Was the course of 20th-century British painting set when Walter Sickert decided he didn’t like standing out in the cold? His first biographer (and former student), Robert Emmons, insisted that ‘SICKERT IS ONE OF THE IMPRESSIONISTS’ on the grounds that, though not an original member, he was ‘so closely allied to them both in method and sentiment, as to take his place, naturally and inevitably, within the innermost circle of the school’. However, as Peter Campbell wrote in the LRB (3 February 2011), English painters ‘responded to Impressionism’s escape from the academic into the everyday, but made something tighter and darker of it. The French pleasure in picnics and river parties and weather wasn’t naturalised here.’ It wasn’t impossible to do proper Impressionism in England: the Impressionists themselves did it, Pissarro most brilliantly in unlikely places such as Upper Norwood. But this wasn’t the path taken by the most talented, most Frenchified and most influential British artist of his generation. If Impressionism became ‘tighter and darker’ in England, it was largely because of Sickert, the painter of music halls and of men and women behind lowered blinds and closed doors.

So, was it the cold? ‘If [the painter] lives in a northern climate,’ Sickert wrote in 1914, ‘and has no hankering for physical martyrdom, he, with the rest of his countrymen, will work indoors. The house, where man is born, and married, and dies, becomes his theatre, and the sun shines as well, if sometimes more indirectly, on the indoor as on the outdoor man.’ Sickert enjoyed making pronouncements – his most recent biographer, Matthew Sturgis, calls him ‘a man of strong opinions loosely held’ – and this one should be treated with some scepticism. A more significant factor keeping Sickert indoors was his temperament. A bit-part actor in his early youth, he practised a theatrical as well as an artistic bohemianism, and was drawn to the grimier aspects of urban life, cultivated in the rooms he rented as studios in working-class areas of London. No picnics for him. ‘Dirty, tumbledown Camden town, Charlie Peace, pubs and cabbage’, was Hugh Walpole’s description of Sickert’s studio when he visited in the 1920s. (Charlie Peace was a notorious Victorian criminal.) ‘London is spiffing!’ Sickert wrote after a period away. ‘Such evil racy little faces and such a comfortable feeling of a solid basis of beef and beer. O the whiff of leather and stout from the swing doors of the pubs! Why aren’t I Keats to sing them?’ It’s true that Sickert was not always an ‘indoor man’: during the seven years he lived in Dieppe he mainly painted its architecture, as he did in Venice, sometimes in the open air; later, he made chalk-bright paintings of Bath. But I suspect he would have argued that, whatever the subject, his best art possessed an indoor sensibility. ‘Have you never worked from nature?’ Victor Pasmore asked him in 1938. ‘Not since I was grown up,’ Sickert replied.

According to its catalogue, the Tate exhibition aims ‘to reintroduce Sickert to French audiences’ – the show’s next stop is the Petit Palais – and ‘to remind British audiences of the importance of French sources to his work and to the British artists he influenced’. The first ambition isn’t a criterion for selection, which presumably explains why the show is essentially a retrospective; the second is hardly achieved by either the exhibition or the catalogue. The quantity and quality of the work gathered is terrific, but a full understanding of Sickert’s development – what he might have meant by being ‘grown up’, and when that happened – is thwarted by its thematic organisation, which maintains a general forward momentum, but persistently muddles radically different works from different decades. In 1936, Sickert wrote a letter to the editor of the Daily Telegraph:

A paragraph in your art critic’s article on the National Portrait Gallery has met me like a refreshing breeze … ‘Clearness in arrangement should be the first consideration, and a chronological order is the simplest of all. Even if this were followed out with a certain ruthlessness, hanging large pictures beside small, and drawings beside oils, the gain would be worthwhile.’ Yes, chronology is the only reliable old nurse for our nurseries. All the rest is twaddle.

The curators of the Tate show should have been led by their subject. The first room is a pure piece of crowd-pleasing twaddle, filled with self-portraits from across Sickert’s career, some of them important works, that have been sundered from their natural bedfellows elsewhere. (More on this later.)

Sickert would not have been Sickert without two early mentors, Whistler and Degas. He was a 21-year-old dropout from the Slade in 1882 when he was introduced to Whistler at a party and became his dogsbody and apprentice, in an echo of the relationship between Burne-Jones and Rossetti, which began a few decades earlier. The following year, tasked with conveying Whistler’s painting of his mother to the Salon, Sickert met Degas for the first time (he also spoke to the dying Manet through a bedroom door, and visited his studio). From Whistler he learned to manage gradations and harmonies of low tones, using an extremely limited palette – sometimes one that was physically shared between them, with Sickert working on the same subject by Whistler’s side. At the Tate are two delicate examples of Sickert’s early work, both made at Dieppe in 1885, where he spent the summer in the company of Degas and Whistler (whose visits overlapped): a small painting of a boucherie in which the meat hanging outside shares the dull pink and grey-white tones of the doorframe and the road in the foreground; and a panel showing tourists on the beach, the tents and the sea related by a tinny blue, and the clouds created out of the colours of the sand and the women’s dresses. In these works, Sickert was deploying Whistler’s preferred alla prima, or ‘wet on wet’, technique, which Whistler also used for large-scale canvases. The paint wasn’t given the chance to dry between stages, but added cumulatively over a short period of time. It could work beautifully, but more often it didn’t. Whistler allowed only one in three of his canvases to survive: ‘I cannot remember how many of these I helped him to cut into ribbons on their stretchers,’ Sickert wrote.

Sickert realised that, despite his skill and knowledge of paint, Whistler’s dedication to the alla prima technique had confined him to a ‘very limited and subaltern position’. Degas urged the use of his own (traditional) method, which was to bring a painting about ‘by conscious stages, each so planned as to form a steady progression to a foreseen end’. His finished works were based on quantities of preliminary studies and on underdrawings, with time given for drying between each stage. This was as different from Whistler’s approach as it was from that of Degas’s fellow Impressionists, who remained committed to painting en plein air. Inevitably, it placed great emphasis on draughtsmanship – ‘always, always draw lines, lots of lines,’ was the instruction of Degas’s own mentor, Ingres. During that Dieppe summer of 1885, Degas made an observation that Sickert considered ‘of sufficient importance never to be forgotten’: ‘They [the other Impressionists] are all exploiting the possibilities of colour. And I am always begging them to exploit the possibilities of drawing. It is the richer field.’ It was his sense of these possibilities that allowed Degas to take the ‘painting of modern life’ indoors, and to restore the primacy of the human figure in his carefully composed pictures of laundresses, drinkers, bathers, café singers, orchestras, audiences, and, of course, dancers.

Sickert was primed to be receptive to advice that asserted the centrality of line. His Danish father made a living producing black and white illustrations for a German magazine (Sickert’s mother was English, and the family moved to England from Munich in 1868, when Sickert was eight). He already shared Degas’s admiration for Charles Keene, an illustrator for Punch whom he later described as ‘the greatest English artist of the 19th century’. His apprenticeship preparing Whistler’s etchings, and his experiments in the same field, must have further refined his draughtsmanship. It also seems likely that he was influenced by the ‘special artists’ who produced high-quality visual accounts of contemporary events for the illustrated newspapers in the 1880s and 1890s. Lance Calkin, Frank Craig, Samuel Begg, Paul Renouard and others filled the pages of the Illustrated London News, the Graphic and Black and White while continuing to exhibit at the Royal Academy and the Salon. Their newspaper work – its realism and variety of subjects, its experiments with cropping and composition – did not attract the criticism meted out to Sickert and others, but may have done as much to seed the lessons of modern art in Britain.

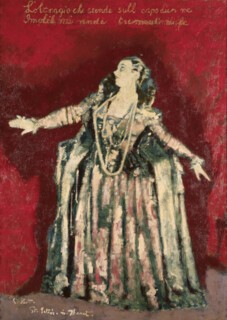

These early influences are apparent in Sickert’s music-hall interiors of the late 1880s and early 1890s. Whistler is there in the control of low tones: the effects of artificial light in near darkness are conveyed by deep reds (on plush curtains and performers’ dresses) that are alternately ashy and warmly glowing, as well as by the picked-out gilt of rails and mirror frames, the widening, thinning and belatedly concentrating projection of a spotlight and the mottling flames of gas chandeliers. Manet and Degas are there, most obviously, in the choice of subject and in the intelligence of the compositions: the actors viewed from the stalls, often with an intervening row of heads and often in reflection or in multiple reflections, creating complex and sometimes confounding perspectives. The brushwork is for the main part unobtrusive, the paint smooth (Degas advised proceeding as though painting a door).

Degas is also there in the centrality of line. Sickert spent night after night at the halls with his sketchbook – he was a genuine fan, given to singing or quoting old tunes in later life – and was clearly attracted by the late Victorian splendour of the decor as it combined with other, less static forms. The pictures break down into vertical and horizontal divisions created by stage-rails, mirror frames, curtains, hats, chairs, columns, walls, as well as the sweeping curves of the galleries and the flowing outlines of heads and figures. In Bonnet et claque, for example, the actress Ada Lundberg’s face is pressed close against the picture frame, in profile, cut off under the chin, her open mouth wobbling with vibrato; behind her head rise three rectangles, themselves subdivided by multiple gold lines, representing the embellished walls that enclose four goggling young men in hats. They form a dark pyramid that peaks in a lad whose hat brim is perfectly enclosed between two more vertical gold lines, to the left of which are two descending diagonals, representing part of a staircase. This infatuation with line is obvious, too, in Gallery of the Old Bedford, composed of two not quite connecting curves, one probably an ornamental lintel for a doorway, the other the gallery projecting beyond it, with a pile-up of men who seem to lean against a central column distinguished by two red vertical lines (repeated lower down by two horizontals in the same colour) and a background diagonal beginning with the audience member in the far-right corner (is he reflected in a mirror?) and continued by the men reflected in what is undoubtedly a mirror on the opposite wall.

There is a tendency to discuss these pictures as documentary. Thomas Kennedy writes in the Tate catalogue that Sickert is offering ‘realistic representations of people who visited music halls … His works show how people unconsciously engage with the social performative act of being part of an audience.’ But though the figures reveal the influence of Daumier, another of Sickert’s heroes, they are not especially individuated. Their purpose seems more formal. Sickert remembered examining with Degas a massive painting of a hundred strikers, each one of them carefully distinguished. ‘Yes! I have counted them,’ Degas said. ‘There are quite a hundred. But I don’t see the crowd. We make a crowd with five people and not with fifty.’ Sickert provided a gloss:

It is possible to depict the discomfort of a whole row of people by emphasising the discomfort of one. People or things that are in series, like Frith’s Derby Day, ought to go in portfolios or books. If you are among crowds, you must try to catch the concatenation of movements and so produce the kind of beauty that Indian filigree has.

Sickert, like Degas, was more concerned with tracing the new forms created by ‘modern life’ than with conveying social information. ‘For a painter like myself one place is as good as another,’ he said to the artist Jacques-Émile Blanche in 1920. ‘I tell you there are no subjects pictorial in themselves. It is the painter who makes use of them for his own ends.’

In his conversation with Blanche, Sickert went on to say that ‘Dieppe and Venice were convenient to me, that is all.’ The room at the Tate given over to paintings from the period of his life that included multiple visits to Venice (with two long stays in 1895-96 and 1903-4) and repeated summers in Dieppe, followed by a permanent move there in 1898, might prompt an uncharitable interpretation of this remark. The shift in focus was pragmatic. Sickert’s music-hall pictures had gained him some recognition and more notoriety, but they had not sold. Money was a concern, since he was getting divorced from his wealthy wife, Ellen Cobden, who had funded his existence (all those nights at the halls and away from home can’t have made her feel wanted). There was a bigger market for sunny Continental subjects. His views, as I said, were mainly architectural and some were painted outdoors: churches, hotels, harbours, other tourist destinations. They played to his strengths in line. The best, such as his paintings of the lion and horses of St Mark’s, are tightly cropped. Three large pictures of the basilica in different light have thrilling colouring in the top half, against the sky, but Sickert doesn’t seem to have been entirely sure what to do with the rest (presumably because in choosing the subject he was thinking more about prospective purchasers). During this period he also produced the interesting, semi-abstract self-portrait of 1896, with its short criss-crossed brushstrokes, as well as the wonderful picture of a tubercularly elongated Aubrey Beardsley, but at the Tate these are unhelpfully shown in two other rooms.

Nevertheless, there is a sense of drift. R.H. Wilenski, in his contribution to a catalogue published in 1943, wrote that Sickert ‘was a late, an astonishingly late, starter … If he had died at forty [in 1900] we should have to judge him today by the dainty Whistlerian pastiche, The Laundry (1885), some Whistlerian presentations of … St Mark’s’ and his other pictures of the music halls, Dieppe and Venice. Sickert himself would have seen the justice of this. ‘I am clear-sighted enough,’ he wrote to a friend in 1907, two years after he had returned to London from Dieppe,

to realise that the backward position I am in, for my age, and my talent, is partly my own fault. I have done too many slight sketches, and too few considered, elaborated works. Too much study for the sake of study, and too few resumes of the results of study. It is only just that the world will not keep a painter in comfort who works only for himself & does nothing for it.

Sickert could afford to be clear-sighted by this point because he knew that his art had changed and that he was making up ground. The work done during his period abroad might not have been his best, but it had sold, and he had begun to exhibit regularly in Paris (including his music-hall pictures, which had a better reception there than at home). His friendship with Degas had deepened. He had made a prolonged study of contemporary work – Monet, Renoir, Cézanne, Seurat, Signac, Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Matisse – and become friendly with Bonnard, Vuillard, Félix Fénéon and others. Most important was his exposure to Pissarro. Degas admired Pissarro more than any other of his peers, and Sickert spent time with the two men in 1900. The next year, Pissarro was in Dieppe during the summer, and Sickert sat down to watch him paint (as Cézanne had done thirty years before). According to Sturgis, ‘Pissarro offered him advice about his palette, urging him towards a further lightening of tone and purity of colour.’ When Sickert had a solo exhibition at Bernheim-Jeune in 1904, Blanche, in the introduction to the catalogue, linked his name with one other major painter besides Whistler and Degas: Pissarro. It is strange that so little is made of this connection by the Tate. Pissarro doesn’t even get a mention in the (otherwise superior) catalogues produced by Piano Nobile and the Walker Gallery to accompany their smaller Sickert exhibitions last year. Yet Emmons, in his 1941 biography, was insistent that Pissarro was fundamental to Sickert’s development. Sickert himself never lost an opportunity to state the significance of the ‘least assertive and truest painter’, whose importance, he wrote in 1911, ‘has not yet been properly understood’:

To study the work of Pissarro is to see that the best traditions were being quietly carried on by a man essentially painter and poet. For the dark and light chiaroscuro of the past was substituted a new prismatic chiaroscuro. An intensified observation of colour was called in, which enabled the painter to get the effect of light and shade without rendering the shadow so dark as to be undecorative.

In Pissarro’s work, Sickert noted elsewhere, ‘though exquisite places, or exquisite groups, are sometimes the excuse for the painting, the principal personage is the light.’ That ‘prismatic chiaroscuro’ – ‘prismatic’ is just right, with its suggestion of multiple planes – was created by what Sickert called the ‘innumerable gravity of [Pissaro’s] touches’, his massing and marshalling of colours to capture the many different densities of light and shade in a single scene. Discussing Pissarro’s Côte des Boeufs at L’Hermitage (1877), he wrote:

A writer of today is almost afraid to use of a work of art the term ‘laborious’. He would probably be supposed to imply deprecation … But the charm of a picture like this lies chiefly in its immense and indefatigable laboriousness, in labour so cunning, so swift and so patient, that the more it is piled up, the greater the clarity and simplicity of the result.

‘So swift and so patient’ and ‘the more it is piled up, the greater the clarity and simplicity’: these seeming paradoxes became central to Sickert’s practice. He was spurred on by friendships with the artist Spencer Gore and Pissarro’s London-based son Lucien, with whom he founded the Fitzroy Street Group in 1907 (this preceded the Camden Town Group, with considerable overlap of membership). He learned to establish the essential masses of colour in a picture before laying down paint in a wider range of colour, much more thickly, in distinct, deliberate strokes – sometimes small, ‘like postage stamps’ – not mixing them, but, like Pissarro, allowing them to vibrate chastely next to one another. The painting would dry and then he would return to it, making further ‘touches’. This process was repeated, layer after layer, ‘free loose coat on free loose coat’, until he was satisfied. Introducing a seeming paradox of his own, he referred to his ‘leisurely exhilarated contemplation’.

This change in style can be seen clearly in the contrasts between his new music-hall pictures and their predecessors. Sickert described the paintings of French halls as ‘real busters’, adding significantly that he had done ‘only red and blue places, instead of black’. In L’Eldorado, which shows the dress circle, the figures that would once have been like ‘filigree’ are now defined, as the light falls on their faces, with deliciously thick splodges of bright paint. The whole canvas is so densely worked that it bubbles. Even the pictures of British halls from the same period, though darker and superficially similar to past work, show a painter more focused on the challenge of treating light, of producing form from colour. In Noctes Ambrosianae, the faces and hands of the men up in the gods, lit from below, are seized out of the darkness by touches of flesh-pink paint, the gilt on the balcony with strips and dashes of gold.

The shift is evident in his other work too. In the Self-Portrait of 1907 Sickert’s head is contre-jour (against the light), and his features approximated from dirty pinks in mould-like patches on grey-green. Or consider Rue Notre Dame des Champs, a night-time street scene (unusual among Sickert’s paintings in being Parisian). The ground colour is a light purple. The architecture has been sketched in – a barber’s shop bulges in the foreground, its shape rendered by thick dark stripes. The street curves from the left to fill the back of the picture. But the real pleasure comes from the superimpositions: in the large areas of dark purple shadow in the foreground; the puddled turquoise, khaki greens, brownish golds and pale blues standing for the light cast by the shops, which are then picked up and striped down the buildings in the background to give them form; the blacks that suggest figures on the pavement; the lilac and blue blotched over the purple sky. And all this colour is somehow, obviously, a street in Paris at night.

At the Tate, these pictures from 1906 and 1907 are displayed in different rooms – the music-hall pictures with those done twenty years before, the self-portrait at the opening, the street scene with the pictures from Dieppe and Venice. Yet they are a vital context for the nudes he was painting at the same time, gathered in a separate, admittedly spectacular room. Sickert painted his first nude in Dieppe, and more in Venice, having been driven indoors by the rainy autumn and winter of 1903 (sometimes his dislike of bad weather was significant). In 1905, back in London, he started again, working out of rooms in Mornington Crescent, posing his female models on iron bedsteads usually in the light of a single window, surrounded by tokens of a rough domesticity: rug, chair, chamberpot. The women were not always conventionally attractive, or young; and they were viewed from unusual angles and posed in unusual positions. The ‘principal personage’ in each picture is the light: the light which runs up or across their bodies, catching on a knee or a breast or darting off the bed frame, and which wells darkly in and spills brightly over the deep creases of a sheet. ‘The object of illumination is to reveal form,’ Sickert said, and the human form was fundamental. Indeed, it seemed to him that ‘perhaps the chief source of pleasure in the aspect of a nude is that it is in the nature of a gleam – a gleam of light and warmth and life.’

In Nuit d’été (c.1906), we view a woman on a bed from across the room. She leans back, her right leg tucked under her at a right angle, the left hanging over the bed, foot resting on the floor. The light, falling from somewhere to our right, gilds the top of the outstretched leg just above the knee, falling on the thigh of the leg tucked beneath her, and up across her stomach and breast. The areas that remain in shadow are painted closely in pink, green and mauve, the torrid sheet in purple. Her face, also in shadow, is almost featureless – there are two broad strokes of mauve across her cheekbones, like sticking plasters. I can’t convey the subtlety of the colouring (nor can a reproduction). But I can insist on the delicacy and variety of the dipping brushstrokes, on how softened and edgeless everything is: a shadow swoons at the foot of the bed, which seems to sink into it. What Sickert was aiming for – and achieving – in these pictures is illustrated by an anecdote from one of his students, the writer Enid Bagnold. She brought home a nude done in Sickert’s style. Her father was scandalised. ‘Where’s the outline?’ he demanded. Bagnold replied in her teacher’s voice: ‘Stumbling and flashing with enthusiasm I tried to say – “You map the lights and shadows. You bounce the light off it. And if you manage it right, there sits the creature, living, in the middle. You don’t need an outline!”’

It’s a pity that the Tate reproduces so much of the contemporary British and French criticism of these works, which, though arriving at different conclusions (the British were repulsed; the French titillated), shared a set of assumptions: that all these naked women were prostitutes, that they were ugly or ill or both, and that they were being shown in the sordid, spoiled gloominess of their lives. ‘Monsieur Sickert observes figures dying in obscure rooms in London,’ the critic Gustave Geffroy wrote. It is impossible to stand in front of the same pictures today and not think this all rubbish. These are romantic paintings. Surrounded by so much soft rounded flesh, I was reminded of Renoir.

Sickert didn’t think of his work the way others did (which isn’t to say that he didn’t anticipate, and perhaps calculate on, their response). He liked his models, liked chatting and joking with them, and paid them well. It appears that they liked him. (Max Beerbohm once made a note on Sickert’s character which began: ‘His charm – for all women – duchess or model’.) You feel it in the pictures: there is dignity in those relaxed, disregarding, ‘undignified’ poses. Sickert was an energetic and plain-minded sensualist, in whose mind art and sexuality mingled easily: in 1899, he complained to William Rothenstein that there was nobody in Dieppe ‘to talk art and fucking with’; after a period spent etching, he reported that its constraints were making him ‘letch for the brush’. He liked dirty old London and his dirty rooms. ‘He loved dust,’ Bagnold remembered. ‘Especially dust on mirrors. He loved the abated light that got muffled on the glass. “Blonde,” he would mutter. It was a love-word.’

Even the provocatively named ‘Camden Town Murder Series’ – pictures of naked women on beds with clothed men sitting or standing by them – fails to live up to the billing. Unsurprisingly, since most of the paintings had other, non-murder-related titles at various points. (Sickert, in poor taste, appended most of the titles as a publicity stunt after the murder of Emily Dimmock in Camden Town in 1907.) We are instructed by the exhibition captions to see incipient violence and menace, but I could see only the way the light travels in pinks across the woman’s body in What Shall We Do for the Rent?, before bolstering in thick white highlights on the shirtsleeves of the man who sits beside her; or the way it is evoked in the vigorously combined blue-white-grey-pink at the bottom of the bed in L’Affaire de Camden Town, in the red-brown hatched brushstrokes on the woman’s shin and breasts, and the way the white shirtsleeve of the man looking down at her becomes duck-egg blue in the shadow, his face terracotta. Look closely at Dawn, Camden Town (sometimes known as Summer in Naples) and you see that the woman is smiling – Sickert has painted in chirpy little teeth.

These pictures were Sickert’s greatest successes in France. By 1910, according to Delphine Lévy, his collectors included Gide, Daniel Halévy, Fénéon, Bonnard, Pissarro and Maximilien Luce. Authorised by Signac to purchase him something from Sickert’s show at Bernheim Jeune in 1909, Fénéon chose L’Affaire de Camden Town. It was also, though it was not obvious at the time, the beginning of the long upswing in Sickert’s reputation at home, as he took a paternal role in the Camden Town Group and produced more pictures of male and female couples in charged proximity, usually both clothed, with names like Ennui and Off to the Pub. And it was around this time that Sickert began referring to himself as a ‘literary painter’, continuing to do so for the rest of his life.

Yet when discussing picture titles, rather disingenuously in light of his own opportunistic behaviour, he could thunder that ‘IF THE SUBJECT OF A PICTURE COULD BE STATED IN WORDS, THERE HAD BEEN NO NEED TO PAINT IT.’ What, then, did he mean by calling himself ‘literary’? In 1912, he explained that

it is just about a quarter of a century ago, since I ranged myself, to my own satisfaction, definitively against the Whistlerian anti-literary theory of drawing. All the greatest draughtsmen tell a story. When people, who care about art, criticise the anecdotic ‘picture of the year’, the essence of our criticism is that the story is a poor one, poor in structure or poor as drama, poor as psychology … [But] a painter may tell his story like Balzac … He may tell it with ruthless impartiality, he may pack it tight with suggestion and refreshment.

I quoted Sickert earlier as saying that ‘there are no subjects pictorial in themselves.’ Duncan Grant recorded with some puzzlement that Sickert had ‘a belief in subject in spite of repeatedly saying one subject is the same as another’. What he meant is obvious enough, though. He was insisting – in opposition to Whistler’s aestheticism, his ‘wet on wet’ immediacy, his pictures’ flat depths and flat mixed colours – on painting not as surface beauty, but as a set of considered formal relationships that exist in space and generate meaning. In 1926, by which time he had been elected to the Royal Academy, he grabbed a student by his lapels and told him:

You and I are going to have a talk on superficiality. My colleagues at the academy think that finish means smooth neat paint. Don’t believe them. Finish consists in relating the figures and objects, the one to the other and to their setting. You must be able to walk about in a picture. It should give you the sensation of something exciting happening, taking place in a box as it were, only the front of the box has been taken away so that you may look inside.

When Pasmore asked Sickert if he had ever worked from nature, and received that reply, ‘Not since I was grown up,’ Clive Bell, who was present, interjected that he happened to know that Sickert had worked from nature in Venice. The assumption was that Sickert must have been ‘grown up’ by the late 1890s and was fibbing (Bell and Roger Fry both took a schoolmasterly tone with Sickert, who would not quite fall in with their conception of things). But perhaps Sickert did know what he was talking about. While he may have decided post facto that he became ‘literary’ in opposition to Whistler as early as the 1880s, his sense of purpose and identity seems to have clarified in the early 1900s. When he said that ‘in painting, as in literature, conception should have something of an inevitable flash, and execution a certain concision that by no means excludes laboriousness,’ it can’t be a coincidence that he was evoking the qualities of ‘laboriousness’ and ‘simplicity’, as well as the ability to locate the hour of the day that ‘brings out with [most] significance the character of the object illuminated’ – the things he praised in Pissarro. What he had learned was how to pull the constituent parts of a picture into tension, with light as the unifying factor. He understood now that he was, with his ‘leisurely exhilarated contemplation’ and his patient, deliberate laying on of paint, a ‘literary’ creator. Urging his friend Ethel Sands to practise this technique, he described it in revealing terms: ‘One day something happens, touches seem to “take”, the deaf canvas listens, your words flow and you have done something.’*

In the 1920s, sceptical of the rush on Cézanne, harassed by modernists such as Jacob Epstein and Wyndham Lewis, and bereaved by the premature death of his second wife, Sickert seemed in danger of falling from the artistic front rank and into the consolations of life as a character, or rather – since he was always that – as only a character. He became maniacal about taxis, taking them everywhere and leaving them running for hours outside the places he visited. He began to send expensive telegrams rather than letters. He sold paintings in large batches, stupidly cheap, on the condition that the buyer could not see what they were buying (they would be stacked face-forward against the wall). His love of dressing up intensified. One day he might appear as a country squire, the next as Bill Sykes, with a rowdy red neckerchief and a hat slouched over one eye. He grew beards in eccentric shapes, and sometimes shaved his head. Then, in 1924, he announced that he wished to be called by his middle name, Richard (possibly in order to have ‘Dicsic’ as his telegraphic address). ‘He’s almost entirely occupied with himself and his effect,’ Fry grumbled. ‘It’s surprising with such a temperament he’s so good an artist.’

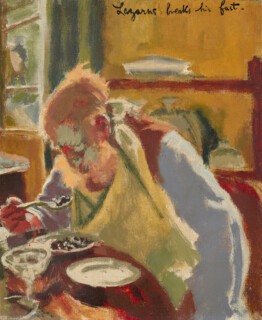

The paintings still came. The Tate separates by many rooms his portrait of Victor Lecourt (1921-24) and Lazarus Breaks His Fast (c.1927), the self-portrait he made after his recovery from serious illness (possibly a stroke), but they are united by the bright flossy orange that infuses Lecourt’s beard and burnishes his side, and which constitutes the ageing Sickert’s hair and beard, pouring down his napkin as he sits eating from a bowl of berries in front of a window. This second painting is magnificent. Sickert took the composition from a monochrome photograph (the Tate includes it), changing the depths – in the painting, Sickert’s figure takes up far more space – and recreating the simplified tonal contrasts in colour. Surrounded by that bright orange, the shadowed face is made up of layered red, brown, orange, muddy green, with a brighter green in large patches over the top. White swirls round the plate and bowl and the rim of the glass, driven up the spoon that is on its way to his mouth.

Sickert had used photographs to assist with his compositions since the 1890s, but it was only now that he began to make them the basis for paintings, a ready-made tonal guide on which he could freely elaborate. By the late 1920s, he increasingly painted from photographs he found in the newspapers: George V and Queen Mary, glimpsed through their carriage windows, in warm pink and coral against a white background; the crowd gathered to greet Amelia Earhart when she landed in London, white rain slashing and dripping across the blueish canvas; a striking miner fiercely kissing his wife, an equally fierce red sparking up her profile. At the same time, he was also producing what he called ‘echoes’, new versions of compositions rooted out from copies of the Victorian illustrated papers he’d admired in his youth, enlivened by jabs of 20th-century colouring.

These late developments can in part be put down to Sickert’s age and restricted mobility, an inability or unwillingness to hunt out new models and subjects in the city. They might also be seen as his return to line, or more specifically, in the case of the paintings, outline – his response to a new mass media age, in which people were forever shedding spectral visual skins in the form of photographs or film. His two portraits of the actress Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies are fascinating for the decision to foreground the mediated nature of the primary image. In one we are given the photographer’s trademark at the bottom of the canvas; in both she is rendered in black and white (except it isn’t actually black and white, but black and white and green and red) against a coloured backdrop, like a figure that has flickered off the screen into real life.

Alternatively, these paintings and the ‘echoes’ might represent Sickert’s ultimate escape from line – the borrowed compositions were often drawn onto canvas by assistants, or by his third wife, the artist Thérèse Lessore – and his final floating free into colour, now his sole preoccupation. Neither interpretation satisfies. Sickert, with his usual restlessness, had simply arrived at a new combination. It was his own version of modernism and the final achievement in an astonishingly energetic and individual career. Before his death in 1942, he skittered away into a cheerful senility, though he had been acting parts for so many years that some of his friends couldn’t decide whether or not he was having them on. Visiting him on his 79th birthday, Rothenstein thought he was playing ‘the centenarian beautifully’, forgetting his teeth and bumping down the garden steps on his arse. Still Sickert painted, almost to the end. ‘There is no absolute reason why we shouldn’t learn something,’ he had said in 1932, ‘although we are grown up.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.