Alexander the Great was a pioneer of political spin, a master of image-making. He permitted only a single court-approved sculptor, Lysippus, to do his portrait and took a team of propagandists and influencers on his invasion of Asia. On a medallion dating to late in his reign or just after, he appears in the guise of Zeus, holding a fiery thunderbolt – the first time a European monarch minted his own image. His widely circulated drachma coins, issued in a uniform design across his vast empire, show the profile of a beardless, youthful Heracles, with features so much resembling Alexander’s own that coin dealers today sometimes confuse the two. After Alexander died of a sudden illness in 323 bc, leaving no viable heir to the Macedonian throne or the headship of his immensely powerful army, his leading generals (the ‘successors’) ramped up this image-making campaign, drawing power from the myth of the man they had served for thirteen years.

Neither Alexander nor his generals could have imagined how spectacularly their publicity efforts would succeed. Over the decades and centuries that followed, his legend grew and ramified across the ancient world, taking on new features and larger dimensions. A pseudohistorical Greek novel of the second or third century bc, known today as the Alexander Romance, became a grab-bag of the welter of stories, as it crossed linguistic borders and accreted new strata, but even this proved insufficiently capacious; new tales arose in Jewish, Persian and early Christian traditions. With the advent of Islam, Alexander morphed into the Quranic Dhu’l-Qarnayn, or the Two-Horned One, a name possibly derived from Hellenistic Greek coins that showed Alexander with the ram’s horns of the god Ammon. From the Arab world he migrated to China as Dzo-k’at-ni, and versions of his story ultimately reached both the Malacca Sultanate in South-East Asia and the Mali Empire in West Africa.

To encompass this sprawling tradition in a single museum show is almost impossible, but the British Library has come very close. Deploying ‘objects from 25 countries in 21 languages’, Alexander the Great: The Making of a Myth (until 19 February), captures the kaleidoscopic diversity of the legend as it evolved over the course of millennia. The show has a roughly biographical structure, beginning with Alexander’s conception and ending, spectacularly, with an imaginative recreation of his burial chamber, the room constructed in Alexandria to display his mummified corpse. Along the way are books, manuscripts, a Babylonian cuneiform tablet, coins and medallions, an autograph score for Handel’s opera Alexander’s Feast, and a suit of armour decorated with scenes of Alexander’s campaigns, made for Prince Henry Frederick, the eldest son of James I.

Nearly all these portrayals show Alexander in a positive light, but the story told by modern historians and even some ancient ones is more complex. Alexander came to the throne of Macedon in 336 bc, aged twenty, after his father, Philip II, was assassinated at the height of his power. In order to secure control of the empire, Alexander resorted to cruelty, levelling the rebellious city of Thebes in an act of exemplary punishment. His march into Asia – an unprovoked attack on the Persian empire, though it was portrayed at the time as payback for the long-distant Persian invasion of Greece – exacted a huge toll in blood and culminated in the destruction by fire of the sumptuous palace complex at Persepolis. Neither of these razings gets much attention in the later legend, because they undermine the ideal of Alexander as an enlightened man, a ‘philosopher in arms’, as Plutarch called him. The texts that constitute the legend, as seen in the selection at the BL, prefer quieter, more personal episodes to large-scale violence: the young Alexander’s taming of the horse Bucephalas; his education under Aristotle; his devotion to his close friend (and possible lover) Hephaestion; his marriage to Roxane, an Iranian chieftain’s daughter. Such moments soften the hard edges of the historical record.

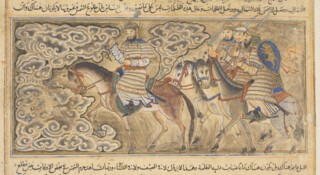

The spread of the Alexander legends is mirrored in the great theme of the legends themselves: Alexander’s travels beyond the known world. In reality Alexander was forced to turn back from his eastward march at the banks of the Hyphasis river (the modern Beas, a branch of the Indus), by troops who defied his orders to cross. But in fictionalised accounts, he continued further, sometimes on his own or with only a few companions, into a mysterious Land of Darkness or other vague and unmappable territories. The BL show includes two Iranian manuscript leaves, very different in style, depicting the journey. In the 14th-century Jami al-tawarikh (‘Compendium of Chronicles’), we see Alexander riding forward into swirling clouds of mist as three officers follow behind, their horses looking at one another in grim disbelief. A 17th-century work, the Khamsah (‘Five Poems’) of the Persian poet Nizami, captures a startling moment in the Land of Darkness, when Alexander’s men discover the Water of Life that confers immortality on anyone who drinks from it. Two prophets with blazing haloes are seen against a black background, examining a fish that has been revived by the water. Alexander looks on from a distance. The legends tell of various mishaps that prevented the water from reaching his lips, condemning him to an early death.

These voyages into the unknown promote the idea of Alexander, pupil of Aristotle, as a seeker of knowledge. A strange text first found embedded in the Alexander Romance, and later in stand-alone Latin and Old English versions, purports to be a letter from Alexander to Aristotle describing the wonders of ‘India’ (a term that, in this context, denotes a vaguely defined Far East). Manuscript illustrators delighted in the plethora of fabulous beasts and human grotesques that the letter records: dragons, griffins, sirens, wild men and women, and the comical Sciapods (‘shadow-feet’), contorting themselves to hold a single huge foot up in the air to act as a parasol. In some illustrations, Alexander is carried into the sky by huge birds, to survey the earth from above; in others, he descends in an ingenious submarine vessel to explore the ocean floor. Accompanying him on this journey, in a particularly beautiful page from a 15th-century French Roman d’Alexandre, are a rooster and a cat, brought along not as pets but to tell the time (in the belief that the rooster would still crow at dawn even under the sea) and recycle exhaled breath into fresh air (as it was then supposed cats could do).

Bizarre though they may seem, many of the legends have a kernel of lived experience, a subject touched on in many of the catalogue essays.* In Asia, Alexander did encounter animals that must have seemed monstrous to him, including monkeys that might have appeared like ‘wild men’. It has even been suggested, not implausibly, that the fable of the foot-shaded Sciapods arose from Alexander’s glimpses of yogis. In one case at least we can be certain of the correlation between fact and fantasy: Alexander’s encounters with the Gymnosophists, a sect of ascetics who, in many late antique and medieval texts, are depicted either welcoming the Macedonians or fiercely upbraiding their campaign of conquest. A passage preserved from the writings of Onesicritus, one of Alexander’s senior officers, reveals that such an encounter did in fact take place and that the invaders were tongue-lashed by a sect leader called Dindimus or Dandamis. This free-spoken holy man has served both Greek Cynics and early Church Fathers as a vessel for anti-materialist diatribes, a tradition still very much alive in 17th-century England, as seen in the BL’s copy of The Upright Lives of the Heathen from 1683.

The exhibition delights in these connections across time and space, especially those that show our own part in the chain of transmission. The curators have wisely included very recent materials, such as film clips and graphic novels, among the rare books and manuscripts. A scene excerpted from Michael Wood’s BBC documentary In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great (1998) shows an Iranian storyteller performing, before a rapt audience, Alexander’s legendary killing of Darius III, the last of the Achaemenid Persian kings. The scene makes Alexander directly responsible for Darius’ death, though we know from historical sources that, at the end of a high-speed pursuit, he found Darius already assassinated by his own entourage. Later writers couldn’t resist the drama of a final encounter between the two rulers, spinning the scene in various ways, though usually with Alexander showing tenderness towards the dying Darius. In an illumination of the Persian epic Shahnamah from 1604, he is seen cradling Darius’ head in his lap. The BBC film depicts a more bloodthirsty hero, even though the painted backdrop shows a similar head-cradling scene. The transmutations of history by the people of Iran, for whom Alexander was both an invader and a competent, tolerant ruler, are especially intriguing.

Recent treatments of Alexander, most prominently Oliver Stone’s 2004 biopic, have focused on his perceived homosexuality, though as Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones reminds us in the catalogue, ‘the queering of Alexander is anachronistic … The ancient Greeks and Macedonians had no word for [gay orientation], and no conception of it.’ The part of the BL’s show that deals with Alexander’s relationships focuses largely on his heterosexual loves (understandably, given the taboos throughout most of history on other kinds), but a personal letter from Mary Renault speaks to the way the figure of Bagoas, ‘a eunuch of remarkable beauty … who had been loved by Darius and was afterwards to be loved by Alexander’, inspired her to write The Persian Boy (1972). It’s clear from the letter, and from the novel, that Renault also considered Alexander’s attachment to Hephaestion, his friend from boyhood, to be erotic, though Llewellyn-Jones reminds us that the evidence on this point is scant and we are largely thrown back on surmise. A first edition of The Persian Boy is displayed in the show, and the catalogue notes that its appearance was nearly contemporaneous with the partial legalisation in Britain of male homosexuality. No causal link is drawn, but it’s safe to say (as Daniel Mendelsohn attested in a New Yorker essay of 2013), that in this arena particularly, the Alexander legend has not only stayed alive in the modern world but has helped to improve it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.