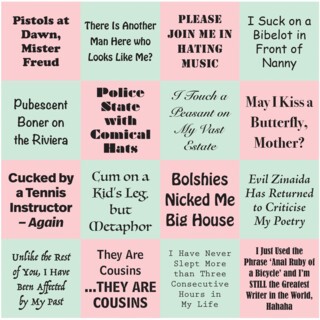

Strong Opinions , a collection of Nabokov’s interviews, reviews and essays published in 1973, contains an interview with the great man so brazenly bad, so shocking in each successive clause, that as long as you’re reading it, you’re dreaming of the movie version. Picture Benedict Cumberbatch hunched over a legal pad, sweating lightly, pressing Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (Jared Harris) to admit that a sentence about a character paring his fingernails was inspired by James Joyce. Admit it he does not: ‘The phrase you quote is an unpleasant coincidence.’ Cumberbatch’s sweating intensifies. His jumper has been nibbled by the only moths on earth that are beneath his idol’s notice. Vladimir toys sardonically with the rook on his chessboard as Véra (Tilda Swinton, wearing the whitest wig money can buy) brings in a tray. ‘Are you aware that I saved Lolita from the incinerator?’ she asks, as she pours the tea. It is her only line.

In this new collection of ephemera, Think, Write, Speak, Nabokov identifies that industrious interviewer, Alfred Appel, Jr, as ‘my pedant … Every writer should have such a pedant. He was a student of mine at Cornell and later he married a girl I’d taught at another time, and I understand that I was their first shared passion.’ Imagine it: erotic unification over this man, someone who hated music in public places, fascists and Bolshevists, the feel of satin; who was dolphin-like in his movements, an obsessive self-googler before easy engines existed, who could not spell ‘tongue’ correctly on the first try. Every writer should have such a pedant – every writer should have two, returning in the evenings to commune over the crucial works, the neglected fragments. Perhaps, on some hardly-to-be-hoped-for day, discovering themselves brother and sister.

A complete biography lurks behind the slow accumulation of these pages. We begin, what could be more boyish, with descriptions of the ‘wild dark-grey trousers’ of Cambridge, with paeans to Rupert Brooke, with bubbling appreciations of not very good poetry. He is an émigré, and unmistakeably happy to be at work building his name: this happiness is what finally convinces us that he truly didn’t miss all that White Russian money, gone up to heaven like vapour. Gradually he becomes famous, and is persecuted with so many questions about nymphets and Freud that some essential openness closes, the openness you see in the early letters to Edmund Wilson, in the avalanche of epithets he piles on Véra during her stay in a sanatorium before they were married. From the comfortable vantage of a Swiss eyrie, the myths and just-so stories are launched and refined. ‘What have you learned from Joyce?’ ‘Nothing.’ ‘Gogol?’ ‘I was careful not to learn anything from him.’ If Nabokov and I have one thing in common, it’s that we were both careful not to learn anything from Gogol.

In this book a soft, damp skin hardens into a polished and uncrushable carapace – reminiscent of those palmetto bugs I used to smash with a Bible in my apartment in Florida, which could be flattened to the thinness of a dime and still live. On the first page, he is enthusiastic, deferential, eager; by the last he is a triple-reinforced roach that cannot be killed. He isn’t a regular roach, though. He’s an Art Roach. He buffs and buffs himself, until the Alps outside the window are reflected in his own high shine, and entering from stage left, we see the shape of Véra.

After 1958, Think, Write, Speak contains little except interviews; when an answer sounds like an echo in a marble hall, it is because he has repurposed it from Speak, Memory. The sameness is unrelieved – until the late 1960s, when various malpractising journalists begin asking him about hippies, which is pleasant. (‘I feel nothing but contemptuous pity for the illiterate drug-dazed hoodlums I have happened to observe, but I do not assume that all hippies are violent cretins.’) We end with the hilarious statement, the fitting and most Nabokovian lie: ‘If I do have any obsessions I’m careful not to reveal them in fictional form.’

There is a static quality to Nabokov’s earliest reminiscences. The rooms of his childhood are presented as chessboards, waiting for the mysterious animating force of the game. ‘I see again my schoolroom in Vyra,’ he writes in Speak, Memory,

the blue roses of the wallpaper, the open window. Its reflection fills the oval mirror above the leathern couch where my uncle sits, gloating over a tattered book. A sense of security, of wellbeing, of summer warmth pervades my memory. That robust reality makes a ghost of the present. The mirror brims with brightness; a bumblebee has entered the room and bumps against the ceiling. Everything is as it should be, nothing will ever change, nobody will ever die.

I would remember this childhood too; we all would. It takes place in a paperweight. ‘A coloured spiral in a small ball of glass, this is how I see my own life.’ A young aristocrat, 75 per cent composed of foraged mushrooms, asks his pristine parents what an erection is, and they tell him that Tolstoy has died. Who can’t relate? But while these early impressions are documented photographically, his young adulthood is less thoroughly treated. The world, which previously creaked on its axis, has begun to gather speed. He is expelled from his nursery, a staggering inheritance from that gay leathern uncle is won and lost in what seems only a day, his father is assassinated while attempting to shield the real target. But the elision of these years has less to do with memory and more to do with the fact that to be young and unformed is embarrassing to such a man; to see the sun of your encompassing power on the horizon, but not to be able to grasp it, or even to look at it directly. In the earliest essays, we see species, categories, periodic tables; languages and countries; real and alternate histories are set before him and we see him reach out a hand towards what he is, what he is going to be. Anything is possible. His mother has been all morning in the woods and parks of St Petersburg; she lets the bounty of him fall to the floor with an exaggerated pouf!

Perhaps this is why Chapter 15 of Glory glows so among his writings. It is where he chooses, and his doppelgängers choose – even though, as he states in the preface to the later English edition, he was careful to give the protagonist No Talent. The temptation to do so must have been strong, for a man whose eyes were constructed like Aladdin’s to see dazzle in the dark. The rubies move: they are better, they are beetles.

When he entered the university it took Martin a long time to decide on a field of study. There were so many, and all were fascinating. He procrastinated on their outskirts, finding everywhere the same magical spring of vital elixir. He was excited by the viaduct suspended over an alpine precipice, by steel come to life, by the divine exactitude of calculation. He understood that impressionable archaeologist who, after having cleared the path to as yet unknown tombs and treasures, knocked on the door before entering, and, once inside, fainted with emotion. Beauty dwells in the light and stillness of laboratories: like an expert diver gliding through the water with open eyes, the biologist gazes with relaxed eyelids into the microscope’s depths, and his neck and forehead slowly begin to flush, and, tearing himself away from the eyepiece, he says, ‘That settles everything.’

After reading that I always feel a whoosh, as if I’d just stepped back from the edge of a cliff. We almost lost him to the study of viaducts. Instead, he chose literature, the only dark capable of containing all that array, as well as occasional detours into ‘the classification of certain small blue butterflies on the basis of their male genitalic structure’. Well, obviously.

Erudition is delicate to dissect. It is one of the little creatures that has learned to look like other things: bark and background, eyes. His seems as if it must have developed over uncountable years, but that is not so – we witness him learn, in these early essays, to lay his pattern precisely on a sheet of paper. To read them is to be inside his desk, in a snow of notes, among the worldly flurry of what drew his attention. We mark the sharpening of his little knife: ‘The author pretends to be an idiot, but why isn’t clear,’ he writes in ‘A Few Words on the Wretchedness of Soviet Fiction’. ‘I shall limit myself to an excerpt. Here it goes: she leaves, he immerses himself in party work. And the story ends like this: ‘“Goddammit,” he said, “we have huge economic opportunities.”’ We follow his excursions into nostalgia: ‘At a fair, in a remote little town, I won a cheap porcelain pig at target shooting. I abandoned it on the shelf at the hotel when I left town. And in doing so, I condemned myself to remember it. I am hopelessly in love with this porcelain pig.’ And we receive his unchanging thesis: ‘Though I personally would be satisfied to spend the whole of eternity gazing at a blue hill or a butterfly, I would feel the poorer if I accepted the idea of there not existing still more vivid means of knowing butterflies and hills.’

The day is visible somehow in these interviews, slanting down through tall windows, and I found myself thinking very often of what he had for lunch, perhaps because of those cutlets and compotes so frequently described in the early letters where he calls Véra ‘Pussykins’ and ‘Tufty’. To read the interviews is to see the whirlwind of index cards, the dry white fountain, the dead leaves of his prepared answers and the breeze of his off-guard ones. He is most alive in an interview with Sports Illustrated about butterflies. ‘Chort!’ he exclaims. ‘I have been doing this since I was five or six, and I find myself using the same Russian swear words. Chort means “the devil”. It’s a word I never use otherwise.’ He looks at the landscape and says: ‘It looks like a giant chess game is being played around us.’ (Everything is as it should be, nothing will ever change, nobody will ever die.) While Véra shops in the supermarket, he tells the interviewer that

when I was younger I ate some butterflies in Vermont to see if they were poisonous. I didn’t see any difference between a Monarch butterfly and a Viceroy. The taste of both was vile, but I had no ill effects. They tasted like almonds and perhaps a green cheese combination. I ate them raw. I held one in one hot little hand and one in the other. Will you eat some with me tomorrow for breakfast?

Where is the butterfly-eater, exuberant and mad in the manner of a ten-year-old naturalist, absorbed in a particle that looks like the world, in the rest of these ossified answers? And what is Véra buying in the supermarket – almonds? Green cheese?

I am not one of his pedants, yet I thought of them often as I reread his work. Nabokov and I are hardly a match made in heaven – I’m stumped by the most elementary brainteasers, every chess game I’ve ever played has lasted at least two hours and no one has been able to win, and when faced with a fictional family tree, I feel I’m trying to eat a Filofax. Still I revisit him: Speak, Memory, Lolita, my beloved Pnin, Pale Fire.

Pale Fire is a book that could be read for an entire lifetime, always on the verge of discovery, until finally, at the end, it shows up: a bigger, more respectable, more transcendental version of the assassin Gradus, walking towards the staggered flash of a million photographers. It has no solution because it is designed to work like human memory: returning obsessively to a secret passageway discovered in childhood, flight over a spine of mountains (read with the brain, the backbone, the little hairs), the hiding place of the crown jewels. The index is in the body – one reference will send us chasing after another, and the same scarlet pages crop up again and again on a darkness that is the inside of the eyelids.

Yet none of this highfaluting language conveys my bug-eyed discomfort when I actually read Pale Fire, clawing dutifully after every footnote, stuffing the commentary with post-its, triple-underlining phrases like ‘his brown shoes’, only pausing occasionally to see the white fountain of remixed and continuous life that John Shade saw when his heart stopped. Nabokov sets up problems to which it seems there should be answers, but he does not give answers, he gives rewards. That is why he is beloved, why people dedicate whole academic lives to him. White fountains at the end of the mind.

What is it about, except the foolish human feeling that literature is written directly to us, that it is a letter with an imperishable blank in the address? ‘I was holding all Zembla pressed to my heart.’ We are Kinbote tiptoeing across the lawn, holding the rubber-banded batches of index cards against our chest. We have chased down every lead, hunted down all the echoes, put ourselves in possession of the ultimate meaning. We have made a grand discovery: the story is about us. We will spirit it away, and fill in every blank with our own name.

Some of this shit is for chess people; he is a Sherlock Holmes who pops clues into his mouth for the sheer oral sensation. (It is appropriate, both in terms of his work and his profile, to think of him as an Alfred Hitchcock who insists on appearing in every frame of his movies, not just a single scene.) But how beautifully he speaks of it! ‘There is no time on the chessboard. Time replaced by a bottomless space,’ he said in one interview. ‘The knight jumps a square. But if, for example, it is at one side of the chessboard, then one wonders why it can’t jump from the other side, in the space beyond the chessboard. I have myself thought up problems which incorporate the possibility of a knight who flies off and then who comes back from that space.’ The knight is a character, the space is fiction, the flying off and the landing again is the work. ‘I suppose I am especially susceptible to the magic of games,’ Humbert confesses in Lolita. ‘In my chess sessions with Gaston I saw the board as a square pool of limpid water with rare shells and stratagems rosily visible upon the smooth tessellated bottom, which to my confused adversary was all ooze and squid-cloud.’ Conceptions of space, dimension, movement, strategy. Some of the books move on highways; some down corridors; some through wormholes; some sit stationary in the darkness of cinemas. Some go to college, where sometimes he is the student, slicing across the quad, and eventually the professor, patting his suit pocket for his notes: did he leave them on the train again? Chort!

Something curious and wonderful happens when you read his lectures: you slip into the flow and the logic of his reading. Towards the middle of them – as he is musing on a sentence from Dickens, say, which the word ‘heavy’ properly weights down – no one else is there. Certainly, there are no students, no Thomas Pynchons, no Ruth Bader Ginsburgs. The word Eigengrau means own grey, or intrinsic grey, or brain grey. It is what you see when you close your eyes. After a while you are in Nabokov’s own grey, turning down corridors, coming on the characters in their humble rooms, which are still inflected with the grandness of his childhood ones, they cannot help it. High ceilings, a patch of dazzling snow outside the window, a paperweight winking on the mantlepiece. I haven’t even read Bleak House – it is the cherished prerogative of an uneducated person, to save Bleak House for the end of the world – yet there I was, a little thread between my fingertips, following his dolphinish walk through the fog, and entering the place where Krook has spontaneously combusted.

In his lecture on Jane Austen, Nabokov uses the term ‘knight’s move’ to describe how Austen manoeuvres her characters from one side of the board to the other, emotionally. (The concept is invoked here too, less flatteringly, in a review of Hilaire Belloc.) ‘Fanny’s relief, and her consciousness of it, were quite equal to her cousins’, but a more tender nature suggested that her feelings were ungrateful, and [knight’s move] she really grieved because she could not grieve.’ What he himself does, then, might be called a queen’s move. If his protagonists are often cornered like the king, it is the language that rises up and flies diagonally across the board.

Consider the sentences we see particularly in Pnin, which collapse all distance in the final clause. ‘Dr Falternfels was writing and smiling; his sandwich was half-unwrapped; his dog was dead.’ Consider Humbert, making the leap off the board into the air:

All I know is that while the Haze woman and I went down the steps into the breathless garden, my knees were like reflections of knees in rippling water, and my lips were like sand, and –

‘That was my Lo,’ she said, ‘and these are my lilies.’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘yes. They are beautiful, beautiful, beautiful!’

‘Are you a pervert, sir?’ goes one prominent line of questioning. In the absence of a cache of erotic letters about, say, a desire to frot schoolgirls on trains, a compulsion to cum into butterfly nets, the answer seems to have settled on ‘no’, with a certain amount of disappointment: in a century that stood in the shadow of Freud, there is no richer text than a pervert. No matter how buttoned up a biographer might be, it is his secret wish to discover that a writer is in possession of a hideous Phalloides that can flourish only in damp darkness. Instead, we have Pussykins and Tufty, descriptions of compotes, hopeless love for lost porcelain pigs.

‘It’s a very tender book,’ Nabokov insists, in an interview with L’Express. ‘An American map of tenderness.’ If you read Lolita as a young girl, you feel clearly, colourfully, photographically seen – someone is paying attention to the little tendon twitching at the side of your ankle! ‘The thousand eyes wide open in my eyed blood.’ I know many women of my generation who bear a half-shamed attachment to it, for the same reason many of them love Léon; the girl still nominally the focus. It is easy – it seemed easy to me, when I was a teenager – to discard the surrounding pervert, and simply keep his eye.

If Lolita is in many ways the most accessible of Nabokov’s novels, it is because it places the labyrinth outside, in the sunlight. After all, most people who read Lolita in a swoon of desire don’t want to fuck a child, they want to go on a road trip, and read Burma Shave billboards out loud from the passenger seat. It is a commonplace by now that Lolita is the greatest novel ever written not about love, but about advertising. Nubile red-lipsticked America – revealed at the crucial moment to be already corrupt – is fondled by the hoary hand of Europe! The war is over, the country’s right pocket is unaccountably deep, the road into the future has just been repaved. ‘And I catch myself thinking today that our long journey had only defiled with a sinuous trail of slime the lovely, trustful, dreamy, enormous country that by then, in retrospect, was no more to us than a collection of dog-eared maps, ruined tour books, old tyres, and her sobs in the night – every night, every night – the moment I feigned sleep.’

I am reminded of my father-in-law (no, not like that), who once insisted on staying at a hotel called the Free Breakfast Inn simply because of the promise implicit in its name. All the other hotels also offered free breakfast, but only one of them was the Free Breakfast Inn, and that is what it means to be an American. Nabokov knew this, and seemed to delight in it, as Humbert delighted in Lolita’s banana-split vulgarity. The journey along these highways is designed for us, to keep our childish attention spans engaged so he can keep dallying with us. We stop at all the souvenir stands along the way; our side of the car is littered with movie magazines, empty Coke bottles, candy bar wrappers. We are wearing an outfit picked out and purchased for us: preposterous, gingham-checked, made to our measurements and revealing the midriff. The book is the bonbon produced so we don’t tell, and if further inducements are necessary, the movie will be playing later. Lolita is powered not just by the nostalgia that is but by the nostalgia that will be: Nabokov knows that there will be people in the future who are not just hungry for sandwiches, but want to eat tuna salad on white, at a drugstore counter, in the year 1947. If the child is pathetic for being susceptible to the image, the protagonist is more so – he lives in the belief that the mirage can be reached, that the projector playing footage of a girl directly into his eye will one day set a real cameo in the palm of his hand and he will have her. ‘Distant mountains. Near mountains. More mountains; bluish beauties never attainable, or ever turning into inhabited hill after hill.’

But what about the girl herself? ‘She cries every night,’ Véra pops in to say, ‘and the critics don’t hear her sobs.’ Véra pops in very often to defend Lolita, to underline some point of her husband’s, to deepen her with a real shadow. ‘Did you know I saved her from the incinerator?’ She rescued her once and she must keep rescuing her, for she knows something that her husband does not: Lolita in its second half is something we no longer want.

The road trips were their road trips, after all, to catch butterflies in the American west. The hotel bed in the centre of the book is their bed. If a pair of wings is fixed here, it belongs to them: by the time revenge, imprisonment and old age arrive, they are completely beside the point. In another interview with L’Express, Nabokov called America ‘the country where I’ve breathed most deeply’. It is the sky that travels down to fingertips and toes, surrounding an image which can never be held.

Such glamour accrued to him after Lolita that he is one of those 20th-century writers that readers fear to admit they don’t understand. It should not be so. Unusual minds do not always admit others, and some Pale Fires are not lucky enough to have Mary McCarthy as their first reader. Sometimes he is boring and overdazzled at the same time. Try reading Ada or Ardor with a headache and see if you don’t feel that you’re listening to the heartbeat of an overdosed magician. Try embarking on Bend Sinister – a book that seems to have been born of the trauma of once holding a Nansen passport – with a fever and see if you don’t spend the next few weeks chased by a secret policeman bent on arresting you for the crime of illiteracy. They keep crossing a bridge, it makes no sense. My head feels hot, my brain a bubble being blown by a 12-year-old girl …*

In Pale Fire Kinbote asks, ‘What if we awake one day, all of us, and find ourselves utterly unable to read?’ In Bend Sinister Nabokov speaks of ‘the recurrent dream we all know (finding ourselves in the old classroom, with our homework not done because of our having unwittingly missed ten thousand days of school)’. The books themselves often partake of that dream. Often the narrative slips into the interval just before sleep – you are following, following, and then suddenly your footprints are crossing through snow and carrying you into some grim, bureaucratically deranged, claustrophobic country. This is when it seems most futile to employ a critical lens at all: why are we applying waking standards to what are fundamentally sleepwalking works, stuffed with the jewels of little purple pills?

The problems he sets us are like the problems that Timosha, a conscientious child who will grow up to be a pedantic professor, encounters when he looks at his wallpaper with a head inflated by illness, trying to discern what governs the repeating pattern on his wallpaper:

It stood to reason that if the evil designer – the destroyer of minds, the friend of fever – had concealed the key of the pattern with such monstrous care, that key must be as precious as life itself and, when found, would regain for Timofey Pnin his everyday health, his everyday world; and this lucid – alas, too lucid – thought forced him to persevere in the struggle.

In Speak, Memory, we visit the original sickbed: ‘My numerous childhood illnesses brought my mother and me still closer together. As a little boy, I showed an abnormal aptitude for mathematics, which I completely lost in my singularly talentless youth. This gift played a horrible part in tussles with quinsy or scarlet fever, when I felt enormous spheres and huge numbers swell relentlessly in my aching brain.’

I hate it when my tussles with quinsy rob me of my abnormal aptitude for mathematics. Rather than coming alive when you are delirious, his scenes close – bookcases refuse to revolve at the touch of a button, portraits no longer conceal safes. The mind is overtaken by one panicked question: what the hell are you talking about, dude? It’s very comfortable to read him in full possession of your faculties, and it’s possible that his madcap plots, with their hint of sped-up silent movie footage, never entirely came off because he was so manifestly sane – not a madman, undeluded, not a pervert in the smallest degree. But to read him from inside a balloon, holding a passport that no longer means very much to the outside world, is a different thing altogether. Borders do close overnight, the secret police are once more on the move and you are in bed with a fever. The pedant sometimes steps from the dark of a library, from the daylong light of an interview, into a different world.

I am not his pedant. My insights are more like those of poor Joan Clements, at the party at Pnin’s house: ‘But don’t you think – haw – that what he is trying to do – haw – practically in all his novels – haw – is – haw – to express the fantastic recurrence of certain situations?’ Even so, I was up all night. There I was, cocooned in my blankets, having missed ten thousand days of school, trying desperately to guess where the squirrel would pop up again, the lily pond, the bridle path felted with fallen leaves, the old man (was it him?) hunched up on a bench.

Nabokov gazes at a snowy slope outside the window. He is 65 years old; his nose is perfect. With wrists and palms, like his fictional professor, he outlines a portable world. Benedict Cumberbatch raises his pen once more over his notepad. He has been physically and mentally ruined by this experience and will die soon afterwards. ‘Learn to distinguish banality,’ Nabokov advises him, just before the film fades out. ‘Remember that mediocrity thrives on “ideas”. Beware of the modish message. Ask yourself if the symbol you have detected is not your own footprint. Ignore allegories. By all means place the “how” above the “what” but do not let it be confused with the “so what”. Rely on the sudden erection of your small dorsal hairs.’

This is what he tells us again and again, to read a book with the brain and the spine, the spot between the shoulderblades – to walk back with him to that time of youth, riches, the shining array in the deep dark, and back to the moment when he chose.

Undecided what to undertake, what to select, Martin gradually rejected all that might take a too exclusive hold over him. Still to be considered was literature. Here, too, Martin found intimations of bliss: how thrilling was that humdrum exchange about weather and sport between Horace and Maecenas, or the grief of old Lear, uttering the mannered names of his daughters’ whippets that barked at him! Just as, in the Russian version of the New Testament, Martin enjoyed coming across ‘green grass’ or ‘indigo chiton’, in literature he sought not the general sense, but the unexpected, sunlit clearings, where you can stretch until your joints crunch, and remain entranced.

To travel back to that beginning is to walk with him a very long way, through green grass to sunlit clearings, from the trees of one continent to another. Your passport is this little nut you found. The symbol you have detected is your own footprint. ‘This one is an Angle Wing,’ he says, pointing out something nearly invisible to you. ‘It has a curiously formed letter C. It mimics a chink of light through a dead leaf. Isn’t that wonderful? Isn’t that humorous?’ And then his voice calls happily ahead of you, as if to the world and all the things in it: ‘Charming! Charming! Charming butterfly road!’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.