‘Carte de visite’ was a misnomer from the beginning. No one, it seems, ever left their photograph, mounted on a card about 4.5 x 2.5 inches in size, as proof that they had paid a call. People were too enthralled by this new technology to treat it so casually, and although cartes were relatively cheap, they were too costly to be sacrificed so blithely. Instead, photos were given to friends and family, received in return and put in albums that, with their worked leather and clasps, looked a little like family Bibles. People had themselves photographed again and again, by a different photographer, in a new outfit or with a new haircut or a new beard or a new shave, with a new husband or a new wife or a new baby, against a new backdrop, with new props. As well as possessing pictures of themselves and the people they knew, they were soon buying likenesses of the rich, famous, powerful or notorious. The association of the phrase ‘carte de visite’ with a fleeting or missed meeting is inappropriate for this omnipresent phenomenon, one that produced decisive social and cultural change. Paul Frecker provides abundant proof of the ‘Cartomania’ that seized Britain in the 1860s, although, as he admits in a winning footnote, there is no evidence that this term was ever used by anybody Victorian.

Cartes were the products of multi-lensed cameras that were able to make several exposures on one plate, producing up to ten different images per negative; once ‘printed onto light-sensitised, albumenised paper … these prints could then be cut up and pasted onto individual card mounts.’ A client would visit a photographer’s studio, pay a set price (ranging from shillings to guineas) and a few days later receive a packet containing their cartes. They were portable, swappable and could be popped in the post. The negatives were kept by the studio, so that the photos could be re-ordered. And if the sitter was famous, and willing – as they almost always were – the photos could (after protection was granted in 1862) be copyrighted, mass-produced, distributed to wholesalers and made available all over the world.

The general principle of the carte had been knocking around for most of the 1850s, but Frecker credits the French photographer A.A.E. Disdéri with initiating the boom with his photographs of Napoleon III, Empress Eugénie and the three-year-old prince imperial in 1859. In Britain, Queen Victoria and her large family were close behind. But it was ordinary people who bought these cartes in their tens of thousands, and who began to file into the studios themselves. It was ordinary people, too, in the main, who turned photographer to take advantage of the demand. By 1862, there were 35 studios on Regent Street alone. ‘When a man has failed in his own business it is said that he becomes either a schoolmaster or coal agent,’ John E. Cussans wrote in 1865: ‘to these may be added photographic art.’ After ten minutes’ instruction, anyone could ‘take a photograph of some sort’, and ‘twenty pounds will frequently suffice to set up a studio, including apparatus for small positives and cartes, and perhaps the plant and goodwill of an eel-pie shop attached.’

The mention of the eel-pie shop wasn’t just a jibe. Frecker shows that many photographers in the 1860s had other jobs and worked out of existing premises, some of them more obviously suitable than others: they were tobacconists, confectioners, booksellers, hairdressers, organists, vestry clerks, dyers, house-painters, sign-carvers and frame-makers, shoemakers and plumbers. There are examples of women running studios, sometimes with husbands, but also on their own or helped by their daughters. At the other end of the scale were the princes of the trade, many of them European but based or operating in Britain: Disdéri, Silvy, Sarony, Mayall, Elliott and Fry. Sarony’s studio in Scarborough, then a fashionable resort, had ‘as many as 98 rooms’ done up in Louis XV style and employed more than a hundred people. Together, the eel-pie lot and the princes were producing a staggering number of images: individual studios in smaller provincial cities such as Norwich and Bath reported selling between fifty and sixty thousand cartes a year. It has been estimated that as many as four hundred million cartes were sold annually in Britain between 1861 and 1867. The craze had faltered by the end of the decade: in 1869 the author Andrew Wynter claimed that ‘the demand at present is nothing like what it was,’ estimating an annual sale of only sixteen to eighteen million. The carte continued to be produced into the next century, but people began to prefer larger formats, with the option of putting their photos in frames, as well as in albums. By the 1880s, photos could be successfully reproduced in newspapers and magazines, reducing the need to buy likenesses of famous people. Most of the princes did well out of the glory years. Disdéri died destitute, but Joseph John Elliott left an estate worth £67,000.

We are so used to being photographed, at all times of day, in every stage and aspect of life, that it’s hard to imagine what it would be like to have your picture taken for the first time. The apparent sombreness of most Victorian sitters has fostered many modern myths, the most common being that their expression is a product of long exposure times, which required people to remain tense and still. In fact, exposure times were already short by the 1860s, especially if the light was good, and later in the century almost instantaneous. Victorians kept their mouths shut largely because the conventions of portrait photography were those of the painted portrait: you didn’t smile for Reynolds, so you didn’t smile for Silvy. (Sometimes people did. We even have a photo of Queen Victoria grinning, though she didn’t know she was being snapped.) No doubt people felt some strain – anyone who has had their photo taken by a professional and wondered how to organise their face and where to hang their hands can imagine themselves this far into the experience. In 1862, one widely syndicated article declared that ‘there are few periods of a peaceable man’s life more deserving the name of un mauvais quart d’heure’:

Of itself the attempt to select your own best expression of countenance is a perplexing effort, and the consciousness that the face you put on, whatever it may be, will be the one by which, in all future time, all who look into your friends’ albums will know you, does not diminish the embarrassment. You have a vague impression that to look smiling is ridiculous and to look solemn is still more so. You desire to look intelligent, but you are hampered by a fear of looking sly. You wish to look as if you were not sitting for your picture; but the effort to do so fills your mind more completely with the melancholy consciousness that you are. All these conflicting feelings pressing upon your mind at the critical moment are very painful; but they are terribly aggravated by the well-meant interposition of the photographer.

The snarling Saturday Review, true to form, complained of being ‘treated by a smirking fifth-rate artist for half an hour as something between a convict and a baby’. Photographers could be equally impatient. A Philadelphia practitioner observed that ‘some people have naturally a very bad expression; not unfrequently it is positively hideous,’ while others have ‘no expression at all, no more than the back of a spoon’. He added that sitters ‘think they are doing the fine thing, just when they are making themselves most ridiculous’.

Much advice was doled out to both parties. To get the best out of their subjects, photographers should be courteous and gentlemanly, cheerful, quick, unfussy, informal, confident. To get the best out of their photographer, sitters were recommended to book appointments early in the day, ‘before he has met with some nervous, restless sitter or spoiled child’. To get the best behaviour from their child, parents should ‘avoid giving or mentioning sweets’. There was also the perennial problem of what to wear, made more complicated by the demands of the camera. ‘In dressing,’ the photographer David Welch advised,

remember that in photography, blue is light, and red or orange is dark; and therefore, the more blue anything contains, the lighter it will be, and the more red or orange anything contains, the darker it will be … Another thing to be particularly observed is that whatever reflects back light comes out white, such as the polish on boots, the gloss on silks, oil in the hair, &c, hence black hair with much oil will come out as if grey.

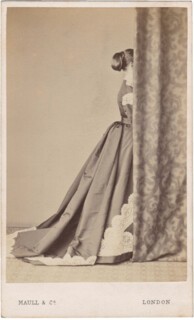

‘LADIES are informed that dark silks and satins are best for dresses,’ John Mayall wrote. ‘Shot silk, checked, striped, or figured materials are good, provided they be not too light … The only dark material unsuited is black velvet. For GENTLEMEN, black, figured, check, plaid, or other fancy vests and neckerchiefs are preferable to white.’ Got it? Some women arrived at the studios not yet wearing their outfits and required assistance in dressing from female attendants.

Then there were the poses to consider: standing, sitting, left or right profile, what to do with the stomach, elbows, hands and legs. ‘It constantly occurs that persons will come into the reception-room,’ Henry Peach Robinson wrote in 1868, ‘and selecting a portrait of another totally unlike in age, style and appearance, will say: “There, take me like that.”’ On the contrary, Disdéri reported that most sitters arrived with a pose, having tried several out in the mirror at home. He agreed with Robinson that they were clueless. ‘If you make the slightest fault by giving an unlucky turn to the knee,’ he pronounced, ‘or by placing the foot in a bad position, you destroy the whole logic of the position. Nothing is easier in such a portrait than to fall into awkwardness, without resemblance, or even into ugliness.’ Frecker thinks that Silvy ‘must have physically handled the majority of his sitters into the precise … attitudes of languid haughtiness, mannered elegance and exaggerated, contrapposto nonchalance which characterised his studio’s output, tilting each head to the desired angle, moving a hand here and turning a foot there, adjusting an arm or even a finger’. This would explain why he was known ostentatiously to don a new pair of white gloves for each appointment, casting the used pair into a brimming basket. And yet for all his finicking Silvy was an extremely productive man. His daybooks show that he accepted as many as 34 sittings a day, which Frecker calculates as meaning that on average they would have lasted no more than twelve minutes.

In 1862, Wynter visited Silvy’s West End studio for Once a Week, providing a glimpse of the many hands on which his art, efficiency and profits depended.

One room is found to be full of clerks keeping the books, for at the West End credit must be given; in another a score of employees are printing from the negative. A large building has been erected for the purpose in the back garden. In a third room are all the chemicals for preparing the plates; and again in another we see a heap of crucibles glittering with silver. All the clippings of the photographs are here reduced by fire, and the silver upon them is thus recovered. One large apartment is appropriated to baths in which the cartes de visite are immersed, and a feminine clatter of tongues directs us to the room in which [they] are finally corded and packed up … [Silvy’s subordinates] have set afloat in the world 700,000 portraits from this studio alone.

The carte did not long limit itself to the studio portrait – the commercial market demanded views of all sorts – and the life of the out-of-doors photographer was far more haphazard. One photographer, who had the byline ‘A Rambler’, wrote in 1866 that

there are some men who get good pictures without a crowd of stupid gazers staring at the lens. I wonder how they manage it? I can never put my camera at the corner of a street or lane, but, if nobody was to be seen about for the last quarter of an hour, they all manage to turn out then. The men and women are bad enough, but oh the boys! – oh the boys!

Frecker includes a photo of a statue of Queen Victoria in Aberdeen, surrounded by a crowd of boys, most of them sufficiently roisterous to have become blurs. The challenges were greater abroad: ‘The commonest vexations involved extremes of temperature, copious quantities of sand and dust which adhered to the sticky collodion, and often the absence of a ready supply of water for washing the glass plate negatives.’ (Working out of a ramshackle van during the boiling Crimean summer in 1855, Roger Fenton found that the corks kept shooting out of his bottles of chemicals, and that he couldn’t take pictures after 10 a.m. That was before you factored in the war.) There could be dangers to life. William Moens, a gentleman photographer travelling in southern Italy in 1865, was kidnapped by brigands along with his clergyman companion. One man was to be set free to raise the alarm and the ransom, and the two friends drew straws. Moens lingered in captivity for 102 days before paying £5100 for his freedom. When he shortly thereafter produced his two-volume English Travellers and Italian Brigands: A Narrative of Capture and Captivity, the Pall Mall Gazette hoped the brigands’ next victim would be ‘a gentleman of greater literary ability’.

The carte de visite made the world visible to itself. Its effect was as radical as film or television or the internet. Anybody and anything could be photographed, and the photograph could travel anywhere. The carte broke down and remade hierarchies, effectively inventing modern celebrity. Cartes replaced prints in shop windows and passers-by goggled at displays that promiscuously mixed types of distinction, squeezing ballet dancers next to bishops. Max Beerbohm remembered going as a child to inspect the London Stereoscopic Company’s ‘great long double window on the eastern side of Regent Street’ and realising for the first time that his political heroes, read about in the papers and cartooned in Punch, existed as real people, ‘tailored and hosier’d as men’. What was on offer was a new kind of physical and imaginative intimacy with distant lives. As the historian John Plunkett writes, cartes were ‘literally touchy-feely artefacts – not to be framed and looked at with deferential awe … but catalogued and collected, gossiped and commented upon. By the very literal handyness of their use [they] imbued their subjects with the quotidian qualities of their format.’

It’s unsurprising that monarchy was there at the start of the phenomenon: it has always been invested in propagating its image, and the revelation of the royals’ genuine appearance – they were almost always depicted wearing ‘bourgeois’ clothing and often at symbolic moments shared with their subjects: marriages, births and deaths – provided the greatest celebrity frisson of all. It was so unexpected of Queen Victoria to decide in late 1862 to make available for purchase images of herself and her children grieving for Prince Albert (gazing at his bust, wreathing it in flowers etc) that at least one writer in the Photographic News was convinced they were fake:

It is quite lamentable that any one should believe these fancy pictures to be photographs from life, or real scenes: yet we doubt not that they are generally so accepted. People are actually so ignorant as to suppose that her Majesty, who has withdrawn herself from public life ever since her great affliction, would have permitted a photographer, for his trading purposes, thus to invade the very privacy of her grief. The manufacture of these photographic impressions says little for the honesty of those who produce them; and it also suggests the existence of a great deal of bad taste in the English public.

There was more outrage when cartes appeared showing the Prince of Wales with his hand on the shoulder of his fiancée, Alexandra of Denmark, before their wedding. But the public lapped it up. A charmingly informal photo of the Princess of Wales, as she had then become, with her baby daughter slung on her back, was the biggest seller of the decade.

‘Whatever seized the public’s attention, no matter how briefly, was immediately photographed in the new format,’ Frecker writes. In ‘an age when photojournalism was only in its infancy, the carte de visite was often the next best thing to frontline reportage,’ and acted simultaneously to ‘fan the flames of a subject’s fame or notoriety’. Empowered by the archival digital revolution, which has made hundreds of Victorian newspapers searchable at the click of a keyword, and deploying his own enormous collection of cartes de visite (he has been a collector and dealer for twenty years), Frecker is able to put together word and image to demonstrate how this process worked.

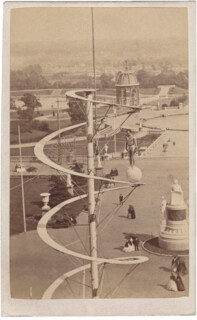

One chapter takes in the enormous excitement generated by the arrival of Japanese ambassadors, the Persian shah and the Ottoman sultan, as well as by legendary acrobats including Jules Léotard, the gender-swapping El Niño Farini and Charles Blondin, who performed to hundreds of thousands of people during a four-month residency at the Crystal Palace in 1861, crossing a tightrope while pushing his daughter Adele in a wheelbarrow, or ‘carrying his manager Harry Colcord on his back’, sometimes performing ‘blindfolded and sometimes turning somersaults. He also made crossings on stilts, on a bicycle and with his feet in buckets. One stunt involved stopping halfway over to cook an omelette on a bulky metal stove.’ Frecker provides an extraordinary elevated photograph of Blondin’s successor at the Crystal Palace, Signor Ethardo (Stephen Etheridge), in action. His act consisted in ascending ‘a spiral column fifty feet high [balancing] on a globe, and descending backwards’. In each case, dawning fame immediately created the demand for photographs (often taken in multiple locations and by multiple photographers), a rush to copyright and large sales, usually followed by eclipse once the craze was over.

We are given a new view – an even grubbier one – of the touring and exploitation of ‘exotics’ such as Tom Thumb and his equally diminutive wife, Lavinia (their marriage was genuine, but the children they later posed with were not their own); the ‘Aztec Children’ (microcephalic siblings with a mental age of two, who in a publicity stunt were married to each other and photographed in their wedding outfits); the eight-foot Chang Woo Gow; and the African-American conjoined twins Millie and Christine McCoy. A sidelight is thrown on Jumbo the elephant, whose glory had been taken for granted in his nearly two decades at the London Zoo before his arrival at a frenetic sexual maturity required his sale to P.T. Barnum’s circus. Amid public grief at his departure overseas and separation from his ‘little wife’, Alice the elephant, 43 photographs of him were registered for copyright over a short period in 1882.

The use of cartes as photojournalism surprised me. Cartes were sold showing the blood-soaked, bullet-holed waistcoat of Maximilian, emperor of Mexico, as well as his proud firing squad; the severed heads of Greek brigands; and mementos of the Paris siege (newspaper front pages, supposed menus offering rats and ostrich). Photos of Madame Tussaud’s wax models were passed off as genuine portraits, and two young girls who had been playing with Fanny Adams before her abduction and horrible murder were posed next to her headstone.

Cartes did not always straightforwardly serve their intended purpose. In a way that anticipates CCTV or Facebook or Google search, the studio photographer’s surveillance meant that individuals left a footprint by which they could be tracked, found and, potentially, publicised. As Frecker puts it, the ‘most unlikely figures could without warning command the attention of the press and public, thus filling the coffers of any photographer whom they might once have visited.’ He cites several instances when, after a scandal hit the press, photographers realised they had among their negatives images of its protagonists. They would then set about making public what had been private, often obscuring the fact that they had no permission to do so by describing the images in the most general terms in their applications for copyright at Stationers’ Hall. When in 1870 the cross-dressing artistes Fanny and Stella (Frederick Park and Ernest Boulton) were charged with public indecency and conspiracy to commit sodomy, Sarony of Scarborough and Fred Spalding of Chelmsford recalled that they had taken pictures of both, in and out of drag, along with their confrère Lord Arthur Pelham-Clinton, son of the duke of Newcastle. Spalding had made none of these photos publicly available before Park and Boulton’s arrest, but registered seventeen the next month. Their wide sale represents yet another example of the Victorians’ habit of eagerly discussing homosexuality while in the same breath enjoining silence. A writer for the London Figaro was distressed to find the pictures blatant in shop windows: ‘What has made these lads celebrated,’ he asked, ‘but a hideous suspicion which should not even be whispered? And their portraits are made attractions to the prurient-minded by traders whose “respectability” is undoubted, and who dare not tell their customers why the portraits are in demand. There is something to be ashamed of on each side of the counter.’

Another figure who could accidentally benefit the photographer, and potentially injure themselves, was the murderer. The likelihood of photographers profiteering from the crime of Edward Pritchard, a doctor in Glasgow who murdered his wife and mother-in-law in 1865, was greatly boosted by the fact that he was a pathological narcissist who had ordered more than five hundred cartes of himself from one studio alone (photos also went on sale of him with his wife, mother-in-law and children). Franz Müller, who committed the first murder carried out on a train in Britain – in 1864 Thomas Briggs was battered, robbed of his watch and chain, and thrown out of the carriage window – was followed to New York, overtaken by a detective on a faster ship and arrested on landing. Alexander Lamont Henderson had copyrighted and put on sale two photographs taken of Müller (one developed from a negative the sitter had rejected). A journalist for the Photographic News marvelled at the carte’s criminal-catching capacity:

It supplied the jeweller, who bought the plundered chain, with a means of identifying the foreign-looking person who sold it, and it rendered the officer of justice, who had never seen him, familiar with his features, so that he detected him amongst the crowd of passengers on the deck of the Victoria when on a fine summer day, it entered the bay of New York … There are few men … who have not at some time sat for a photograph, little dreaming of the weapon it placed in the hands of their pursuers should they at any time step into the paths of crime.

The police had already started using cartes as mugshots. Frecker has found a terrific one of a murderer called Charles Peace, who is gurning at the camera. This official image found its way to public sale a month before Peace’s execution, causing him to complain that it did not represent him truthfully. Apparently about ten months before his arrest he had ‘broke off a couple of teeth’; the ‘jagged stumps bothered him a good deal, and it was whilst working his jaws about to reduce the stumps to something like a level surface that he discovered he could so protrude his under jaw as to almost completely alter the expression of his face.’ When photographed by the police he had performed this trick in the hope of avoiding being identified, and gamely kept it up until he was charged.

Frecker also discusses cartes of courtesans, aristocratic runaways, scientists, clergymen and missionaries; landscapes and urban scenes at home and abroad; national types and peoples (the costumes of Newhaven fishwives and rural Welsh women, with their eccentrically tall hats, as well as Singaporean barbers, St Petersburg street-sellers and the ‘hidden women’ of Lima); and urban poverty (Barnardo’s was not alone in staging ‘before and after’ pictures of recovered street urchins). There is nothing, however, on actors, artists or writers (in 1931 Virginia Woolf, referring to that ‘bright and animated company of authors who … are known by their hats, not merely by their poems’, deemed that the ‘damage the art of photography has inflicted upon the art of literature has yet to be reckoned’). Other than four uncommented-on images of women in various states of undress, there is nothing on either sex or pornography, although this would surely have furthered the book’s implicit argument for the diverse oddness of 19th-century life, something many Victorians were happily aware of, and which prompted so much photography in the first place.

More useful still would have been a section on politics. Frecker notes that, if we measure by registered copyrights, Gladstone was the fourth most popular subject for cartes between 1862 and 1870, behind the Prince and Princess of Wales and Queen Victoria. Photos of Gladstone and other politicians played a significant role in the democratisation of Britain, allowing the governed to see their governors clearly for the first time, becoming part of popular politics (photos were often stuck in hats, sold and brandished during speeches) and of course making it possible for politicians to be recognised. In so doing they helped to create the imagined ‘personal’ relations that still underpin our responses to our leaders: how do they look? How do they speak? Are they likeable, dynamic, convincing, trustworthy? Being recognisable also brought new perils: mistakes like the murder of Robert Peel’s secretary in 1843, misidentified as the prime minister, could no longer be made.

This is perhaps an unfair criticism of a book with ‘celebrity’ in its subtitle, but I wanted most of all for more attention to be paid to the anonymous or historically insignificant men and women whose private pictures constitute the largest part of the enormous photographic bequest left to us by the 19th century. Frecker has a moving chapter – probably his best – on photos of the dead or dying, most of them children, shown with or without their parents. He is careful to look beyond the images to consider their circumstances: the imperatives and timings of parents’ or relatives’ decisions, the dislike of many photographers for the work, the way bodies or still-living persons were moved into better light, the women who came into the studio and unrolled a bundle to reveal a dead baby (individuals and families also posed in mourning, sometimes with the headstone of a loved one).

Some people wanted photos of themselves accompanied by the tools of their trade, and Frecker includes pictures of a postwoman, a butcher, two drapers, several carpenters, slop workers with sewing machines, a fireman, an ammunitions manufacturer. He also explains the bizarre figure of the ‘hidden mother’: a parent would hide under blankets to hold a young child firmly in place on their lap, rendering themselves a dark human-shaped lump in the background. And throughout he allows us to see the strange multitude of backdrops and props, some most unsuitable to the subject: all those swag curtains, painted balustrades and libraries; but also stuffed dogs, boats floating in fake lakes and fake falling snow. But heartened as I was by all the life conveyed in these images – often so mournful-seeming when found far from home in antique shops or car boot sales – still I sometimes wanted Frecker to zoom in closer, to see what might be gained by intimacy rather than expansiveness. When I look at Victorian photos, or at the two dozen or so cartes de visite I own (which once or twice have vaulted me over writer’s block by providing the features for a fictional character), I often find myself dwelling on the positions taken by feet and fingers, the relation between lips and eyes, how close people stand: those constant features of life in a human body. They seem to offer the most vivid access to that brief but persisting moment in time. It’s nice to think, too, that these men and women were able to step in front of the camera, get rid of their poses all in one go, and then return to the business of living.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.