In Antony, the southern suburb of Paris where Louise Bourgeois spent her childhood, the river water had special properties. The Bièvre, which ran past the Bourgeois home, was thick with tannin, an important ingredient for the family’s tapestry restoration business: wool washed in this water is more receptive to dyeing agents – colours set fast and don’t fade. Her father’s first job was as a landscape architect and he would bring back decorative garden sculptures from his travels across Europe. They always needed to be repaired and straightened up. ‘It is partly why I became a sculptor,’ Bourgeois said. ‘I was so familiar with them.’ After the war, he began to collect tapestry fragments, drawing on his wife’s knowledge to restore and reshape them (she had worked in her family’s tapestry atelier in Aubusson, where the river Creuse, like the Bièvre, coursed with tannin).

Little Louise, sometimes known as Louison, was brought into the family business aged eight as dessinateur, at that time an exclusively male role. On Thursdays and Sundays, when she wasn’t at school, her job was to draw in the missing sections – often bodies or parts of them. She started with the feet. At fifteen, Bourgeois left school altogether to work in the weaving and restoring ateliers full time, while preparing for the École des Beaux-Arts. The house was filled with stacks of tapestries and as a child she would fold herself inside them to keep warm or to hide – they were ‘a form of textile sculpture to be entered’, she said, a rich, immersive material.

The Woven Child at the Hayward (until 15 May) is the first large-scale retrospective of Bourgeois’s textile works, made from the mid-1990s until her death in 2010. Her work with cloth is varied, prolific and innovative; many pieces offer new iterations of familiar Bourgeois themes – memory, sexuality, identity, the body, pain, love and most of all, perhaps, the compulsion to make. Created late in her life, they are themselves retrospective, made from the stuff of her life – personal garments, domestic linens, needlepoint, embroidered handkerchiefs, scraps of tapestries brought to New York after her father’s death. ‘Having held onto these objects of clothing for a lifetime,’ her assistant, Jerry Gorovoy, wrote shortly before her death, ‘by incorporating them into her art she alleviates her fear of separation. This processing is connected to the fear of dying. The need to mark time, which is what these clothes represent, is connected to her awareness of her own fragility.’

As a child, Bourgeois’s parents competed with each other to dress her in the latest fashions: ‘Chanel, Poiret, lingerie Suisse, furs, foxes, boas’. This elegant and sometimes idiosyncratic style remained with her throughout her life: who could forget the image of her outside her Manhattan townhouse in a brown latex costume of coarse, bulbous forms; or the 1982 Mapplethorpe photograph in which she wears a luxurious fur coat and holds her sculpture Fillette: a giant latex phallus she referred to as her ‘doll’. It wasn’t until she was in her eighties, however, that she began to think of clothes as sculptural elements – intimate, indexical, mnemonic. ‘You can retell your life and remember your life by the shape, the weight, the colour, the smell of the clothes in your closet,’ she said. ‘Fashion is like the weather, the ocean – it changes all the time.’

Bourgeois had all the clothes, fabrics and textiles from her closets brought down to the basement studio and hung over the pipes according to colour. Those that evoked particular places, people or memories remained whole, while others were cut up and repurposed, stitched together, often crudely, to form heads and other corporeal elements. In Untitled (1996), eight pieces of clothing are suspended at different heights from a central steel pole; they radiate round it like ghostly, drifting bodies. Two silk slips, one carefully edged in lace; four delicate chemise-like vests, some frilled or with a necktie, others fastened at the side with silk-covered buttons; a pale pink pussy bow shirt; and a shimmering, beaded black cocktail dress hang on cow bones whose rounded joints extend through the arms of the garments. The pink shirt and black dress are gently padded, to remind us that these garments once held bodies. The words ‘SEAMSTRESS’, ‘MISTRESS’, ‘DISTRESS’, ‘STRESS’ are welded to the base – evidence of her childhood and of its vexing memories (her father was a serial philanderer who carried on a long affair with her young governess, among other tyrannies).

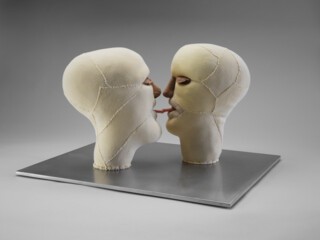

The body is spectral and absent in this work, but in others it is all too present – large, stuffed, heavy, sagging. Single I (1996), a body without hands, feet or a head, is made from a number of grey-toned fabrics and hangs upside down in the Hayward’s brutalist stairwell, arms extended like Saint Peter, tiny round breasts protruding. High up, over a doorway, Legs (2001) is a cluster of three enormous red patchwork limbs suspended from metal wires; in the centre of another room hangs Spiral Woman (2003), faded black fabrics stuffed and sewn in a spiral that gives way to a pair of slender, dangling limbs. ‘The spiral is somebody who doesn’t have a frame of reference,’ Bourgeois wrote. ‘The only thing is this hanging, this fragility.’ A series of eleven heads made between 1998 and 2009 demonstrates her virtuosity and her attention to the particular qualities of fabric. The materials include wool, felt, muslin, tapestry, cotton, terrycloth; the heads appear to grimace, open their mouths in anguish, stare or implore. Some have no face, while others have three. Two heads, covered in raised seams that look like scars, face each other and touch the tips of their extended pink tongues. This is the heroic classical bust made soft and slyly weird.

In other works, bodies are enclosed in structures (Bourgeois called them ‘cells’) made of glass, wood, steel mesh, repurposed windows and doors; or arranged in dioramas. Visitors may already be familiar with some of these – small, pink, seam-covered bodies, often female and in various hybrid states – a selection of which were recently displayed at Tate Modern in a room devoted to Bourgeois. I was most surprised by Couple III and Couple IV (both 1997), large vitrines, each containing two headless black fabric figures lying on top of one another, like giant poupées abandoned in an inert romance. (If only they could love each other, I thought, quickly ashamed at the idea of their animation.) In Couple III, one figure wears an elaborate pink arm brace; in Couple IV, one has a wooden leg laced up its thigh in leather. For Bourgeois, the body imagined through fabric was a visible – and haptic – site of pain and loss. ‘The subject of pain is the business I am in,’ she said. ‘To give meaning and shape to frustration and suffering. What happens to my body has to be given a formal abstract shape. So you might say, pain is the ransom of formalism.’

Bourgeois described her ‘cells’ as representations of different types of pain, but they are also highly controlled display mechanisms that marshal how and what we are allowed to see. As in much of her work, the status of the materials is ambiguous: what contains or constricts also shelters and protects. Are we voyeurs, observing moments of private suffering, or has our attention been drawn to something special, arranged with love and care? In Spider (1997), a large, circular steel cage is enclosed by the angular legs of one of Bourgeois’s spiders, its body nestled in the top of the structure. Fragments of tapestries are fixed to the exterior and interior walls of the cage, and draped over an upholstered chair at its centre. Little Louise, now grown up, has not repaired the missing pieces of the tapestries, however, and it appears some images have been deliberately excised: the face of a king, the crotch of a naked child. Bourgeois’s work asks what we do with the past – particularly when it remains painful or in pieces, moth-eaten.

Three of her special edition fabric books – The Woven Child (2003), Ode à l’oubli (2004) and Ode à la Bièvre (2007) – are displayed page by page alongside a series of works from the mid-2000s that continue her spiral and web motifs. In these pieces, all untitled, swathes of coloured and striped cloth have been cut into triangles and tightly stitched together to form circles and patterns, which radiate outwards from fixed points. Some have small fabric flowers at their central nodes. Others have been turned over, revealing the network of intricate seams on the reverse and drawing attention to her labour. ‘Where do you place yourself, at the periphery or at the vortex?’ Bourgeois asked, with reference to these works:

Beginning at the outside is the fear of losing control; the winding in is a tightening, a retreating, a compacting to the point of disappearance. Beginning at the centre is affirmation, the move outwards is a representation of giving, and giving up control; of trust, positive energy, or life itself.

In two late works from 2009, Eternity and Eugénie Grandet, the spiral becomes a clock face. Next to each number in Eternity is a pair of torsos, male and female, painted by Bourgeois on a square of fabric and then sewn onto the main piece, a vast white sheet. In blues, pinks, reds and inky blacks, the two bodies face each other – penis erect, stomach swollen – in eternal tumescence. Eugénie Grandet is quite different: a small sixteen-piece needlepoint ode to Balzac’s lonely heroine. Each white rectangle of fabric – muslin, linen, cotton, striped, checked – is embellished or embroidered with small objects: tiny jewels, flowers, clasps, buttons, needles. There are three clocks, each showing a different time, and another with no hands at all, only a tight bouquet of purple flowers. This is Bourgeois at her most conventionally unconventional, feminine, careful and neat, reminding us that such delicate work is associated with childhood and old age, that it can be an act of devotion. Sewing, Bourgeois wrote, ‘is a plea in favour of a/second chance, it is a plea in favour of/X and against Y.’ If severing and cutting were connected with the father, sewing was associated with the mother. ‘My mother would sit out in the sun and repair a tapestry or a petit point,’ she recalled. ‘This sense of reparation is very deep within me.’ Bourgeois liked to invoke the spider and the caterpillar – creatures that draw transformative materials from within – as emblematic of artists. The woven child, Louise, Louison, is both maker and made, weaver and woven.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.