The rubble had been cleared away, but strange grasses and wild herbs had sprung up where the war-demolished houses had been.

Muriel Spark, A Far Cry from Kensington

On the opening page of Craig Brown’s One Two Three Four, Brian Epstein and his personal assistant, Alistair Taylor, behold the Beatles for the very first time. It is November 1961, in a ‘dank and damp and smelly’ Liverpool basement, and the young band are loud, foul-mouthed, almost purposefully unprofessional.

After the show, Taylor says: ‘They’re just AWFUL.’

‘They ARE awful,’ agrees Brian. ‘But I also think they’re fabulous.’

There’s a hint of steely camp in that ‘fabulous’ of Epstein’s – but maybe, too, a significant subtext. Fabulous like a fable in the making. A fabulous opportunity, to pluck these no-hopers out of their airless oubliette and plant them somewhere entirely new. A fabulous creation, from the ground up. Fables per Aesop or La Fontaine often involve sudden and unlikely transformation: a burst of speech from creatures we never suspected had a voice, creatures whose designated role was mute acceptance of their hard-labouring lives. Epstein saw in an ESP flash that these lairy skiffle boys might have a future. He intuited other futures too: a completely new Britain, culture, world.

What was it exactly that Epstein flashed on but Taylor didn’t? Perhaps his own outsider status in postwar Britain – gay, Jewish, not situated quite precisely enough in the nation’s ossified class structure – afforded him a glimpse of a new kind of culture in which edgy outsiders would become glamorous commodities. Epstein’s quiet overhaul of the Beatles after he became their manager kept their abrasive life force intact inside a subtly codified front of tidy, polite charm. There would be none of the neutering effected by Colonel Tom Parker on Elvis. The Beatles’ class, accent and sex appeal weren’t glossed away, but finessed for a world beyond the raucous, claustrophobic clubs they were used to. This may be the moment subculture jettisoned its prefix, and began to infiltrate the culture at large.

The jacket covers of two of these new Beatles books feature the classic mid-1960s Fab Four: no longer buttoned up inside matching suits, but individually tailored in tasteful shades of black, brown, beige and grey, hair midway between moptop and Maharishi, out in the open air pretending to play and – maybe with a little help from a sneaky lunchtime joint – enjoying the pose. They only had to open their mouths to reveal their backgrounds, but these images show young men at large in the world who aren’t the factory fodder of British New Wave cinema, or arty middle-class drop-outs either. Not quite the Mods next door, they’re the modernists you might take home to mother: both deeply ordinary, and something entirely new.

Later in the decade, Lennon and McCartney would both visit the wilder shores of avant-garde art/pol, though it was the Rolling Stones who summoned Dionysus and Pan, with their none hipper retinue: Kenneth Anger, Christopher Gibbs, Gram Parsons, Jean-Luc Godard. The Beatles grew sheepdog hair and Bakunin beards, and adopted the statutory exotic guru, but they never really had anything like the Stones’ sullen, dandified grandeur. The Stones were exquisites; the Beatles were Everyman. It’s the Beatles’s admixture of pop and art, commerce and experiment, which now seems to prefigure so much of the mass culture to come. The attempt to turn the Apple record label into a multi-tentacled brand, for instance, predicts a lot of what we now take for granted as consumers. The Apple Boutique, with its tingly visual environment, was part hipster Woolworths, part multimedia experience, part chill-out room: a space where the music you liked and who you worshipped and how you dressed weren’t discrete entities but linked-up ‘lifestyle choices’. It now looks like our current Goopy moment of wellness and crystals, beard care and curated playlists. As with the Beatles album sleeves designed by Peter Blake and Richard Hamilton, this was where art and pop first locked eyes, before deciding to move in together.

Ahalf-century on from the band’s messy divorce, you don’t have to go searching for Beatles bumpf: it’s everywhere. They’re as much a part of the public conversation as they ever were. Here is an incomplete log of Beatles sightings I kept as 2020 tiptoed hesitantly into 2021: in a Pierre Cardin obituary; in a Gerry Marsden obituary; in a documentary about J.D. Salinger; in one of Netflix’s numberless true crime productions (viz, a reconstructed FBI interview with Charles Manson, peddling his ‘blame it on the Beatles’ spiel); a ‘previously unseen’ Beatles-at-home photo from 1963; a ‘previously unseen’ Beatles photo at Shea Stadium from 1965; a hip young mixadelic band citing ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ as the track that turned their heads around; Don Henley, in an Eagles rockumentary, likewise hailing ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ as a ‘revolutionary’ moment; the broadcaster Samira Ahmed holding a framed still from a favourite film, A Hard Day’s Night; an essay by Eula Biss referring to Paul McCartney and ‘Norwegian Wood’; McCartney sporting a man bun during his lockdown vacation; rave reviews for McCartney’s new lockdown solo album; various reflections on the fiftieth anniversary of George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass; various reflections on the fortieth anniversary of John Lennon’s death; a trailer for Peter Jackson’s new Beatles documentary, Get Back; a new documentary about Mark David Chapman; an article trailed as ‘the inside story of how Bowie met John Lennon’; a lockdown viewing of the dreary Richard Curtis film Yesterday; a mystifying Japanese tweet, apparently about Ringo.

And those are just the ones I remembered to jot down. Then there was the dream I had in which a snatched photo of the Trump-puff briefing notes of the former White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany revealed a single page, blank but for a spooky occult sigil and a caricature of mid-1960s Lennon and McCartney.

Even in our era of virulent culture wars, the Beatles still hold sway. Everybody sees or hears something specific in them – a plot, an angle, a hook – and somehow their popular appeal is never exhausted. Elevated from working-class predestiny to cultural omnipresence, the Beatles have infiltrated successive waves of postwar history, their music scattered through the grain of our lives. This is a key difference between the Beatles and the Stones, their only rivals for the zeitgeist: your own five-string heart may secretly favour the latter for their noise and front and ragged song, but they simply don’t occupy the same mossy glade in the public’s heart. The Stones lounged inside their own rarefied bubble; the Beatles were more inclusively imperfect. They are like common land, unfenced. Certain moods, memories or occasions are automatically associated with one Beatles song or another, just as some of their tracks seem to summon up what César Aira called ‘small allusive folklores’: ‘It could be a leaf falling from a tree, the blast of a car horn, some children playing ball in the plaza, the colour of the sky at dawn.’ (Off the top of my head, a song for each of his four examples: ‘Mother Nature’s Son’, ‘A Day in the Life’, ‘Penny Lane’, ‘Good Day Sunshine’.)

Mick ’n’ Keith have always been favoured by impersonators – from the 1970s TV fixtures Freddie Starr and Mike Yarwood ‘doing a Jagger’ to Stella Street and Pirates of the Caribbean – in a way the Beatles never were, perhaps because it always felt as if they were an indivisible four-headed entity. The sign outside the pub at the end of my road (which, before Covid, hosted a broad range of acts) features a cartoon of the Beatles in matching collarless suits. You can’t quite picture the Stones equivalent. Think, too, of the enormous slice of the Beatles songbook covered by other acts. How many Jagger/Richards cover versions can you call up before your forehead starts to wrinkle? The only two that came unbidden to my mind are by Devo and Cat Power, who gave us wildly different takes on ‘Satisfaction’. (For the record, my own favourite Beatles covers are, in no particular order, by Caetano Veloso, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Harry Nilsson, Bobbie Gentry – and Marvin Gaye, who turns ‘Yesterday’, a song I could never really take, into something close to a hymn. ‘I ain’t half the man I used to be, no/There’s a heavy, heavy shadow hanging over me …’)

You could compile a list of Beatles memorabilia, and track its creep in status from mass-produced fad-tat to mnemonic scraps auctioned at Sotheby’s for scarcely credible amounts of money. Things signed, or merely once brushed by a Beatle fingertip. Stubs, picks and napkins. A secular reliquary of yellowing molars and brittle locks of hair. Beatles apocrypha, too, have extended lives, fetching up even now on the wilder (or dopier) shores of academia: a queasy mix of conspiracy theory, urban legend, pop totemism. There is now a small world of serious study devoted to the Paul Is Dead phenomenon. This began in the late 1960s as a rumour that Paul McCartney had been killed in a car crash on 9 November 1966 and replaced by a flawless lookalike. (MI5 were said to have been involved …) What began as a stoner prank took on a demented life of its own. Phantoms, fakes, winks and clues. Prophetic voices, backwards-masked by unseen hands. Off-the-cuff songs revealed to be strange palimpsestic allegories, written on vinyl. The Second Oswald and the Other Paul were seen hoisting sundowners together in Rio – or was it a joint in Rendlesham Forest? The long-haired freak who shoots up Coca-Cola in ‘Come Together’ is, of course, Howard Hughes. And did you ever notice that the famous Abbey Road cover shot is centred around a vanishing point?

Again, it’s hard to think of anything comparable involving the Stones. There is a certain amount of minor-key keening around the ‘mysterious’ death of Brian Jones, but that story circulates very much as a cautionary tale rather than an airy fable, all too humanly squalid, with nothing mythic or fantastical about it. (Even a lowlife encyclopedist like myself emerges from any time spent reading about Jones wishing I knew less, not more.) The Beatles mythos, it seems, allows for an almost infinite range of speculations, parodies, retakes. Indeed, very little blue sky separates some of the more humourless readings from some of the sillier gags. In Eric Idle’s Rutles mockumentary All You Need Is Cash (1978), it’s the George-like Stig who is supposed to have died (and been replaced by a wax model), his own mysterious extinction signalled by the fact he’s not wearing any trousers on the sleeve of Shabby Road. The whole Paul Is Dead business may be preposterous, but it does confirm one reliable truth: whoever writes about the Beatles ends up producing a fable very much in their own image.

In June 1961, the Mancunian polymath Anthony Burgess and his first wife, Lynne, took a holiday in the USSR. In Cold War Leningrad there were echoes for Burgess of his backstreet Manchester childhood. The music of accents: voices that were exotic yet strangely familiar, a chorus of hard-tongued chatter he would later turn into a novel (or two, or three). Back in the UK, a fizzy excitement was in the air: a new configuration of image, music and sex crying out to be processed, though it wasn’t clear that Burgess, approaching middle age, was the one to do it. This time it would be the young instructing the old about the emergent pop-life menu of consumerist pizazz and peacock fashion: Vespa scooters and Coca-Cola bottles; book reviews in the Listener superseded by voting paddles on Juke Box Jury; Lyons Corner Houses replaced by Wimpy Bars. Burgess – lower middle-class, northern Catholic, sharply attuned to the snobberies of a cultural establishment which regarded his magpie energy with mealy Oxbridge suspicion – was appalled by the new dispensation, yet palpably energised by its noisy mischief-making.

As well as being a novelist, reviewer, piano player, composer, screenwriter and TV personality, Burgess was also something of an amateur theologian. In an interview for French TV in 1973 (conducted in French, bien sûr), around the time Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of A Clockwork Orange was released, Burgess refers to his novel, half dismissively, as something of a ‘jeu d’esprit’. But only half dismissively: the novel was, he says, ‘also a little theological discussion on the importance of free will’. It can still come as something of a shock to remember that A Clockwork Orange was originally published in 1962 (coincidentally the same year as the Beatles’ debut single, ‘Love Me Do’).* It’s a cusp text, inhabiting the same moment as Marshall McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy, with its fledgling notions of cultural studies and ‘media ecology’. Burgess gave the idiomatic gang-speak used by his moody droogs the Russian word for ‘teen’: nadsat. He was surfing the wave of a nascent global youth-speak: Soviet shrug and American lip and British cheek. At a time when the buzzwords were angst and zeitgeist and mutually assured destruction, maybe it’s understandable that people were suddenly so taken with a word like ‘fab’. (It first appeared circa 1957 and became attached to the Beatles around 1963.)

In Marcus Collins’s The Beatles and Sixties Britain, Burgess is one of a long list of mainstream commentators (variously Grub or Fleet Street, middlebrow or mandarin) whose reaction to the Beatles was somewhere between a fit of the vapours and fear of imminent apocalypse. These tweedy, clubbable, Leavisite chaps don’t seem to have noticed that their characterisation of young female Beatles fans as a deplorable case of collective hysteria might apply equally well to their own massed squeals of horror. Tartly dismissive of the whole phenomenon, they were nonetheless eager to persuade readers that the Beatles represented the end of everything good and decent and civilised and true. And of course by taking on the new pop culture, they only helped spread its contagion.

Buried in all the snobisme were occasional glints of patronising enthusiasm. ‘If a person likes the Beatles,’ Benjamin Britten said in an interview for Radio Finland in 1965, ‘it doesn’t by any means preclude their love of Beethoven.’ The Sunday Times critic Richard ‘Dicky’ Buckle called them ‘the greatest composers since Beethoven’. (Why were they always stacked up against Beethoven, pro or contra? Was it that nominative ‘Beet’?) What distinguishes Burgess’s anti-Fabs antipathy is that it feels, even at this remove, so visceral and unyielding. He dismisses the Beatles as not worthy of considered analysis, yet seems inflamed by their very existence. A personal, unassuageable demon seems to be speaking. ‘Burgess’s loathing of the Beatles continued long after they disbanded,’ Craig Brown writes. ‘As he grew older, Burgess prayed that there would be a special circle of hell set aside for the Beatles.’ In a theological inflection of the aversion therapy scene from A Clockwork Orange, he imagined all four Fabs strapped to ‘a white-hot turntable (45 rpm for ever and ever) stuck all over with blunt and rusty acoustic needles, each tooth hollowed to the raw nerve and filled with a micro-transistor (32 pop stations blaring through all eternity 32 worn flip-sides into their sinuses)’.

Burgess was sensitive to the petty resentments of an establishment he believed was ranged against him, but that didn’t staunch his own cultural elitism when it came to anything outside the canon. He liked to paint himself an enthusiast for the popular culture of the good old days – music halls, backstreet pubs, honest calorific grub – but was grumpy at the prospect of the rave new world represented by the Beatles. My guess? Burgess saw himself as a composer as much as an author, but during his lifetime received zero serious appreciation for his musical works. And now here were these four moptop yobbos rewarded with the world’s ear! In the photo appended to Brown’s chapter on Burgess the maestro is alone at a stand-up pub piano, chairs stacked up around him, a cigarette dangling from his lips. He is playing a song for no one; all the punters are elsewhere.

There may be another key to Burgess’s abhorrence of the embryonic youth culture of the 1960s and the Beatles in particular. A thoroughgoing literary and musical man, he doesn’t seem to have been especially interested in the visual arts. He inhabited a Gutenberg world of books pages in small magazines. The advent of the Beatles presaged not just the amplified catharsis of rock, but a whole new visual culture: extravagantly art-directed movies and album sleeves, clever fashion and advertising photography (which focused a new kind of erotic attention on young men), not to mention the tentacular influence of drugs, LSD in particular. Between Burgess’s voyage on the Baltic Line in 1961 and ‘Back in the USSR’ opening the White Album in 1968, there were several waves of convulsive change. Here is just one yardstick: in 1960 the future director Nicolas Roeg worked on a film called Jazz Boat, starring Anthony Newley, Bernie Winters and the Ted Heath Orchestra; he was also the cinematographer on Just for Fun (1963), whose cast comprises, inter alia, Jimmy Savile, Dick Emery, Joe Brown and the Bruvvers, and Kenny Lynch. Yet just five years later Roeg would be co-directing the cut-up saturnalia of Performance: a ripely ambisexual Mick Jagger; hints of queer S&M; a breakfast of hallucinogenic mushrooms; 99 swirls of synthesiser hypnosis; and a proto-rap protest song called ‘Wake Up, Niggers!’ The revolution would not be televised, but you might just viddy it on the big screen.

It wasn’t just a wrinkly establishment that got uppity about the Beatles. Pious left-wing critics of the time, logged in great (and very entertaining) detail by Marcus Collins, abjured Beatle pop because it didn’t show its ‘roots’ in the approved manner.† These critics favoured folk and jazz, seeing them as authentic expressions of race and class, pain and protest. The Beatles’s new pop tone was contra such ideological verities. They were young men, but didn’t seem bullish or angry enough. They were Northern working-class, but too obviously in thrall to skittish American optimism and the consolations of love. This was evidently some new kind of troubadour.

A small irony here is that the Beatles were originally allowed to play the Cavern Club only because their changeling music – freewheeling skiffle morphing into nerve-jangling rock ’n’ roll – came across as a ticks-the-boxes jazz blues offshoot. The Cavern itself was originally inspired by a jazz boîte in a Parisian cellar, its opening act a local outfit named the Merseysippi Jazz Band. Lennon, McCartney and Harrison first played together in a skiffle group named the Quarrymen. The image of pale young English boys singing lyrics like ‘Jump Down Turn Around (Pick a Bale of Cotton)’ and ‘Alabamy Bound’ may seem risible to us now, but skiffle was as good a way as any back then of thinking outside your own little parish. With its breathless rhythm and deployment of DIY instruments like washboard percussion and tea-chest bass, it had a touch of punk-ish bricolage about it. Today, such white-boy role play might be dismissed as ‘cultural appropriation’, but these callow blues were far from straightforward. This music was above all a means of locating yourself somewhere other, escaping the bounds of class inertia.

The kind of music favoured by the left was performed by and aimed at adults, not at the newly emerging teenager caste, and could leave you feeling that class was a done deal, preordained, inescapable. It might leave you feeling you were old before you were born. The leftists missed the dialectic at work here: black American blues, straitened by a life of privation; young white teens, hungry for life. The synthesis was beat music. Skiffle kids like Lennon and McCartney took this faraway folk music and used it to jemmy open things previously unexamined in their own non-fab lives. This was song – or a kind of imitative, reverberant shouting on the way to song – as a way of uncovering new ways to think and live.

None of this, though, quite explains the tonal and lyrical range soon evinced by the Beatles. There may be an element here of sub rosa (and sublimated) mourning: John and Paul both lost their mothers during their Liverpool adolescence. Half-forgotten memories processed via wistful sonic reverie: grey suburban skies, locked shops, Oedipal fog. Inside the hermetic utopia of the modern recording studio, they re-dreamed their lost home town and alchemised a new kind of urban folk music: ‘You know I work all day/to get you money to buy you things …’ Despite their happy-go-lucky image, such transitional songs already brush against a radiant skein of melancholy that would bloom in their later work.

A grasp of what might be conjured through carefully stacked or mingled tones is what their producer, George Martin, gave them. Martin’s own sense of sonic possibility was honed through the bafflingly eclectic series of projects that made up his EMI apprenticeship: from Flanders and Swann to Nellie the Elephant, from the Vipers Skiffle Group to ‘Time Beat’ by the pseudonymous Ray Cathode. His real breakthrough came on studio productions for the likes of the Goons, Charlie Drake, Bernard Cribbins, Beyond the Fringe. Here were comedy records you might want to play more than twice, on which the judicious use of montaged sound effects conjures a believable 3D landscape, where voices scrabble, loom, disappear. Martin’s way with sound could transform any pro-forma skit into a work of spaced-out pop surrealism. This ability to mute or exaggerate the speaking (or singing) ‘I’ seems especially pertinent now that we know more about the private agonies or blankness of performers like Cook, Sellers and Milligan. Not to mention Martin himself: for all that he presented himself like a character out of Waugh’s Sword of Honour, this was not his class inheritance but a persona carefully pieced together over the years, as if on a multi-track console.

There’s a clip you can easily find of the Beatles being interviewed by a venerable BBC correspondent in the lead-up to their Royal Variety Performance in November 1963. In perfect RP, cut glass tones, apparently without irony, he asks the question of the moment: ‘Are you going to lose some of your Liverpool dialect for the Royal Variety Show?’ As one, John and Paul shoot back a barrage of stage Northerner – ‘We doant all speak laak that, do we? … Bah goom, up North’ – then instantaneously switch into a parody of an upper-class accent: ‘Thank you very much. Jolly good …’ It’s Monty Python before the fact, except Merseyside rather than Oxbridge: class war conducted as cheeky badinage.

Yet, leaf through any Beatles scrapbook and you realise how many of the most celebrated images are commemorations of London: from the cover of their debut album, Please Please Me (Angus McBean’s stairwell photo taken at EMI’s London HQ) to their Savile Row rooftop gig in January 1969, from Lennon’s naughty schoolboy grin at that Royal Variety Performance in 1963 to the NW8 cover shot of Abbey Road. In later years, only McCartney maintained anything like a genuine relationship with Liverpool. Ringo Starr, after making some ill-advised remarks in 2008 (Did he miss anything about Liverpool? ‘Er … no’), was pretty much un-Scousered. The commerce between the four Beatles and Liverpool has never been straightforward. A study in 2016 estimated that Beatles tourism brought Liverpool £81.9 million a year, supporting 2335 jobs. Howard Sounes, in his biography FAB: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney (2010), dates the advent of Beatles tourism to Lennon’s death in 1980; previously, the ‘civic leaders of Liverpool had … ignored the Beatles.’ He quotes Lennon’s college friend Bill Harry: ‘Liverpool refused to do a Beatles statue. They refused to have Beatles streets named after them. Liverpool councillors [said], “The Beatles, we don’t want to know them, they were drug addicts … they brought shame to the city. We don’t want to have anything to do with the Beatles.”’

Now we have the cloistral world of National Trust tours, in which ageing fans line up to inspect the modest childhood homes of Lennon and McCartney. In reality (if ‘reality’ is really the word), few of the household objects to be found there are original: these shrines have been retrospectively set-dressed with the ‘correct’ double drainer sinks, tins of condensed milk and jars of pickled onions. This is a theatre of memory verging on the absurd, in which Yoko Ono tussles with the National Trust over the colour of John Lennon’s childhood bedspread: ‘It was definitely not pink. You know what? I remember John telling me it was green.’ It’s as if the more globalised everything becomes, the more microscopically we gaze on vanished local landscapes; the more we live online, the more we fetishise traces of the predigital world. All the Beatles’ early lives in Liverpool are obsessively recollected in numerous books, as if by some Fabs-mad Funes the Memorious: the precise layout of suburban back gardens, the correct temperature in long-ago parlours, tinny echoes in old air-raid shelters. Consulting these works can leave you with the discomfiting feeling that you know the Beatles’ childhoods in far clearer, more vivid detail than your own.

American rhythms jolted them awake, but it was in Germany that the Beatles truly learned how to play. The Reeperbahn area of Hamburg in the early 1960s was a humid mixture of postwar German efficiency and red-light anything goes. Contracted to play all night and half of the day, the Beatles couldn’t help but become more professional, even if their onstage demeanour remained spotty and unpredictable. Hamburg was both art school and chitlin circuit in one riotously sleazy transplant. (In a scene from John le Carré’s Smiley’s People, the eternal Englishman Smiley, patiently folding back layers of the past in order to clarify present perplexity, finds himself in Hamburg, at the sex club of one Claus Kretzschmar, a xerox of the kind of burly yet benevolent patron who first booked the Beatles.) As Spencer Leigh remarks in ‘The Beatles on the Reeperbahn’, his essay in The Beatles in Context, ‘Liverpool and Hamburg were of a similar size, populated with proud residents who regarded themselves as somehow separate from the rest of the country. Both cities were ports …’ Hamburg was Liverpool plus and Liverpool minus: Liverpool plus permission and permissiveness; Liverpool minus parents, class, Catholicism. In Hamburg the Beatles met a group of German art students (notably Astrid Kirchherr and Klaus Voormann) who had picked up things in Paris about the praxis of fashion. They called themselves ‘exis’ – existentialists – and their casual Left Bank aesthetic gave the Beatles their first real model of visual presentation and flair. Hamburg, like Liverpool, now hosts tours of Beatles stomping grounds during their two residencies there. What exactly are the Beatles tourists paying to see? Levelled clubs and gentrified sleaze. The long-faded tang of amphetamine sweat, professional sex, cold vomit on Sunday morning cobbles. Inspecting today’s gutter, hoping to find the faint glow of long extinct stars. Between phantom clip joints in Hamburg and a serially ‘re-sited’ Cavern Club in Liverpool, these are two cities twinned in street-level simulation.

There are now, worldwide, more than a thousand Beatles tribute acts. They spring up everywhere, from Guatemala to Hungary, Serbia to Switzerland. One act has branched out into its own ‘post-break up’ solo Beatle tribute acts; another, from Brazil, is set to open its own Cavern Club in São Paolo. Beatles tourism belongs to the post-1990s world of arts-led ‘regeneration’ and site-specific ‘rebranding’ we now inhabit. Maybe there’s a round-the-houses evocation of postwar working-class life at work, in which a specific Beatles moment – a kind of Brylcreem’d factory-boy version of Brideshead Revisited – is taken as a window onto the vanished world of old Labour, community solidarity, the 1944 Education Act, the 1946 National Health Act, maybe even the lost dream of EEC harmony. But a more apt TV analogue would be Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads, with the flinty, sarcastic Terry and the more emollient, more sentimental Bob as obvious stand-ins for Lennon and McCartney. Black and white beginnings superseded by mid-1960s colour: Bob’s sudden beard and flowing purple cravat, Terry lamenting that his army stretch in Germany exiled him from the spoils of the new permissive society. If you find the comparison a bit of a reach, recall the episode from 1973 called ‘Storm in a Tea Chest’, in which it’s revealed that Bob and Terry once played in their very own skiffle group, Rob Ferris and the Wildcats.

The Likely Lads shift from a monochrome world of apprentice labour and all-bloke pubs into a new realm of BBC2 colour, dinner parties on the Elm Lodge housing estate and ski holidays in Europe. Which calls to mind the difference between the two mid-1960s Beatles films, A Hard Day’s Night and Help! The first, shot by Richard Lester in black and white, teeters on the edge of what we now call ‘auto-fiction’: a long day’s train journey North to South, from Liverpool to a shiny London TV studio. Scripted by Alun Owen, based on his eavesdropping of the Beatles’ everyday banter (‘Look, he’s reading the Queen!’ – cut to Ringo, leafing through the house magazine of the Chelsea Set), it’s a real marvel of a film, which still bursts off the screen: fresh, feisty, with odd moments of lush downtime melancholy. Yet just a year later the Hard Day’s Night world of sooty railway concourses and stagnant canals was left far behind for Help!, which transplanted the Beatles into a witless James Bond parody that had little to do with anything in their lives. David Melbye, in his contribution to The Beatles in Context, argues persuasively that we too often have a ‘tendency to see before we listen’, and that ‘what impelled (and impels) the world to put a precedent on looking at the Beatles is what increasingly got the better of them.’ Once they stopped touring for good in 1966, film and TV specials remained the sole mode to facilitate such ‘looking’. The paradox being that the moment they stopped touring the world was, in a sense, when they truly began to conquer it. The unprecedented global hook-up of their TV performance of ‘All You Need Is Love’ in June 1967 played to an audience of more than 400 million.

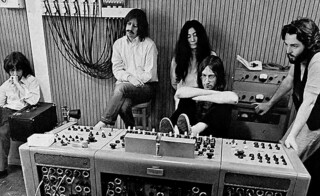

Having been perky puppets on a stage, the Beatles abruptly evaporated into studio air, becoming disembodied sonic magicians. They’d become tired of the slog of touring, press conferences, the screaming audiences drowning out their PA systems. As if the recording process itself were a form of LSD experiment, they now moved inside a subatomic landscape of sound. The conjoined signature ‘Lennon/McCartney’ has become an emblem of masterful lyric writing, but for me it’s most of all the Beatles sound that echoes down the years: the stuttering heartbeat of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’; the blissful enveloping chime of ‘Rain’; ‘Helter Skelter’, with its funhouse mirror top and Chieftain tank bottom, and the way ‘Dear Prudence’ seems actually to shine, like morning sunlight refracted through silver leaves.

At a certain point in the 1960s the Beatles became a resource virtually anyone might latch onto and exploit in their own peculiar way: all the parasitic chancers and crackpots who spotted a little niche for themselves in the folds and creases of Beatle life. Political hucksters and metaphysical hustlers; bean diet propagandists, head drillers, motorcycle nomads. This is one of Craig Brown’s recurring themes, resulting in a Beatles book in which the Beatles themselves are, in a sense, secondary characters, while everyone ranged around them comes into clearer focus: characters and situations which, put in a novel, would seem beyond belief.

As in his wonderful Ma’am Darling (a collagist’s journey around Princess Margaret), Brown deploys seemingly throwaway footnotes as peepholes into history. All the expected players are here – Bob Dylan, the Stones, Phil Spector – but also the Duchess of Windsor, Noël Coward, Peter Stringfellow, Malcolm Sargent, Beryl Bainbridge, John Birt, Jonathan Aitken, Edward Heath et al. This isn’t just a confetti of toe-curling names. Brown catches a moment when discrete segments of society were slowly coalescing into an entity called the Media. A living collage in which all such names were raised (or reduced?) to the same relative value. It’s like a B-list equivalent of the Sgt Pepper’s sleeve: George Foreman, Penelope Keith, Wayne Sleep and Jackie Stewart all choose ‘All You Need Is Love’ on Desert Island Discs; Malcolm Muggeridge and the Maharishi Yogi preen and worship, worship and preen in the same Fabs-scented air.

Brown is best known as a master parodist, ventriloquising the voices of public figures. You might expect a bit of Private Eye flippancy or spite, but the predominant tone here is harder to pin down: both more human and more spectral, at times unnervingly open-hearted. Perhaps the satirist has to have a degree of empathy for his targets, if not outright sympathy. This comes through especially in encounters with a whole subset of characters who end up stuck inside (or outside) Beatle time. The drummer Jimmie Nicol, for instance, who toured with the Beatles in summer 1964 when Ringo was briefly indisposed: Copenhagen, Hong Kong, Sydney, Melbourne – and then straight back home to his old life again. His ex-wife thinks he never recovered from his ten days as a Beatle: ‘Maybe his whole life has been frustrating, from being the Fifth Beatle. I think it affected his mental health.’

It’s Brian Epstein who is finally the most haunting figure in this regard. At the end of One Two Three Four, Brown arranges Epstein’s days and nights in reverse order, from his melancholy death in 1967, aged just 32, back to that eureka moment in the Cavern Club, which is where we came in. Epstein is a far more vivid presence here than, say, George Harrison or Ringo Starr – who seem, if anything, even more opaque than usual. With any other Beatles book, the fact that we don’t finish it with any deeper sense of John, Paul, George or Ringo might be considered a failing, but Brown’s more prismatic approach brings unexpected rewards. His book is partly about the way people come together, then ultimately snap or drift apart. Little hurrahs of social good fortune or knots of malign coincidence; the way friends and relationships can bring out the best or worst in people, personal qualities that might otherwise have lain dormant, undetected, unrealised.

In a book that has cameo appearances from Rolf Harris, Charles Manson and Jeffrey Archer, the only occasions on which Brown’s equanimity is disturbed involve Yoko Ono. He is exasperated by her even before she enters Beatles time, and has equally little time for today’s now rehabilitated and (mostly) revered figure. There’s no doubt that initial reactions to Yoko were shaped by a thick fug of racism and misogyny, but it’s possible to acknowledge this and at the same time share Brown’s feelings about her modus operandi. To the sceptics, she is someone who – like some members of the royal family and a certain ex-president – was born into gargantuan wealth yet can present as a world-class grifter, with a propensity for staggeringly inane media pronouncements. While her relationship with Lennon in no way ‘caused’ the break-up of the Beatles, there are things to be said about the gulf between her conceptual Artworld values and the mirror-smashing poetics of Pop. One of the reasons mainstream critics found the Beatles so aggravating was the way they casually upended so many high/low cultural hierarchies. Ono led Lennon to a place that was, arguably, the worst of both worlds. A baby food version of the avant-garde. Fuzzy political gestures lacking any real slog or engagement. Buzzword slogans that read like Mao Zedong subbed by Patience Strong. Many of the artworld ideas Ono traded in (or on) were secondhand, watered down, and very much reliant on the ossified gallery system for any spark they did generate. Whereas the Beatles stood on stage and made shapes with their bodies and detonations with their instruments and the world flew off its axis.

Brown’s temporal arc rests on this bevel: on the one hand, an airless pre-pop context in which the Beatles now appear inevitable, a sheer historical necessity; on the other, the fragile chain of loopy coincidences that actually brought them together – these four people, anything but fated to meet – in this wholly serendipitous moment. Brown’s ‘Beatles in Time’ may not quite be the pop biography equivalent of a Nic Roeg film, but there are razor edits, skewed emphases, revealing leaps of era-travel. The spine of the book is a conventional narrative, starting in Liverpool in the 1940s and ending with bitter dissolution in the 1970s, but in between, Brown balances wave and particle: each moment in its unique grain and peculiarity, yet also taking its place in a decade-long arc.

In one arresting late chapter, he considers two photographs of the band, one from 1964, the other from 1969. In the first image they’re all in a beaming row, wearing the sunny bank holiday smiles of dutiful light entertainers; in the second, they are atomised, broody, under a pall. They are showing everything time took out of them, more than equal to the time they gave. ‘Comparing these photographs, just five years apart,’ Brown writes, ‘it’s as though they have been crushed by the world’s adulation. Such talent, so many dreams, such joy – and now they just look trapped and bruised.’ My only quibble is that it wasn’t simply the world’s ‘adulation’ that crushed them so. There’s a more private aspect to consider. They had lived inside one another’s lives for a decade, these four, going from larky Liverpool lads to life-scarred, world-borne men, while doing something for which there really was no script or example or precedent.

Two final items to add to the Beatles log. The first is yet another cartoon of mid-1960s period Beatles, improbably illustrating an article on the website of a Marshall McLuhan-based think tank. The sober little sketch shows the Fab Four huddled attentively around an open tabloid, whose headline blares: I READ THE NEWS TODAY OH BOY. Here was a time, the image seems to say, when we shared more than we disavowed – so unlike our own rudely fragmented present. Even on the lip of apocalypse, might the Beatles remain one of the last things we can all agree on? Are they the no man’s land on Christmas Day, where both sides might pause, put down their weapons and have a moment’s singalong? You can almost hear the chant in ‘Hey Jude’ striking up. Laaa, la la, la-la-la laaa …

The second was a mention of the band in an article speculating on Donald Trump’s continued sway over the Republican Party. Would Trump ‘be a member of a set of Republican all-star leaders or the Republican all-star leader; one of the Beatles or the Beatle’? This surely misses the point, Beatles-wise. There is no ‘the Beatle’. I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together, the Beatles, now.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.