One of the more depressing aspects of the post-lockdown ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ phase was the abolition of the menu. On the dubious premise that handling them might transmit infection, menus were replaced, especially in pubs, by a QR code bathetically sellotaped to the table. Thus was lost a little more of the pleasure, the ceremony and the novelty of being catered for, and a little more was added to the amount of time everyone sat staring down at their phones. As often happens with restrictions imposed as emergency measures, it was not reversed when the emergency was over, having proved too useful to the people in charge. Pubs and restaurants struggling to get waiting staff have found it convenient to offload some of the work onto customers, who can choose and order as they will pay – contactlessly. The artistic heyday of the form, as the timespan of Menu Design in Europe suggests, was already over by the millennium, and the interesting menus have for some time been ‘the domain of serious collectors and institutions’, as Jim Heimann puts it. Not that either group will gain much from this immensely heavy, illustrated anthology. It is what used to be called a coffee-table book (though coffee tables seem to have gone out too), aimed at the non-expert browser, for whom it’s a delight. The text, which is replicated in English, French and German, takes a broad brush to ‘culinary history’, informing readers that ‘chefs were newly liberated from their ties to aristocratic families via the French Revolution and began preparing meals for private diners. Enter fine dining.’ After which there apparently ensued what Heimann describes as ‘centuries of gustatory elation’ and which the French renders less excitably as ‘plaisirs gustatifs’.

With an equally sweeping approach to geography, Heimann pays little attention to national cuisines within Europe, beyond acknowledging France as ‘the fountainhead’ of culinary distinction. French was the international language of food for centuries and features on menus from Spain to Scandinavia, though nowhere so much or so persistently as in Britain, where it signals a cringing sense of inferiority and the fond hope that anything described as ‘à la’ something else will sound sophisticated. Conversely when a French menu uses English it feels like an implicit snub. If France has no word for ‘pouding’ it is because it does not care to be associated with such a thing. Eighteenth-century England could boast food as good as any on the Continent, but industrialisation and depopulation of the countryside combined to fracture culinary traditions, ushering in the Victorian Age of Indigestion, when quantity had to stand for quality. It was perhaps after the Second World War and on into the early 1960s, when ingredients as well as professional cooks were in short supply, that British food reached its nadir. One sign of better and more cosmopolitan food is the gradual dwindling of menu French over time, though it lingers on in the socially aspirational world of rotary clubs, livery companies and Oxford colleges, giving birth to such chimeras as ‘dim sum de légumes avec daikon et gingembre confit’.

As physical items, menus seem to have taken permanent form only in the mid-19th century, replacing the handwritten list. Heimann has little to offer for the first decades of his period. His earliest example is a lithographed carte from the Hôtel du Commerce in Bruges. A massive baroque frame supporting a hefty cornucopia and looking unhappily like a memorial tablet surrounds the extensive list of dishes on offer for 7 February 1844. It promises to take diners through from turbot to kirsch jelly, but there are no prices. These were a surprisingly late introduction, and the first example here is from May 1906. The Carlton Restaurant in Wiesbaden, which boasted an elegant Wiener Werkstätte-inspired green and cream design, offered an all-inclusive dinner for four marks fifty, with individual plates mostly at two marks fifty, though what this meant in terms of relative expense is hard to know. The food is described in a bewildering concoction of Germano-franglais culminating in ‘Porterhousesteak à la Jardinière’, the elaboration perhaps a reflection of the price, which at eight marks made it the most expensive choice by some way.

The structure of the menu as a sequence of courses was both cause and consequence of the gradual disappearance through the 19th century of ‘French service’, in which all the dishes were presented simultaneously, and the rise of ‘Russian service’, which presented a meal in stages. This was soon felt to be more convenient for both private and public dining. The number of courses and their order varied as it still does with time and place, but the essential outline of the meal was established by the 1840s. One sad loss since then is the ‘entremet’, now almost extinct, though the menus preserve its fossil record. This civilised ‘in-between’, often a sorbet, was intended to ‘cleanse the palate’ after the main course and to prepare the digestive system for the onslaught of the grand finale. The meals themselves and their relative importance in the pattern of the day also shifted over time. The distinction between ‘dinner’, taken in the afternoon, and ‘supper’, the last, usually light, meal of the day, fades in the 19th century as dinner moves later. England enjoyed a brief moment at the forefront of gastronomic fashion around 1900 with the introduction of ‘five o’clock tea’, an Edwardian craze that soon spread abroad and was on offer in 1903 at the Casino San-Sebastian in Spain. The menus, designed in Paris, sport a heady mixture of Art Nouveau tropes – curling branches, sinuous fruit and a severe-looking woman with a harp. A later attempt by the Trocadero Grill Room in London in 1937 to imitate the success of afternoon tea with its own innovation of late dinner – to be known as ‘dinuit’ – did not catch on.

There are of course two kinds of menu, though Heimann makes no distinction between them: the restaurant or hotel menu that offers you a choice of meal for which you pay, and the set menu for a formal meal that announces like a theatre programme what you will be given. For this you might or might not pay. Some of the most elaborate menus are for such ceremonial dinners and are clearly intended to outlive the occasion and become treasured souvenirs. Edward VII, nickname ‘Tum Tum’, was a regular and enthusiastic guest of honour at these elaborate feasts. As Prince of Wales he sat down in Fishmongers’ Hall in 1865 to a ‘premier service’ of six kinds of fish and two soups. This was served – as was often the case at that time – in an intermediary form between French and Russian service where each course featured a collection of dishes, grouped by type. Given the venue the extent of seafood was to be expected but it was followed in ‘seconde service’ by venison, lamb cutlets, quails, ris d’agneau, ham, pullets and Perigord pâté, and concluded with a troisième service involving Pouding à la Windsor, one of a number of items on these menus that may puzzle the modern reader and which the text does not explain. Who knows what a Coventry Puff is, or a Fedora Pudding? Congress Tart sounds unappealing and it is unclear what the Haversnack café in London had in mind in 1966 in its offer of ‘Fruit Disc’ for 1/6d.

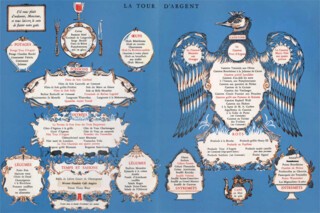

An advantage of the banquet type of menu is that it doesn’t matter whether you understand it or not: the food will come anyway. The restaurant menu, however, holds many pitfalls for those too young or socially awkward to ask questions. One solution is ‘a pictorial menu’, which, Heimann writes, ‘helps diners work their way through a meal’. This is true only up to a point in the case of the example he is describing, an elegant sky-blue double-page from La Tour d’Argent in the 1950s, where outlines of fish platters, vegetable tureens and a coffee cup suggest the nature of the dishes they enclose. But you would still need to know your Frédéric from your Sully when ordering the sole. The only really helpful menu illustrations are colour photographs of the real food but these, especially when laminated for easy wiping, are generally considered déclassé. Heimann is not a snob about them: he includes a 1976 table-mat menu from a McDonald’s in Switzerland, suggesting, with mild passive aggression, that the popularity of American fast food demonstrates the challenge it poses to the ‘culinary superiority of the Continent’.

Knowing which knives and forks to use, how to manipulate a lobster pick, avoid spaghetti whiplash and not to drink from the finger bowl are among the skills required in more formal settings, but there is always etiquette. It can be a faux pas to use cutlery at all if eating a burger; asking for a knife and fork in a Chinese restaurant can elicit a withering stare; and during the gastropub craze for serving food on boards, slates or anything except an actual plate, the smooth transfer of food to mouth required concentration. Context is all. A long menu may be high class, as at La Tour d’Argent, where it is the product of a kitchen full of expert chefs and fresh ingredients. In a more modest establishment a wide range of dishes means only a freezer and microwave out back. A small selection or even a single dish for the day may have more cachet. Heimann’s menus illustrate both extremes and with the dawn of the 20th century they move beyond banqueting halls and restaurants to include the bills of fare from liners, trains and, in their early and glamorous days, airlines. These are not always the most elegantly designed but are surely the most evocative. Setting off from Paris on 31 July 1912, in one of the Compagnie Wagons-Lits’ Grand Express Européens, it must have been thrilling to sit down to Potage Longchamps (pea soup), roast chicken and bombe glacée as the train rolled south. It is not an elaborate menu and the carte itself, surrounded by advertisements for Cointreau, scent and ‘automobiles Delaunay’ is of more period than artistic interest, but in those very details it conjures up the spirit of the age. Liners were equally glamorous and, as Heimann points out, after prohibition was introduced in the US in 1920, a cruise on a European ship held an added attraction for American tourists. The shipboard menus are also indicative of blunt class distinctions. The second-class traveller on the Lusitania in 1913 was offered a lunch menu of simple fare clearly considered suitable for the less sophisticated palette of what was assumed to be a monoglot traveller. Liver sausage and boiled beef are presented, like all the dishes, in plain English and there is semolina for pudding. Barely credible today are the delights of early airline food. As late as 1970 Air France was offering travellers from Heathrow a menu designed in the style of a couture house drawing, evocative scribbles in chic colourways suggesting an elegant woman in the modish trouser suit of the day. This is one of many frustrating examples where Heimann shows only the decorative part of the menu without the bill of fare, but it is notable that in this and other Air France designs from the 1950s onwards the imagined traveller is female and solo at a time when in many smart restaurants, if a man and woman dined together, it was usual to give the woman a menu with no prices marked.

In their graphics the menus reflect period more noticeably than nationality, though there are local peculiarities. The French have an odd passion for chubby children as ornaments, some of them so lusciously plump as to suggest they might be on the menu in more than one sense. Horribly cutesy cherubs or ‘petits marmitons’ in chefs’ hats and aprons, pink and white bottoms prominently displayed, adorn the carte of the Brasserie Lasserre in Paris in the mid-1930s. Ciro’s, a Parisian restaurant popular in the 1920s, favoured bewilderingly horrible pictures of fat toddlers, one biting another’s behind and another washing his bottom over a street drain watched by a stray dog, over the caption ‘La seule utilité de l’eau’. The prize for the most bizarre and off-putting association of ideas on a menu design also goes to France, for the dinners given to medical students by the manufacturers of Mictasol, ‘a tonic for urinary issues’, in the 1930s. Illustrations include a blushing Susanna and the Elders, in which Susanna’s crossed legs and downcast gaze suggest that the elders are not the only cause of her discomfort; a mannequin pis whose urine stream can hit a distant umbrella in the admiring crowd; and, most worryingly, a naked woman sobbing on her knees in front of an elderly gent proffering a phial of the miraculous cure.

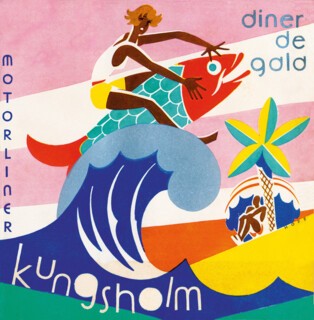

As a form of applied art, the menu took time to get into its stride. The earliest examples from the middle of the 19th century include some with paper edges pierced into lace patterns like doilies in an attempt at elegance quite at odds with the solid fare on offer. The menu for a second banquet in honour of Edward, Prince of Wales in 1876 has a magnificent border in red, gold, blue and green in the manner of Owen Jones, strongly reminiscent of the pumping station at the Crossness sewage works that the prince had opened, in the presence of its designer, Joseph Bazalgette, a decade earlier. Without doubt the heyday of menu design was the period between the world wars. Art Deco, with its flat planes and sharp lines and shadows, suited all graphics; it was a great age for posters and advertising art generally and it adapted itself to elegance as well as exuberance. A 1936 ‘diner de gala’ on board the Motorliner Kungsholm, a ship of the Swedish American Line, is one of the most joyous menus, with an outdoorsy looking young woman astride a leaping fish, and a man lounging under a palm tree on the horizon, all conjured up in a deceptively simple arrangement of areas of flat colour. Meanwhile at the Hôtels Splendide, Royal and Excelsior in Aix-les-Bains the same illustrative style creates a mood of icy chic: the impossibly tall, triangular diners, with snake hips and shoulders as wide as Wallis Simpson’s, gesture languidly and give the impression of people much too smart to eat. Food is presented variously over the years as status, as style, as fun, as sex and seduction, and, occasionally, as necessary to sustain life. In May 1941 the contents of an American Red Cross Standard Package No. 6 for Prisoner of War appear as a plain list starting with ‘Evaporated Milk, irradiated, 1 14.5 oz can’. It must have been as thrilling to the recipients as the most elaborate restaurant menu.

The Red Cross parcel shares the page with the menu for a feast given the following year at Santa Maria de Montserrat for General Franco to mark the second anniversary of his ‘liberation’ of Spain. It is decorated with wood engravings in a medievalising style, a virgin and child on the front. The occasion was, Heimann says, ‘a quasi-canonisation … complete with prayers, chants and a banquet’. Politics rarely features so directly in the menus, but food is always revealing of broader cultural attitudes and their occasionally dramatic shifts. There is much here to trouble the 21st-century reader. Gastronomically, perhaps the most horrible thing is the prevalence of turtle soup, the aspirational dish for much of the 19th century, which declined in popularity only because the turtle population diminished. The turtle usually arrived alive. ‘To make this soup with less difficulty,’ Mrs Beeton writes, ‘cut off the head … the preceding day. In the morning open the turtle by leaning heavily on it with a knife on the shell of the animal’s back, while you cut this off all round.’ Disturbing in a different way is the 1909 Carte des Vins of the Abbaye-Albert in Paris, featuring a man in evening dress with a moustache like a roguish grin and his arms round two women too drunk to resist his blandishments. Some menus are merely unfortunate. One’s heart goes out to the organisers of a dinner in Leeds on behalf of the trade body of funeral directors in December 1919 to celebrate the end of the Great War. Under crossed union flag and white ensign, the announcement of the British Undertakers’ Association Victory Dinner looks terribly wrong. A series of illustrations by the Belgian artist Charles van Roose for the Compagnie Maritime Belge of figures based on the people of the Belgian Congo are less forgivable and are the nastiest things in the book, until the next page, which features the menu for the Deutsche Arbeitsfront ‘party cruise’ in 1936, adorned with jaunty swastika flags.

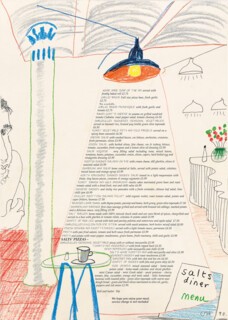

The later menus show British food improving as design generally declines in both quantity and quality. In less formal contexts, the idea of successive courses also fades and there is a return to a simple list of dishes that can be taken together or in any order. One of the last and most attractive, from 1993, is arranged in this way. David Hockney’s cheerful and practical design for Salts Diner, Shipley, in his native Yorkshire, has a long, flaring space in the middle to accommodate the changing menu, outlined as a pool of light beneath an overhead lamp. Everything is described in English and with a local clientele in mind. Salade Niçoise, they are reassured, is ‘very filling’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.