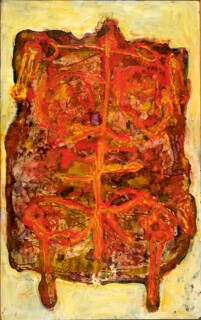

In July 2007 I drove west from New Haven for eight hours to Getzville, north of Buffalo, to meet Magda Cordell. She was then in her eighties; I wanted to ask her about life as an artist in London in the 1950s. Born in Hungary, Cordell had arrived in Britain after the war with her husband, the composer Frank Cordell, and soon became part of the London scene. She was the only female painter in the Independent Group, a band of artists, architects and designers who hung out at the Institute of Contemporary Arts on Dover Street. She made her name in the mid-1950s, with images of flattened female bodies, painted on canvas in a sort of rich goulash of oil and acrylic.

Two of these bodies, Figure 59 (1958) and No. 8 (1960), are included in the exhibition Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-65 at the Barbican (until 26 June). They hang on either side of the more reticent Standing Female Figure, a bronze by William Turnbull, whose textured surface and swathed upright form suggests a mummified Giacometti. The pairing illustrates how unusual Cordell’s paintings were in going beyond the inhibition and deference to French and American art that mark much British work of the period. Only Francis Bacon shows the body disrupted and distorted as she does.

Cordell’s work, and what one critic called her ‘legendary panache’, should have ensured her a place at the forefront of British art. She was praised by critics and had successful exhibitions at the ICA and at the Hanover Gallery, a centre for émigré artists run by the German dealer Erica Brausen. After Cordell moved to America in 1961 with the man who became her second husband, John McHale, she was largely forgotten in Britain. The sculptor Richard Smith, and McHale himself, suffered similar neglect after leaving the UK.

By the time I visited her, Cordell’s memories of the 1950s were patchy. For long stretches we said little. She smoked Carlton 100s and showed me a few collages by McHale that she kept in a portfolio in her wardrobe. There was some conversation about her frustrated attempts to paint in the retirement home – the staff were always confiscating her materials. ‘Why are you all interested in my painting now?’ she asked towards the end of my visit. ‘You weren’t interested then.’

I’ve often wondered which ‘then’ Cordell meant – her time in London or America. Perhaps she simply meant the time when it would have made a difference to her life. Postwar Modern is not the first exhibition to place her work in context. A number of her paintings were included in Transition: The London Art Scene in the 1950s, a show at the Barbican twenty years ago. Postwar Modern offers a broader selection of work than that exhibition, situating British artists alongside arrivals from Europe and the former colonies in South Asia and the British West Indies. ‘Postwar’ seems less a historical period here (the majority of the works were made after 1955) than a matter of style: a deliberate roughness of surface, a focus on the fractured body – not tastefully fractured, as in Cubism, but genuinely stamped on, scraped and torn apart. The effect is threatening, a sort of post-Neo-Romanticism, heavy with meaning, but also shot through with traces of levity and optimism. A ‘doublethink’, you might say, of grief and joy, such that the ruined world could become an object of admiration. ‘It was sexy in a way, this semi-destroyed London,’ Frank Auerbach later recalled. Auerbach’s portrait of his cousin Gerda Boehm, included here, is made with layers of mottled and crusted paint, and hovers between saying something about the ‘human condition’ and simply delighting us with its colour and substance, like an eye-catching dessert. David Sylvester described looking at a painting by Auerbach at the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1956 as like ‘running our fingertips over the contours of a head near us in the dark, reassured by its presence, disturbed by its otherness’.

By including the work of so many émigré artists, the exhibition presents this ‘otherness’ as essential to the postwar style. The Warsaw-born artist Franciszka Themerson arrived in London during the war, where she worked with her husband, Stefan, making films for the Polish Film Unit, as well as founding the Gaberbocchus Press, which published the first English-language edition of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi. The two smiling homunculi in her 1959 painting How slow life is and how violent hope (a line from Apollinaire), who might be figures from the play, appear bound together by lines gouged in the dirty white paint – ‘modern cave paintings’, in the words of one contemporary critic. Themerson often included an upside-down figure representing herself in her paintings – as elemental a metaphor for the émigré experience as you could hope for. If her paintings are ‘quintessentially postwar’, as the show’s curator, Jane Alison, puts it, then that seems again to have more to do with surface texture than with subject. Visiting a Mondrian retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1955, Themerson wrote that she remembered the ‘old, withered woman who was sitting there in the corner, knitting’, as much as the work itself.

That ‘old, withered woman’ could have been one of the Whitechapel residents recorded by the German-Jewish artist Eva Frankfurther. Frankfurther arrived in Britain in 1939, aged nine, and trained at St Martin’s School of Art alongside Auerbach and Leon Kossoff. Her paintings, a record of the changing face of East London in the 1950s, are done in a style that harks back to German artists of the 1920s and 1930s, in particular Käthe Kollwitz and Karl Hofer, who themselves belonged to a tradition of proletariat painting stretching back to Daumier. They might not have the force of Lucian Freud’s portraits, but Frankfurther’s paintings hold their own, finding something distinctive in their evasive and melancholy subjects. They couldn’t be further from the proto-Pop world of the Independent Group, or the futuristic and dystopian imagery on display at the Whitechapel exhibition This Is Tomorrow in 1956, when Frankfurther was living in the area. We don’t know what she might have done next: she killed herself aged 28 and, like Cordell, was more or less forgotten. Not a single example of her work can be found in the Tate.

Francis Newton Souza emigrated to London from Bombay in 1949. His series of ‘black art’ paintings from the mid-1960s, in which figures and faces are incised on a thick layer of black oil paint, visible only at certain angles of light, are concise metaphors for the invisibility of colonial subjects. Souza wrote about this invisibility in his essay ‘Nirvana of a Maggot’, an account of living and painting in a poor village in Goa, published in Encounter in 1955:

I myself read, write and think in a language alien to me: English, a language not my mother tongue but spoken to me by my mother since my childhood. But the difficulty in expressing myself arose from the very start … how can one articulate in Anglo-Saxon with a jewelled mandible that was fashioned by the ancient Konkan goldsmiths of Goa?

The problem of articulation is present in the work of other émigré artists, in the Paul Klee-like paintings of Anwar Jalal Shemza and in the work of Avinash Chandra, both of whom moved to London in 1956 (from Pakistan and India respectively), but it is also a problem of postwar art-making as a whole. In Germany the dilemma was existential: how could you make ‘German’ art when all links to tradition seemed to have been broken? A similar question was being asked, in a smaller way, of the claims to the new era that could be made by ‘British’ art, which seemed a world away from Paris, still the centre of modernity it had been before the war.

Postwar Modern makes the case for British art through a series of telling comparisons, and not only between émigré and British-born artists. Francis Bacon and David Hockney might seem to occupy different spheres, but bringing together a small selection of their paintings from the 1950s proves that they were, at least at one time, sides of the same coin, both using half-lit figures against dark backgrounds to register a coded and circumscribed sexuality. A different sort of intimacy is summoned by the juxtaposition of portraits by Lucian Freud and Sylvia Sleigh with photographs by Bill Brandt. Brandt’s images, published in the book Perspective of Nudes (1961), show naked women in interiors that resemble film sets, shot with a wide-angle, fixed-focus Kodak, a ‘police camera’ used to document crime scenes. The bodily distortions are dreamlike and eroticised, closer to voyeurism than Surrealism. The titles emphasise the link to cinema: The Haunted Bathroom, Campden Hill shows a heavily made-up woman baring her breasts, while The Policeman’s Daughter, Hampstead shows a young woman sitting naked in an upright wooden chair, half turned towards us. A bright light illuminates her body, throwing dark shadows across the floor, and making her appear strangely monumental against the bare backdrop of the bedroom in which she poses. It’s eerie without being contrived, like a scene from a novel by Henry Green.

Brandt’s formal attitude here is well matched by the cold intimacy of Freud’s portraits of Kitty Garman and Caroline Blackwood. But in other respects these crisp early Freuds seem the antithesis of the postwar style. Girl in a Green Dress (1954), a painting of Blackwood, details every lash, every freckle on her face. Within a few years Freud was making more freely brushed paintings, such as Woman in a White Shirt (of Deborah Cavendish), which in their impasto painterliness appear more properly ‘postwar’, companions to Auerbach, Kossoff and also Bacon (whose influence helped bring about this shift in style). Freud was no émigré, even if he looked down on British social mores: ‘The clockwork morality of Britain that one feels on a bus, the inhumanity, the rigidity – it’s a wonder anyone paints at all.’

Sylvia Sleigh’s two delicate portraits of her young lover, Lawrence Alloway, dressed as his alter ego, the primly named Hetty Remington, are ripostes to the one-way stares of Freud and Brandt: here is a relationship based on mutual exchange. The Bride (Lawrence Alloway) and The Bride with Petunias, made a few years before Sleigh divorced her first husband, Michael Greenwood, and married Alloway, hung in Alloway’s flat in Blackheath, and were admired by Cordell and McHale but were not exhibited in public for decades. (It would be interesting to know where and when they were first shown.) If Freud’s work is characterised by cold surveillance, these images suggest a tactfulness both in the encounter between artist and lover-subject, and between brush and canvas – nothing is delineated or demanded, everything is suggested, evoked. Like Cordell, Sleigh was largely forgotten in England after she and Alloway left for America in 1961. Just one of her paintings entered a British collection during her lifetime, a group portrait called The Situation Group (in the National Portrait Gallery), which consists entirely of male artists, except for the painter Gillian Ayres.

The Situation Group would have been a good addition to Postwar Modern, both to have a bit more Sleigh, and as a reminder of how few female artists were recognised at the time. Hung towards the end of the exhibition, Ayres’s Break-Off (1964), which shows scorched, splashed and heavily brushed shapes on a stormy white ground, seems to burst open a new era of image-making – ‘post-postwar’, perhaps. Meaning is no longer concentrated in fractured bodies or expressed in moody textures, but is part of a wider environment of physical participation, shaped by the idea of ‘action painting’: the viewer is enveloped by a painterly atmosphere, the gallery transformed into a stage. There is also a sense of pleasure, of sheer beauty, that would have seemed out of place, even grotesque, a decade earlier. Although these were the early years of Pop and Op, Postwar Modern stays true to its theme: instead of Kitaj, Blake, Boty or Riley, there is Gustav Metzger’s Liquid Crystal Environment, a room in which you can contemplate, like a latter-day Des Esseintes, projected images of coloured forms created by heat-sensitive liquid crystals; and Frank Bowling’s Big Bird, showing his swan motif flying into an American-style Colour Field painting – both works from the show’s closing year of 1965. The point is well made: ‘postwar’ was not simply overwritten by the unbridled optimism of Pop, but lingered as an almost romantic spirit. Auerbach is making postwar art to this day.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.