In the insistent and repetitive rhythm of lockdown, one month melts into another, but the monotony is shot through with dread that comes and goes with terrible intensity. The combination of plague-stricken suspension – the new Covidian temporality – and uncertainty about what’s still in store has made me wonder about old forms of timekeeping. Did they serve to make the passing of time more bearable? Did almanacs, with their cycles of the moon and the stars, red letter days and anniversaries, or breviaries and Books of Hours, with their feasts and saints’ days, help distinguish one day from the next more vividly than we manage today with our constant news feeds? The cycle of the year in a prayer book was enlivened not only by vignettes, historiated capitals and grotesque marginalia, but by stories about the individuals who gave their names to each day.

Such calendars helped people know where they were in relation to longer arcs of time than those marked by church bells or the town clock. Were these co-ordinates plotted to prevent the feeling of sameness, this double sense of time being on a loop and also jammed and imploding? Attaching a strange and wonderful story to each day, as Boccaccio’s bubble of narrators do in The Decameron, seems an ingenious use of the imagination to lift the depression and tedium of shielding from plague. In the Fasti, Ovid’s last, unfinished book, the writer of the Metamorphoses set out to collect – and embroider – the stories remembered by the Roman year. He only managed January to June but he was clearly enjoying himself. It used to puzzle me that The Golden Legend, the massive 13th-century repertory of lurid martyrdoms and incredible wonders, as well as later volumes such as Alban Butler’s 18th-century Lives of the Saints, are organised according to their subjects’ name days: the explanation must be that such books are primarily calendars. We tend to think of the stories these volumes tell as evidence of religious beliefs and rituals, but, as Walter Benjamin points out in ‘The Storyteller’, when men and women are imprisoned in repetitive tasks, storytelling flourishes. He deplored the rise of information in modern times. ‘If the art of storytelling has become rare,’ he wrote, ‘the dissemination of information has had a decisive share in this state of affairs.’ As news outlets pile on updates that feel futile, maybe resorting to outlandish, impossible – unverifiable – stories offers a way out of terminal ennui.

The saints and their wild doings, the angels and their extraordinary powers, now mischievously recorded by Eliot Weinberger, may have helped enliven the days assigned to them. The strangeness of such religious material again and again makes it incomprehensible that such figures should be considered holy, but if you look instead at their adventures as a remedy for the drudgery, dreariness and sheer misery of the daily grind, they take on another significance, as an extreme fiction, an offshoot of the fantastic.

Weinberger’s Muhammad (2006) assembled a life of the Prophet by stitching together passages of his sayings, the Hadith, and creating – without inventing a word – a glorious, startling tapestry of the marvellous. He’s a storyteller after Benjamin’s heart, and has no truck with functionalist explanations; he relishes the unverifiable and offers no rhyme or reason for what he is passing on. He doesn’t claim that saints’ stories help keep track of time or indeed that they have any purpose at all. His distinctive poetic method, in his celebrated essay-poems such as ‘What I Heard about Iraq’ (published in the LRB of 3 February 2005) and ‘The American Virus’ (4 June 2020), is montage, but it has something in common with the cento form, in which a poem emerges from a collage of quotations, each of them unchanged in itself, but profoundly altered by the compiler’s selection, the harmony and dissonance produced by the repetitions and sequencing. This approach comes close to that of a quick-eared anthologist, like Angela Carter in her Book of Fairy Tales, where she manages to give fresh meanings to stale misogynist topoi simply by framing and grouping the tales under subheadings such as ‘Good Girls and Where It Gets Them’ and ‘Strong Minds and Low Cunning’. Angels & Saints offers a variation on this method, as Weinberger mixes his ingredients to bring out their qualities by juxtaposition.

The miscellany begins with an essay on the characteristics of the angelic body and the angelic mind. Weinberger reads Aquinas, who decided that angels ‘assumed’ bodies in order to appear to mortals: these bodies were not ‘naturally united with them’, since angels are ‘beings made of air’ and ‘ethereal beings presumably cannot have any physical or sensory organs.’ (Milton, much later, would nevertheless boldly imagine them having blissful sex.) When angels speak, Weinberger explains, ‘just as they condense the air to become visible, they condense the air to create sounds … it remained debatable whether the angels are speaking on their own, or whether God is speaking through them – in our terms, whether they are cognisant individuals or radios.’ The effect is hilarious at times, but also puzzling and captivating: the gymnastics of human thought can be as spectacular as the art of a Simone Biles. Such displays of intellectual ingenuity were denounced during the Reformation as specious. But it remained a problem for Protestant thinkers that the Bible features so many angels and that their messages are so significant: two bring Lot and his family safely out of Sodom before destroying the city; in the New Testament, Gabriel appears to Mary to tell her she will become the mother of God and another, unnamed angel forewarns Joseph about the Massacre of the Innocents.

Many angels are also famous saints. The town of Saint-Raphaël lies close to Saint-Tropez, but the two resorts’ patrons belong to different orders of heavenly being (Raphael is an archangel; according to legend, St Torpes of Pisa was a bodyguard of the Emperor Nero, and martyred after he was converted to Christianity by St Paul). St Michael is the best-known archangel, and in his role as destroyer of devils is often portrayed in a terrific suit of armour. He is the patron saint of soldiers and police; his shrine on Monte Gargano in southern Italy remembers his support for the Normans as they swept triumphantly eastwards across the Mediterranean to the Holy Land. He became a favourite in Latin America, carried by conquistadors and missionaries, and he appeared in images by local artists with a legion of fellow angels in support, wearing bright feathers in broad-brimmed hats as well as highly wrought cuirasses and greaves (Campion Hall in Oxford has a splendid set of these paintings, rare in Europe). Jehovah’s Witnesses, we are told, believe that Michael is the ‘non-incarnate’ Jesus before and after his spell on Earth. There are oddments of information like this throughout Weinberger’s book, which are fascinating in themselves, but add to the general perplexity about such beliefs: for example, Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, one of the most imposing churches in Rome, built to a design of Michelangelo’s in the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian, was founded to honour a now forgotten vision that in 1460 a certain Amadeus of Portugal received in a cave outside Rome. There the Archangel Gabriel revealed to him that the last Emperor would soon unite the world, ‘an angelic pope’ would be appointed and life on earth would end.

A detour into occult primers discusses angelic mysteries from Dionysius the Areopagite’s Celestial Hierarchy, a Neoplatonist meditation, and The Ladder of Divine Ascent, compiled by the Byzantine monk John Climacus, who lived on Mount Sinai in the seventh century. From the latter Weinberger offers one-liners of absurdist wisdom, echoing Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell but nothing like as sublime: ‘Snow cannot burst into flames’; ‘Waves never leave the sea’; and the oddly timely ‘A man who has heard himself sentenced to death will not worry about the way theatres are run.’

Weinberger describes many visions of angels: St Teresa of Avila’s assailant during her ecstasy may have been a cherub or a seraph (however, seraphs are elsewhere described as snakes). The cherubim are even more elusive to description, having different numbers of hands and feet and wings in the various sources, and ‘eyes “all around as well as inside”, which is difficult to visualise’. Weinberger mentions their transformation into putti, those ubiquitous flying baby erotes of religious Renaissance art, but doesn’t attempt an explanation of this development.

Guardian angels enter the story rather late, but grow quickly in attentiveness and popularity. Christopher Smart trusted that ‘my Angel is always ready at a pinch to help me out and to keep me up.’ They could give domestic help: Gemma Galgani, who died in 1903, was brought coffee by her guardian angel when she was ill, which she frequently was. Pope John XXIII relied on his to negotiate with the angel of a tricky petitioner and sort the problem out in heaven. Guardian angels were also a prominent feature of my childhood: my friends and I would try to catch a glimpse of them at our sides, by turning our heads suddenly in the hope they wouldn’t move out of sight fast enough.

Weinberger follows this comedy with a far more serious, metaphysical passage, a long poem every bit as wonderstruck and worshipful as John Dee and Edward Kelley when they scried their obsidian mirror, seeking to speak with angels. It begins, ‘Angels hovering all round,’ and then scatters, across nine pages, verses like fluttering cherubim, invocations to each of them:

Heiglot,

The angel of snowstorms;Teiazel,

guardian of librarians;Poteh,

The angel of forgetting;

And so on, in a fanciful, wickedly inventive and poignant conjuration. These angels’ names are, I think, mostly made up, though they seem etymologically sound. The litany closes:

Birgitta of Sweden said:

‘If we saw an angel clearly, we should die of pleasure.’

For all the stylish whimsy of this bizarre catalogue, its compiler can’t help but be seduced. Wallace Stevens’s enigmatic half-seen ‘necessary angel’ has eclipsed the Voltairean wag, and Weinberger has slipped back into the poetic calling.

This contemporary breviary moves on to saints, who, unlike angels, have personalities and biographies of remarkable singularity. The subjects range from the familiar to the unknown, and in date from Thecla, Paul’s disciple in the first century, to modern exemplars such as Thérèse of Lisieux, whose relics were taken into space and back, and continue to tour the world, as well as Edvige Carboni, who was declared venerable in 2018. She had interceded for Mussolini to be released from the fires of Purgatory – and was proud when Jesus told her that the prayers had succeeded. The saints are classified in Borgesian fashion under subheadings: ‘Hyacinths’ lists no fewer than 11 saints from the second to the 20th century called after the beautiful youth whom Apollo loved – his death and metamorphosis into a flower became a ‘Christian symbol of rebirth’. Other categories include ‘Weddings’, ‘Dogs and Cats and Mice’ and later, ‘Dogs and Cats and a Trout’ (called Antonella).

The tales take the form of ‘Brief Lives’, giving glimpses of heroic suffering and describing many extreme, often lurid miracles, resurrections, episodes of bilocation, healings, mostly recounted with laconic dryness. Some scenes resemble famous fairy tales: patient Griseldas, wronged queens and Snow Whites persecuted by wicked stepmothers turn up in the lives of several saints. Saint Ailbe of Emly (Irish, sixth century) ‘could turn a cloud into a hundred horses’. St Teilo (Welsh, also sixth century) obligingly produced three corpses when three institutions he founded wanted his relics. Wilgefortis, or Liberata, miraculously sprouted a beard to see off unwanted suitors; she became, as her English name ‘Uncumber’ suggests, the saint who, Thomas More complained, would help deliver women from their husbands. A greyhound, wandering in from an ancient Eastern folk tale about a dog who saves a baby from a snake, inspires an active cult in France as St Guinefort, patron saint for the protection of children. Many sainted characters dream of bliss: Robert Browne, an 18th-century astronomer, of the young Jesus getting into bed with him; St Catherine of Siena of marrying Jesus, who gives her his foreskin for a ring (the lack of self-awareness among our pre-Freudian forebears is prelapsarian; these nocturnal experiences held no shame). Magdalena of the Cross jerks in satanic couplings with a devil called Balban, who is exorcised from her body and exits in the form of a caterpillar ‘with a loud wind … before repossessing her with unprecedented vigour’. Metaphors turn into beguiling reality: after her death three pearls are found in the heart of Margaret of Città di Castello (margaritēs means ‘pearl’ in Greek). Pithy sentences pin down the fate of other saints: of Anthony Grassi we are told that ‘his manner became more serene after he was struck by lightning, which also cured his severe indigestion.’ Philomena, once a much-loved virgin martyr, was one of the casualties of a Vatican clean-up in 1960. One of the nuns at my school was called Sister Philomena, and I remember vividly how distressed she became when the pope announced that her chosen protector was the result of an epigraphic misreading. Some weird favourites are missing, but then saints are almost as numberless as angels. Adding to Weinberger’s inventory is part of the pleasure of this book: what about Gwenn aux Trois Mamelles, for instance, a Breton saint, to whom, on the birth of her triplets, God gave a third breast; or Raymond Nonnatus (died 1240), who worked along the Barbary Coast freeing (Christian) slaves and who appears in his iconography with his lips padlocked together, and is consequently the patron of priests under the seal of the confessional?

Angels & Saints must have been in the making before the pandemic, and protectors from plague aren’t singled out, though they are numerous and beloved all over the world and have inspired some glorious monuments: La Salute in Venice, the magnificent church across the Grand Canal from St Mark’s which is one of the city’s defining landmarks, was built to thank Our Lady of Health for the end of the plague of 1630-31. Santa Rosalia, the patron saint of Palermo, delivered that city a few years before in 1624-25; she was processed through the streets last year in the hope she would defend it again, against Covid-19. St Roch, usually depicted exposing the plague sore on his thigh, was saved by his dog, which brought him food and healed his lesions, and always appears at his side in statues and images. St Edmund the Martyr, whose shrine at Bury St Edmunds inspired a fabulously rich pilgrimage, also enjoyed a cult in France and was credited in the 17th century for lifting the pestilence which had struck the city of Toulouse. He’s now a rather forgotten ‘curer saint’, as the local balladeer Adrian May described him in a carol asking for his help against the virus.

Hagiography and myths share a narrative feature that’s essentially a mnemonic: St Roch has a dog and a sore, just as Hera/Juno has a peacock or Hermes/Mercury has wings on his sandals and helmet. St Apollonia, patron saint of dentists, holds a tooth in a pair of pincers, in memory of the way she was martyred; St Laurence, burned to death on a gridiron, carries a grill (he is the patron saint of cooks – and, less obviously, comedians). But it’s central to Weinberger’s method of estrangement that he strips away function and context: questions about psychology and gender, or shifting attitudes to madness, or the function of sacred figures as helpers and healers, hold little interest for him.

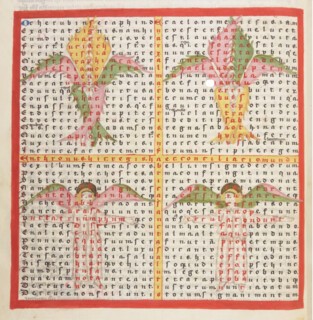

The whole scrapbook is interleaved with sumptuous reproductions of the acrostic prayers devised by Hrabanus Maurus in the ninth century. He was a Carolingian savant who devised complex patterns based on the number 28 (a perfect number, its factors – 1, 2, 4, 7 and 14 – add up to 28). Intricate, gilded, abstract illuminations, these chequerboards are beautiful to look at. Magical devices often depend on near impossible complexity, and these squares resemble the ones on Sufi talismanic shirts, densely written amulets worn to fend off evil djinn. (In Muhammad, Weinberger relates that Amina, the Prophet’s mother, had a series of visions during his infancy; in one of these the heavenly visitant ‘gave the baby a shirt to protect him from the calamities of the world’.) Hrabanus’s intention is not primarily to defend against danger, but to worship: when deciphered, his puzzles offer words of praise and devotion to the Cross. In a lucid afterword, the medievalist Mary Wellesley untangles their meaning and composition, but neither Weinberger nor she explains their inclusion. We may speculate on the way Hrabanus’s austere metaphysical conundrums and Weinberger’s dandyish, often anecdotal storytelling relate to each other. I think the puzzles are intended to alert us to the artifice and contrivance of Weinberger’s work, its detachment from observed or empirical phenomena, and its fascination with the long history of intellectual efforts at grasping angels, miracles and those who perform and receive wonders. Yet Hrabanus’s relation to the whole remains perplexing.

A shared interest in numerology could be one connection: Weinberger has some fun earlier in the book, when he quotes efforts to compute the numbers of angels and devils. Like the measurements of the ark or the Temple of Solomon, these sums become quite dizzying. A Dutch demonologist called Johann Weyer (interestingly, an enlightened sceptic about accusations of witchcraft) calculated that there were 7,409,127 devils. How he arrived at that number is not explained. Hrabanus’s own number magic would later feed into kabbalistic and occult attempts to imagine the immeasurable: the infinity of God.

In the first Duino elegy, Rilke declares: ‘Every angel is terrible.’ Weinberger quotes Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis describing the poet walking on the steep cliffs below her castle: he ‘paced back and forth, deep in thought … Then all at once, in the midst of his brooding, he halted suddenly, for it seemed to him that in the raging of the storm a voice had called out to him, “Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic orders?”’ – words which became the opening of that elegy. But the scene on the cliffs makes it sound as if the storm is speaking to Rilke as someone who might transmit on behalf of those angels – both as a cognisant individual and a celestial radio. Rilke goes on to ask, in Patrick Bridgwater’s translation:

Oh, to whom can we then

turn in our need? Not to angels or men,

and the knowing animals know

we are not very securely at home

in our interpreted world.

Weinberger has made an infidel’s Book of Hours in an attempt to reinterpret a world that is more alien and insecure by the day, to imagine some things beyond the reach of search engines.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.