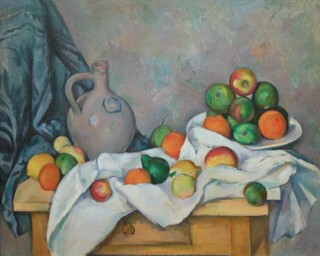

The pigments in paintings of Cezanne’s middle age cluster like gangs in a schoolyard. Cobalt, ultramarine and Prussian blue cleave to a bay or bolt of fabric. Emerald and viridian occupy pears, jars and foliage. The biggest grouping, the ochres and terracottas, huddle around roofs or rocks or bathers, while fiercer heats – oranges, lemons, apple reds – tear away from them, reaching for their respective fruits. How to make these fractious parties rub along is half the painter’s puzzle – in Curtain, Pitcher and a Fruit Bowl, a canvas from around 1894, a cushioning grey surface seems to aid his supervision. Nonetheless, the overall uproar is joyful. ‘He had no conception of beauty,’ Emile Bernard pronounced soon after Cezanne’s death. ‘He possessed only the idea of truth.’ This assessment, prompted by a letter in which Cezanne undertook to provide the young Bernard with ‘the truth in painting’, has lent generations of interpreters their cue. But fall in with the crowds visiting Cezanne, Tate Modern’s career-survey exhibition (revisionist in dropping the acute accent Cezanne acquired but never himself used), and the pace is frisky, not veridically grave. The zinging saturations, zooming this way and that, stir viewers. Whether or not they constitute beauty, they signal intensity – those hot, iron-rich pigments most of all. They attach themselves to desirables: to good fruit, to the good land of Provence, viewed under prevailingly fair skies.

We wander the galleries high-humouredly, yet often enough pulling a face. Cezanne’s private puzzling – just how should masses of lemon and lead white converse? – slips into provocative teasing. No, that plate on the right could hardly have perched in that way on a three-dimensional kitchen table, and yes, the fruit on it perform a balancing act that seems outright miraculous. But painters have always reserved the right to collage their observations, and Cezanne did so with particular vehemence. Let the shapes on the canvas spring away from one another with a tensile inner force: that remained Cezanne’s instinct throughout his career, from the figure-dominated work of his youth until his final collapse, aged 67, while working en plein air in 1906. Accustomed from childhood to baroque altarpieces and statuary, and finding that vein of taste commended by the mighty Delacroix, Cezanne always took it as read that his own work would obey expressive rhythms.

Sometimes his ‘expressive’ accelerates into ‘wilful’. The droller ventures on show at Tate Modern play with the question ‘Will this be a painting, if I paint it?’ An abrupt slice of Paris roofscape confronts us, perspectiveless and flattened, or we meet a clunky enlargement in oils of a plate from La Mode Illustrée, or another of a nude adapted from a champagne label, to which a study of pears has been glued in reverse orientation. The sense of humour here is gruff and oblique: at whom can it have been directed? At Louis-Auguste Cezanne, I suspect, tough Aixois businessman, tight paymaster to his disappointing son Paul. Look, papa, no less than you I am a free man, my art is at no one’s service. ‘The word employé seems disgusting to me,’ Cezanne wrote aged 29. The early work – tenebrous fantasias such as The Murder, painted at much the same period in his life – bristles with a defiant unmarketability. Yet long before he came into a comfortable inheritance in his forties, duty had caught him in a distinctive 19th-century hold. The freedom of the artist was to be interpreted as an exalted, lonely calling and, in tune with this age of scientific progress, as an unrolling programme of research.

The exhibition’s terrific display of 1890s still lifes, along with others focused on favoured landscapes and on Cezanne’s bathers compositions, show where that programme headed. (These thematic hangs follow some prefatory career-retracing.) Cezanne was bending assumptions familiar to his craft. In all these genres, painters expect to represent entities on which our eyes settle – objects, hillsides, bodies – by laying down alternative eye-stopping pigments. You might approach that laying down as a tiling job, slotting colours into the entities’ interrelating borders. Cezanne, however, came to treat it more like dry stone walling. His first datum was the resistant solid object. Could pigment be correspondingly concrete? Where the lemon arrests the eye with its firm skin, can chrome yellow bounce back at it with equivalent force?

But masses – lemons, pears and tablecloths – co-exist in space. How should yellows, greens and whites analogously jostle? Cezanne came to contend that, in principle, ‘line and modelling do not exist.’ A ‘no’, then, to art’s most familiar tools, and another to the alternative tactic of thinking in chiaroscuro: Cezanne claimed that ‘light does not exist’ either. The business of painters was with ‘planes represented by colour sensations’. What irrefutably presented itself, however (and here he saluted the insights of Pissarro and Monet, the colleagues he most respected), was ‘atmosphere’. It caused those colour sensations to grow bluer and dimmer as objects receded from view, allowing also for their interpenetration. Take the viewer into consideration, and the conundrums increase in complexity. It emerges that the secure facts – the solid objects – are tethered to a subjectivity that is fleeting. Each canvas from Cezanne’s early thirties onwards (the phase when Pissarro encouraged him to embrace plein air) explored these interdependencies, whether with stouter or more stuttery resolution. Memories of what masterpieces in the Louvre had looked like encouraged Cezanne to seek lucid structure and definition, but once he had embarked on his counterintuitive unravelling, no stable stylistic formula lay in sight.

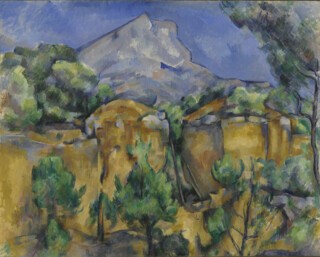

‘Cezanne’s doubt’, as Maurice Merleau-Ponty called it in an essay of 1945, is regularly taken as the tipping point for 20th-century painting’s tumbling dynamics. Less discussed are the beliefs that might have prompted Cezanne to embark on his inquiries. Behind the present survey hovers the ghost of a smaller exhibition that was unable, owing to lockdown, to transfer from Princeton University Art Museum to the Royal Academy in July 2020. Glancingly, the Tate Modern captioning alludes to its insights. The thesis of John Elderfield’s Cezanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings, which served as the Princeton show’s catalogue (Yale, £35), turned on Cezanne’s formative twenties, prior to his teaming up with Pissarro in Normandy. Back in Aix, his discussion circle had included not only Émile Zola, on a fast track to celebrity, but a formidable young scientist called Antoine-Fortuné Marion. It was Marion who alerted the group to the recent revolutions in thought advanced by Lyell and Darwin. Zola articulated their response in 1865: ‘I see in the study of geology a new faith, a faith both philosophical and religious.’ From that point onwards, Elderfield argues, Cezanne started to internalise this creed, and the Princeton show featured landscapes – whether painted around the Bay of L’Estaque near Marseilles, inside an abandoned quarry known as Bibémus, or looking east from Aix towards Mont Sainte-Victoire – in which he avowed his commitment to it explicitly. Many of these now appear at the Tate, with a wall text quoting Cezanne’s explanation that in order to paint the peak, he needed ‘to know some geology’.

Geology ponders matter and time. The substance of the world we live in is weighty and resistant. Its dominating features, the mountains, seem not to budge. But we accept that they have budged and continue to, and that the gradual alteration of morphologies among living beings feeds into those long processes of change. Great slow forces preside, moving heavily: here was a tenet fit for keen young readers in the 1860s, compatible enough with the vogues for positivist philosophy and Realist art. For Cezanne, it offered a gloss on the aggressive impulses already driving his work. In L’Estaque landscapes of around 1870, such as a Road with Trees in Rocky Mountains from Frankfurt’s Städel Museum, his slabbed, sludgy brushstrokes declare what Elderfield calls an ‘equivalence of paint and stony substance’. Matter remains unitary, whether it shows up in the form of rocks or the colourmen’s supplies. Either way, it kicks back at us. Mass equals pigment equals optical stimulus.

Yet matter consists also of momentum-charged bodies tensed against one another – in the picture, just as in the world beyond. Biological and indeed human agencies factor into this ‘struggle for existence’. The Bibémus paintings engage with long centuries of quarrymen’s assaults on the ‘living rock’ and the ways in which the resultant ruddy planes of limestone were grabbed back by resurgent green trees and scrub. The contention of opposing pigment masses doesn’t simply mull over the new ‘big history’ of 19th-century science – in the way, for instance, that the Scottish artist William Dyce had already done – but bids to impersonate and enact it, even to the point of melodrama. In the words of the artist Terry Winters, discussing the Princeton display with Elderfield, Cezanne ‘transforms a painting itself into a laminated, accumulated structure that’s an analogy to the way the earth itself was formed’.

I see that stratification as extending to the contour-warping of which Cezanne was so fond. In the little world of the picture, colour-clusters are enacting their own struggles for existence, negotiating trucial boundaries that may be fraught and writhing or – as with the still life’s conjunction of green fruit, white cloth and blond wood – orthogonally peremptory. Such fights between greens and yellows are properly speaking fights for the viewer’s attention, colour being (as we are all marginally aware) in some sense within the eye and inescapably mental in nature. Coherence demands that related dynamics operate either side of the retina, a homology with which Cezanne’s work complies. It expects the mind, no less than the world outside, to act as a slow stiff swirl of interlocking forces. Yearnings drive it. For many viewers, a high point of the show will be the tumultuous late 1890s composition from Baltimore, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from the Bibémus Quarry; while for at least some of us, its low point remains the National Gallery’s Grandes Baigneuses, a vast, wearisomely self-reproaching snarl-up of ochres and Prussian blue. In this painting, a sexagenarian scrabbles after an organising logic to his receding sensual dreams, whereas in Bibémus Quarry his handiwork feels exuberant, shimmering with the surprise of direct plein air encounter. Yet this Baltimore canvas may in fact have been a composite of studies (the curators seem to think so) and – with its upthrust of peak and subjacent central cleft – it analogously, only far more happily, accommodates dreams of sex.

The energies infusing the earth’s long history are equally coursing through our own veins. Rock and flesh are one – at least to the pictorial philosopher. Cezanne’s singularity was in aligning ardent independent thought with swingeing biases of eye and hand, in favour of those bouncing body-boundaries and of the chromatic intensities that lend his pictures their keen flavour. That singularity was also isolation. Cezanne was so little a ‘people person’. His wish may have been to address every genre, but as his biographer Alex Danchev puts it, ‘a Cezanne portrait is more a thereness than a likeness.’ Witness the implacably non-empathetic studies of Hortense, the woman he married. Only their adored son seems to slip under the defensive barriers behind which his father contemplated the world at large. Formal affinities were always for the taking in that comprehensive there. Each grab might be a register of the mind’s turbulent hereness, but the resulting painting would harmonise the to-and-fro, elevating it to some higher and happier plane.

This ambition to generalise could have settled down into a set of tactics for processing compliant materials. (Those admirable fruits, this dear land of Provence.) Switch from the painted oeuvre to the directives vouchsafed by the ageing recluse to whoever would listen and you catch hints for new and potentially seductive stylistic orthodoxies. But even as Cezanne was leaning on his late-arriving cult celebrity status to write to Bernard that he must ‘treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone,’ his brush was subverting his pen. The new ventures pursued at Les Lauves (the out-of-town studio built for Cezanne in 1901) – their chief subjects being his gardener and the already much studied mountain – bypassed his familiar stock-in-trade of concrete objects to concentrate on the mystery of atmosphere. In these jerky, straggly patchworks of quick brush-blasts, the puzzle seems to be: how, in the viewer’s eye, do colour planes attach themselves to nearer and to further? Yet with that came a fiercer stridency. The peak got pinched up higher and higher over a plain seen to apocalyptically dissolve. The empty windows of the deserted Château Noir, a site frequented during the same illness-shadowed years, mimic the eye sockets in concurrent studies of skulls.

Again, we might ask on what beliefs Cezanne was now acting. If his art spoke so urgently to 20th-century viewers, one reason might be that he thought hard about reality, and that his tilt from a physics of mass and momentum towards one allowing for the observer’s constructive role paralleled broader developments in thought. But clearly the work of Cezanne was not scientific, in any customary sense of the term. He set out as a young poet-painter lurching from reverie to reverie and if, en route, Marion and then Pissarro steered him towards more precise methodologies, their versions of materialism inspired because they seemed fertile metaphors. By his late fifties – the century’s end, by which time Cezanne had acquired a small audience – the dream had moved on and was starting to take a religious cast. The returning communicant remembered by Bernard now painted with one eye on fleshly transience, the other on what might endure: the mountain, the mission. ‘To see God’s work! That’s what I’m attempting.’ That promise of ‘truth in painting’ was intended with a prophet’s presumption.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.