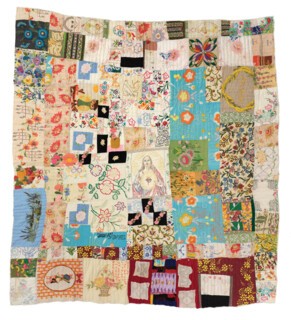

Rosie Lee Tompkins , born Effie Mae Martin in Gould, Arkansas in 1936, grew up picking cotton alongside her fourteen siblings and half-siblings. As was common for a child of rural sharecroppers, her formal schooling was limited, but Tompkins learned to sew by making bedcoverings with her mother, scrapping together any available pieces of cloth. At the age of 22, she joined millions of African Americans who left the South as part of the Great Migration, seeking what Isabel Wilkerson (after Richard Wright) calls ‘the warmth of other suns’. In 1958 she arrived in Richmond, California, a town in the East Bay, north of Oakland and Berkeley, whose thriving Black communities maintained cultural and affective ties to Southern culture through music, religion and food. She enrolled in adult education classes and by the early 1960s was working as a nurse while promoting a burgeoning side venture as a maker of ‘Crazy Quilts and Pillows All Sizes’.

In 1985 Tompkins met the Jewish psychologist-turned-quilt scholar Eli Leon at a flea market. Her story has become inextricably entangled with Leon’s advocacy and promotion of her work. He regularly trawled markets and second-hand stores to amass a large and important collection of more than three thousand Black-made quilts, which he bequeathed to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) on his death in 2018. In the case of Tompkins, Leon’s influence as a patron was outsized: he began actively participating in her process, hiring women to turn her compositions into proper quilts by sewing together fillings and backings – she was unconcerned about standard notions of ‘finish’. He also proposed that she take on a pseudonym that might help her reconcile the demands of an art market hungry for individual authorship with her devout imperative to attribute the inspiration for her designs to God.

The retrospective at BAMPFA, curated by Lawrence Rinder and Elaine Y. Yau (closed until February but available online), features some seventy objects by Tompkins, most of them hung vertically against white walls like tapestries or modernist paintings. It is a studiously dignified presentation that highlights the striking optical effects of her works, as in the showstopper String (1985) with its luscious, undulating strips of velvet and velveteen. The piece (backed in chenille and quilted by Willia Ette Graham) radiates with Tompkins’s energetic use of colour. Reds and maroons and purples and lavenders cascade down the surface in long curving lines. Alternating black strips modulate the rich tones like a steady percussive beat. Tompkins used a vast array of fibres and fabrics, many of them thrifted or found: crocheted doilies, mass-produced crewel embroidery kits, faux fur, terrycloth, linen, cotton feedsack, velour, satin, metallic cord, wool tweed, silk and much else. But her works with velvet and velveteen, for which she had a special affinity, are her most dynamic and impressive.

Velvet, with its short, dense pile of cut woven threads, absorbs light and generates highly saturated colours; it gives an extraordinary depth to Tompkins’s sophisticated compositions. Geometry as an overall structure comes in and out of focus: her improvisational patchwork sometimes cites familiar quilt patterns but never adheres to them. Her grids shimmy out of alignment, and she balances her designs within the borders of her wonky rectangles without ever submitting to the logic of symmetry. Cinched fabric yo-yos spin freely alongside zigzags of embroidered scripture. Some of her quilts integrate imagery from factory-printed children’s sheets, dishtowels and tourist T-shirts to create fractured but suggestive narratives: one, from around 1996, constellates Magic Johnson, O.J. Simpson, Michael Jordan, Nelson Mandela, Malcolm X and others in a fraught tribute to Black masculinity.

Tompkins’s work is attuned to all the nuances of race, gender and class that fabric can signify. When set next to each other to accentuate textural contrast, seemingly similar scraps of cloth are revealed to be relatively luxurious or relatively cheap. A clever all-denim piece that keeps intact the brand names emblazoned on jean pockets (Gloria Vanderbilt, Jordache, Levi-Strauss) – a disorienting rebus-like surface – registers the differing prestige afforded to identical material. Synthetic calico is set next to a Mexican serape poncho which is placed next to an Indian scarf: these are inventories of the way we live our lives awash with textiles, alert to ideas of status, identity, waste and reuse.

Though Tompkins, who died in 2006, has been featured in a number of small solo shows and group exhibitions, including the 2002 Whitney Biennial, the BAMPFA exhibition is the largest selection of her work so far assembled. Her aesthetic project is certainly worthy of this attention, but she also produced a range of interesting usable objects – including the ‘pillows of all sizes’ – that are not on display here. Of course, her quilts decisively blur such distinctions, but the installation at BAMPFA betrays an anxiety about the way audiences may understand this work, or misunderstand it. Works by non-professional makers – sometimes called ‘self-taught’, ‘outsider’ or ‘outlier’ – have been making their way into art institutions for some time, but Black women artists who work with textiles are still far less likely to be celebrated for their artistry than for their technical skills. The show’s fine-art framing positions her practice as more art than craft, removing the quilts from their possible inclusion alongside her other creations in more domestic settings.

The one exception to the exhibition’s wall-based display is a small arrangement of assemblage sculptures, encrusted with costume jewellery, glue caps and ribbon rosettes, showcasing Tompkins’s humour as well as her indebtedness to African diasporic folk rituals. The Middle Passage lies somewhere behind the many echoes of African textile traditions in her work. Attempting to give shape to the slave trade, Édouard Glissant wrote: ‘It might be drawn like this:  African countries to the East; the lands of America to the West. This creature is in the image of a fibril.’ Glissant imagined the connection between Africa and the Americas as a textile thread, and the exhibition opens up suggestive possibilities about the intertwining of a range of Black female material practices, aligning US artists such as Tompkins, Faith Ringgold and Sonya Clark with Afro-Brazilian artists such as Sonia Gomes and Rosana Paulino. Their diverse practices with fabric and thread point to mending as a powerful metaphor: these works stitch together new Afro-Atlantic histories and suture narratives that had been ripped apart.

African countries to the East; the lands of America to the West. This creature is in the image of a fibril.’ Glissant imagined the connection between Africa and the Americas as a textile thread, and the exhibition opens up suggestive possibilities about the intertwining of a range of Black female material practices, aligning US artists such as Tompkins, Faith Ringgold and Sonya Clark with Afro-Brazilian artists such as Sonia Gomes and Rosana Paulino. Their diverse practices with fabric and thread point to mending as a powerful metaphor: these works stitch together new Afro-Atlantic histories and suture narratives that had been ripped apart.

There is an echo of slavery’s violent erasure of names in Eli Leon’s renaming of Effie Mae. His practice of collecting underpriced quilts could be seen as extractive or exploitative – such charges have been levied at the white art dealer William Arnatt, who claimed to have ‘discovered’ the Gee’s Bend quilters – but Horace Ballard, in his contribution to the exhibition catalogue, perceptively suggests that ‘Rosie Lee Tompkins’ might be best understood as a placeholder that gestures to all those who worked on a given object, since many of the pieces on display were brought into being by collective labour – not to mention divine inspiration.

Tompkins’s religion is central to her work: conjoining text and textile, she frequently stitched Bible quotes on her surfaces and the cross is a repeated compositional element. This is a moment of reckoning for the secular bias that has held sway over so much 20th and 21st-century art history: religion can’t be so easily dismissed. Tompkins saw her own ingenuity as shining forth from the replenishing resource of Seventh-day Adventism, and her piecing and stitching were small acts of prayer-like devotion. Jesus’ face reappears in several of her works, including in a piece from the 1970s that incorporates a popular sacred heart embroidery template, complete with blonde hair and blue eyes. Her capacious recycling of familiar commercial imagery is a reminder that Tompkins has her place not just in textile history and the history of modern art but also in the specific lineage of art appropriation that includes the work of Beatriz González and Glenn Ligon.

Tompkins was a skilled technician as well as a material innovator. Some of her pieces are quite small and others monumental, but all convey the intimacy of handiwork, often evident in the tufts of yarn protruding from rippling cloth surfaces. I saw the exhibition twice: once during the exciting welter of activity around its opening in February, and then again, more cautiously, as the sole visitor granted permission to enter the pandemic-shuttered museum a few months ago. On my second visit, I was struck by the correspondences between Tompkins’s textile-based improvisations and an encampment of tents on the street outside that had been augmented and personalised through inventive uses of scavenged materials. Though they offered inadequate protection from the smoke of nearby wildfires, the makeshift shelters – clustered together in the face of a virus that has exacerbated already raging economic inequalities in northern California – are connected to Tompkins’s work, and other forms of Black making, with a fragile but unbroken fibril.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.