In the spring of 1944, a young man was stopped at a checkpoint of the Pétainist milice outside the Saint-Germain-des-Prés metro station. According to his identity card, he was Julien Keller, aged seventeen, a dyer, born in the département of the Creuse. The bag he was carrying contained dozens of other fake identity papers. But he was confident that the police had no idea how frightened he was because he had learned to affect an air of serenity. ‘I also knew, with certainty, that my papers were in order,’ he recalled many years later. After all, ‘I was the one who had made them.’

‘Julien Keller’ was the nom de guerre of Adolfo Kaminsky, who died in Paris last month aged 97. It was largely thanks to him that the German-occupied zone of wartime France was flooded with false documents. The Occupation authorities were on his trail, but they never suspected that the forger they were after was a teenager. (He was actually eighteen, but claimed to be a year younger to avoid conscription into the Compulsory Work Service.) Kaminsky worked out of a laboratory on the rue des Saints-Pères, disguised as an artist’s studio. Housed in a tiny attic, it belonged to the ‘6th’, a secret section of the General Union of Israelites of France (UGIF), an organisation the Vichy regime had set up and financed with money and property confiscated from Jews. The UGIF pretended to be a humanitarian outfit but would be instrumental in organising the deportation of the Jewish population. The network of the 6th set out to undermine its parent organisation, resisting the Occupation and forging links with various Resistance groups: communists, Zionists and supporters of Charles de Gaulle. Over the course of the war, the 6th helped to save as many as ten thousand Jews from deportation.

Only four people worked in the lab. The director was a man known as Loutre (‘Otter’). Kaminsky’s assistants, the Schidlof sisters, Suzie and Herta, were students at the École des Beaux-Arts. This group was not the only one producing false documents, but it was unusually good at making them in large numbers. Most fake papers were made by falsifying existing documents. Kaminsky, however, had discovered a way of manufacturing new documents which, as he put it, looked ‘as real as if they had come out of the National Printing Office’.

Kaminsky described the work in his memoir, A Forger’s Life (2009), written with his daughter Sarah: ‘I dreaded the technical error, the small mistake, the tiny detail that could have escaped me. The slightest second of inattention can prove fatal, and on each piece of paper depends the life or death of a human being.’ He brought the same rigour to the forgeries he later produced for Algerian rebels, insurgents in Latin America and Africa, anti-apartheid activists and opponents of the dictatorships in Greece, Spain and Portugal.

As Hannah Arendt pointed out, to have ‘the right to have rights’ a person must belong to a political community, the surest proof of which is having the proper papers. Kaminsky learned this as a child. His parents were Russian Jews who met in Paris in 1916. They were forced to leave a year later, when the French government ordered the expulsion of all Russian nationals suspected of communist sympathies. Kaminsky’s father, Salomon, wasn’t a communist, but he’d been a member of the Bund, a Jewish socialist political organisation. Salomon and Anna Kaminsky moved to Buenos Aires, where they obtained citizenship, and where Adolfo was born in 1925. In 1932, they were allowed to return to France. They eventually settled in Vire, a town in Normandy where Anna’s younger brother, a French citizen and First World War veteran, ran a business.

Their lives were precarious, however, and Adolfo dropped out of school at thirteen to work in a factory that manufactured aircraft dashboards for the army. After France fell to the Germans in June 1940, Jews were banned from working in the factory, but he quickly found an apprenticeship with a chemical engineer who taught him the art of dyeing. He later described his wonder on seeing that, after a piece of clothing had been dyed black, ‘the water would become clear again, like spring water.’

Jews came under increasing restrictions, culminating in the imposition of the yellow star in 1942. The Kaminskys refused to wear it. They were Argentinian, after all: an employee at the police station told Salomon that they didn’t have to declare their religious identity. But Adolfo soon realised they were not going to be spared the regime’s violence. Jean Bayer, a Jewish fellow employee at the factory, was murdered by the police for his involvement in Resistance activities. Soon afterwards, Adolfo’s mother was found on the railway track, her head severed from her body. The official claim was that she had fallen from the train after mistaking the exit for the door to the toilet. Adolfo was convinced she had been thrown to her death.

His response was to immerse himself in his passion: chemistry. He purchased his first chemistry set from the local pharmacist, Monsieur Brancourt, who became his mentor. Brancourt turned out to be an agent for de Gaulle’s Deuxième Bureau, in regular contact with Resistance fighters who were carrying out acts of sabotage against German convoys in Normandy. Sensing that Kaminsky wasn’t content to ‘cry over my dead without doing anything’, Brancourt asked him if he would have any interest in making things that were ‘a little more dangerous than bars of soap’. Soon Kaminsky was building detonators and assisting the local maquis in sabotage operations. Although he thought of himself as a ‘pacifist’, he took satisfaction in resisting the Occupation. ‘For the first time, I no longer felt totally helpless over the death of my mother and my friend Jean. At least I had the feeling of avenging them.’

In October 1943, the rafle came to Vire. Salomon Kaminsky and his four children, among the few Jews remaining in the town, were taken to the Maladrerie prison in Caen, and then to Drancy, on the edge of Paris. Tens of thousands of Jews were deported from Drancy to Auschwitz-Birkenau and other concentration camps, and the Kaminskys might have been among them, had it not been for the efforts of Adolfo’s older brother, Paul, who successfully petitioned the Argentine consul in Paris. In January 1944, they were released. ‘Why us, and why not them?’ Adolfo wondered. In Paris, he bought chemistry books from bouquinistes along the Seine and taught himself to make explosives. But when a man known as Penguin (aka Marc Hamon) recruited him for the Resistance, he wasn’t interested in Kaminsky’s knowledge of explosives so much as his knowledge of dyes. The Resistance needed papers for passeurs at the border, for members parachuting in from the UK and for Jews at risk of deportation. Kaminsky proved remarkably resourceful and inventive. He created a centrifuge with a bicycle wheel, so that photosensitive liquid could be evenly distributed on photoengraving plates, and used a pipe to repolish papers that had been damaged by acid. Identity cards, marriage and baptism certificates, ration permits: Kaminsky learned to make them all.

As word of the Paris forger’s abilities spread in Resistance networks, the laboratory on the rue des Saints-Pères began to receive as many as five hundred orders a week, from Paris, the Southern Zone and London. On one occasion, Penguin told Kaminsky that a raid on Jewish homes in the Paris region was imminent, and they needed papers for three hundred Jewish children in three days. This meant nine hundred documents, and seemed impossible. But Kaminsky calculated that he could make thirty fake documents an hour and refused even to take a nap until they were done: if he slept for just an hour, he reckoned, thirty people would die. One of his colleagues had to remind him that ‘we need a forger, Adolfo, not another corpse.’ After the Liberation of Paris, he joined the French intelligence services, making papers for the Resistance members who were parachuting into Germany to track down concentration camps before the Nazis destroyed evidence of the extermination. ‘Everything a man keeps on himself, in cases of capture, can save his life,’ he said. ‘I had a week in which to invent for everyone a credible past and to create the proofs of it.’

Simply to offer to make papers for someone – Kaminsky paid house calls to many Jewish families, urging them to accept his help – was to put his life in a stranger’s hands. His warnings to Jews about the extermination camps were sometimes met with disbelief, even anger. In his memoir he remembers visiting Madame Drawda, a mother of four, who insisted she had no need of false documents since her family had been French for several generations and, in any case, all the talk of death camps was ‘Anglo-American propaganda’. Then she threatened to call the police. Over the course of the war, several of Kaminsky’s colleagues were murdered by the Gestapo, including Penguin, who was caught driving thirty children to safety in Switzerland. To avoid detection, Kaminsky learned to ‘transform myself into a shadow’.

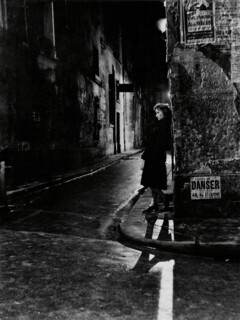

But the main lesson of his activities was that he could use his talents as a chemist and dyer to save lives. Forgery wasn’t just an art he had perfected; it was a vocation and an ethics. When his superiors in French intelligence asked him to take part in the campaign to preserve French rule in Indochina, he immediately quit. ‘The term did not yet exist at the time, but I was deeply anti-colonialist.’ Instead, Kaminsky pursued other interests. He climbed to the rooftops of Paris at night, taking haunting photographs of the city asleep, and ‘regaining my taste for life’. He married a Polish-Jewish woman, Jeanine Korngold, whose family had died in the camps; they had two children, Marthe and Serge. But the marriage fell apart and they divorced within a couple of years. Soon Kaminsky was drawn back to his work as a forger: he was too good to be ignored by those in need of papers. The first request came from a former Resistance comrade, Pierre Mouchenik, alias Pierrot, who requested papers for Jewish Displaced Persons seeking to go to Palestine. Kaminsky declined at first; he did not want to become involved in illegal activities. But when Pierrot took him to Germany in January 1946 to see one of the refugee camps, he changed his mind. The men and women he met had barely survived the war, and now wanted a new life in Palestine. ‘Personally, the place didn’t matter to me. I was not a Zionist. But I strongly defended the idea that each individual, particularly if he is being hunted and his life is in danger, should enjoy the right to move freely, to cross borders, to choose the destination of his exile.’

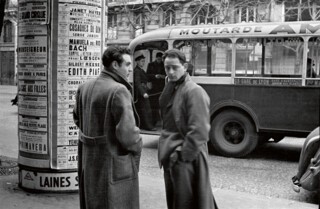

For the next two years, Kaminsky forged documents for the Haganah and its rivals in the Stern Gang, a terrorist militia led by Yitzhak Shamir, whose members included one of Kaminsky’s Resistance comrades, Ernest Appenzeller. In 1947, Kaminsky photographed Appenzeller and another Stern Gang member, Avner Grouchof, standing near a bus headed for the Gare de Lyon, next to posters for an Édith Piaf concert. With their overcoats and intent gazes, Appenzeller and Grouchof look like thugs in one of Jean-Pierre Melville’s gangster films. At the time, Kaminsky told himself that by supporting their efforts, he was helping to create a ‘Jewish-Arab country liberated from England’. There was more than a touch of wishful thinking here. But the Stern Gang’s commitment to terrorism did not sit well with him. When they asked him to create a time-delay system to be used in the assassination of Ernest Bevin, the British foreign secretary, he accepted the job – but built a mechanism designed never to detonate, and for good measure replaced the plastic component with a soft paste.

Kaminsky was ‘mortified’ by the 1948 war and even more so by the creation of a Jewish state. ‘I almost fell into Zionism,’ he confessed to the radio journalist Laure Adler in 2020, but the coarse anti-Arab racism he witnessed on a visit to Israel after the war quickly disabused him. ‘I couldn’t stand the new state choosing religion and individualism,’ he recalls in his memoir. ‘It was all that I hated.’ He never regretted having helped Jews to immigrate, but turned down repeated offers of a medal from Israel and refused ever to set foot there again.

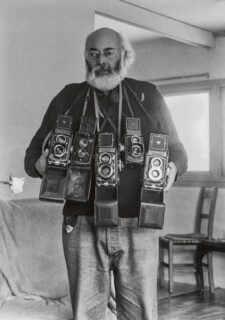

In the 1950s, Kaminsky established himself as a commercial photographer, with a studio on the rue des Jeûneurs. He took portraits, reproduced artworks and made film stills, collaborating with the set designer Alexandre Trauner on a film by Marcel Carné. His black and white photographs of prostitutes, street musicians, clochards and bouquinistes, which were shown at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme in 2019, display an elegance of composition and an affection for the Parisian demimonde reminiscent of Brassaï and Cartier-Bresson. He flirted with the idea of moving to New York, after falling in love with Sara Elizabeth Penn, a glamorous Black expatriate he met at a party. In 1957, Penn returned to New York, and waited for him to arrive.

He never did. Late that year, he received a visit from Annette Roger, a doctor from Marseille who was active in the porteurs de valises, a support network for the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), headed by the philosopher Francis Jeanson. The porteurs smuggled funds and documents, and provided safe passage and sanctuary for FLN activists throughout Western Europe. Roger asked Kaminsky about his work as a forger for the Resistance. When he had finished telling his story, she said: ‘And could you still make papers today?’ ‘If the cause justifies it,’ he replied.

Kaminsky hardly needed to be persuaded. He had witnessed the French administration’s oppression of Muslims while on holiday in Algeria in the early 1950s and felt ‘ashamed of being white’ and ‘ashamed of France’. Michèle Firk, alias Jeannette, a left-wing Jewish critic for the film journal Positif, became his principal contact among the porteurs de valises. They needed passports for Algerian officials being driven across the French border. The Swiss passport, according to Kaminsky, was the trickiest, and he wasn’t sure he could replicate it: ‘The texture of the cover, an ultra-light cardboard, both rigid and very flexible, containing embossed watermarks, was unlike any other.’

His studio on the rue des Jeûneurs was more than 150 square metres, and ostensibly devoted to his work as a photographer. The man he appointed as the head of his official business was a far-right supporter of French Algeria (‘I could not have dreamed of a better cover’). Kaminsky’s commercial photography subsidised his work for the FLN, for which he refused payment, saying it would make him feel like a mercenary. Offering his services for free also meant that he could suspend them ‘if the network [took] a turn that I disapproved of, for example, by organising terrorist attacks against civilians’. As Kaminsky points out in his memoir, the leaders of the porteurs were successful in persuading Omar Boudaoud, the leader of the FLN’s French Federation, not to carry out attacks against civilians inside France, and to focus instead on police, military and industrial targets.

Kaminsky’s past proved useful in other ways, since the people he’d helped were now indebted to him. When the network was looking for a safe house for a senior Algerian leader, he called on his friend Philippe, who lived in a sumptuous apartment in the 16th arrondissement. Philippe was a Jewish supporter of French rule in Algeria, but that made the idea only more irresistible to Kaminsky: who would ever think of looking for a senior FLN official at the home of a pro-French Algerian Jew? He also knew that Philippe couldn’t refuse him, since he had made papers for his entire family during the war. A week later – after a series of conversations with his FLN guest about classical music, philosophy, racism and their mutual resistance activities – Philippe rang up Kaminsky, singing the praises of the Algerian as ‘a man of great culture … If you have others like him, you can send them to me.’

Kaminsky also helped the FLN’s French Federation when it was seeking arms to defend Algerians against the settler terrorists of the OAS. Since the end of the war, he had been lugging around a stash of weapons belonging to Appenzeller. Over several days, he and a young FLN member, Belkacem Rhani, quietly moved the supplies. ‘Ernest’s weapons’ – the weapons of a Zionist militia member – ‘were henceforth going to serve the cause of Algerian independence.’

In 1961, Jeanson, who had gone underground after being convicted in absentia of high treason, relocated to Belgium. Kaminsky followed him, setting up his laboratory in Brussels. The French security services were closing in on the network: in October, Henri Curiel, an exiled Egyptian-Jewish communist who had replaced Jeanson as head of the porteurs, was captured and imprisoned at Fresnes, south of Paris, where hundreds of FLN activists were being detained. In Brussels, Kaminsky grew close to Boudaoud, a man of ‘serenity, intelligence and rapidity of judgment’ who admired him in turn as a Jewish résistant who had embraced the Algerian struggle. He and Boudaoud collaborated on the wildest act of forgery of the Algerian War: producing an enormous quantity of counterfeit francs in order to destabilise the French economy. But on 18 March 1962, the war ended with the proclamation of the Evian Accords between the French government and the FLN. Kaminsky and his partner at the time, an American surrealist painter called Gloria de Herrera, had to burn the money. (He hadn’t numbered the bills, as a precaution.) ‘I watched a year of work go up in flames,’ he recalled. ‘I liked … seeing the banknotes burn up.’ He was ‘elated’ at the thought of peace.

Some of Kaminsky’s French comrades, including Jeannette, went to Algeria as pieds rouges, hoping to build a socialist state. But Kaminsky declined to join them. He was appalled by the killings of thousands of Harkis – Algerians who had fought alongside the French – and even more appalled that his own government hadn’t provided those soldiers and their families with a safe haven in France. He returned to Paris in 1963 and resumed his work as a photographer, until a man calling himself Stéphane came to see him. He was a friend of Jeannette, he said. Georges Mattéi – his real name – was of Corsican descent, from a family of communist partisans. He was working with a new group, Solidarity, led by Curiel, who had been released after the Evian Accords.

For the next six years, Kaminsky became the Curiel network’s principal forger, making documents for Haitians opposed to Duvalier, Dominican critics of the Balaguer regime, ANC militants, Angolans, Bissau-Guineans and American war resisters. The German-Jewish activist Daniel Cohn-Bendit, who had been expelled by the French government, was able to slip back into France just in time for the events of 1968 thanks to Kaminsky’s artistry – ‘my only contribution to the May revolt’, Kaminsky said. (It was also a ‘gag’, he explained in his interview with Adler: it was the only time he made papers for someone who wasn’t in immediate danger.) He forged passports for Mexican activists after the 1968 student massacre, and for Czech dissidents after the crushing of the Prague Spring. All these rebels, with different and sometimes contradictory causes, had something in common: a Kaminsky passport.

For all the meticulousness of his forgeries, his domestic life was a mess. Herrera, from whom he had concealed his work for Solidarity (Kaminsky adhered to a code of complete secrecy, as he had since the war), thought he was spending his nights with an Angolan woman. (‘I have never succeeded in reconciling my clandestine activities and my romantic life,’ he notes in his memoirs.) She wasn’t entirely wrong in suspecting that his loyalties lay elsewhere. Nevertheless, towards the end of the 1960s, Kaminsky began to long for a life out of the shadows. In September 1968, Jeannette, who had joined the Revolutionary Armed Forces in Guatemala, shot herself in the mouth during a police raid. (She had taken part in the kidnapping of the American ambassador to Guatemala, John Gordon Mein, who was killed while trying to escape.) Kaminsky was disgusted by extreme left-wing groups like the Red Army Faction and their ‘bloody methods of urban guerrilla warfare’. He had also concluded that French security forces were following him. In December 1971 he paid a visit to Curiel’s home on the rue Rollin, where he deposited two suitcases filled with his equipment: his stamps, colouring formulas, blank papers, a heat machine for laminating covers. ‘Take care of it,’ he told Curiel, and then flew to Algiers. In 1978, Curiel was assassinated in the lift to his apartment by a group calling itself Delta, most likely embittered supporters of Algérie française within the French security services, possibly in collaboration with the apartheid regime in South Africa. The crime has never been solved.

Shortly after his arrival in Algiers, Kaminsky met Leïla Bendjebour, a law student, at a meeting in support of the Angolan independence struggle. Leïla had grown up in Blida, where Frantz Fanon had directed the psychiatric hospital in the early years of the war for independence. Her childhood neighbours were Jews: some had left for France at independence, but others had converted to Islam and remained. They married and had three children: Atahualpa, an engineer; José, a rapper whose stage name is Rocé; and Sarah, an actor and writer. Adolfo, who became a professor of photography, felt as if he’d been given ‘a bonus life’ in Algeria. For the first few years of their married life, the country was ‘culturally very free’, Leïla Kaminsky told me, even if the regime was deeply authoritarian. Houari Boumediene, the second president of independent Algeria, was a leader of the non-aligned movement, and the country was welcoming to foreign sympathisers, as well as to the leaders of national liberation movements, many of whom found sanctuary in Algiers. As a moudjahid, a veteran of the independence struggle and a symbol of the Algerian revolution’s international appeal, Kaminsky ‘lived like a king’, according to his son Rocé, and was embraced with ‘a rare fraternity by both the people and the state’. He was under no illusions about the FLN’s repressiveness or corruption, but counselled patience, since Algeria had only just achieved independence, and, besides, this wasn’t his battle.

Boumediene died in 1978, and his successor, Chadli Bendjedid, presided over the country’s Islamisation, building mosques and promoting an ostentatious piety. Algeria was suddenly awash in orthodoxy, encouraged by Wahhabist imams. Kaminsky was vulnerable: he was a foreign-born secular leftist and an intellectual; being Jewish didn’t count in his favour either. In 1981, one of his friends, a left-wing museum director, was assassinated. Three days later, Leïla was confronted at home by a group of men looking for ‘the professor’. The family immediately packed their suitcases and left Algeria, just as he’d left France a decade earlier. They settled in Thiais, in the Val de Marne, a southern suburb of Paris, where he found work as a counsellor, helping troubled youths in the banlieue of Kremlin-Bicêtre, many of them from North African families. He also taught them photography. And he continued to take pictures – ‘constantly’, according to Rocé.

In the introduction to his memoir, Sarah writes that if the family hadn’t moved to France, she might never have known about her father’s Resistance activities. Not that she heard it from him: he retained his habits of secrecy, hardly speaking to his children about his past until Sarah interviewed him for Une vie de faussaire. But his past would sometimes resurface, often despite his best efforts. Not long after his return to Paris, the far-right newspaper Minute informed its readers that an Algerian War ‘traitor’ had arrived in their midst, and that he was continuing to undermine France through his work with ‘delinquent’ North African youths. ‘The young people in Kremlin-Bicêtre read that article,’ Rocé told me, ‘and were kind enough to realise that some of their activities could sully my father’s reputation. They were much more careful to protect him, and not to disappoint him.’ While they still spent summers in Algeria, the Kaminskys made their lives in France, where, in 1992, they were naturalised as French citizens. Adolfo kept his distance from officialdom. When the ethnographer Germaine Tillion, a survivor of Ravensbrück, suggested that he be nominated for a Légion d’Honneur, he refused to be considered.

By the time I met Kaminsky, in 2019, at the flat in the 15th arrondissement where he and Leïla lived, he had lost some of his hearing; he sat in a corner, listening intently to his wife, who recounted their experiences in Algeria. But he was still very alert at 93, and, just before I left, spoke to me in an audible whisper about his life as a forger. He told me that he immediately broke off ties with the Zionist movement when he realised their intention was ‘to draw a dividing line between Arabs and Jews’. He remembered warning Curiel not to conduct his activities out in the open and said that he might have met the same fate if he hadn’t escaped to Algiers. I was struck by his long white beard, which seemed oddly rabbinic for someone so secular. He explained that in Drancy, with thousands of other Jews waiting to be ‘passé au four’ – put in the ovens – he saw an old man with a beard who was accompanied by a young girl. The next day, the man was on the list to be deported, and forced to shave his beard: ‘He was so weak that he was basically already dead. He haunted me then; he still haunts me today.’ He grew the beard after the war as a homage.

Kaminsky’s work on behalf of Algerians and other oppressed groups was also, he insisted, a tribute to the victims of Nazism. ‘My life as a forger [was] a long, uninterrupted resistance, because, after Nazism, I continued to resist inequality, segregation, racism, injustice, fascism and dictatorship.’ Kaminsky’s detractors couldn’t fathom why he would become entangled in distant conflicts, risking imprisonment or assassination. Some couldn’t see the unbroken thread that linked his anti-colonial resistance to his anti-fascism. The New York Times obituary hailed his work in saving Jews, but glossed over his association with the FLN and other national liberation movements. ‘I can’t vouch for every cause,’ the Paris-based journalist Pamela Druckerman wrote, rather primly, in a 2016 profile. ‘Some of the rebel groups he supported used violence.’ But so did the wartime Resistance, and in his anti-colonial commitments, Kaminsky wasn’t deviating from his past, but honouring it. Armed with paper and dyes, he fought ‘a reality that is too painful to observe or suffer without doing anything’, using ‘the only weapons at my disposal’. No one from the French government attended his burial at Père Lachaise; it was left to the Algerian ambassador to France to place a bunch of flowers at his grave.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.