It was breakfast time in the Europejski Hotel, that cold November morning in Warsaw forty years ago, when the waitresses suddenly stood still. Their eyes widened; they turned towards the radio. One of them softly began to sing along with the march now blaring across the room. But how did she, born a dozen years after Poland’s communist regime banned them, know those words and that melody? ‘My, Pierwsza Brygada’ – ‘We, the First Brigade’.

It was the anthem of Józef Piłsudski and his Polish Legions. Piłsudski was the liberator of his nation in 1918 and its dominant figure – sometimes an offstage giant, sometimes a reluctant dictator – until his death in 1935. After the Second World War, Poland’s communist rulers suggested that he had been a fascist, which he never was. Piłsudski accepted diversity and usually respected minorities, especially Poland’s large Jewish population, which gave him electoral support. Liberals and socialists saw him as an enemy of parliamentary democracy; it would be fairer to say that he had nothing against elected parliaments so long as they stopped chattering and contradicting him and – above all – kept their hands off his precious army. Many Poles have called his ambition to make Poland a great power between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union delusory, and they have a point. But none of the complaints loosens the grip of Piłsudski’s legend on the patriotic imagination.

Around the Europejski that day in 1981, the passionate first year of Solidarity was at its climax. Outside food shops, women had huddled all night on frosty pavements in the hope of a few slices of sausage. In the morning, 11 November was restored as Independence Day, commemorating the moment in 1918 when Piłsudski took over military command from Poland’s foreign occupiers, and that evening a huge patriotic demonstration swept through Warsaw, chanting slogans against ‘the Russians, the Muscovites’ whom Piłsudski had always seen as Poland’s real enemies. Something, surely, had to give way. And, though only a few anticipated it, the Solidarity year collapsed just four weeks later into martial law, tanks on the streets, mass arrests, darkness and silence.

The source of Piłsudski’s charisma was not just personal, though he was a natural leader convinced of his messianic destiny to save his country. It also sprang from the glamour of his sheer anachronism. He brought back to life a rebellious, romantic, sacrificial tradition that most sophisticated Poles had decided, reverently and reluctantly, to leave in the past. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which once stretched over much of Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania, had been wiped off the map in 1795 and partitioned between the Russian, Prussian and Austrian empires.* Desperate uprisings in 1794, 1830 and 1863 had been suppressed and the elite of great and small gentry who led them were killed, dispossessed, deported to Siberia or given asylum in Western European countries. But in the late 19th century, a rueful reaction to all this urged Poles to accept the reality of the partitions, to forget fantasies of armed insurrection and to concentrate instead on ‘organic work’ to modernise Poland’s backward economy. No more national tragedies, no more bloody shirts to be shown to a boy when he grew old enough to keep secrets. Warsaw Positivism needed pragmatists, not martyrs. A bourgeois elite that could plan, invest and research began to multiply in towns and cities. So did a new industrial working class.

But Piłsudski sensed how fragile this new order was, and triumphantly appealed across it to history. ‘Our nation is like lava,’ the poet Adam Mickiewicz had written, ‘Its surface dry and withered,/But the inner fire still burns after a hundred years./Let’s spit on that crust, and plunge through.’ Born in 1867, only four years after the January Rising in which his father had been involved, Piłsudski came from a family of landowning gentry in what is now Lithuania, and was raised in a tradition of conspiracy and vengeful hatred of Russia. When the 1863 rising failed, ten thousand fighters lay dead, with 669 executed as traitors to the tsar and nearly 27,000 marched off to Siberian slavery or exile. In Piłsudski’s region alone, 1800 Polish estates were seized.

His mother read forbidden patriotic poetry to her children. Her moral teaching, as Józef remembered it, was that ‘only he is worthy to be called a human being who has a sure conviction and succeeds … in action without regard for the consequences.’ Nothing pragmatic about that! But another source of Piłsudski’s charisma was his ‘frontier provenance’; the hyperpatriotism of borderland people settled among ‘alien’ majorities. In the old Commonwealth, Polish settlers had become the dominant landowning class in much of western Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania. Reinforced by local nobility who adopted Polish culture, language and the Catholic faith, they were surrounded by peasantries speaking another language and often practising another religion. The old Anglo-Irish gentry, separated by language, religion and power from the majority and yet often defiantly asserting an Irish identity, offer similarities (one of them a gift for imagination ‘without regard for the consequences’: think Joyce, Yeats and Shaw, or Czesław Miłosz and Mickiewicz himself). Piłsudski’s own beloved home city was Wilno, now Vilnius and the capital of an independent Lithuanian republic. But his Wilno, for centuries the Commonwealth’s second capital, was very different: 40 per cent of its people spoke Yiddish, 31 per cent Polish and only 2 per cent the ‘country tongue’ of Lithuanian. It never occurred to Piłsudski that a resurrected Poland could be anything but multicultural, with Lithuanians, Ukrainians and Jews playing an active part under some sort of Polish hegemony.

As schoolboys punished for daring to speak Polish, he and his older brother, Bronisław, produced a handwritten patriotic newspaper. Józef chose Napoleon as his hero: ‘All my dreams were then concentrated around an insurrection and an armed struggle with the Muscovites.’ He recalled that ‘some time between the ages of seven and nine, I decided that if I was still alive at the age of fifteen … then I would lead an uprising and throw out the Muscovites.’ In his teens, he was already a member of clandestine nationalist groups and eagerly reading the torrent of forbidden literature smudgily printed in Wilno or Warsaw, or smuggled across the frontier. It was the age of bibuła (literally, ‘blotting paper’), meaning ‘banned writing’. Russian border guards grew used to the approach of amazingly thickset Polish ladies. Given a good shake, a slim but defiant girl would emerge as volumes of August Bebel’s Women and Socialism thundered to the floor. Piłsudski’s first wife, Maria, was a Bebel mule.

‘By age sixteen, in the fall of 1884, Piłsudski began to identify as a socialist,’ Joshua Zimmerman writes in his new biography. For Piłsudski and his brother, ‘the embrace of socialism reflected dual aspirations for national sovereignty and democratic society. The two concepts became inextricably linked.’ Linked – but which came first? Was independence the precondition for social justice, or was it the other way round, that only a social revolution could open the path to national independence? This became the most bitter controversy of Piłsudski’s early career, and it’s far from dead today. Nicola Sturgeon, for instance, repeats the argument that Scottish independence is instrumental: not an end in itself, but the indispensable means to achieve a just society. Her radical critics are Piłsudskian: independence is their final goal, while socialism – some upheaval in the distribution of wealth and power – might help bring it about.

But now the young Piłsudski fell into the rapids of history. In 1887, Bronisław had been involved in the failed People’s Will plot to kill the tsar (Lenin’s older brother was one of those hanged) and was sentenced to fifteen years’ hard labour in Siberia. Józef, who had done little more than share his brother’s house in Wilno, was sentenced to five years’ Siberian exile at Kirensk, a thousand kilometres north of Irkutsk. There he spent much of the time reading and listening to survivors from previous generations of Polish exiles: heroes of 1863 or socialist pioneers. When he was allowed to return to Wilno in 1892, family and friends didn’t recognise him: his front teeth had been knocked out by Russian soldiers in a prison riot, and he had ‘a face the colour of unclean copper’. Hopes that he might ‘settle down’ were vain, and a few months later he joined the newly founded Polish Socialist Party (PPS). Its manifesto called for socialism in an independent Poland, on the old Commonwealth frontiers of 1795, and its first purpose was to fight against the Russification of the Jewish, Ukrainian and Lithuanian minorities.

Again, it was a question of priorities. The powerful Jewish revolutionary groups in Wilno and Warsaw tended to speak in Yiddish and read in Russian; their instinct was to ally with Russian conspirators to overthrow the tsar and the whole structure of imperial tyranny. Polish independence might be a consequence, but it was not their central aim. A few years later, Rosa Luxemburg – also Polish-Jewish by origin – would declare that Polish independence was ‘a utopian mirage, a delusion of the workers, to distract them from their class struggle’. Piłsudski’s response was to establish pro-independence Yiddish books and journals in Lithuania and Poland, partly funded and printed abroad by the Polish-Jewish community in New York. In 1896, he fought out his disagreement with Luxemburg at the congress of the Second Socialist International in London, coming away with a disappointing compromise resolution which confirmed his view that Western countries – Ireland excepted – ‘have enjoyed sovereignty so long that they do not know [national] oppression’. By now, Piłsudski was producing an illegal PPS journal called Robotnik on a secret printing press in Wilno, and in 1898 he used it to preach the need to root out antisemitism: a disease, as he saw it, born of antique prejudice, capitalism and the reactionary politics of rulers like the tsar.

Zimmerman has made Piłsudski’s mostly supportive dealings with the Jewish community, and its experience of antisemitism, a central theme of his book. This tends to crowd out his treatment of other topics or minorities, but it’s good that Piłsudski’s long alliance with Jewish and other non-Polish parties should be more widely known. Necessary, too, though shocking, is Zimmerman’s detailed account of the pogroms that broke out as Poland regained independence, crimes Piłsudski condemned but was curiously slow to halt. Perhaps he never quite lost his doubts about whether Jewish loyalty lay with Poland or Russia, either tsarist or Bolshevik. He certainly failed to muffle the gross antisemitism of some of his military comrades, and later of his successors.

His vision of a resurrected Poland was always multi-ethnic and loosely federal, but the rise of Lithuanian nationalism worried him. Like Jewish radicalism, it seemed to look towards association with a democratic Russia rather than a free Poland. ‘To a large degree, Lithuania is a continuation of Poland,’ he wrote, but ‘the best plan with Poland is to ensure free development to the Poles, Lithuanians, Belarusians and Jews, and to do away with the great advantage of one people over another.’ A federation, an association of independent nations or a single state with self-governing minority regions? He never finally decided.

His lifelong rival and adversary Roman Dmowski stood for ‘modern, scientific’ nationalism: the exclusive version based on race, force and mass unity that developed in the 19th century. Deeply influential on Polish thinking to this day – his legacy is possibly even more lasting than Piłsudski’s – Dmowski is no more than an ever present shadow in this book. Piłsudski inherited from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth an old-fashioned, inclusive, political nationalism that was a matter of loyalty and flags, rather than genetics and culture. In contrast, Dmowski and his National Democrats wanted an independent Poland reserved for Catholic Poles who spoke Polish. Homogeneity was all: ethnic minorities, especially Jews (Dmowski was bitterly antisemitic), were a menace to the growth of a strong nation. To the National Democrats, Germany – not Russia – was Poland’s real foe. (Much later, the only fault many National Democrats found with the Nazis was that they were German.)

Although it dominated right-wing politics for nearly a century, Dmowski’s party – blocked by the centre and left parties, by the minorities and by Piłsudski himself – never won parliamentary power in a free Poland. Yet the shape of today’s Poland is Dmowski’s rather than Piłsudski’s. Churchill was one of many statesmen who shared Dmowski’s approach to nationhood. Remorseful over abandoning Poland to Soviet imperialism in 1945, Churchill thought he was compensating Poland by ensuring that the displaced, mutilated nation that emerged from the war would at least be ethnically homogeneous: a country overwhelmingly Polish, stripped of its Slavic minorities to the east and of six million Germans in the new territories to the west. Of Piłsudski’s expansive multinational vision, nothing remained.

In 1899, Piłsudski married Maria Juszkiewicz, the Bebel mule, in a wedding that parodied its time and place. Maria was a divorcée, so they staged a conversion to Protestantism; both were being hunted by the police, so they married under false names. They moved to Łódź, escorting the Robotnik printing press to their flat, but a few months later tsarist agents burst in and arrested them. Maria was released after eleven months. Her husband – now the driving force in the PPS central committee – was jailed in Warsaw and then St Petersburg but escaped by faking mental illness, then walking out of the Nicholas and Miracle Maker Hospital for the Insane disguised as a clinic orderly. By June 1901, he was back in Poland, in Austrian-occupied Galicia.

Antonia Domańska, an actress who met him then, recalled ‘classic features, steely eyes with a deep and penetrating look. He had lovely hands with a strong grip.’ Piłsudski was irresistible in small groups, though less at ease with vast crowds. ‘God, what a crazy pipe-dream,’ Domańska wrote, ‘but when he speaks one believes that there will not be Galicia but only a free Poland. He is simply obsessed with the vision of casting off chains.’ He returned to Wilno, still wrestling with the politics of the non-Polish minorities. Russian and Jewish socialists, he wrote, wanted ‘the transformation of imperial Russia into a democratic, constitutional republic’. His Polish socialists, by contrast, wanted ‘the total break-up of this house of captivity in which peoples and nations are suffocating. We strive for the total shattering of the chains that torment subjugated nations.’ After the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, Piłsudski set off for Tokyo, hoping to persuade the Japanese government to support a Polish rising against the tsarist empire. But Dmowski had got there first, and had warned the Japanese to have nothing to do with Piłsudski, whom he dismissed as a ‘brave boy, the son of a mother-patriot, who dreams of the liberation of his homeland’.

That war changed Piłsudski’s thinking. A mass popular uprising, in the 1863 tradition, was futile. Instead, there must be a professional Polish army, trained to defeat its partition enemies when the moment came. Meanwhile, the armed units he set up concentrated on local battles with tsarist police and on ‘expropriations’ – bank raids. The 1905 Russian revolution came and went, raising false hopes among Polish socialists. Piłsudski saw at once that nothing lasting would come of it, but he was increasingly isolated in his insistence on armed force, ‘pacing back and forth, smoking cigarette after cigarette, and drinking an inordinate amount of tea’. It was around this time that he went to inspect his secret arms dump in Warsaw and met Alexandra Szczerbińska. At 23, she was already in charge, issuing fighters with guns and ammunition. ‘I remember that my first thought of him was that here was a man whom Siberia had failed to break,’ she wrote much later. ‘Then I became aware of the tremendous force of his personality, of that indefinable magnetism.’

They did not marry until 1921, after Maria died. But as armed robbers, they soon became legend. A Polish Bonnie and Clyde? Alexandra was far more resourceful than Bonnie. In the great Bezdany train robbery of 1908, when Piłsudski and his ‘gang’ – four of them women – held up the Petersburg express with gunfire and bombs, blasting open caskets in the mail coach and flinging sacks of banknotes and silver onto the tracks, it was Alexandra who helped whisk the money away to a nearby forest and bury it. And it was she who came back, two months later, to dig it up and arrange for it to be smuggled across the Austro-Hungarian border to Kraków.

But by now something bigger – something incredible – was moving. The partition powers were falling out. Russia was losing patience with Austria-Hungary, outraged at its reckless imperialism in the Balkans, and in 1909, a year after Bezdany, Piłsudski began secret talks with Austrian intelligence officers. Suppose there was war with Russia. Suppose he could lead a Polish force – to be trained and armed in Austrian Poland – to support Austria with a rising in Russian-held Poland. The plan went ahead, and soon he was taking the salute as blue-uniformed Polish strzelcy (riflemen) paraded past him. Only the National Democrats, with their tilt towards Russia, held back.

Piłsudski had never been to university, let alone staff college. Now he furiously set to reading manuals of military doctrine and campaign memoirs. Zimmerman notes his ‘emerging belief that routing Russian forces from Polish lands was to be achieved not by insurrection but as a result of war with a neighbouring great power’. But would allying with one oppressor – Austria-Hungary – against another lead to Polish independence? Highly uncertain, but a chance not to be missed. By 1913 he was ready. Unexpectedly, he turned out to have an astonishing gift for predicting international affairs: he warned not only that an Austrian-Russian war over the Balkans was imminent, but that Germany and then France and Britain would be drawn into a European conflict. He even saw that the United States would sooner or later join the Franco-British alliance. At first, few Poles shared his optimism. Joseph Conrad, meeting gloomily with Kraków friends as war broke out, thought that it presaged the total dominion of great powers over lesser European nationalities: the extinction of Polish hopes for ever.

The war came, and then the iconic day of 6 August 1914, when free Polish soldiers tramped across the Austrian border and invaded Russian Poland. Piłsudski proclaimed that they were the army of a revolutionary national government in Warsaw. No such government existed, and that wasn’t the only thing his enemies found to debunk. Only four hundred soldiers marched, equipped with obsolete Werndl rifles; the cavalry consisted of eight men and three horses, with five troopers carrying their saddles and hoping to grab a mount in the villages ahead. Nonetheless, they reached Kielce in central Poland, where Piłsudski threw out the Russian governor and installed himself. Foreseeing retribution, the local Poles weren’t delighted to be liberated, while the Austrians warned Piłsudski to come back and obey orders. But matters quickly improved, as his growing force learned to fight (and as he discovered his own gift for leadership during and after battle). His next campaign, in Galicia, won him not only fame but widespread patriotic support.

By themselves, the Polish Legions, as they came to be known, had little impact on the war. It was the Russian Revolution that ended fighting on the Eastern Front and offered independence to Russia’s western nationalities: Finland, the Baltic republics, Ukraine and Poland. All three partition powers had made unconvincing offers of autonomy to Poland during the war. Now the Germans, who controlled Warsaw, tried again to recruit Piłsudski, though it was obvious that his political sympathies lay with Britain and France. His alliance with Austria-Hungary against Russia had been purely tactical. There was no longer any need for it, or for German concessions. (Back in 1915 he had predicted the defeat of the Central Powers, after a Russian revolution that would spread to Austria-Hungary, Germany and – his only mistake – Italy.) After many attempts to enlist him in a dummy council of state, the Germans arrested him in July 1917, interned his men, and sent him to fortress imprisonment in Magdeburg. There he stayed, fuming, for the last year of the war. But the cult of the ‘commandant’ was now firmly rooted, and not just in Poland. Zimmerman quotes the New York Times: ‘The Austro-German masters have dared to lay their hands on a man of whom the entire Polish nation is proud and who, in a sense, is the living symbol of Polish independence.’ He was released on 8 November 1918, as Germany fell apart in revolution. Back in Warsaw, greeted by ecstatic crowds, he accepted the role of commander of the armed forces and provisional head of state. On 11 November, as news of the Armistice arrived, Poland proclaimed its independence after 123 years of partition.

Piłsudski was now, as he said himself, in effect dictator. But the word dyktator in Polish is not uniquely negative. It can have a Roman-Republican meaning – a leader given total power by the people in a desperate emergency – and songs about Tadeusz Kościuszko, hero-commander of the first great insurrection in 1794, praise him with that title. Dyktator Piłsudski now faced at least three monstrous problems. First, he had to secure international recognition. The Entente allies had been dealing with a National Committee in exile in Paris led by his arch-rival Dmowski and the great pianist Ignacy Paderewski, and it took a year of haggling and lobbying before a united delegation, from Warsaw and Paris, could be recognised at the Versailles peace negotiations. Second, where were Poland’s frontiers to be? President Woodrow Wilson, the stoutest friend of Polish independence, wanted them to enclose ‘territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations’, with a corridor to the Baltic Sea. The Versailles delegates drew lines on maps; the new League of Nations organised plebiscites and peacekeeping forces. But in the event, the borders were set – if not settled – by bloodshed. There was savage war with the Germans in Upper Silesia, conflict with the Czechs in Teschen. Polish soldiers and student volunteers seized back East Galicia from briefly independent Ukraine. In Lithuania, now a sovereign republic, the Poles threw out a Russian Bolshevik force and then, in late 1920, staged a ‘spontaneous’ uprising that seized Wilno and its region and annexed them to Poland. Germany refused to recognise Poland’s new western frontiers, while Ukrainian nationalism (encouraged by repression in Poland) spawned an often murderous resistance movement. In several recaptured cities, anti-Jewish pogroms were led by Polish soldiers, provoking the Versailles powers to impose a much resented Minorities Treaty on Poland.

Piłsudski’s multinational Poland was emerging – but in an imperial, unstable shape challenged by its neighbours. The biggest of these neighbours was the new Soviet Union. Shrewdly enough, Piłsudski had refused to have anything to do with the Western intervention to support the Whites in the Russian Civil War. But, determined to establish an independent Ukraine as a buffer-state ally between Russia and the West, he sent troops to help the Ukrainian government expel the Bolsheviks. In May 1920, Polish soldiers rode triumphantly into Kyiv. As Zimmerman says, his critics at home cautioned that the Kyiv campaign ‘constituted reckless overreach’, and later that month the Soviet Union struck back.

The Polish-Soviet war of 1920 was short and spectacular. Mikhail Tukhachevsky in the north and Marshal Budyenny’s Red Cavalry horse-army in the south burst across Poland, and by August were at the suburbs of Warsaw. But Piłsudski had assembled a strike force and on 16 August his counter-offensive tore across the rear of the Soviet armies, cutting them off from reinforcements or supplies. They disintegrated. Thousands fled into East Prussia or Lithuania, while Piłsudski chased Tukhachevsky out of Poland and Belarus. As Zimmerman writes, ‘not only Poland but the Western world breathed a sigh of relief.’ Piłsudski was hailed as the saviour of Christian civilisation, though Lenin had had no clear plan for the offensive to sweep on and carry the revolution across Europe. The left in Europe took a different view. London dockers refused to load the ship Jolly George with munitions for Poland, and the Labour Party drove Britain to the verge of a general strike over it (until recently, Piłsudski’s name was mud in elderly British trade union circles). Zimmerman makes no mention of this, though his account of the battle itself is rich and helped by eloquent maps.

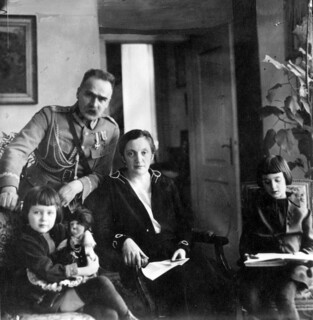

Piłsudski’s third problem was the constitution. He had handed over power to the reconvened parliament, the Sejm, so that it could promptly be handed back to him as head of state, though retaining sovereignty. No government could be appointed without its consent. Piłsudski was sincere in his hope for a Western-style parliamentary democracy. But this arrangement set the scene for a bad-tempered and eventually violent power struggle with the Sejm which lasted for seven years. He schemed to keep the National Democrats out of power via parliamentary combinations of centre-left and ethnic minority parties. Dmowski’s backers – the right-wing press above all – responded with campaigns of racial and antisemitic abuse, rising to a screaming climax in 1922 when Gabriel Narutowicz (not himself Jewish) was elected president with the help of ‘minority’ votes in the Sejm. On 16 December, Narutowicz was shot dead by a young fanatic who was instantly declared a patriotic martyr by the ultra-right. Piłsudski was exasperated by what he called ‘a stinking atmosphere full of venom and meanness’, and the murder appalled him. The following year he retired with his family to his country house at Sulejówek, near Warsaw. From there, prefiguring de Gaulle’s retreat to Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, he continued to overshadow and manipulate politics without holding office.

But, like de Gaulle in 1958, Piłsudski was eventually sucked out of retirement by his own sense of personal mission. Back he came in 1926, provoked by a government he hated which was bungling an economic crisis. On 12 May, at the head of loyal army units, he marched from Sulejówek to Warsaw. There followed a Shakespearean scene. Halfway across the bridge over the Vistula, Piłsudski was confronted by the president of the republic, his old comrade Stanisław Wojciechowski, backed by a few soldiers. Piłsudski told him to sack the government and get out of his way. To his astonishment, Wojciechowski flatly refused to do either. Lost for words, the commandant retreated to the other end of the bridge, and shortly afterwards shooting broke out. Two days of cruel fighting across central Warsaw ended in Piłsudski’s victory, at the cost of 215 dead soldiers and 164 civilian lives. The president and the prime minister resigned, leaving Piłsudski to appoint a new non-party government with himself as minister of war.

Piłsudski never quite recovered from what he had done. Neither did Poland. A crippled parliamentary system survived, but the ruling regime, the Sanacja (‘healing’), was increasingly composed of old Piłsudski buddies of an authoritarian mindset. Most Poles at first probably sympathised with the coup d’état, which had triumphed partly because the PPS and the trade unions had supported it with strikes. But politics soon turned septic. The new regime’s Non-Party Bloc for Support of the Government swamped elections, driving the non-communist left to unite in an alliance known as Centrolew. Huge rallies demanded the liquidation of the ‘hidden dictatorship’, until in September 1930 Piłsudski lost his self-control and ordered the immediate arrest of 11 Centrolew leaders. By October, the political prisoners in the military jail at Brześć and elsewhere numbered thousands, including 84 members of the Sejm and Senate.

The dictatorship was no longer hidden. But by now democracy was in trouble all over Europe, and when Hitler came to power in January 1933, the threat to Poland was obvious. Zimmerman, whose account of foreign policy in this period is detailed and careful, believes on the balance of evidence that Piłsudski did indeed, early in 1933, propose to France a joint pre-emptive attack on Germany before Nazi rearmament could get going. But France, once Poland’s firmest military ally, had other plans: a Four-Power Pact that would include Britain, Nazi Germany and Italy but had no place for Poland. Piłsudski fell back on an unconvincing ‘policy of equilibrium’, balanced on pacts with both Hitler and Stalin, whose insincerity must have been blatantly obvious to him. But he was ill now, and increasingly reliant on his foreign minister, Józef Beck, a right-wing disciplinarian who pulled Poland out of the Minorities Treaty and began to tilt the equilibrium towards Germany. After the murder of the interior minister by Ukrainian nationalists, a concentration camp for the regime’s political enemies was set up at Bereza Kartuska – harsh and sadistic, if not on the murderous level of Dachau.

Piłsudski died on 12 May 1935. The deluge followed, in stages. The Sanacja introduced or allowed shameful antisemitic rules, including ‘ghetto benches’ at universities, and pressed for mass Jewish emigration. Poland took advantage of Czechoslovakia’s fate after Munich to annex the Teschen/Cieszyn region in Silesia. But everyone knew that Poland was next on Hitler’s list. In August 1939, the secret clauses of the Nazi-Soviet Pact arranged for the abolition of the Polish state and a fourth partition between Germany and Soviet Russia. On 1 September, Germany invaded Poland. On 17 September, the Red Army invaded from the east. A tide of soldiers and civilians escaped through Romania to France, where the Sanacja disintegrated. Władysław Sikorski, a veteran of the Legions who had turned against the commandant after the 1926 coup, set up a new Polish state-in-exile, which moved to Britain in 1940. There Sikorski treated senior Piłsudskian officers as potentially disloyal, and interned many of them on the Isle of Bute; forbidden to take part in the war, they shuffled up and down the Rothesay esplanade in the rain, or gathered in the Italian café to exchange memories of their chief.

Assessing Piłsudski’s achievement involves a lot of counterfactuals – a way of saying that his leadership was lucky as well as brilliant. Would there have been an independent Poland if the partition empires hadn’t quarrelled and then collapsed – if there hadn’t been a First World War? Pretty certainly yes, given the growing tidal pull of nationalisms, but not in Piłsudski’s lifetime. Given that war and its outcome, would Poland have won its independence without his leadership? Yes, but a much smaller and weaker Poland, liable to fall under German influence even before Hitler came to power and politically so divided as to be almost ungovernable.

Piłsudski himself was the catalyst. His impatient, relentless purpose burned through empires and post-empire chaos. His best remembered words are: ‘To be defeated – and not to give in – is victory!’ Plenty of small boys dreamed of riding into cheering cities on a white horse (Piłsudski’s beloved mare Kasztanka was chestnut). Not many grew up retaining such self-belief. He had times of black depression, but anger – rage against the Russian occupiers, above all – never failed to revive him. Perhaps the secret was the unlikely mixture of ideologies he set out with as a boy: sabre in one hand, machine gun in the other. Antique aristocratic patriotism somehow fused with the socialism that grabbed him in his teens. His grief and outrage in 1886, when the Russians hanged four strike leaders from the Polish Proletariat movement, confirmed his belief that only independence could clear the way to a social revolution. But the socialism dropped away in the years ahead: ‘I took the red tram of socialism to the stop called Independence, and that is where I got off.’ Piłsudski ended as a lonely autocrat, so obsessed with his own achievement that he came to confuse himself with the nation he had freed. Disobedience to his will felt like treachery to Poland.

Like his subject, Zimmerman takes little account of the economy. This is a pity. Without some sense of the mammoth task of constructing a national economy out of the three partitions (different legal, educational, fiscal and transport systems; gross contrasts between rural backwardness in the borderlands and rapid industrial development in the ex-Prussian west), the impulses behind reckless party politics are harder to gauge. Piłsudski’s worst failure, ironically, was not in land reform or currency stabilisation but in modernising and equipping his beloved army. When the Wehrmacht attacked in 1939, 2600 German tanks advanced on about eight hundred Polish tanks and two thousand modern Luftwaffe aircraft took off against fewer than six hundred Polish aircraft. Devoted to his ‘boys’, Piłsudski thought they were a match for any foreign army. But that was true only of their courage.

In power, Piłsudski worried about the moral distortion inflicted on Poles by the partition century – and on him as well. Several historians have written that he was too much of a conspirator to make a good statesman. Zimmerman says cautiously that he had ‘a singular vision for a democratic, pluralist state … but when faced with political crisis, his vision failed him.’ His experience – national humiliation, resistance, prison, exile, liberation – was that of Polish generations before and after him. And not only Polish. As a young officer, Charles de Gaulle had been a member of the French military mission advising Piłsudski during the Polish-Soviet war of 1920. In 1967 he visited Poland again, and I was standing next to him when he was shown round the Wawel cathedral in Kraków. We approached a certain slab in the floor. A communist official tried to stand in front of it, waving the guest to move past. But he stopped. Expressionless, he looked down from his height at the marshal’s tomb and spoke four words: ‘J’ai connu cet homme!’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.