In the spring of 1972, the poet Bernadette Mayer began to keep a journal for her analyst, David Rubinfine, whose patients included Tuesday Weld and Anthony Perkins, and who was notorious for having married another patient, Elaine May, a decade earlier. Mayer was 27. In the journal – there were two, in fact; Rubinfine read one while she wrote in the other – she attempted to record her states of consciousness. The collected work, a three-year experiment published as Studying Hunger (1975), announced its ambition at the start:

If a human, a writer, could come up with a workable code, or shorthand, for the transcription of every event, every motion, every transition of his or her own mind, & could perform this process of translation on himself … someone could come up with a great piece of language/information.

The possibility of looking at everything had already inspired Mayer’s photo-and-text project Memory. In July 1971 she decided to capture ‘every smallest detail of life, to see how far I could go’, shooting a roll of film each day for a month and obsessively noting down every thought, observation, experience. By the end of the project, Mayer wondered if she was losing her mind. A few months later, she started psychoanalysis with Rubinfine.

Mayer was born in New York in 1945 and endured a strict Catholic education alongside her sister, the sculptor Rosemary Mayer. They were orphaned as teenagers and Mayer became convinced that she would die of a brain haemorrhage at the age of 49, as had members of her father’s family. There was no time to waste. (In the event, Mayer did suffer a brain haemorrhage aged 49, but survived.) She studied at the New School and began teaching poetry workshops at St Mark’s Church, collaborating with Alice Notley, Ted Berrigan, Robert Creeley and others. John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara were their guiding lights. A new American poetics was taking shape: daily and referential, tough and casual. Between 1967 and 1969 Mayer edited, with Vito Acconci, the experimental mimeographed magazine 0 to 9, which combined work by poets and artists – Clark Coolidge, Kenneth Koch, Adrian Piper, Robert Smithson, Yvonne Rainer.

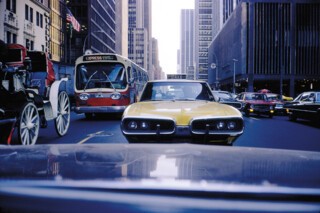

Memory, a ‘conceptual piece lacking conceptual data’, was part of this new wave. By the early 1970s, pure abstraction had given way to works in which artists used themselves as material, and didn’t try to conceal it. Memory was first presented as a multimedia installation at 98 Greene Street in February 1972: 1176 small colour prints were mounted in a large horizontal grid, to be read from left to right, accompanied by a series of audiotapes (totalling more than six hours) of Mayer reading from her journals. She wanted to ‘illustrate what I remembered’ so that the viewer would ‘know what it was to become me’. Barrage was her method. The large scale of the grid and the minute detail of the photographs, combined with the drone of Mayer’s voice, was intended to blur the boundaries between the viewer and the artwork. But the ‘me’ that makes up Memory is fractured and atomised: it’s far from singular.

The project wasn’t shown in its complete form again until 2016, at the Poetry Foundation in Chicago. It has been more frequently exhibited in condensed forms, and the text was published without accompanying photographs in 1975. Now Siglio Press have published a complete edition, interspersing the photographs with her journal entries.* Time was her subject and her constraint, but this was as far as she went in adhering to the established modes of conceptual photography. Her work, technically erratic and highly personal, departed from the deadpan black and white snapshots typical of Sol Lewitt or Ed Ruscha. She was often on the road, travelling in and out of New York, staying with smalltown friends, passing through bars and diners. There are bursts of yellow everywhere. We see New York at a particular moment: the rust on the materials for the World Trade Center, then under construction; a bird’s-eye view of Times Square in mid-afternoon sunlight; firecrackers at the Morton Street Piers. The most arresting images are the shots of Mayer herself. Some days appear as condensed photo-essays (taxi cabs, sunsets, newsstands, parking lots, luminous white clouds), visual counterparts to her riffs on colour and sensation. In Mayer’s photographs, daily life seems less a matter of individual experience than of a generic surface texture, changing slowly over time.

‘There are so many things you never think to do there are so many ways of predicting the time there are ways of remembering it are there more ways of remembering it.’ Mayer’s linguistic experiments, ranging between records of external perceptions and mental images drawn from the past, register disruptions of place as well as different contexts and modes of speaking. The action in her journals, if it can be described as such, registers disruptions of place and context and modes of speaking, producing a sense of continual transition (there is an obvious debt to Gertrude Stein). She switches rapidly between observation – ‘southview south on rte 8 the alternate way the north adams vietnam veterans memorial skating rink flat as a church’ – and playful flips: ‘Dinners I’m supposed to go to dinner I already went I go again & again in long addresses in long dresses, tom, we take acid before a dinner then lose track.’

Then there are her lists:

i’m going my way i’m getting along i’m going on i’m shoving off i’m trotting along i’m staggering along i’m moseying along i’m buzzing off i’m moving off i’m marching away i’m pulling out i’m leaving home i’m going from home i’m exiting i’m breaking away i’m o i’m setting forth i’m retiring i’m going down to the sea i’m removing i’m ceasing to be i’m disappearing i’m vanishing from sight i’m doing the vanishing act

These are juxtaposed with ironic lines that might have been pulled from Twitter: ‘identity floats somewhere between a review of masterplots in the dictionary & the word girlfriend.’ Everything she considers – car rides, dreams, conversations, emotions – is given the same sharp but glancing attention. Over time, the distinction between the external world and her inner life is eroded. Fixed reality seems suddenly beside the point.

The texts of Memory are in two stages. Mayer initially recorded her impressions in real time: it is closer to an almanac than a journal, sharing no secrets, no sex, no shame. A month later she projected the slides and recorded her reactions to what she saw, exploring ‘the idea of myself of the present moment remembering & that of myself of the past moment conceiving’. The two texts are mixed together in the book, so that long, unpunctuated sentences give way suddenly to discursive passages: ‘in a system every fact is connected with every other by some thought-relation & the consequence is that every fact is retained by the combined suggestive power of all the other facts in the system & forgetting is almost impossible.’

Mayer ended her psychoanalysis with Rubinfine in 1975, months before the publication of Memory. Their relationship had been characterised by cat and mouse games, and by his repeated attempts to seduce her. He made one last, ambiguous power play: he asked to write the introduction. It’s a page long and concludes: ‘If Bernadette Mayer has any progenitors they are most probably Proust and Joyce. But she is no mere epigone. Her writing is so original that it seems very much like her own invention. But I had better stop here since I realise suddenly that I am so envious that I am struggling with strongly competitive urges.’ The preface doesn’t appear in the new edition.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.