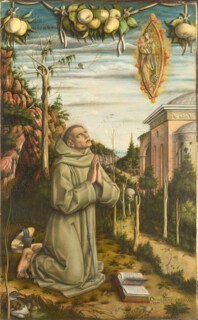

It takes about ten minutes to walk from Birmingham New Street Station to the Ikon Gallery, which occupies one of the few Victorian buildings to have survived the redevelopment of the city centre. Above the excellent café and a shop, the white walls of the first floor, where contemporary art is normally displayed, are at present devoted to Carlo Crivelli (until 29 May). Most of the paintings have been borrowed from the National Gallery but there are major loans from elsewhere, including an exquisite panel from the Victoria and Albert Museum and the central panel of a grand altarpiece now kept in the Vatican Museum.

Among the loans from the National Gallery is the Annunciation (1486), one of the best-loved Renaissance paintings in London, in which Crivelli exhibited his knowledge of linear perspective in the recession of bricks and ashlar and the foreshortened apertures of a distant dovecote, and demonstrated his familiarity with the revival of ancient Roman ornament in the gilded Corinthian capitals and the terracotta relief of putti. But the impossibly elongated fingers of his Madonnas here and elsewhere reveal an attachment to late Gothic ideals, and the pierced and crocketed frames surviving on some of his polyptychs are spectacular examples of Gothic architecture. Crivelli seems to belong to two worlds.

He was not alone, in the final decades of the 15th century, in often retaining gilded backgrounds, but he had no rivals in decorating the gold with sharply incised and minutely punched patterns. He was also unusually skilled in building up the gesso ground of his panels into low relief, using the technique of ‘piping’ which is now only employed for embellishing the icing on a cake. He chose patterns that were difficult to render with the bladder and quill he must have used, giving the Virgin in the V&A’s panel a robe embroidered with long-beaked, long-tailed, long-winged birds, where the numerous fine raised lines often taper to a point. These are phoenixes which have migrated from Chinese textiles. Amanda Hilliam, in the excellent catalogue entry for this painting, likens the effect of this relief to that of the press-moulded silver foil which is a feature of many Byzantine icons, illustrating one from the 13th century in the cathedral of Fermo.* Such ‘Greek’ images, not all of them old, were found in many, perhaps most, homes of moderate affluence in Crivelli’s native Venice.

‘The Vision of the Blessed Gabriele’ (c.1489)

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.