When Jacques Carbonnel went to Algeria to do his army service in 1956, his wife, Jeanne, asked him not to hide anything from her. ‘You want me to tell you everything,’ he wrote to her soon after arriving. ‘It’s ugly and you are too pretty. We arrest suspects, we release some, we kill some – it’s the dead runaways you see in the newspapers, phoney runaways! We push some out of helicopters above their villages. Criminal, inexcusable. The military solution doesn’t work here.’ Three days later, after returning from a two-day operation, he explained the method the army used to make suspected rebels talk: ‘We fill them up with water. We put a pipe in their mouths, in the anus, and we open the tap.’

Carbonnel was one of 1.5 million conscripts – appelés – who were sent to Algeria to defeat a nationalist uprising: an entire generation of young men in their early twenties. (The population of France in 1954 was 43.3 million.) But they were not at war, at least not officially. Algeria had been conquered in 1830 and administered as an integral part of France since 1848, when it was divided into three départements. More than a million European settlers lived there as French citizens. In Algeria the French were chez eux: according to a popular saying, the Mediterranean separated France from Algeria just as the Seine in Paris divided the Left Bank from the Right. When the rebels of the Front de Libération Nationale launched their war of independence in November 1954, France referred to them as hors-la-loi, outlaws rather than combatants. By the time Algeria won its independence in July 1962, hundreds of thousands of Algerians, and roughly 24,000 French soldiers, were dead. Algeria was liberated after more than a century of colonial domination, and France woke up to find itself stripped of its most prized imperial possession.

Yet France still refused to call les événements a war. Instead, this was ‘an operation to maintain order’. The French state did not formally recognise that it had fought a war in Algeria until 1999. It was another two decades before it admitted to the systematic use of torture. In 2018, Emmanuel Macron acknowledged France’s responsibility in the murder of the pro-independence militant Maurice Audin, a communist mathematician who was ‘disappeared’ in 1957 – but passed over in silence in the extrajudicial murders of FLN leaders such as Ali Boumendjel and Larbi Ben M’hidi, who were ‘suicided’ in French custody during the Battle of Algiers. Even today, access to the war archives means overcoming significant bureaucratic obstacles. Denial, secrecy and subterfuge around Algeria coincided with the increasing commemoration of the deportations of Jews under Vichy, as if remembering the Holocaust and forgetting Algeria went hand in hand.

If the wall of denial has crumbled, it is in no small part thanks to the work of historians such as Raphaëlle Branche, who in 2001 published a doctoral thesis, La Torture et l’armée pendant la guerre d’Algérie, based partly on interviews with former appelés. Branche belongs to a generation of French historians who have exposed the cruelties of France’s counter-insurgency against Algerian nationalism; many of these scholars are women, most of them born at least a decade after the end of the war. Their work has substantiated and expanded on the contemporary accounts of torture and assassinations by leading anti-war militants, in particular Pierre Vidal-Naquet and Henri Alleg.

The title of Branche’s new book – Papa, qu’as-tu fait en Algérie? – suggests a continuation of this muckraking, but the subtitle points to a shift in focus: ‘An Inquiry into a Family Silence’. Branche’s aim is not so much to refute state denials as to show the way that denial was lived by the appelés and their families during and after the war. Her research is in large part drawn from conversations with 39 families; some she knew from her first book, while others she met through associations of anciens combattants. She spoke with ageing veterans about their experiences, asked them to fill out extensive questionnaires, and read letters they had sent to their wives, girlfriends, parents and siblings, as well as their (far more explicit) journals. But she also wanted to know how the war was discussed at home, especially after France’s defeat, when appelés were scrambling to reintegrate into society and raising families of their own. Or, rather, how it wasn’t discussed. One soldier’s son said Algeria was always in the air, but as a ‘non-event that can only be guessed at in the negative, by the absence of words that surrounds it’. Branche took on this absence of words not simply as a challenge for her research, but as its subject, an expression of the ‘structures of silence’ that shaped the lives of millions of French people affected by the war. (In Le Trauma colonial, published in 2018, the Algerian psychoanalyst Karima Lazali compares the impact of colonisation and war on successive generations of Algerians to ‘the marks of bodily amputation’.)

Silence follows war and the appelés were accustomed to it well before they set foot in Algeria. Born between the mid-1930s and the early 1940s, they grew up in the shadow of economic crisis, two world wars and the German occupation. Many had fathers and grandfathers who had fought in the trenches or in the Resistance. Although the French government had banned corporal punishment in the home in 1928, most families ignored this. The vast majority of appelés had left school young, often to work under their fathers. More than 90 per cent of French children were baptised, and about a quarter were practising Catholics. In a survey conducted for L’Express in 1957, the sociologist Henri Lefebvre found that 76 per cent of young people expected to live in the same world as their parents, ‘and in continuity with them’.

The appelés scarcely needed to be pressured into military service. Besides – as more than one appelé was told – ‘going to Algeria is no more dangerous than driving from Paris to Nice.’ (At that time about ten thousand people died every year on the autoroute.) War meant the Battle of Verdun, where more than 160,000 Frenchmen died, and Algeria wasn’t Verdun. The right of conscientious objection wasn’t recognised. Even the Communist Party condemned those who refused to go to Algeria: in 1956 it voted in favour of giving the government ‘special powers’ to crush the insurrection, and it instructed conscripted party members to promote communist ideas within the army, and to convert other soldiers to the cause of peace.

The appelés arrived in Algeria by boat, from the port of Marseille. Algeria may have been ‘France’, but for most conscripts it was their first time overseas. Enchanted by the landscape, the blue-green sky and the dramatic bay of Algiers, they sent home postcards of 19th-century paintings. ‘The topics of Orientalism are there,’ Branche writes, ‘in a folkloric eternity from which war and modernity are excluded.’ As they travelled into the countryside, where the FLN maquis was based, they were struck by how French it looked: as one soldier put it, ‘aside from the storks one sees everywhere, and the Muslims, you might think you’re on a farm in Normandy.’ Others were shocked by the misery of the indigenous population and the lack of electricity in the homes they raided. France’s vaunted ‘civilising mission’ was, in the words of one appelé, ‘only a façade, a movie set’.

The Algerians they encountered constructed a façade of their own to protect themselves from the encroachments of the army, and few soldiers penetrated it. One of Branche’s appelés fell in love with an Algerian woman, the widow of an FLN militant with whom she’d had a child. His friends in the army told him he was crazy, and suspected that he was being set up; he asked her to marry him, but by the time she wrote back, he had returned home. This level of intimacy was unusual. It’s true that conscripts often fought alongside Algerian militiamen, auxiliary forces known as harkis who were slaughtered en masse by the FLN after the war. But their encounters with ordinary Algerians tended to be instrumental and pragmatic, disfigured by suspicion and fear, when they weren’t physically brutal. Most soldiers’ experience of Algerian life amounted to the occasional méchoui feast in villages they occupied, and the photographs they took of the ‘natives’. Other mementos were seized during searches. Soldiers told themselves they weren’t stealing, just ‘bringing back souvenirs’ from the fellagha, the rebels. One former appelé told Branche about his most treasured souvenir, a helmet with the FLN insignia sewn into it. These objects, she notes, were seldom displayed in the appelés’ homes: they were hidden in drawers, along with photographs of Algeria, part of a ‘secret life’ to which family members had little or no access.

Correspondence was subject to military censorship, but self-censorship was even more effective in concealing the realities of war. The appelés were keen to reassure their parents of their safety, or to flirt with their girlfriends. Writing letters was a means of escape. Michel Berthelémy wrote to his family every two weeks, but never mentioned the day his ‘world crumbled’, when he fired a shot in fear from a balcony only to realise he’d killed a teenage boy. Jacques Senesse, a 27-year-old doctor, avoided telling his wife that a settler had been égorgé – slit across the throat – on the street he walked down every day. He had another reason for discretion: he was still fuming at her remark that she’d find him ‘contemptible’ if he didn’t serve. Still, he made sarcastic reference to his anxieties by saying that he might as well ‘get my balls cut off by a Berber … so that you can rejoice in the general esteem of being a widow and I can be decorated with a posthumous Légion d’honneur’. The sight of dead soldiers, their throats slit open (the so-called ‘Kabyle smile’), created a terror of falling into rebel hands. ‘You can’t escape it,’ one soldier wrote. ‘Corpses awfully mutilated, incredible … It’s not even a war, it’s a nightmare.’

In their letters and journals, some appelés, often from backgrounds on the left, documented the army’s contribution to the nightmare. Marcel Yanelli, a young communist, wrote in his diary about his attempts to teach his fellow soldiers to respect the laws of war. After a month in Algeria, he had already fallen into ‘shame and despair several times … How many more tortured men, pillages and deaths will I see?’ In a letter to his father, Michel Louvet described the systematic burning of forests, and explained the term corvée de bois, or ‘firewood duty’, in which suspects were told they were free to go, and then shot in the back for trying to escape. He also explained le téléphone, a current of 220 volts, with one pole on the genitals, the other inside the cheek. These practices, he said, were what ‘pacification’ really meant. (Louvet was lucky he could confide in someone trustworthy. In one of the book’s most troubling stories, Branche writes of a young paratrooper who suffered a nervous collapse after witnessing the torture of a group of children. He told his priest, who told the archbishop of Paris, who buried the news.)

What horrified appelés like Yanelli and Jacques Inrep, a socialist militant, was not simply what their fellow soldiers were doing to Algeria, but what Algeria was doing to them. ‘They are no longer men,’ Inrep wrote to his brother. ‘They’re beasts who think only of killing and raping.’ Soldiers often made comparisons with Nazism, especially with the massacre of Oradour-sur-Glane, a village in the Limousin where the Germans had responded to the capture of one of their officers by killing almost all its inhabitants. ‘How many Oradours in Algeria?’ one soldier asked. ‘For details, refer to the Gestapo in France … The methods are the same, except that … the police here use the means at hand: dynamo current, feet, fists, salt.’ Paul de Bessounet, who grew up in a part of the Haute-Loire where the Resistance had suffered heavy losses, told Branche that he felt as if ‘we were the invaders like the German army in France in 1940, the SS. So the rebels, the fells, were the maquisards.’

In Laurent Mauvignier’s novel about the war, Des hommes (2009), published in English as The Wound and recently made into a film by the Belgian director Lucas Belvaux, a young appelé ‘thinks of what he’s been told about Oradour-sur-Glane’ while wandering through an empty village razed by the army. This was a typical scene, repeated methodically throughout the countryside during the war, when more than two million villagers – nearly half the rural population – were forcibly evicted from their homes and moved into ‘resettlement’ camps (camps de regroupement). Their villages were declared ‘forbidden zones’ where anyone who remained could be killed as a rebel; their governing councils, known as djema’a, were dismantled. Soldiers set fire to forests, raped women, and destroyed harvests and livestock. It is no surprise that some of the most appalling testimonies collected by Branche record the army’s destruction of rural Algeria, until recently one of the most overlooked aspects of the war. As Pierre Bourdieu and Abdelmalek Sayad argued in their book Le Déracinement (1964), the policy of resettlement led to one of the harshest population displacements in modern history. The official aim was to protect villagers from the FLN, but the real purpose was to ‘disintegrate the native social order in order to subordinate it’, and to destroy the rebels, who continued to provide clandestine assistance to the peasants behind barbed wire in the camps. (The existence of the camps was first revealed in 1959 in a scathing report, soon leaked to the press, by Michel Rocard, then a 28-year-old inspector of finances in French Algeria.)*

Resettlement was a repetition of the war of ‘pacification’ France had conducted when it first conquered Algeria. ‘It is essential to resettle a people that live everywhere yet nowhere,’ Captain Charles Richard had written in 1846. ‘The essential thing is to make them accessible to us. When we have done that, we will then be able to do many things that seem impossible today, and that will permit us to win their minds after we have won their bodies.’ More than a century later, resettlement allowed for Algeria’s ‘modernisation’ by ‘depeasanting’ the rural population and bringing about the end of traditional agriculture. The rural geography of contemporary Algeria still reflects the geography of resettlement.

Herding Algerian peasants into camps and destroying their villages in order to deprive the rebels of a sanctuary was part of the ‘civilising mission’, and soldiers learned that it wasn’t finished when they returned home. As one government brochure put it: ‘Soldier yesterday, civilian today, you’ve been enriched by an experience and an enthusiasm that you must communicate to those around you … and you, WHO KNOW, you will tell them THE TRUTH.’ Some did their duty as propagandists; the Union nationale des combattants would later emerge as a ferocious champion of Algérie française, defending the war as a conflict between Western civilisation and Islamic fanaticism. But for others, telling the truth about the war meant going into active resistance against it. When Yanelli came back, he gave his handwritten journals to friends in the Communist Party, who had them copied and circulated. Inrep created a clandestine network to fight against the Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS), a right-wing terrorist group that killed as many as two thousand civilians in Algeria and carried out assassinations in France. His father, a former résistant, reactivated his old network and collected arms for Inrep.

When France pulled out of Algeria in 1962, the remaining appelés came home to a country that was no longer the one they’d left. The Nouvelle Vague was at its height and most people had already moved on from ‘the events’ on the other side of the Mediterranean. Many of the returnees shared the desire to put Algeria behind them, some to the point of deliberately ‘disaffiliating’ from other soldiers. But it wasn’t easy to forget what they’d seen and what they’d left behind. One man described himself as a ‘prisoner’ of his Algerian memories; the most common reaction for Algeria’s prisoners was to flee into oblivion. One day the screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière and his wife went to the Seine and threw in all the letters they’d written to each other during the war, two letters a week, for two years.

Forgetting wasn’t just a personal decision: it was state policy. As Branche writes, the ceasefire between the French government and Algeria’s provisional government included a decree of amnesty for ‘things committed during operations to maintain order directed against the Algerian insurrection’. This decree not only gave immunity to those who had committed (and ordered) war crimes; it studiously avoided the word ‘war’. It took another twelve years and a long battle by appelés’ associations for soldiers in Algeria to be recognised as combattants and so become entitled to the rewards of service. Because Algeria hadn’t been a war, demobilisation was ‘dislocated from any collective experience’, without the processions or parades that traditionally followed wars. The absence of pomp and circumstance was not universally resented. The FLN and the OAS both had agents in the metropole after the war, and some veterans thought it wise to keep a low profile, fearing reprisals on French territory.

Denial strongly shaped the way the returnees were perceived by others. Bernard Porrini was told by a neighbour that nothing in Algeria could compare with what her husband had experienced as a Nazi prisoner. Family members had often been misled by the innocuous letters they’d received from the appelés during the war and assumed little had happened. Many didn’t want to have that impression dispelled. Michel Berthelémy tried to tell his family about the boy he’d killed, but ‘saw no curiosity on their part’. Many found it impossible even to attempt to talk about what they’d seen. In the 1960s, the stereotype of the Algerian returnee was of an aggressive, vaguely psychotic lout, a know-nothing redneck – depicted as le beauf in cartoons by the Charlie Hebdo illustrator Cabu. That le beauf’s personality might have its roots in what Frantz Fanon called the ‘mental disorders’ of the war was almost entirely lost on the French medical establishment at the time. Until 1969, students working in the field of military medicine used a manual published in 1935. Doctors dismissed accounts of war-induced mental disturbance by claiming that a damaged patient was ‘talkative, boastful and happy with himself and his uncontrollable stories’. This attitude persisted even as French writers and filmmakers examined the war’s legacies. In Daniel Anselme’s novel La Permission (1957), a soldier, now back in France, is having dinner with a fellow appelé when he’s seized by the feeling that ‘they’d died long before, with a bullet to the head in some far-off wadi, and that before they could touch the food, the others were going to notice, get up, and shout.’ The young returnee in Alain Resnais’s Muriel ou le temps d’un retour (1963) is a volatile man-child, haunted by the memory of a girl he tortured in Algeria. The butcher played by Jean Yanne in Claude Chabrol’s Le Boucher (1970) has returned from Algeria only to become a serial killer, condemned to continue taking lives. ‘I see blood everywhere,’ he says. The ‘war without a name’ was imagined as a forever war of the mind, an enduring mental affliction.

Jacques Inrep was among the first psychologists in France to recognise the long-term effects of the war on combatants. While working as a psychiatric nurse in the late 1960s, he realised that many of his patients were appelés, though he didn’t initially ‘make the link with the war’. Many were violent, often towards their wives. One patient remembered his use of the gégène (electric shock torture) in the Aurès Mountains, and of pornographic images to intimidate women. This provoked Inrep’s own memories: he, too, had served in the Aurès, where he had witnessed rape and torture. After his patient committed suicide, Inrep went into clinical psychology, keen to understand the ‘mental destructuration’ that occurs in ‘limit situations’. In the 1980s, he found a professional ally in a left-wing psychiatrist, Bernard Sigg, who had deserted in 1960 after treating veterans in a military hospital in Casablanca. Sigg had become persuaded that they suffered acutely from shame at having fought ‘under the sign of transgression’, that is, by carrying out crimes against the laws of the Republic in whose name the war had allegedly been fought. It is thanks to researchers such as Inrep and Sigg that the war’s psychological toll has been widely, if belatedly, acknowledged, including by the French state. Since 1992, three decades after the ceasefire, soldiers suffering from psychological issues related to the war have been entitled to compensation. American psychiatry recognised post-traumatic stress disorder in 1980, five years after the fall of Saigon.

How many of the returnees suffered from PTSD? In 2000, Le Monde estimated as many as 350,000 veterans. Branche has no medical background, and is careful not to make extravagant claims about the nature or extent of the suffering. But she is a sensitive guide to the torments experienced – and inflicted – by French soldiers, from despair, agitation and alcoholism to mental illness, suicide and violence. The daughter of one appelé, Isabelle Roche, walked into the bathroom one day to find her father waterboarding her younger brother. After being taken into care, Roche’s brother fell into petty crime, and later murdered his girlfriend and killed himself. While driving to his son’s funeral, Michel Roche remarked that it was ‘hot like it was in Algeria’, even though it was freezing outside. After her father’s death, Isabelle found a box of photographs from Algeria in his apartment and a scrap of paper on which he had written: ‘I want to live.’

The psychological effects of war exacerbated the political pathologies of colonisation, especially what Branche calls the ‘special racism’ directed at people of Algerian origin in France. During the 1970s and 1980s, the far right drew much of its energy from veterans of the war – the former paratrooper and torturer Jean-Marie Le Pen among them. They felt betrayed by the politicians who had ended the war only to permit hundreds of thousands of Algerians and other Muslim immigrants to settle in France. (Mauvignier’s novel Des hommes revolves around a crazed beauf who breaks into the home of an Algerian family in a French town, lashing out at ‘dirty Arabs’ as if the war hasn’t ended.) But Branche is less interested in what soldiers said in the public square than in what they didn’t say at home. Their silences about the war, she insists, were ‘shared silences’. Millions of French people participated in maintaining them: the veterans who wanted protection from their memories, and the family members who wanted to protect them and often preferred to be left in the dark.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the structures of silence began to collapse. The retired general Paul Aussaresses brazenly recounted his role in murdering FLN leaders during the Battle of Algiers and framing their deaths to look like suicides. Louisette Ighilariz, a former FLN militant, gave a harrowing interview to Le Monde about her torture and rape, and her search for the French doctor who had rescued her from her interrogators. These testimonies, along with the publication of new books by Branche and other young historians, prompted many long silent veterans to share their stories of the war. It was, as the son of one veteran joked, a kind of ‘coming out’. But it was also an attempt to understand their experiences. Renaud Beaufils, who refused to speak to Branche when she was writing her first book, contacted her because he wanted to know more about a clash in which a dozen of his fellow soldiers were killed. ‘I no longer know if I lived that period,’ he told her. Berthelémy admitted to Branche that after his failed attempts to speak about his killing of the young boy, he all but suppressed his own memory of it. Later he was reminded of it in a dream in which he was judged and condemned for the crime. Berthelémy, a long-time activist in an anti-war veterans’ group, urged his fellow soldiers to speak to Branche, and many of them did.

But Branche doesn’t end with the soldiers. She understands that the story of the war – a ‘history of transmission’, as she calls it – continued with their children, ‘repositories of a suffering that didn’t belong to them directly, but whose persistence they revealed’. Even in homes where mention of Algeria was taboo, its traces were disclosed in ‘little touches’: old snapshots, confiscated ‘souvenirs’, the use of Arab words like clebs for dog, kawa for coffee, bled for village. Olivier Feiertag’s first name referred to the olive trees his father had seen in Kabylia. When he was twenty, Feiertag discovered an illustrated manual of killing methods in his father’s attic – and with it, as Branche puts it, ‘an unknown father’. Only when his father was dying did Feiertag learn that his middle name, Bernard, belonged to his father’s best friend – a soldier killed as a result of a ‘regrettable error’, never spelled out. As the child of another veteran said: ‘War is an inheritance.’

Children weren’t simply witnesses to their fathers’ suffering. They helped sustain the ‘structures of silence’ they had inherited, and assumed some of that suffering as their own. In February 2019, Branche received a letter from the daughter of an appelé who had died more than twenty years earlier:

This morning, at five o’clock, I finally began your book on torture and the army in Algeria. I have formulated this phrase for the first time: so my father was a war criminal. It was an immense vertigo, an infinite pain. To write it, and, even more so, to think it, was truly unbearable. I know the devastation this war caused for him and for us, his family. The gégène and the corvée de bois were my childhood ‘companions’. Words, gestures, noises … photographs (since then deliberately hidden by my mother), anchored in our family history. It kept needling away at us, endlessly, without being explained, like any good family secret.

Today the war is no longer a secret in France, much less a family secret. For one thing, it doesn’t belong to a single national family, even within French borders. There are simply too many people of Algerian origin in France for the war to be told as a narrowly French story (much less suppressed), and they have their own complicated family memories. While many are from families that supported the FLN, France is also home to people whose families backed the Algerian National Movement (violently crushed by the FLN during the war), or who fought for France and were lucky enough to make it to the metropole after the war. Like the appelés described by Branche, they erected their own structures of silence. These have been slower to crumble, because to speak candidly about the Algerian experience of the war is to speak about the killing of Algerians by other Algerians, and thereby to undermine the FLN myth of a nation united in resistance – a narrative that almost exactly echoes the Gaullist myth of France’s unity against the German occupation.

Last year, Macron, the first president of France to be born after the war, launched a project with the Algerian government to ‘reconcile’ French and Algerian memories of the period. To lead the French effort, he recruited Benjamin Stora, a distinguished historian of the war who grew up in a Berber-Jewish family in Constantine before settling in France. The symbolism of Macron’s initiative seemed inspiring. But in his announcement, as Branche noted in a recent interview, Macron – who had denounced colonisation as a ‘crime against humanity’ while running for president – avoided the word ‘colonial’. His idea of reconciliation is modelled on the two world wars, as if the French-Algerian war were an episode that could be neatly bracketed. But the war grew out of a history of colonisation that began in 1830. And the boundaries of the French project in Algeria were never limited to Algeria itself: colonisation led to the emergence of a vast Algerian diaspora and to an intricate web of relations that continues to bind their descendants to France. The war ended, but the story of France and Algeria did not; it has shifted to the metropole, where the question of co-existence – and equality – is far more urgent than the reconciliation of wartime memories. Stora is well aware of this, and his vision of French-Algerian reconciliation is admirably expansive. His report, submitted to the Elysée on 20 January (it will be published next month as France-Algérie, les passions douloureuses), puts forward some thirty recommendations to the French government, including the formation of a ‘memories and truth commission’ to study the country’s history in Algeria. (It omits a call for ‘repentance’, in Stora’s words a ‘trap of the far right’.)

Macron has promised to establish the commission, but even if it succeeds, he will have done nothing to alleviate the alienation of French citizens of Algerian descent, who feel that they’re all too often treated as a foreign presence and a threat to French ‘values’, above all laïcité. Even the most secular members of this community fail to see why the defence of laïcité and free speech requires that schoolchildren be exposed to derogatory caricatures of the Prophet – or why objecting to them should be construed as support for terrorism. For some, Macron’s singling out of Muslim ‘separatism’ as a danger to France stirs memories of the French army in Algeria, where it fought to ‘liberate’ Muslims from religious conservatism, notably by forcibly unveiling women in the street. Anxious not to be outflanked on the right by Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National, Macron has shown little desire to make conciliatory overtures to French Muslims. And since the beheading of the schoolteacher Samuel Paty by a young man of Chechen origin, he has dug in his heels, attacking anyone who dares to criticise the increasingly repressive application of laïcité as a terrorist sympathiser or ‘Islamo-gauchiste’. In a recent interview with Mediapart, Stora was asked how Macron could preside over the reconciliation process while fulminating against Muslim ‘separatism’; he carefully finessed the question. But Macron’s Algerian war initiative is losing out as he struggles to appeal to an electorate whose sympathies lie elsewhere. The latest poll puts Le Pen almost level with Macron in next year’s elections.

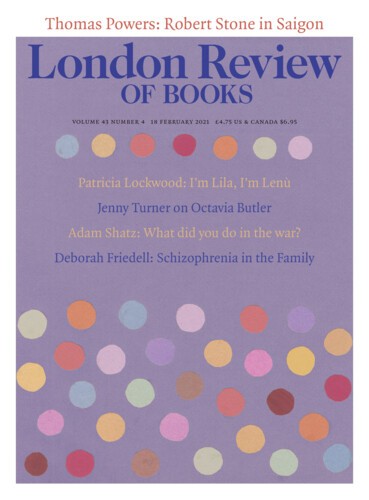

Listen to Raphaëlle Branche talk to Adam Shatz on the LRB Podcast

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.