. She delays the abortion and goes on holiday to the Massif Central when she must already be sixteen or seventeen weeks pregnant, simply because ‘I had never been to the mountains.’ She can’t think and she can’t act; she’s stuck in ‘an experience that sweeps through the body’. It is her body that compels her. That, I think, is why the memory begins in the HIV clinic, twinning her abortion with desire, recklessness, ‘bad’ choices, sex as sex unconnected to anything else, life or death. What Ernaux is trying to express here is a kind of pre-reflective choice, not a choice that can be explained in narrative terms. I’m reminded of a phrase of Sartre’s that Judith Butler uses when describing Simone de Beauvoir’s writing about becoming a woman: ‘We are a choice, and for us, to be is to choose ourselves.’ This is choice as a form of knowledge, an understanding of oneself, rather than deliberation.

Ernaux ends up in a hospital maternity ward following surgery for the retained placenta which was causing her to haemorrhage. She can hear the mothers and babies next door:

The newborn babies would cry intermittently. Although there was no cradle in my room, I too had delivered. I felt no different from the women in the next room. In fact, I was probably wiser because of the abortion. In my student bathroom, I had given birth to both life and death. For the first time I felt caught up in a line of women, future generations would pass through us.

We could think of L’Événement as another double-ended plot, one in which Ernaux gets to give birth and have an abortion at the same time. ‘You’re in labour!’ the abortionist says when she returns to have the probe reinserted after a few days, and here Ernaux appears to be holding on to the idea of reproductive futurity (the link with future generations) that Cowan so robustly defies. But it’s an abortion, not having a child, that establishes her genealogy with other women, and that seems to allow her the ‘we’, the composite female who narrates the story of postwar female experience in The Years.

Ernaux’s title, L’Événement, loudly recalls the student protests of May 1968, and the book offers a damning verdict on the limits of that social revolution. The young doctor who yells ‘I’m no fucking plumber!’ at her as she haemorrhages is ashamed when he discovers afterwards that Anne is ‘like him’, ‘from the same world’. ‘Why didn’t she tell me she was a student?’ he says to one of the nurses. Unlike working-class girls, students are allowed to make responsible choices, whatever they happen to be. But although this memoir is about experience, it isn’t really about that kind of subjectivity.

The film treats things rather differently. For good political reasons, given recent attacks on abortion rights in the US and elsewhere, Audrey Diwan aligns Anne’s experience with a woman’s right to deliberate, to choose between options. Anne has two pivotal conversations with men in positions of authority in which her need for an abortion is explicitly set up as a choice between her future and the life of the foetus. I want to have children someday, but not at the expense of my life, she says to the doctor, who is sympathetic but won’t risk imprisonment for her. Later, she says to her university professor – also sympathetic – that what she is going to do with her life now she is free of the pregnancy is write. I was reminded of Little Women, where we get both the marriage plot (the satisfactions of romance) and the writer plot (the consolation of art). If stories about abortion are stories of women quietly refusing the family plots laid out for them, writing their experience, creating their own fate, then they do start in 1868, with Little Women.

Motherhood versus art: it’s not the first time these two careers have been opposed to one another. And since Anne is Annie, Ernaux’s entire career is posited as a consequence of her assertion of her right to bodily autonomy. It’s quite a pay-off. Having the abortion not only frees her to write, but the next fabulous thing that happens is she gets a Nobel-Prize-winning subject.

In none of these stories – Sciamma, Cowan, Ernaux – is abortion justified. Instead, it is associated with desire, with a bodily compulsion. Sex and abortion are the same, they happen in the same place, Denise says in Les Armoires vides. I want to end with another thought about compulsion. Ernaux was writing her memoir in 1999 during the war in Kosovo and says that, as she writes, Kosovan refugees are trying to enter Britain illegally via Calais.

The smugglers are charging vast sums of money and some of them disappear before the crossing. Yet nothing will stop the Kosovars or any other poverty-stricken emigrants from fleeing their native country: it’s their sole means of survival. Today smugglers are vilified and pursued like abortionists were thirty years ago. No one questions the laws and world order that condone their existence. Yet surely, among those who trade in refugees, as among those who once traded in foetuses, there must be some sense of honour.

The abortionist and the people smuggler, like the pregnant woman, or the migrant compelled to seek their help, are the superficial actors in the story, but the root cause is illegality – the laws and world order which say that some people can have what they want just because they want it, and others have to deserve it – have to perform a need.

The law frames a particular kind of storytelling. Abortion is not legal in the UK, it is justified by a story. Everything depends on an ‘if’. What you are doing is wrong but we’ll allow it ‘if’. When you access an abortion, you are asked to take on the role of a character making a choice, full of thoughts and feelings that are explained and then justified: you are asked to tell a good story. The stories – the ones asked for by our legal structures – are compulsory. Indeed, they are life-saving. But if you try to fit your experience to a legal definition of rights, you are going to be telling the wrong story.

Every day we can read in the paper a new story: about the Florida teenager, a victim of incest, denied an abortion; the Tennessee woman whose waters broke at 23 weeks, forced to wait until labour occurred despite the risk of blood poisoning; the people who can afford neither contraception nor healthcare nor to feed the children they already have. When Alice Walker says, ‘Life is not a façade, there’s nothing behind Life,’ she’s talking among other things about a consciousness of individual destiny, and the drive to grasp it, to take control of your own fate, but she’s also saying: look around. None of this is invisible. You can see what’s real if you look.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.