Nobody has a good word to say about Mabel Loomis Todd. When she’s remembered at all, it’s as a homewrecker: the vamp who seduced Emily Dickinson’s brother, Austin, 27 years her senior, and destroyed his marriage to Susan Gilbert, Emily’s closest confidante. Like any good seductress, Todd was an opportunist. She exploited Austin’s role as the treasurer of Amherst College to wangle her own husband, David, into powerful university positions and forced him to build her a Queen Anne-style house just across from his family home. After his death she conned his surviving sister, Lavinia, into deeding her some land. But, perhaps most damning of all, Emily Dickinson was hardly cold in the grave when Todd made a bid to edit her poems and ride to literary notoriety on Emily’s white apron strings. So the story goes – or a version of it.

Dickinson’s work first appeared in 1890 in a volume co-edited by Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Julie Dobrow’s After Emily attempts to rescue Todd’s reputation by offsetting her bad behaviour against the extraordinary labour she devoted to transcribing, editing and promoting Dickinson’s work. It also chronicles the trials of her daughter, Millicent Bingham. The first woman to receive a doctorate in geography from Harvard, she sacrificed her academic career to finish the editorial work her mother began. Readers may not agree with the version of Emily Dickinson they presented, or approve of the changes they made to her work, but if it hadn’t been for these two women, we might not have any Emily Dickinson at all.

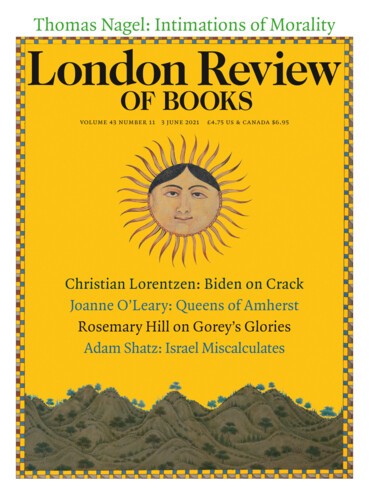

Born in Cambridge in 1856, Mabel Loomis was convinced from a young age of her own ‘all-embracing genius’. Polly Longsworth, who has edited her love letters to Austin, writes that for Mabel ‘a public parlour or dining room comprised a small stage which she learned to dominate with her conversational and artistic gifts … Adulation from adults was a sustaining element of her life.’ Her sense of entitlement was fierce – ‘bloodlines meant distinction’ and Mabel’s maternal lineage could be traced back to the Mayflower. Her parents limited her playmates to the children of Harvard professors. As an infant, she was placed in the arms of Henry David Thoreau (apparently he couldn’t tell which end of the baby was which).

In 1877, she met David Todd, a ‘blond with magnificent teeth’, who was then working in Washington alongside the distinguished astronomer Simon Newcombe. Her parents had reservations when the couple got engaged in 1878: he had no notable ancestors, save Jonathan Edwards (who was only a distant relation); his means were modest and there was a family history of mental illness. Mabel, however, found it in herself to overlook all this. Her first requirement in a husband was sympathy to her ambitions. ‘No man can make a drudge out of me,’ she told her parents. ‘There are capabilities in me, I know, which I’ve not yet begun to feel & they shall be developed & filled & [David] shall help me … I shall have full sway.’ Dobrow recounts the way David would every night ‘undress her before the fire … warm their bed with hot bricks, and then hold her close and kiss her, and how each morning he would warm her clothes and bring her figs and grapes and feed them to her’.

Shortly after their marriage in 1879, Mabel got pregnant. She thought it was impossible to conceive except ‘at the climax moment of my sensation … once passed, I believed the womb would close, and no fluid could reach the fruitful point.’ When her periods stopped, she did everything in her power to bring on the flow, including long walks, hot sitz baths. At her doctor’s suggestion she inserted belladonna and morphine in her vagina to ‘induce distension and local looseness’. Another physician dosed her with quinine – then commonly prescribed to induce abortions. No dice. Mabel was distraught, but mollified by David’s promise to provide childcare and his reassurance that she would ‘not be bound down by the low drudgery’ of motherhood.

Crucially, the sex was still good. David ‘tries to make it just what I desire in every respect’, Mabel wrote. ‘I frequently find myself singing aloud.’ She developed a notational system to keep track (she would use the same symbols to record her assignations with Austin). Full intercourse was marked as ‘f.m.’, coitus interruptus was designated as ‘o’, sexual activity of another kind went down as ‘#’, while her orgasms were recorded with a long Dickinsonian dash: ‘—’.

Millicent arrived on 5 February 1880, weighing ten pounds. Mabel didn’t take to motherhood. She was delighted that Millicent’s first word was ‘mamma’ and that her second was ‘book’, but wrote: ‘I do not in general care for children & I do not want another.’ She fretted that Millicent didn’t have a ‘handsome nose’ and was a fat baby. She was also perturbed by her lack of vivaciousness: ‘I shall be indeed distressed if she is going to be a shy child.’ Mabel thanked God for the ‘perfect restoration’ of her postpartum body. Her journals show her to be a woman who thrived on male attention: ‘I have flirted outrageously with every man I have seen’; ‘I have simply felt as if I could attract any man to any amount’; ‘What is there in me which attracts men to me, young and old? I am deeply grateful for the power, and hope I may use it for the good of those who succumb to it.’

A year after Millicent’s birth, Mabel was dealt another blow. David was offered a job teaching astronomy and directing the college observatory at Amherst College, his alma mater. (He had failed a maths exam at the US Naval Observatory in Washington, which scuppered his chances of promotion there.) Amherst, Mabel feared, was ‘too small and provincial’ for her. She was loath to leave behind the social life she had cultivated in Washington: ‘I can hardly breathe, and I am so sad!’

Despite her reservations, Amherst proved ‘quite ideal’ for Mabel, satisfying her desire for ‘refined and educated society’. Her entry into that society was assured by Austin’s wife, Susan, a prominent member of the town’s literary community who hosted salons at her fine Italianate home on Main Street. The Evergreens was ‘unlike any other’ house in Amherst, kitted out with ‘a green marble fireplace, a mechanical call bell system and an early centralised heating system from the coal-fired furnace’. Mabel was ‘captivated’ by Sue, whom she entertained by playing the ‘beautiful new upright piano’ in the Dickinsons’ drawing room (she quickly earned a reputation as the finest musician in Amherst). She didn’t lose sleep over her decision to leave Millicent in Washington with her parents. Within a month of her arrival in Amherst, the child is mentioned only occasionally in her journals. She spent about three evenings a week with the Dickinsons, who were everything to which she aspired. Things hadn’t worked out quite as she’d hoped when she first met David. In the early 1880s, the Todds were still living in boarding houses: the prospect of owning a home, which would allow them to ascend into solidly middle-class existence, seemed remote.

It wasn’t long before she was practising her ideal signature: ‘Mabel Loomis Dickinson’. Ned, the Dickinsons’ eldest son, fell for her immediately. He suffered from epilepsy, a big taboo in the 19th century, and had led a sheltered existence. Sue encouraged the relationship, and even postponed his 21st birthday party because Mabel was out of town: Ned was determined to have the first dance with Mrs Todd. She viewed him as a ‘knight errant’, an escort to social events when David was indisposed. ‘Indeed, I think it will not hurt Ned … that he worships the very ground I walk on,’ she wrote breezily in April 1882. Then, more ominously: ‘I could twist him around my little finger, that he would go off and kill somebody if I bade him.’ Poor Ned ambled around Amherst sporting a pussy willow that Mabel had given him in his buttonhole until the ‘fluffy blossom dried and dropped off’. But by the time he declared his love for her in September 1882, her attentions were firmly fixed on his father.

Austin and Mabel began to take long rides in the Dickinson buggy and spend time at the Homestead, where Emily lived with her sister, Lavinia, and their bedridden widowed mother. On her first visit there, in September 1882, Mabel played the piano while Austin’s mother listened from upstairs and Emily from another room. The next day, Mabel and Austin confessed their feelings for each other. Both recorded the moment in their journals with the word ‘Rubicon’. Their relationship didn’t become physical until December 1883, however, an event marked in each of their diaries with a neologism that entwined their names: ‘AMUASBTEILN’. All of this tortured Ned. He complained to his mother that Mabel was ‘an awful coquette’, who had led him on and was now doing the same to Austin. Sue kept a beady eye on Mabel after that, causing her to complain of the ‘horribly chilling’ atmosphere at the Evergreens.

From the time Austin and Mabel consummated their relationship until the Todds moved into a rented property on Lessey Street in 1885, the couple’s liaisons – about a dozen a month – took place at the Homestead. Throughout this period, Emily Dickinson managed to avoid meeting her brother’s mistress. It was not for Mabel’s want of trying. She was fascinated by the woman who had ‘not been out of her house for fifteen years’, who was called in Amherst ‘the myth’ and who wrote ‘the strangest poems’. ‘She is,’ Mabel reflected, ‘in many respects a genius.’ She began pursuing Dickinson in the autumn of 1881, when, departing for a visit to Washington, she wrote her a farewell note. Dickinson’s response: ‘The parting of those that never met, shall it be delusion, or rather an unfolding of a snare whose fruitage is later?’ Dobrow doesn’t quote these lines, but makes much of Dickinson’s hospitality to Todd. ‘Emily always rewarded Mabel’s music with small offerings: a glass of wine on a silver salver, a flower from her conservatory, a piece of cake.’ Other critics take a more cynical view, arguing that Dickinson’s response to Todd’s gifts – a painting of an Indian pipe plant, for instance, in September 1882 – was thorny. ‘I know not how to thank you,’ she wrote. ‘We do not thank the Rainbow, although its Trophy is a snare.’

The lovers’ assignations usually took place in the dining room (where Dickinson had a second writing desk) or in the library (through which she had to pass to get to the conservatory, where she spent much of her time). In her rollicking Lives like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and Her Family’s Feuds (2010), Lyndall Gordon suggests that Emily would not have taken well to being excluded from areas of her own house for hours at a time while her brother and his mistress did God knows what behind closed doors. Lavinia, on the other hand, quickly became an accomplice, often passing letters between Austin and Mabel – as did David, who actively encouraged the affair. For him, the benefits were twofold. Austin used his influence at Amherst College to further David’s career. Within a year of taking up his post, he was promoted to associate professor and given a large increase in salary. Mabel’s adultery also gave David licence to indulge in philandering of his own. She was tolerant of this (often arranging liaisons for her husband) so long as the women weren’t of ‘low’ breeding. ‘I do not think David is what might be called a monogamous animal,’ she wrote. Sue, ignorant of the arrangement, thought Mabel’s husband pathetic: ‘Little dud David’, she called him.

In 1885, Mabel and Austin put the newfound privacy afforded by the Todds’ house on Lessey Street to good use. Both engaged in cringeworthy postcoital record-keeping. Austin adopted Mabel’s habits of notation; his symbol for intercourse was ‘==’. On 3 January 1886, he notes ‘at the other house 3 to 5 and + =====’. Mabel’s diary from that day records ‘a most exquisitely happy and satisfactory two hours’ of sex by the living-room fire. Ten times in 1886, Austin’s parallel lines are accompanied by the words ‘with a witness’. Longsworth suggests that this was David – who, she alleges, often played voyeur. Dobrow wonders whether it might be a reference to Millicent, now living with her parents. But it seems unlikely that Austin would have bothered to record the presence of a six-year-old. Later in life, Millicent reflected that she had always seemed beneath Mr Dickinson’s notice. ‘Hello, child’ were the only words he ever uttered. ‘Then he would lead Mamma upstairs while she murmured “my King!”’

Whatever the extent of his voyeurism, David was happy to give the couple space. When he knew Austin and Mabel were alone together, he signalled his return by whistling a tune from the opera Martha. Sue was less complaisant. During a row with Austin in January 1885, she ripped the wallpaper from the hall at the Evergreens. Ned felt his mother’s pain. ‘Such superhuman efforts to keep up & cheerful, for those around her, mortal eye never witnessed,’ he wrote to his sister, Mattie, who was away at school. ‘I would willingly lay down my life for her.’

Mabel now frequently fantasised about the death of her former mentor. She was increasingly scornful of Sue’s ‘low’ background: her father had been a ‘common farmer’, a tavern owner and a drunk. (Austin, she noted, has ‘begun to feel … that it does not do for persons of entirely different social grade to marry’.) After her younger son, Gib, died of typhoid fever in 1883, Sue spent a prolonged period in mourning dress, which led Mabel and Austin to refer to her as the ‘incubus’ and ‘the great big black Mogul’. Mabel recorded her lover’s ‘revelations’ about his wife and placed them in an envelope labelled ‘Austin’s statements to me’. She wrote that Sue’s ‘morbid dread of having children has hurt & distressed [Austin’s] life to the quick. She caused three or four to be artificially removed before Ned. And she did everything in her power to rid herself of him – to which efforts all his ill-health is attributed.’ (Her own efforts to abort Millicent were forgotten.) According to Mabel, Sue had once thrown a carving knife at Austin. Her ‘fits of horrible & entirely unrestrained temper have put [him] several times in danger of his life & he says if anything should happen to him suddenly we may be tolerably sure she has killed him’.

Mabel begged Austin to write down these allegations, hoping they would act as an ‘insurance policy’ if anything were to happen to him. He repeatedly promised to do so and then backed out. Take this letter from 1884:

Yes, my darling, I did promise you that sometime I would put into your hands the story of my life to use as a shield, if ever, when I am not here to answer for myself, any attack should be made upon my love for you, or yours for me, or our relations to each other. And yet is it not better and nobler that I say nothing which involves any other, reflects upon any other! … Is it not better to begin with my meeting you and for the first time feeling clear sunshine!

Mabel sought alternative insurance policies. A home of her own – on part of the Dickinson meadow – would be a start. In 1885, she spent the summer in Europe. ‘Dear heart,’ she wrote to Austin from Switzerland on 3 August, ‘I do so hope things will be pleasantly arranged for me when I get back. I am really thinking a good deal about a house … I suppose nothing especial has been done about it yet.’ The trouble was this: to deed a plot of land to Mabel, Austin needed the signature of his sisters, co-heirs to the family estate. Lavinia was no obstacle, but Emily was a different matter. Mabel continued to try to reel her in. Emily responded to one of her letters from Europe with grudging acidity: ‘Will Brother and Sister’s dear friend accept my tardy devotion?’ Around the same time, Emily wrote to Ned, promising to protect his inheritance from the paws of Austin’s mistress: ‘No Treason,’ she promised her nephew. ‘Ever be sure of me, Lad.’

Mabel had to wait for her plot until after Dickinson’s death in May 1886. Contractors were standing by a month later. Mabel’s ‘little house of thirteen rooms’ with a ‘geometric design’ was completed by the end of the year. She painted it red so it stuck out like a sore thumb on the Dickinson meadow. It was named the Dell at Austin’s suggestion. He had arranged for the house to have a back staircase which offered discreet access to the second storey, where he and Mabel would spend evenings together ‘by the upstairs fire’. The Dell was the first, and perhaps the smallest, way in which Dickinson’s death would change the Todds’ lives for good.

It makes sense, therefore, that Dobrow begins with a snapshot from 19 May 1886, the day of Dickinson’s funeral. But the close third person in which she writes is excruciating. Here is her first sentence: ‘Mabel Loomis Todd stared unhappily out the window, her eyes filled with tears.’ We look on as Mabel styles ‘her light brown hair into a series of upsweeps’, as she scrutinises ‘the small worry lines’ that mark ‘her otherwise smooth porcelain skin’. We watch her ‘walking carefully down the stairs in a pair of high-heeled shoes’. We’re told that she chose her dress carefully, opting for something simple, in the knowledge that soon ‘she would be among the Dickinson family … and that she would see the woman whom she often referred to in her diaries and journals as “my dear friend, Miss Emily Dickinson”’. And yet something about the writing captures the farce of the thing itself. Mabel was shunned for the ‘extreme grief she so publicly displayed for a woman she had never met face to face’. No matter. Here, suddenly, was Austin’s sister – or, rather, her corpse: ‘Emily Dickinson lay dead in her white coffin, a little bunch of violets along with one pink cypripedium around her neck.’ Emily may have successfully eluded her for five years, but Mabel, quite literally, pursued her to the grave. Sue Dickinson didn’t attend the funeral, unable to bear the thought of standing in Mabel’s presence.

Emily Dickinson loved to flee. Long before the Todds arrived in Amherst, years before her withdrawal from society became almost absolute, she devised elaborate ways of avoiding people, a habit her family referred to as ‘elfing it’. When she was sent to deliver a letter, she would ring the doorbell and leg it; she greeted family guests with what she called ‘sorry grace’ and played the piano grudgingly – and only if visitors remained in an adjoining room. She avoided chores like the plague – ‘God keep me from what they call households’ – and left the burden of domestic toil to her mother and sister: ‘I do love to run fast,’ she said, ‘and hide away from them.’ She arrived late to church to escape small talk. Here she is in 1853, boasting to Sue of successfully evading the congregation:

I’m just from meeting, Susie, and as I sorely feared, my ‘life’ was made a ‘victim’. I walked – I ran – I turned precarious corners – One moment I was not – then soared aloft like Phoenix, soon as the foe was by – and then anticipating an enemy again, my soiled and drooping plumage might have been seen emerging from just behind a fence, vainly endeavouring to fly once more … I smiled to think of me, and my geometry, during the journey there – It would have puzzled Euclid … How big and broad the aisle seemed, full huge enough before, as I quaked slowly up – and reached my usual seat! … [I] got out of church quite comfortably. Several roared around, and, sought to devour me … until our gate was reached. I needn’t tell you, Susie, just how I clutched the latch, and whirled the merry key, and fairly danced for joy, to find myself at home.

Note the melodrama, the lordly tone so at odds with the invisibility she has taken pains to preserve. Her prose isn’t shy, it doesn’t lie low: its presence on the page is overbearing.

Dickinson’s hide-and-seek with society was carefully staged. In 1877, she refused to see Samuel Bowles, the editor of the Springfield Daily Republican, with whom she often corresponded. ‘Emily, you damn rascal,’ he shouted from the bottom of the stairs. ‘No more of this nonsense. I’ve travelled all the way from Springfield to see you. Come down at once.’ She descended. He had called her bluff. She signed off her next letter to him ‘Your Rascal’, and added a playful postscript: ‘I have washed the Adjective.’ Her niece recalled Dickinson miming the locking of her bedroom door: ‘Mattie: Here’s freedom.’

The Soul selects her own Society –

Then – shuts the Door –

To her divine Majority –

Present no more –

The arrogance is daunting. The rest of us, like Bowles, might beat a path to her door. It was Dickinson’s prerogative to slam it shut.

Her work has a twisted peekaboo quality. The speaking voice avoids intimacy while accosting us at the same time: ‘I’m Nobody! Who are you?’ A similar irony distinguishes Dickinson’s character and that of her poems. Try to say who she was, or precisely what she meant, and person or poem will vanish from view – all that remains is the grin of the Cheshire Cat. The trouble with the ironist, Kierkegaard said, is that ‘to secure an image of him’ is impossible, ‘like trying to depict an elf wearing a hat that makes him invisible’. ‘I’m so amused at my own ubiquity,’ Dickinson wrote to Sue. ‘It mustn’t scare you if I loom up from Hindoostan, or drop from an Appenine, or peer at you suddenly from the hollow of a tree, calling myself King Charles, Sancho Panza, or Herod, King of the Jews.’

To Higginson, Dickinson was a ‘virgin recluse’; Todd ‘inevitably’ thought ‘of Miss Havisham in speaking of her’. It’s true that these early editors perpetuated the misleading image of the ‘solitary spinster’, which provoked the ire of later feminist critics such as Ellen Louise Hart and Martha Nell Smith. ‘The most marketable image of Dickinson the poet,’ they wrote in Open Me Carefully (1998), ‘was that of the eccentric, reclusive, asexual woman in white.’ But it’s equally true that Dickinson played that role well enough when it suited her. In her introductory letter to Higginson on 15 April 1862, she depicted herself as a lonely innocent: ‘Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive? … I have none to ask –’. The letter bore no signature. Instead, Dickinson wrote her name on a small card and placed it in a separate envelope enclosed within the larger one.

Her letters to Higginson feign a desire to be instructed. (As her niece put it, she enjoyed ‘playing naive’ for the ‘sheer glee of her game’.) ‘I would like to learn,’ she wrote. ‘Could you tell me how to grow – or is it unconveyed – like Melody – or Witchcraft?’ But his advice that a change of word here or there would make for a proper rhyme or a more sonorous rhythm, was, without exception, ignored. Dickinson replied to one letter in riddling deadpan: ‘You think my gait “spasmodic” – I am in danger – Sir – You think me “uncontrolled” – I have no Tribunal.’ The letter replicates the eccentricities of language Higginson wished to eradicate from her verse. And yet, maddeningly, she continued to end her letters with pleas for tutelage: ‘But will you be my preceptor, Mr Higginson?’ She fashioned herself, he later noted, as a ‘breathless child’.

He asks how long she’s been writing poems: ‘I made no verse – but one or two – until this winter – Sir –’. (She had written hundreds.) He asks if she’s read Whitman and she plays dumb: ‘I never read his Book – but was told that he was disgraceful –’. (If she hadn’t read Leaves of Grass in full, she’d certainly encountered Whitman’s work in the Atlantic and the Springfield Daily Republican.) When Higginson requests her portrait, Dickinson demurs: she is ‘the only Kangaroo among the Beauty … I am small, like the Wren … my eyes, like the Sherry in the Glass, that the Guest leaves –’. Higginson is late to the party: Dickinson has already left.

Austin remarked, late in life, that Dickinson ‘posed’ in her letters. He might have had in mind an exchange from 1851. He had suggested to his sister that she write more plainly. ‘You say you don’t comprehend me, you want a simpler style,’ she responded. ‘Gratitude indeed for all my fine philosophy! … I’ll be a little ninny – a little pussy catty, a little Red Riding Hood, I’ll wear a Bee in my Bonnet, and a Rose bud in my hair.’ It rankled that their father had thought Austin the writer among his children. In 1853, Dickinson scoffed at her brother’s attempts at verse-making: ‘Austin is a Poet, Austin writes a psalm. Out of the way, Pegasus … I’ll tell you what it is – I’ve been in the habit myself of writing some few things, and it rather appears to me that you’re getting away my patent … you’d better be somewhat careful.’

As her relationship with Higginson progressed, Dickinson’s ego showed through the childlike veneer. When he worries that her poems are beyond him, she scoffs: ‘You say “Beyond your knowledge”. You would not jest with me, because I believe you – but Preceptor – you cannot mean it? All men say “What” to me, but I thought it a fashion –’. His correspondence mattered to her because he offered a benchmark of conformity against which to push. It’s as if she wanted to arouse his expectations just to disappoint them, repeatedly rebuffing his suggestions while somehow sustaining his interest in her work.

Dickinson wrote almost 1800 poems, but only ten were published during her lifetime, and none with her explicit consent. When ‘A narrow Fellow in the Grass’ appeared in the Springfield Daily Republican in February 1866, she was outraged. (Sue had shared the poem with Bowles, who printed it anonymously.) In 1862, she had told Higginson that publication was as ‘foreign’ to her thought ‘as Firmament to Fin’. Anxious that he might identify the verse in the newspaper as hers, she explained that it was ‘robbed of me – defeated too of the third line by the punctuation … I had told you I did not print – I feared you might think me ostensible.’ She wanted Higginson to know that she had not conformed: ‘Publication – is the Auction/Of the Mind of Man –’.

Camille Paglia calls it ‘a sentimental error to think Emily Dickinson the victim of male obstructionism’; her poetry, she argues, ‘profits from the enormous disparity’ between her ‘abnormal will’ and ‘the feminine social persona to which she fell heir at birth’. I think this is true. Dickinson didn’t actively support the political campaign for women’s rights, but her poems radically subvert the patriarchal laws that governed 19th-century verse-making. What Higginson called her ‘spasmodic gait’ was a reaction against the orderliness of hymn metre, the neat rhythms of which were ripe for hobbling. (Nothing, after all, ‘oppresses, like the Heft/ Of Cathedral Tunes –’.)

Scenes of eruption – Pompeii, Etna, Vesuvius – recur throughout the poems. When she writes of ‘the ‘reticent volcano’ that confides its ‘projects’ to ‘no precarious man’, its ‘buckled lips’ poised to detonate, she could be describing her approach to form: the contraction of syntax, the way nouns collapse together, the lacerations her dashes inflict on traditional grammar, her strange use of articles and prepositions or their abandonment. In the absence of the ordinary sutures of language, ellipses prevail. For Allen Tate, the most influential critic of the 1930s, Dickinson took this too far: she ‘perceives abstraction and thinks sensation’, he wrote, but her ‘ignorance, her lack of formal intellectual training’ means ‘she cannot reason at all. She can only see.’ (Suggestiveness in place of reason can only be involuntary.) To my mind, the best description of her method comes from David Porter. In The Art of Emily Dickinson’s Early Poetry (1966), he likened it to ‘sfumato, the technique in expressionist painting whereby information … on a canvas is given only piecemeal and thereby necessarily stimulates the imaginative projection of the viewer’, who must supply the ‘missing context’.

But even those who admired Dickinson’s work have been put off by the demands she places on the reader. Denise Levertov found something chilling about her command on the page, an ugliness in her aristocratic self-assurance: ‘You know, actually those dashes bother me,’ she wrote to Robert Duncan in 1961. ‘There’s something cold and perversely smug about E.D. that has always rebuffed my feeling for individual poems … She wrote some great things – saw strangely – makes one shudder with new truths – but ever and again one feels (or I do) – “Jesus, what a bitchy little spinster.”’

The idea that there’s something ‘smug’, ‘cold’ and ‘perverse’ about the dashes is intriguing. These visual markers often represent points at which meaning vanishes. Dickinson has elfed it and – like Lavinia landed with her sister’s chores – we’re left to supply a meaning the poet hasn’t; or else to occupy a typographical void where sense evades us. The poems require an intensity of engagement that can make the reading experience border on masochism. The effect is physical: to use Levertov’s phrase, the poems ‘make one shudder’.

The shudder is a premonition of pain, a muscular response to something that hasn’t yet happened. Therefore, as Frank Kermode wrote in the LRB (13 May 2010), the shudder is ‘a highly emotional affair, deeply involved with acts of imagination’. It’s easy, he says, ‘to imagine an act of reading as accompanied by shuddering’. On their first meeting, Dickinson told Higginson that ‘if I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me I know that is poetry … if I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.’

In her own work she sometimes achieved this effect by twinning the decomposition of language with that of the physical body. Corpses and near corpses obsessed her. When Benjamin Newton, a young attorney who briefly worked with her father, died in 1854, Dickinson contacted a complete stranger, Edward Everett Hale, asking for details of Newton’s final hours. ‘You may think my desire strange,’ she wrote, but there was no one else to ‘satisfy’ her ‘inquiries’. Aged fourteen, she was led away from the bedside of a dying schoolfriend after people became disturbed by how long she had stood transfixed by Sophia Holland’s half-closed eyes. The moment has an echo in some lines from 1863:

I’ve seen a Dying Eye

Run round and round a Room –

In search of Something – as it seemed –

Then Cloudier become –

And then – obscure with Fog –

And then – be soldered down

Without disclosing what it be

’Twere blessing to have seen –

Life, as she construed it, was incarceration: ‘A single Screw of Flesh/Is all that pins the Soul.’ The game is rigged against us; the body is ‘a loaded gun’, ‘a bomb’ to ‘hold our Senses’ temporarily before the thing explodes.

Dickinson was opposed to all manner of authority, but she also craved the orthodox: without it, her poems had nothing to dismantle. Enter God. The narrative of salvation, the false promise of a tidy conclusion to life’s mess, was the prime mover behind her thought. At seventeen, she explained her refusal to become a Christian: ‘It is hard for me to give up the world.’ To subjugate the present to the promise of everlasting life – even if salvation were plausible – was, for her, a dull prospect. But she needed to keep the idea in play, just as the ghost of hymn metre had to hover behind her halting rhythms. In 1882, she wrote that it was possible to ‘believe, and disbelieve a hundred times an Hour, which keeps Believing nimble’.

Many of her poems flirt with salvation, before redefining ‘eternity’, one of her buzzwords, as nothingness:

Behind Me – dips Eternity –

Before Me – Immortality –

Myself – the Term between –

…

’Tis Kingdoms – afterward – they say –

In perfect – pauseless Monarchy –

Whose Prince – is Son of None –

‘Immortality’, the kingdom of which ‘they’ speak, is a chimera presided over by a fictional monarch: the ‘Son’ of nobody. Life is a ‘brief Drama in the flesh’, ‘the term between’ two eternities of blankness.

Her poems might briefly indulge the fantasy of living beyond: ‘I heard a Fly buzz – when I died –’. But the ever-after is evoked in order to dissolve the proposition: ‘And then the Windows failed – and then/I could not see to see –’. The dash casts us into nothingness, as it does in ‘I felt a Funeral, in my Brain’, where the corpse registers the mourners moving to and fro, and consciousness seems to transcend the decline of the body, until the last stanza:

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down –

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing – then –

The dash marks the point at which breath expires and consciousness is lost; it gestures towards the future that will never arrive. It’s a typographic shudder.

‘Dickinson loved Christ but jilted Him and married Death,’ Charles Olson wrote in 1947. ‘Her stretch and yawn for the grave strained her nature, poisoned it.’ The observation is correct, but the slur misjudged. As in Tate’s presumption that Dickinson was incapable of reason, Olson assumes some failure on her part. In fact, as she wrote in 1859: ‘I like poison very well.’ In 1848, a letter of Austin’s finds the 17-year-old Emily ‘engrossed in the history of Sulphuric Acid!!!!!’ At home, she took relish in drowning four ‘superfluous’ kittens in pickle brine (a shortcut to taxidermy).

Dickinson was selfish, nasty and emotionally impaired, but took pride in it: ‘I love to be surly – and muggy – and cross.’ In 1850, when her uncle Joel Norcross broke his promise to write to her, Dickinson sent him a vicious letter: ‘I shall kill you – and you may dispose of your affairs with that end in view. You can take Chloroform if you like – and I will put you beyond the reach of pain in a twinkling.’ Lavinia said her sister could be ‘savage’. Samuel Bowles came to see her as ‘half angel, half demon’. His wife, Mary, found her manner ‘alarming’. Dickinson exploited this anxiety with glee and, when Bowles was out of town, took the opportunity to bombard Mary with menacing pleas for attention. In March 1862, shortly after Mrs Bowles had given birth, Dickinson wrote:

Could you leave ‘Charlie’ – long enough? Have you time for me? … I send a Rose – for his small hands. Put it in – when he goes to sleep – and then he will dream of Emily – and when you bring him to Amherst – we shall be ‘old friends’ … Don’t love him so well – you know – as to forget us – We shall wish he wasn’t there – if you do – I’m afraid – shant we? … You won’t forget my little note – tomorrow – in the mail – It will be the first one – you ever wrote me – in your life – and yet – was I the little friend – a long time? Was I – Mary?

To a woman haunted by a series of stillbirths, and uncomfortable about her husband’s intense correspondence with Emily, this was downright cruel.

Dickinson enjoyed her own suffering too: ‘A nearness to Tremendousness –/An Agony procures.’ Contentment, she feared, would dull the senses. The greatest constraint she imposed on herself was solitude: ‘Don’t you know you are happiest while I withhold,’ she wrote to Judge Lord in 1878, ‘don’t you know that “No” is the wildest word we consign to language.’ Writing to Austin in 1863, Bowles sent his best to Dickinson with a hint of snark: ‘to the Queen Recluse my especial sympathy – that she has “overcome the world” –’. A poem she wrote that same year says it all:

It might be lonelier

Without the Loneliness –

I’m so accustomed to my Fate –

Perhaps the Other – Peace –Would interrupt the Dark –

And crowd the little Room –

Too scant – by Cubits – to contain

The Sacrament – of Him –

I am not used to Hope –

It might intrude upon –

Its sweet parade – blaspheme the place –

Ordained to Suffering –

It might be easier

To fail – with Land in Sight –

Than gain – My Blue Peninsula –

To perish – of Delight –

Solitude allows us to inhabit any number of imaginary selves; society demands a single, recognisable identity, to hold our character constant. This, Dickinson feared, would render her negatively incapable, killing off her capacity to call forth the shudder. ‘If I stopped to think of the figure I was cutting,’ she wrote to Sue, ‘it would be the last of me.’ Asked about her unorthodox use of pronouns, she answered: ‘When I state myself, as the Representative of the Verse – it does not mean – me – but a supposed person.’ It’s a comment on her character as well as her poems: ‘How dreary – to be – Somebody!/How public – like a Frog –’.

She deplored certainty: ‘A Doubt if it be Us/Assists the staggering Mind –’. She was a poet of second thoughts, as her manuscripts – even the cleanest of them rife with deletions, insertions, variants and marginalia – attest. The radical uncertainty that characterises her writing, and the mysteriousness of her life, make the feuds, the lawsuits, the general carnage that ensued after her death seem inevitable.

Shortly after Emily died in 1886, Lavinia Dickinson began to sort through her sister’s effects. She had, at Emily’s request, already burned hundreds of letters when she opened a locked bureau drawer and found what she recognised to be poems: hundreds of sheets of stationery paper stitched into booklets. She soon uncovered more writing: on loose leaves of paper, on torn envelopes, clustered around a postage stamp of a steam engine securing magazine clippings about George Sand. Were these fragments of poems too? Lavinia recognised that she lacked the expertise to sort through the papers, but was determined that her sister’s work should be published. She turned to her sister-in-law, Sue, the woman to whom Emily had sent hundreds of poems (so many that Sue called the route between the Homestead and the Evergreens the ‘Pony Express’).

Lavinia had a difficult relationship with Austin’s wife. A neighbour recalled that ‘Sue was relentlessly cruel … I was called to Miss Vinnie’s many times to quiet her nerves and help her recover from Sue’s verbal blows.’ Is this an exaggeration? Is it true that Sue once set her dogs on Lavinia’s cats? When Sue didn’t move quickly to arrange Dickinson’s work for publication, Lavinia grew restless. She approached Higginson, who declared himself ‘extremely busy’: although he ‘admired the singular talent of Emily Dickinson, he hardly thought enough could be found to make an even semi-conventional volume’. Finally, she appealed to Mabel. (Todd later reimagined this sequence of events, accusing Sue of ‘unconquerable laziness’ and claiming that she had sat on Dickinson’s poems ‘for nearly two years’. In fact, the task fell to her less than nine months after Dickinson’s death.)

Todd immediately recognised the size of the task and urged Lavinia to be patient:

I told her that no one would attempt to read the poems in Emily’s own peculiar handwriting, much less judge them; that they would all have to be copied, and then be passed upon like any other production, from the commercial standpoint of the publishing business, and that certainly not less than a year must elapse before they could possibly be brought out. Her despair was pathetic. ‘But they are Emily’s poems,’ she urged piteously, as if that explained everything.

Todd was frustrated by Lavinia’s ignorance: she had no idea how many poems there were, or any sense of the difficulty involved in deciphering Dickinson’s handwriting. Many of the poems were ‘written on both sides of the paper, interlined, altered and the number of suggested changes was baffling’. There were ‘tiny crosses written beside a word which might be changed … and which referred to scores of possible words at the bottom of the page’. The crosses ‘were all exactly alike, so that only the most sympathetic and at-one-with-the-author could determine where each word belonged’. Todd endeavoured to remain true to Dickinson’s manuscripts in her original transcription: the editing could come later. She copied the poems by hand, then typed them up on a borrowed Hammond typewriter. This machine, as Ralph Franklin explained in The Editing of Emily Dickinson (1967), was ‘one of the earliest to have small letters as well as capitals’ and allowed Todd to remain faithful to Dickinson’s idiosyncratic capitalisation. When she was forced to return the Hammond she purchased her own typewriter, for $15. This was ‘a more primitive machine than the Hammond’ and ‘had only capitals’, making it incapable of a ‘literal rendering’ of Dickinson’s work.

Todd worked on the poems consistently between 1887 and 1889. (Lavinia made several late-night visits to admonish her for her slow progress.) In March 1889, Todd hired an assistant, but Harriet Graves proved an even more ‘insensitive machine’ than the new typewriter. She was dismissed; instead, David and their seven-year-old daughter were drafted in to help. Millicent later wrote that ‘initiation into the vagaries of Emily’s handwriting is one of the earliest rites I can recall.’

The late 1880s were difficult years for ‘the other woman’. Sue remained entrenched at the Evergreens. It stuck in Mabel’s craw that Amherst condemned her as an adulteress but turned a blind eye to Austin’s part in the affair. In 1887, she accompanied David on a trip to Japan and wrote to Austin proposing a suicide pact. If he was unwilling to do anything to relieve the ‘bigoted spite’ to which she, as his mistress, was subjected, there seemed no alternative but ‘to go together to some possibly kinder sphere’.

Austin did not reply. Instead, he presented Mabel with a wedding ring on her return. She was his true wife. ‘We stand, firm as the everlasting rocks,’ he assured her. In November 1887, he made his will; it was ‘not quite as I wanted it’, he told Mabel, ‘but best for now’. He left his share of the Homestead and the Dickinson meadow, as well as all his stocks and bonds, to Lavinia. The rest of his property he left to Sue. He assured Mabel that he’d instructed Lavinia to turn over his eight acres of the meadow to her. ‘She has promised to do this,’ he wrote, ‘so you are protected.’ In other words, he asked his sister to take responsibility for what he was too cowardly to put in writing. Early in 1888, Austin and Mabel attempted to conceive a child – something they referred to as ‘The Experiment’. Did Mabel think a baby would finally convince him to leave Sue? As the months passed, and her periods continued, Mabel grew depressed. ‘I am sorry too,’ Austin wrote to her on 28 March, ‘frightened though I was, to some extent.’ His sigh of relief rises off the page.

In the autumn of 1889, Todd arranged a meeting with Higginson, who remained unconvinced that an edition of Dickinson’s poems was a good idea. Undeterred, she tried to woo him with a reading of some of her favourites. Higginson agreed that if she sorted the poems into three categories, he would look more carefully at them. ‘Category A’ was to include ‘not only those of most original thought, but expressed in the best form’; ‘Category B’ was to include poems ‘with striking ideas, but with too many of [Dickinson’s] peculiarities of construction to be used unaltered for the public’; ‘Category C’ should comprise poems Todd ‘considered too obscure or too irregular in form for public use, however brilliant and suggestive’.

By November, Higginson’s ‘confidence’ was ‘greatly increased’. The pair agreed to prepare a volume of two hundred poems and began their ‘editorial surgery’. This involved altering words to make Dickinson’s lines conform to a conventional a-b-c-b rhyme scheme and amending her peculiar grammar. Her strange use of the third person singular had to go. ‘When Winter shake the door’ became ‘When Winter shakes the door’ in the interest of grammatical agreement. Dickinson’s subjunctives were also weeded out: ‘An Emperor be kneeling’ became ‘is kneeling’ – and so on.

Then there was her odd use of articles, as in the final line of the following stanza:

And then to dwell in Sovereign Barns,

And dream the Days away,

The Grass so little has to do,

I wish I were a Hay –

Higginson was adamant that ‘a’ should be changed to ‘the’. Todd disagreed. ‘The quaintness of the article really appealed to me,’ she wrote. ‘It cannot go in so,’ Higginson exclaimed. ‘Everybody would say that hay is a collective noun requiring the definite article. Nobody can call it a hay!’ Here, as in the majority of cases, she deferred to Higginson.

Both editors agreed that Dickinson’s punctuation should reflect ‘typographical convention’. Her underscores, quotation marks, unorthodox use of capitalisation and, most significantly, her dashes were abolished. In the 1890 edition, the final line of ‘The Grass so little has to do’ reads: ‘I wish I were the hay!’ Not only was the article changed, but so was Dickinson’s dash: the exclamation mark confers a finality, even a levity, that seems at odds with the effect intended by the original punctuation. The decision to title the poems was the greatest source of disagreement. Todd was against it: ‘I do not believe, myself, in naming them,’ she wrote in 1890, ‘and although I admire Mr Higginson very much, I do not think many of his titles good.’ She wasn’t wrong. ‘A World Well Lost’ for a poem that begins: ‘I lost a world the other day’? But, again, she conceded.

No modern reader of Dickinson will be satisfied with the Todd-Higginson edition, but the scorn directed at their editorial practices has often been disproportionate. Was there any editor in the 1880s who could somehow have persuaded a publishing house to print unedited transcriptions of Dickinson’s manuscripts? Would Sue have done a better job? Perhaps she would have opted for a small, privately funded print run that would have retained all Dickinson’s eccentricities. But Lavinia would never have allowed it. She was determined that Emily’s poems should be circulated as widely as possible. And, anyhow, in 1890, when Sue submitted one of the poems to Scribner’s in its original state (and without Lavinia’s consent: drama ensued), it appeared under the title ‘Renunciation’ and with the punctuation regularised.

Todd was right to worry that Dickinson’s ‘unconventionality might repel publishers’. Despite their attempts to render her work ‘accessible’, Houghton Mifflin, the first publisher they approached, rejected the manuscript. The poems ‘were much too queer – the rhymes were all wrong.’ David reported that ‘they thought Higginson must be losing his mind to recommend such stuff.’ Next, they approached Thomas Niles at Roberts Brothers. He told Higginson that he thought it ‘unwise to perpetuate Miss Dickinson’s poems’, which were ‘quite as remarkable for defects as for beauties’. But he agreed to send the manuscript to the critic Arlo Bates, who acted as a reader for the firm. ‘There is hardly one of these poems which does not bear marks of unusual and remarkable talent,’ Bates responded.

There is hardly one of them which is not marked by an extraordinary crudity of workmanship. The author was a person of power which came very near to that indefinable quality which we call genius. She never learned her art, and constantly one is impelled to wonder and to pity at the same time. Had she published, and been forced by ambition and perhaps by need into learning the technical part of her art, she would have stood at the head of American singers.

In spite of this, Bates recommended that Roberts Brothers publish the poems. Niles agreed to a small print run if Lavinia paid for the plates. She was initially ‘inarticulate with rage’, but Todd talked her round. She had, Todd declared, ‘as much knowledge about business as a Maltese cat’.

Mabel now concentrated on their publicity strategy. She contacted William Dean Howells, editor of the Atlantic Monthly, who agreed to write a piece on Dickinson. Of all the reviewers of the 1890 volume, Howells was the most intuitive:

Occasionally, the outside of the poem, so to speak, is left so rough, so rude, that the art seems to have faltered. But there is apparent to reflection the fact that the artist meant just this harsh exterior to remain, and that no grace of smoothness could have imparted her intention as it does … If nothing else had come out of our life but this strange poetry, we should feel that in the work of Emily Dickinson, America, or New England rather, had made a distinctive addition to the literature of the world.

Other critics were appalled that a man of Howells’s stature would endorse such work – a ‘farrago of illiterate and uneducated sentiment’, one English reviewer called it. Alice James wrote: ‘It is reassuring to hear the English pronouncement that Emily Dickinson is fifth-rate, they have such a capacity for missing quality; the robust evades them equally with the subtle.’ But by March 1891, the poems had been reprinted six times.

Even as one attempts a dispassionate account of the editing and circulation of the poems, it’s impossible not to be drawn back into the private lives of those involved: feuds, double-crossings, divided loyalties. Take this letter from Lavinia to Higginson in July 1890. Thanking him for his work, she adds: ‘I dare say you are aware our “co-worker” is to be “sub rosa”.’ Todd was justifiably outraged. It was, she said, ‘a species of treachery beyond my imagining’. But she also knew why Lavinia didn’t want her name on the book: ‘She was scared to death of Sue.’ Higginson, to his credit, demanded that Todd’s name should appear on the title page, and before his own, since she had undertaken the greater burden of the labour.

The editors immediately set to work on a second volume, which came out in November 1891 and sold ‘like Hot Cakes’. But in the course of preparing this volume – and unbeknown to Higginson, who left the grunt work to Todd – something strange happened. One fascicle (the word was Todd’s coinage) was taken apart and a poem across two pages removed and mutilated; Dickinson’s sewing holes were tampered with to conceal where it had appeared. The extracted pages were torn but not destroyed, since each sheet of paper had another poem on the reverse. Every line of the offending verse was scored out, beginning with ‘One sister have I in the house/And one a hedge away.’ The clear intention was to eliminate evidence of Emily’s bond with her sister-in-law. The final line, ‘Sue – forevermore!’, is blacked out with particular vigour. (The text survives because Sue preserved the copy Emily sent her on her 28th birthday.) Three people had access to the fascicle: Mabel, Austin and Lavinia. Franklin is adamant that Todd’s professionalism would never have allowed her to deface a poem, whatever her personal grievances: ‘The responsibility for its defacement rests with her kin.’ I’m not so sure.

Mabel certainly had a motive. But, by 1891, Lavinia’s relationship with Sue was extremely acrimonious. Sue and Mattie had refused to speak to Lavinia since they learned of the first Todd-Higginson volume in 1890. After its publication, Sue proposed a rival collection: ‘I have many manuscript letter-poems from which I mean to make up into a unique volume as I can command the time.’ Lavinia was furious. Why had Emily shared so many poems with Sue and not with her? Lavinia invoked her sister’s will, which left ‘everything’ to her, and asserted that she was the sole proprietor of anything in Emily’s hand. Sue was defeated.

Franklin concludes that it was probably Austin who mutilated the poem and cites Millicent’s Emily Dickinson’s Home (1955), which describes the way Austin censored his sister’s letters, removing any reference to Sue, when Todd prepared a two-volume edition of Dickinson’s correspondence for publication in November 1894. ‘He erased when the letters were in pencil,’ Franklin writes. ‘When they were in ink, he used heavy cancellation, substituted readings, and even cut out undesirable passages with scissors.’ This story was passed down to Millicent from Mabel, who claimed that ‘in general both Lavinia and Austin approved of whatever I did or did not do in the way of editing … They did make one request, namely, that I omit certain passages, references to a relative then living, in some of the early letters.’ Franklin takes Mabel at her word, but it’s hard to believe she wasn’t bothered by the letters Austin wrote to Emily when he was fervently pursuing Sue in the 1850s – just as it’s difficult to imagine Mabel working slavishly over a poem written in praise of Austin’s wife.

The friction between Lavinia and Mabel also intensified. Lavinia was reluctant to share any royalties from the poems with the editors. In return for their years of work, she paid them only $100 each. After the first volume appeared, Lavinia wrote to Higginson: ‘But for Mrs Todd & your self, “the poems” would die in the box where they were found.’ But she quickly changed her tune and came to consider them mere copyists. ‘In doing the work, they were only parts of the machinery, automatons, and should so consider themselves.’

It wasn’t just about the money. Lavinia became jealous of Mabel’s public talks and her reputation as the authority on Dickinson’s life and work. Austin, in an attempt to placate his mistress, got Lavinia to agree that the royalties from Dickinson’s letters should be split equally with Mabel (though Lavinia would retain the copyright as she had with the poems). He also proposed to give Mabel a strip of land ‘to make things a little more even’ and properly compensate her for editing Dickinson’s work.

In 1895, Austin’s health began to fail. He was confined to the Evergreens and, naturally enough, Mabel wasn’t granted visitation rights. ‘I really believe I have suffered more during your sickness than you have,’ Mabel wrote to him. On 18 July, Austin dragged himself to the Homestead to meet his mistress. Mabel was distraught by how feeble he had become and set off to visit a Boston faith healer in search of a cure. It was too late: Austin died on 16 August. Mabel’s diary from the following day contains just one line: ‘My God, why hast thou deserted me!’ She wasn’t welcome at the funeral, but she did see Austin one last time. Early on the day of the burial, Ned Dickinson let her into the Evergreens through a side door while the rest of the family were in the dining room. Mabel kissed Austin goodbye and hid a token of her love in the coffin.

Millicent described Austin’s death as an ‘all-engulfing disaster’ which ‘put an end, among other things, to my childhood’. Her mother now paraded around Amherst in black, an ersatz widow, declaring that she had been ‘the only bright spot’ in Austin’s life. David was devastated too: ‘I loved him more than any man I ever knew,’ he told his daughter. Two months after the funeral, Mabel went to see Lavinia about her inheritance. Unsurprisingly, Lavinia had no intention of keeping the promise she’d made in 1887 and refused to sign over her brother’s share of the family estate. Mabel was incensed. ‘She is, as he always told me, utterly slippery and treacherous, but he did not think she would fail to do as he stipulated in this.’

Athird volume of Dickinson’s poems was due to be published in 1896, and Todd had been hard at work preparing it (Higginson was by now too ill to contribute much to the project). Towards the end of 1895, Lavinia grew worried that Mabel might punish her by failing to deliver the manuscript to Roberts Brothers. She felt that she had to make some concession to the Todds – so on 7 February 1896 she signed over the land. Anxious that Sue would learn of this arrangement, Lavinia stipulated that Timothy Spaulding, the lawyer who was to witness the deed, should arrive at the Homestead after dark in case he was seen by anyone from the Evergreens.

The deed was made public when it was officially recorded on 1 April. Lavinia panicked. Longsworth writes: ‘Caught doing what she knew Sue would kill her for, [Lavinia] reacted like a child with her hand in the cookie jar. She said she hadn’t done it, which immediately got her into deeper trouble.’ By now Mabel had submitted the latest manuscript to the publishers and the Todds had set sail for Japan, where they would spend the next few months. In their absence, Sue demanded Lavinia get the land back. The Todds returned to Amherst in October, a month after the third volume was published, bringing Lavinia a present of some Japanese pottery. All seemed well. But on 16 November, they were served with papers. Lavinia maintained that her signature had been obtained fraudulently, that she had never intended to give the land to the Todds, and demanded that the deed be revoked.

The trial began on 1 March 1898. Spaulding testified on behalf of the defendants, stating he’d made clear to Lavinia what she was signing and had witnessed her signature. Lavinia, who came to court in a mourning veil, said this was untrue; she claimed that Spaulding had never spoken with her directly and that he was in another room, examining her china, when Mabel presented her with the piece of paper. She told the court she had no knowledge that she was signing a deed: ‘I understood that someone in Boston wished my autograph,’ she explained. ‘I thought that was what I was doing.’ Lavinia testified that she had never discussed signing over the land with the Todds or anyone else. Dwight Hills, a friend whom Lavinia had consulted on the matter, took to his sickbed during the trial but was forced to make a written deposition. He admitted that Lavinia had ‘repeatedly talked over with him the matter of deeding the land to the Todds’ and that he had agreed ‘to draw up the necessary papers and secure legal services’ for her.

In the end, the trial hinged on the question of reputation. Mabel was an adulteress; Lavinia was ‘the elderly surviving member of the honourable Dickinson family’. Her lawyer argued that his client ‘knew little of the world and nothing of business’. Mabel had ‘business experience’ deriving from ‘extensive travel’ and her role as a ‘public lecturer’. It would be easy for such a person to deceive poor Lavinia Dickinson.

The ruling for the plaintiff was handed down on 3 April. The Todds were ordered to return the land to Lavinia and to pay her legal costs. On 1 July 1899, Lavinia sold the strip to a developer. She died the following month. Ned Dickinson, who had supported his aunt through the trial, died three weeks after it ended. ‘Perjury always kills,’ Mabel remarked. Her diaries of the time record her sense of being ‘crushed’ by ‘the wicked injustice’ of the verdict. In 1931, however, she put a different spin on things: ‘It didn’t have the effect of a gnat’s wing on me. I went on being the Queen of Amherst and manipulated it as I wanted to.’ When the trial finished, Mabel had in her possession 655 of Dickinson’s poems – copied but still unpublished – and scores of other letters and papers. She dealt with Lavinia’s betrayal by locking them all away in a camphorwood chest, which she placed in storage. It would not be opened for a quarter of a century.

Dobrow provides a whistlestop tour of the following years. Mabel and David left the Dell – ‘I have suffered so much in the little red house!’ – and moved into Observatory House, owned by Amherst College. In 1909 (with investments from various friends) they bought a 300-acre island off the coast of Maine. Sue died in May 1913. Mabel was ‘relieved’, for Austin’s wife had been ‘cruelly perverted’, ‘done incalculable evil, and wrought endless unhappiness’. ‘At times,’ Mabel wrote, ‘she seemed possessed of a devil.’ Two months after Sue’s death, Mabel had a stroke while swimming. She was certain that the ghost of Austin’s wife had come up behind her, ‘pushed her into the pool and caused the blood vessel in her brain to burst’. The Todds decided to move to Florida, where, in their latest turn of fortune, they were given a house in Coconut Grove by Arthur Curtiss James, a multimillionaire who had financed some of David’s astronomical expeditions.

Of all those affected by ‘the war between the houses’, as the feud between the Todds and Dickinsons became known in Amherst, Millicent was the greatest casualty. ‘I began at so early an age to suffer within myself,’ she wrote. ‘I began also at an early age to be oblivious to usually accepted sources of annoyance and legitimate excuses for fear.’ Consider her description of riding in a carriage with Mabel and Austin: ‘I was sitting between Mamma and Mr Dickinson. I felt them lean together behind me. What transpired I do not know. I could have been borne rigid to a burning pyre before I would have turned my eyes.’ Austin, Millicent wrote, was ‘the somewhat terrible centre of the universe … I felt the weight of him and carried it throughout my childhood.’ She recalled a reception at the house of Amherst’s college president in the 1890s:

I saw [my mother’s] left hand bare and her right with the engagement and wedding rings which Mr Dickinson had given her … I felt sickened by such a sense of shame, such a chaotic, profound, devastating, nauseating emotion, all the more corroding because it could not be expressed, either in words or even to my own mind.

Millicent hated her mother’s ‘coquetry’, her elaborate ‘manner of dressing, so different from that of other Amherst mothers’. ‘They were hausfraus,’ she said. ‘They stayed at home and they were cooks and my mother never went near the kitchen.’ Most of all, she disapproved of Mabel’s falseness. ‘Walking along the street together in silence, someone approaches. My mother begins to talk to me in an interested manner, but without any significance in her remarks. I cannot remember the time when I did not know that it was for the sake of the effect on the passer-by.’

She envied her mother’s looks. For her, ‘everything was easy!’ She was ‘praised and admired without trying’. ‘Mamma talked and held people better than I did. She danced better than I did. The boys at a dance preferred to dance with her than with me. In a word, there just wasn’t any use in trying to compete. And I never did.’ She also felt tainted by Mabel’s reputation. ‘I was a repository,’ she wrote, ‘of the disapproval and moral condemnation of the community.’ She feared Sue and Mattie, ‘who walked about the village streets scattering venom’, and crossed the road to avoid them.

Millicent escaped Amherst and enrolled at Harvard. In 1918, she put her graduate studies on hold and travelled to France to join the war effort. She worked at a base hospital, tending to young men injured at the front: ‘their backs one great mustard gas blister, shell-shocked, eyes blown from their sockets by a too close exploding shell, or perhaps worst of all, lungs partially burned out by mustard gas’. Here, she had the misfortune to meet Sergeant Joe C. Thomas. Millicent was impressed by the thirty-year-old engineer turned physician who boasted of his PhD from the University of Chicago, where he’d captained the football team. Now 38, she lied to him about her age and fretted about the tell-tale grey in her hair. She worried when a colleague reported that Joe had ‘told his regiment that his one idea of a good time was a bottle of cognac and a French woman’, but put the obliviousness she had cultivated in childhood to good use. She and Joe got engaged after the war ended. At this point, her parents’ friend Curtiss James had Joe investigated; it turned out that he wasn’t a physician or an engineer, had not graduated from Chicago and had never captained a football team; the sister he claimed to have lost in a traffic accident was alive and well in Oklahoma; the other sister, whom Joe said graduated from Vassar, did not exist. He too had lied about his age: he was actually 22. Worst of all, it appeared that he was already married.

Millicent, who considered the kiss that sealed their engagement ‘the climax of my life’, could not accept this. When Joe stopped answering her letters, she resolved to track him down. She learned that he’d been transferred to a veterans’ hospital in Denver. By the time she crossed the Atlantic, Joe had been demobbed and sent back to his home town of Muskogee. She got on a train to Oklahoma. Joe agreed to meet her in a hotel. He apologised for the lies, but made his feelings clear: ‘I didn’t want you – I don’t want you.’ Millicent returned his engagement ring. Joe looked at it for a few moments, then flung it on the floor and left.

Heartbroken, she returned to Harvard to work on her doctorate. On 4 December 1920, she married Walter Van Dyke Bingham, a psychologist who did hold a doctorate from Chicago. She couldn’t bring herself to love Walter with anything like the ‘dazzling, frightening intensity’ she’d felt for Joe. There are fewer than a dozen photographs in her wedding album – and none of the bride and groom together. In one shot, Millicent appears alongside her stylishly dressed mother. She looks dowdy by comparison. Even as a recovering stroke victim, Mabel outshone her daughter. ‘The glow never disappeared,’ Millicent wrote. ‘It scarcely dimmed at all.’

Shortly after their marriage, Millicent learned that Walter had had several sexual relationships. To his puritanical wife, this placed him ‘down on the level with the common herd’. Over the years, however, she grew to appreciate him – especially his help with her ageing parents. David had become obsessed with establishing life on other planets: ‘Some of his efforts involved ascents in hot air balloons with equipment he invented to send and receive signals from Mars.’ He accrued large debts and remortgaged the house in Florida to fund a movie about the Everglades. He sent Millicent to fetch parcels from people who did not exist. In 1922, the Binghams had him evaluated by a psychiatrist and committed to an asylum. For the rest of his life, he was in and out of such institutions. He was suffering from paralytic dementia, a complication of late-stage syphilis. None of this bothered Mabel, who thrived in Florida, delighting in her extravagantly decorated home, which became the cultural hub of the community. In 1923, Millicent completed her PhD, but her career as a geographer was short-lived. The feud with the Dickinsons, which had lain dormant since Lavinia’s death in 1899, was about to erupt again.

The copyright on Todd’s edition of Dickinson’s letters expired in 1922. Mattie, as the only surviving member of the Dickinson family, now sought to assert her right as ‘sole heir’ to her aunt’s papers. Word spread that she planned to publish two books: The Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson and a Complete Poems. Was Mattie’s intention to rescue her aunt’s work from its association with Todd or was she simply short of cash? It was a bit of both. In 1902, she had suffered a breakdown and told a friend she had ‘a bully time killing myself’. A doctor advised her to take ‘a year’s rest abroad’. Before setting sail for Europe, however, she encountered Alexander Bianchi, a Russian captain in the Imperial Horse Guards. He pursued her across the ocean and they were married on 19 July 1903 in Marienbad. The captain, it transpired, was another Joe Thomas. Caught up in several fraudulent business deals, he drained his new wife’s fortune paying off his debts and settling various lawsuits. In 1916, she was forced to sell the Homestead to keep things afloat. The pair divorced in 1920, but Mattie kept Bianchi’s surname. Perhaps she thought it glamorous.

In 1914, she brought out The Single Hound, a collection of the poems Dickinson had sent to her mother. ‘One sister have I in the house’, the verse mutilated in the 1890s, was the ‘dedicatory poem’. The Todds did not object to The Single Hound, but the volumes that appeared in 1924 were different. These ‘new’ books appropriated Todd’s editorial work, but removed all reference to her and declared ‘Martha Dickinson Bianchi’ editor. Her Complete Poems consisted of the three volumes Todd edited in the 1890s, along with the poems in the 1914 volume. Her edition of the letters was largely a reprint of Todd’s 1894 edition: 272 of its 381 pages were identical. The passages she inserted about her aunt – this was a Life and Letters after all – were full of sloppy mistakes. She got Emily’s middle name wrong and gave incorrect dates for her birth and death. She was even confused about when her own brother had died.

To begin with, David was more perturbed by this than Mabel. In 1924, he complained angrily to Millicent from the asylum: ‘Are you going to sit by and do nothing while the work on which your mother spent years is pirated and her name erased from the title page?’ But Todd was simply biding her time. ‘With Mamma’s characteristic refusal to face facts,’ Millicent wrote, ‘she thinks she will outlive Bianchi and then do something! Not realising that she is ten years older.’ ‘What an orgy we shall have!’ Mabel exclaimed, anticipating the death of Dickinson’s niece. But Mattie, like Sue before her, kept on keeping on. She scoured the papers she had rescued from the Homestead after Lavinia’s death and found a hoard of unpublished poems. In 1929, she published Further Poems of Emily Dickinson Withheld from Publication by Her Sister Lavinia. This finally roused Todd to action. These were the poems she had copied all those years ago and planned to publish in a fourth volume before Lavinia double-crossed her.

She enlisted Millicent’s help. Together, they prised open the camphorwood chest. It contained hundreds of poems in brown envelopes; those Todd had copied for the first three published volumes, as well as those she had copied in anticipation of a fourth (most of the originals had been returned to Lavinia); but there were also manuscripts in Dickinson’s hand, among them six fascicles, numbered 80 to 85, which included a trove of unpublished poems. Millicent noted there were also many ‘rough drafts and practice pieces – “scraps” my mother called them. Some of these were perfect poems. Many, though complete, were interlined with alternative readings. Others were mere fragments.’ Then there were letters – packets upon packets, many of which Todd had excluded from her volume in 1894.

Mother and daughter set to work preparing an expanded edition of the letters. Mattie’s attempts to block the publication were unsuccessful. The new edition sold out on 5 November 1931, the day it was published. But even critics who hailed Todd’s edition as ‘accurate and definitive’ were quick to point out that without Dickinson’s letters to Sue, it was not comprehensive. Of course Mattie would have denied Mabel access to her mother’s letters, but it would be ridiculous to think that, given the choice, Mabel would have let Dickinson’s letters to Sue see the light of day. This was the woman who had returned from the dead and tried to drown her in a swimming pool.

Next, Todd set about arranging the remaining Dickinson poems in her possession. In the summer of 1932, she attempted to get her daughter to commit more fully to the project. ‘It is all wrong, Millicent, everything that has happened. Will you set it right?’ Millicent said she would ‘try’, but agonised over what this meant for her career. Then, on 14 October, Mabel died suddenly of a cerebral haemorrhage. On her gravestone is a carving of the Indian pipes picture she sent to Dickinson in 1882.

Millicent felt her duty to ‘make things right’ more keenly now. She had tried very ‘consciously’ to plough her own furrow, but was always drawn back to the Dickinsons as if by ‘irresistible compulsion’. In the end, Walter helped make up her mind:

You know, other people can do geography. They can even do French Geography; but there is nobody who has been in this other situation all their life who knew all the members of the family … and who began at the age of seven to read Emily’s handwriting … I want you to realise just one thing – there is enough power in this situation … to get us both before you finish.

‘I had no alternative but to drop geography,’ Millicent wrote, ‘and try to inject some integrity into the Dickinson controversy.’

In many ways, she was a more sensitive editor than her mother. She did her best to decipher Dickinson’s interline corrections and ‘in no single instance … substituted a word or phrase not suggested by Emily herself’. But Dobrow’s claim that, ‘for the most part, Millicent left Emily’s unique punctuation intact’ is bizarre. You would struggle to find a poem in her edition that preserves the original punctuation. But she did abandon Todd and Higginson’s practice of naming the poems, except in instances where Dickinson herself indicated a title.

She also paid careful attention to Dickinson’s fragmentary poems, which Mabel had written off as ‘hopeless’ scraps, piecing together bits of torn paper and deciphering lines written in the margins of newspapers, on brown paper bags, on envelope flaps, on discarded bills, on mildewed subscription ads and drugstore flyers, on shopping lists, on butcher paper, on the back of a recipe for coconut cake. (Dickinson was a keen baker: her rye and Indian bread won second place at Amherst’s annual cattle show.)

When Mattie died in 1943, Millicent’s edition was ready to go. Bolts of Melody, which included more than six hundred unpublished poems, appeared in the spring of 1945. The same year, she brought out Ancestors’ Brocades, a book that attempts to vindicate her mother’s editorial procedures. Millicent hoped her work would settle things for good, that the feuds which had plagued the dissemination of Dickinson’s work were now ‘dissolved in death’. More fool her. Another row was about to kick off, this time over Dickinson’s archive and where her papers should reside.

By the mid-1940s, Dickinson’s manuscripts had become hot property. With no biological heir, Mattie had willed everything to Alfred Leete Hampson, her companion of many years. The bequest included two-thirds of Dickinson’s papers. The remaining third were in Millicent’s possession. Harvard was particularly keen to procure the archive. Millicent was approached by William A. Jackson, the head librarian at the Houghton, nicknamed Harvard’s ‘Grand Acquisitor’. She told him – and the Library of Congress, which also declared interest – that she would make no decision about the papers until she had completed two final books on Dickinson. Meanwhile, William McCarthy, head of cataloguing at the Houghton, worked on winning over Hampson, visiting him in Amherst and arranging for a childhood portrait of Emily, Austin and Lavinia to be restored at the university’s expense. (He applauded the lush auburn of Emily’s hair after its ‘shampoo’.) Hampson’s chronic alcoholism had resulted in cirrhosis. When Mary Landis – whom Hampson married after Mattie’s death – was out of town, McCarthy stepped in to look after him. Armed with a torch, McCarthy used his time at the Evergreens to rummage for papers that Mattie might have overlooked when preparing her editions of Dickinson’s work. He preyed on Hampson’s fears that the precious papers would be damaged in the crumbling wreck of the Evergreens. What if there was a fire? What about damp? What if the ceiling caved in? Hampson, who carried portions of ‘Emily’ in his suitcase whenever he travelled, was terrified.

In 1948, McCarthy left Harvard to work for the Rosenbach Company, a rare book and manuscript dealer in New York. He told Hampson that he had made the move in order to ‘care for Emily’ and ensure her papers ended up in the right place. With medical bills piling up, Hampson needed to get his hands on some cash; his plan to keep hold of the papers until he had written a biography of Mattie was abandoned. In January 1949, McCarthy got the go-ahead to act as the exclusive dealer for the Dickinson papers. Rosenbach was to receive 10 per cent of the sale price and paid Hampson an advance of $5000 to tide him over. Dickinson’s poems would be stored in the company vault, while the manuscripts of her letters were kept safe in McCarthy’s New York apartment.

If McCarthy was to establish a ‘shrine’ to Dickinson at some illustrious university library, he would need a benefactor in whose name a bequest could be made. Luckily, William Jackson, his old colleague at Harvard, had joined forces with a distant relative of the Dickinsons, Gilbert Holland Montague, from whom Mattie had sought legal advice during her divorce. Montague, a very rich and very nasty man, briefly taught economics at Harvard (where Roosevelt was among his pupils) and went on to become a big New York lawyer. In an effort to cast himself as a philanthropist, he decided to spend some spare change acquiring the papers of ‘My cousin, Emily Dickinson’.

Jackson appealed to Montague’s business instincts, telling him that Millicent had promised to give her share of the papers to Harvard for free – though she had done no such thing – which would increase the donation made in his name by a third. In February 1950, when McCarthy called Hampson explaining that Harvard wished to purchase Dickinson’s papers for $50,000, he failed to mention that Montague was the university’s financial backer. (Hampson had been less than forthcoming when Montague approached him directly.) In March, Montague set out his terms. He would pay Hampson $25,000 upfront; the remainder would be paid in annual instalments of $5000 from 1951 to 1955.

At this point Hampson got cold feet, suspecting Emily’s papers might fetch more if he sold them off in batches. If he took the deal, he would be left with only $15,000 in the spring of 1950, once his $5000 advance had been deducted and he had paid Rosenbach 10 per cent. Montague waged ‘a war of nerves’ on Hampson. Lawyers’ letters descended on the Evergreens: if Hampson backed out of the deal, he would be dragged through the courts. Montague had no legal basis for this intimidation – nothing had been signed – but he exploited Hampson’s naivety. Meanwhile, Rosenbach threatened to send the manuscripts to Harvard with or without Hampson’s consent. In late April, Hampson suffered a haemorrhage and was rushed to hospital. By the time he signed Rosenbach’s deal on 6 May, he had received seven blood transfusions and was in no shape for a fight. William Jackson wrote to Montague celebrating ‘V-Emily Day’.

When the official press release went out on 31 May, Montague received a hundred letters of congratulation, including one from General Eisenhower. His secretary answered each and every one. Millicent was surprised by the acquisition, but sent her best to Montague and wrote of her ‘relief’ that Hampson’s portion of the papers was secure. Montague was thrilled with her letter, and circulated copies, but he would prove as ruthless with Millicent as he had been with Hampson.