The defeat of the Mamluk Empire in 1516-17 is the most significant conquest most people have never heard of. In the space of six months, Ottoman armies marched from Aleppo to Cairo, routed the Muslim Mamluk dynasty and seized territory that is now Syria, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Egypt and (parts of) Saudi Arabia. One moment the Ottomans were a regional power, the next they had an empire with intercontinental reach. Previously on the margins of the Islamic world, now they occupied its most prized religious and cultural centres. But the victory was just as important for the gateways it opened to other parts of the world: North Africa and the western Mediterranean, where the Spanish were expanding their influence; the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, where the Portuguese were elbowing in on local trade; and Iran and Iraq, where the Shiite Safavid dynasty was establishing its rule. The Ottomans would push forward on all these fronts in the following decades, joining a global contest for power that ranged from Mexico to Manila.

This is the story that Alan Mikhail, a professor of history at Yale, recounts in God’s Shadow. While the history of global competition isn’t new – to scholars at least – Mikhail places the Ottomans and their fellow Muslims at its centre, drawing on recent research to show that Ottoman, Mamluk and Persian domination of East-West trade routes necessitated European oceanic exploration, as did the fantasy of forging a global anti-Muslim alliance with the Great Khan of China. The threat of Ottoman military expansion helped ensure the success of the Reformation, since it forced the Catholic Habsburgs to call on Protestant military and financial support. And although Muslim states never established a formal foothold in the Americas, the culture and institutions they created did.

Before Columbus began his search for India, he had led an expedition to Tunis to recover a vessel seized by Muslim corsairs; he had also worked for a Genoese trading house in Chios, in the Ottoman-controlled Aegean. In the years that preceded the founding of Jamestown in Virginia, John Smith had fought Ottoman armies in Eastern Europe and spent time as an Ottoman captive. It’s no surprise, then, that many of the conceptual frameworks that European colonisers applied to the Americas derived from their encounters with Muslims at home: they compared Native American religious sites to mezquitas (mosques), called the nomads of Central Mexico alarabs, and referred to the offspring of Portuguese fathers and indigenous mothers as mamelucos. The infamous Requirement (Requerimiento), a Spanish legal document offering indigenous populations the choice between conversion and conquest, was based on jihad as practised by Muslims in medieval Iberia. The tribute (tributo) the crown collected overseas emulated the Islamic poll tax (jizya), also adapted by the Spanish from their Muslim predecessors on the peninsula.

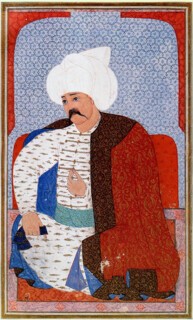

Mikhail’s narrative focuses on an unlikely hero: the Ottoman sultan Selim I (1512-20), who is usually overshadowed by his grandfather Mehmed II, conqueror of Constantinople, and by his son, Süleyman I, known in the West as Süleyman the Magnificent. Selim undoubtedly deserves greater recognition: he led the Syrian and Egyptian campaigns of 1516-17; he contained the Iranian Safavids, who presented an existential threat to the empire; and he crafted the clever alliances with Muslim corsairs that won him territory in North Africa at very little cost. All of this he achieved in the space of eight years, before his premature death from a boil in 1520.

Modern Western historians have sometimes overlooked Selim, but their Ottoman predecessors did not. Selim has a whole genre devoted to him, the Selimnames, or ‘tales of Selim’. Although these are mostly hagiographic, they originated in attempts to justify the sultan’s controversial path to power. Before Selim’s accession in 1512, the Ottomans followed a system that has been referred to as ‘succession of the fittest’. When a ruling sultan died, his sons had to fight one another for the throne. Although this could cause instability in the short term, in the long term it helped to ensure that the most skilled candidate, and the one with the largest support base, prevailed. Sensing that his ageing father, Bayezid II, favoured another son, Selim acted pre-emptively, and without precedent: he marched his troops on the sultan and escorted him to an early retirement in northern Greece. Bayezid died mysteriously along the way.

If 16th-century commentators were uncomfortable about the methods used to secure the throne, later historians have denounced Selim’s belligerent, even murderous legacy. He justified deposing his father on the grounds that Bayezid, a Sunni, was too soft on the Safavids. Selim had proved his military muscle against the Safavids as a young man, fending off repeated incursions and launching his own raids into Georgia, reportedly taking more than ten thousand captives in 1508 alone. His first war as sultan was against the Safavids, culminating at the Battle of Chaldiran in north-western Iran. But it is less Selim’s warmongering that unsettles contemporary historians than his actions at home: before marching east, he instructed his officials to undertake a census of people thought to be Safavid sympathisers. Many of those registered were promptly arrested, and many were massacred – forty thousand of them, according to one contemporary source. (Turkey’s Alevi community traces itself back to these persecuted groups.)

Mikhail does mention these outrages, but there is little room for Ottoman violence in his tale of Ottoman glory. He downplays the more unsavoury aspects of Selim’s character to portray him instead as the enlightened defender of secular, pluralistic rule. In doing so, he is addressing an American popular audience, attempting to counterbalance post-9/11 perceptions of Muslims as reactionary and fanatical. It is certainly true that the Ottomans have not always received due recognition for their impact on the modern world. They boasted modern Europe’s first standing army. They introduced the world not only to coffee, but to the distinctly Ottoman institution of the coffeehouse. They taught Europeans how to inoculate against smallpox. If anything, Mikhail insists, it was Europeans who were driven by a ‘culture of fire-breathing religious loathing’, what with their succession of Holy Leagues and incessant calls for crusades. To be fair, the Ottomans also made liberal use of anti-Christian rhetoric in their domestic and foreign policy, and Selim’s epithet, ‘God’s Shadow’, clearly signals his religious aspirations. Nevertheless, Mikhail is right to stress that the Ottomans did not eschew the Atlantic out of a lack of curiosity or economic savvy, as has sometimes been claimed. As masters of the Black and Red Seas, they already possessed what the Europeans had to leave the Continent to acquire.

Mikhail’s traditional, expository narrative mode and great-man accounts of battles and high politics may seem uncontroversial. But in September last year, shortly after its release in hardback, God’s Shadow became the subject of a Twitter storm. Three academics – Cornell Fleischer and Cemal Kafadar, both Ottomanists, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam, a global historian – wrote a spectacular takedown of the book titled ‘How to Write Fake Global History’. ‘Why a historian in a respectable university has been possessed to concoct this tissue of falsehoods, half-truths and absurd speculations remains a mystery to us,’ they wrote. As the tweets proliferated, the review penetrated ever deeper into historians’ circles. For some, it was a much needed dose of honesty; others saw it as ‘scurrilous and territorial’. In October, two scholars published a rebuttal, subtitled ‘God’s Shadow and Academia’s Self-Appointed Sultans’. A few days later, the original trio published a response to the rebuttal. By this time, the controversy had spawned its own hashtag (#Selimgate), numerous blog posts and an online poll asking how Mikhail ought to respond (a plurality advised he ‘accept flaws and revise’). Mikhail, perhaps wisely, stayed silent.

Why would scholars of the Ottoman past reject a book that places the empire they study at the centre of global modernity? To those who follow Turkish politics, the book seems to echo the nationalist rhetoric of Recep Erdoğan and his Justice and Development (AKP) party, who are all too eager to cite the historical role of Muslims in global politics, not least to justify their own geopolitical ambitions. In 2014, Erdoğan declared that Muslims had preceded Columbus in the Americas, adducing mezquita sightings as evidence. ‘As the president of my country, I cannot accept that our civilisation is inferior to other civilisations,’ he explained to an audience of Muslim leaders from Latin America. Though Mikhail, in a coda, clearly condemns this brand of AKP politics, his disavowal counts for little; this is a 400-page book that casts Muslims as heroes and European Christians as villains in a global morality play. The problem is not unique to Mikhail – scholars challenging popular misconceptions of Islam often earn the approval of Islamists – but Mikhail’s propensity for hyperbole does exacerbate the risk that his book will be deployed in support of bad causes.

Most Ottoman historians, I suspect, are broadly sympathetic to Mikhail’s goals: they regularly teach their students that the Ottoman Empire was a key player in Eurasian politics, that the European Renaissance developed in dialogue with the East, and that Islam was a flexible and ever-changing set of traditions. God’s Shadow, however, has a tendency to overstate these claims: it’s a stretch to say that in 1500 the Ottoman Empire ‘shaped the known world’ from China to Mexico. The humanists of Renaissance Europe did not view Islam as ‘a more compelling obsession than the classics of antiquity, art or personal salvation’. And it’s difficult to see how Selim can be credited with leading an ‘Islamic Reformation’: the law book Mikhail cites as evidence of this claim built on, rather than overturned, features of the existing sharia court system. The tone of ‘How to Write Fake Global History’ betrays an anxiety about ‘relevance’ – relevance of the sort understandable to commercial publishers and university administrators – and the fear that meticulous scholarship is being crowded out. It’s not that historians haven’t always been keen to address contemporary concerns, but most have also insisted on the complexity of historical processes.

Selimgate also played into ongoing debates about the project of global history. The field developed in the 1990s out of precisely the kind of presentist concerns that shape Mikhail’s book, as historians sought to understand the origins of their own globalised world. Yet after nearly thirty years, the project has diversified in its goals and increased in sophistication. In some ways, God’s Shadow is a product of these developments, in that it finds connections between seemingly disparate geographic regions and centres a non-European perspective (most early practitioners were scholars of Europe). But in other respects, the book falls short of modern standards. Though many global historians, like Mikhail, still rely mostly on secondary literature, others have done brilliant and careful work with primary sources. Many have focused not on elite men, but on women, enslaved people or indigenous groups. Many have made ambitious claims, but have grounded them in precise empirical detail. A few have even managed to be both scholarly and accessible.

It is this balance that God’s Shadow fails to strike. As the number of positive reviews in the mainstream press has suggested, the book has penetrated a wider market for Ottoman history dominated by military historians and non-specialists. Surely it is welcome that an Ottoman historian with expertise in Middle Eastern languages would add his voice to this chorus. That doing so comes at the expense of historical accuracy is not inevitable. What a pity it would be if young scholars of non-European history concluded from Selimgate that writing global history, or making historical work accessible, are projects best left to others.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.