Alice Neel was born in January 1900 and grew up in a conservative town in rural Pennsylvania. She ‘couldn’t stand Anglo-Saxons’, she later said, ‘their soda-cracker lives and their inhibitions’. In 1921, she quit her job as a secretary for the US air force and enrolled at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. She was influenced by the work of the American painter Robert Henri, who had founded the Ashcan School – a movement that championed gritty depictions of urban scenes. ‘I didn’t want to be taught Impressionism,’ Neel explained. ‘I didn’t see life as Picnic on the Grass. I wasn’t happy like Renoir.’ Her latest retrospective, Alice Neel: Every Person is a New Universe, at the Munch Museum in Oslo (until 26 November), brings together 59 of Neel’s paintings and drawings from across six decades.

In 1925, she married Carlos Enríquez, an artist from a wealthy Cuban family. The couple spent a year in Havana and the work Neel produced there shows Henri’s continuing influence. She painted the people she saw on the streets, though she disliked the term ‘portraits’ (too bourgeois) and preferred to call her paintings ‘pictures of people’. Mother and Child, Havana (1926) is filled with movement, the thick, muscular brushstrokes affording a special clarity to the face of the little girl in a pink dress, who sits on her mother’s lap. Beggars, Havana, Cuba from the same year shows Neel’s interest in capturing scenes of human privation. Two loosely painted figures sit on a bench, the bright glare of the sun illuminating their worn clothes. The man sits up straight, a hint of a smile on his face, while the woman beside him is slumped, her body turned away from the painter’s gaze.

Neel and Enríquez returned to the US in 1927, and soon separated (divorce was also bourgeois). Their first daughter, Santillana, died of diphtheria shortly before her first birthday; their second, Isabetta, was taken back to Havana by Enríquez and raised by his family. Shortly after this, in August 1930, Neel had a breakdown, and attempted suicide; she was institutionalised for almost a year.

After she recovered, Neel moved to Greenwich Village and began painting queer couples, ethnic minorities, activists, artists, trade unionists – those who faced discrimination or suffered for their non-conformity:

There’s a tendency in the human race to make everybody alike … to homogenise the world. I saw the world as difficult. I saw the pressures as terrific … the pressure to be normal. Besides everything else that you have to do, they invented these frightful shirts that have to be laundered and buttoned and you’re even supposed to put on a tie. But all those things were very difficult for me. To keep up with all the things of regular life makes you absurd.

The works Neel made in the early 1930s were fleshy, funny, sometimes tender, often brazenly erotic. Nadya and Nona (1933) combines aspects of Surrealism with the dark post-expressionism of New Objectivity. Two female lovers lie in a kind of dreamscape: the wrinkled green bedcovers beneath them form marshy ground and a moody sliver of sky with a full moon hovers beyond. In Joe Gould, painted around the same time, the (often homeless) oral historian of Greenwich Village sits on a barely sketched red stool. Three penises, in hues of crimson and beige, dangle between his legs like a phalanx of inverted onion domes. Kenneth Doolittle (1932) shows one of Neel’s lovers, a sailor with leftist sympathies and an opium addiction, fast asleep, his naked form captured by her characteristic dark, unbroken outline – arms folded over his chest, legs spread, one knee bent. A crucifix is fastened low on the wall above the bed, lending the work a little obscenity.

These sensual images would not be exhibited until 1970. From 1934 to 1943, Neel was employed by the Federal Art Project – part of Roosevelt’s New Deal programme. She was assigned to the ‘easel division’, along with artists from Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock to Jack Levine and Philip Evergood. She concentrated on works of social realism, attempting ‘to catch life as it goes by, right hot off the griddle’. Longshoremen Returning from Work (1936) shows waterfront labourers – whose general strike of 1935 had been a catalyst for widespread industrial action – making their way home through grey, early evening streets. Uneeda Biscuit Strike, from the same year, is more overt in its sympathies. It shows a group of picketers being trampled by police horses as women and children look on in horror.

The Work Projects Administration wasn’t an easy fit for Neel and the organisers found some of her works unsuitable for display in public buildings. One painting was destroyed for being ‘indecent’ (nudes were forbidden); another, of a fish market, had to be amended because there was too much blood. When the WPA was abruptly terminated in 1943, and public funding redirected towards the war, Neel and others learned that their work was being thrown out, sold or even repurposed as ‘oiled canvas’ to wrap pipes. She managed to buy back around ten of her paintings.

By this time, Neel had two sons, one with the Puerto Rican singer José Negrón and another with the filmmaker Sam Brody. After Negrón left her, Neel remained in their apartment in Spanish Harlem, which doubled as a makeshift studio. Amid the fervour for Abstract Expressionism, she continued to paint people, including many of her Hispanic neighbours. The Spanish Family (1943) is a tightly grouped composition showing Negrón’s sister Margarita with her three children. The baby in her arms, rendered in sketchy lines, refuses to stay still. Neel returned again and again to the subject of mother and child (or children). Although Margarita is the firm centre of the image, it’s the children that transfix us: the boy with his knowing look, the girl glancing warily beyond the frame.

Neel’s grisly 1960 portrait of Frank O’Hara (‘it’s too hatchet-faced,’ she later told Ted Castle) ushered in an era of large, vivid and often sparely-painted canvases, whose energetic lines and idiosyncratic perspectives nod to abstraction without ever fully embracing it. This new style is evident in Ruth Nude (1964), where blue and yellow forms swirl around the freely drawn subject sitting casually with one bent leg raised, genitals exposed. As a portrait it’s neither flattering nor scrupulous, but seems to exist outside of these categories. Neel took liberties with anatomy – Ruth’s left arm is weirdly articulated – in order to keep a sense of movement, just as she used exaggerated outlines and bright colours to add drama and emphasis.

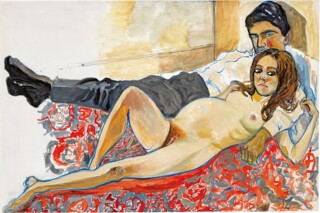

One of the most arresting works from this period is Pregnant Julie and Algis (1967). The foreground of the image is dominated by the bulging stomach of the otherwise slight Julie, whose kohl-rimmed eyes regard us apprehensively. The red and grey carpet beneath her threatens to rise and engulf her form. Neel was aware that in painting pregnant nudes she was bucking a trend: ‘I feel as a subject it’s perfectly legitimate, and people out of a false modesty, or being sissies, never show it … Something that primitives did, but modern painters have shied away from because women were always done as sexual objects. A pregnant woman has a claim staked out; she is not for sale.’

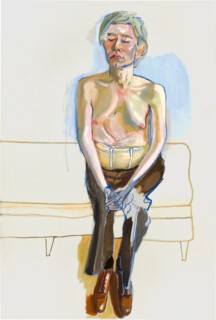

Neel rose to prominence in the late 1960s with the emergence of second-wave feminism. In 1970, on the back of a petition organised by the feminist art historian Cindy Nemser, her work appeared for the first time in the Whitney’s annual exhibition. The same year, Neel completed Andy Warhol, the painting for which she’s perhaps best known. It was the second time Warhol had posed for an artist since the extensive surgery that followed his shooting by Valerie Solanas (the first was Richard Avedon) and Neel shows him looking diminutive, eyes closed, hands barely sketched and his left knee unpainted, as if his body is coming or going, or both. The scars criss-crossing his torso are picked out in flecks of pink. Light seems to radiate from his placid face.

Neel encouraged her sitters to ‘assume their most characteristic pose, which in a way involves all their character and social standing – what the world has done to them and their retaliation’. But she was also keen to emphasise the formal qualities of her work: ‘You see, I’m not just a simple figure painter. The abstract elements and the geometric layout of the canvas are very important to me.’ Her art is most radical for its non-dogmatic, non-prescriptive character. Despite the evidence of what the world ‘has done’ to her sitters, her portraits are never mawkish. She kept something back: wasn’t it more fun, she said, to play hide and seek with her thoughts, ‘to hide them artfully in little corners?’

Earlier this year, the Barbican showed more than seventy of Neel’s works in Hot Off the Griddle, the largest UK exhibition of her paintings to date. The show opened with a late nude Self-Portrait (1980), completed four years before her death. Neel paints herself perched on a blue-and-white-striped chair, her white hair swept up in a grandmotherly bun. Her body is outlined in the same blue as the chair, and she wears nothing but a pair of yellow-rimmed glasses and a somewhat disapproving expression. One hand lifts a brush like a conductor’s baton, the other dangles a white cloth. A foot appears to dance impatiently, but this is Neel’s usual frankness – she had flat feet and a prehensile big toe. ‘All my life I wanted to do a nude self-portrait,’ she told Newsweek. ‘But I put it off till now when people would accuse me of insanity rather than vanity.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.